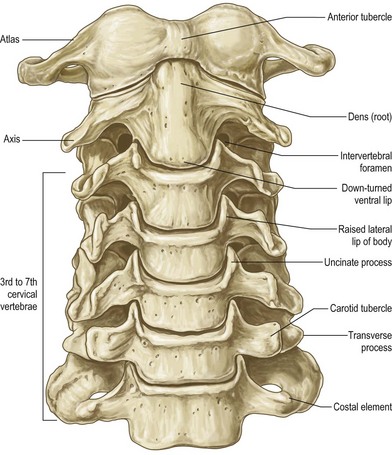

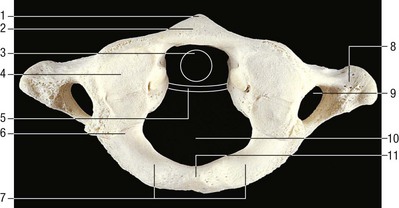

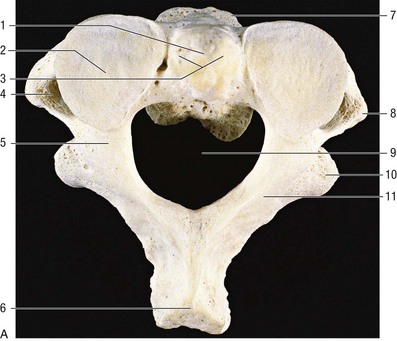

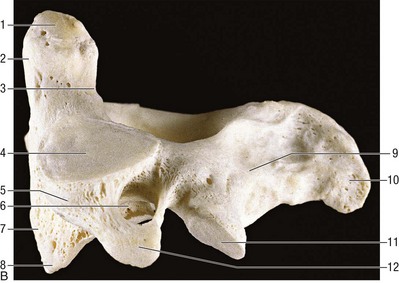

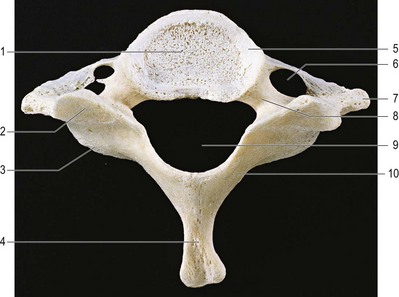

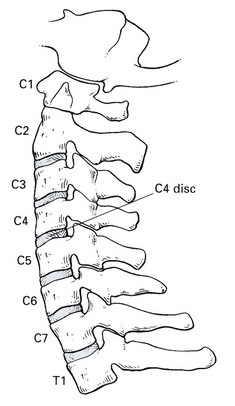

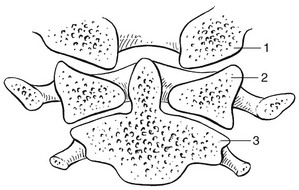

The cervical spine has seven vertebrae, which may be divided into two groups that are distinct both anatomically and functionally: the upper pair (C1 and C2, the atlas and axis) and the lower five (C3–C7) (Fig. 1). The atlas (Fig. 2) does not have a vertebral body – this has been absorbed into the axis vertebra, to form the odontoid process (Fig. 3). A thick anterior arch remains, extending into and joining the two lateral masses, on which are the superior atlantal joint facets, which articulate with the occipital condyles; and the inferior joint facets of the axis. The posterior arch is thinner than the anterior arch and forms the posterior junction of the lateral masses. The large vertebral foramen thus formed has a larger diameter in the transverse than in the sagittal plane. The second cervical vertebra is the axis (Fig. 3). Its vertebral body is formed by fusion with the vertebral body of the atlas to form the odontoid process (or dens), which is completely separate from the atlas. The laminae of the axis are very well developed and blend into a bifid spinous process. The lower cervical spine is composed of the third to the seventh vertebrae which are all very similar. Each vertebral body is quite small (Fig. 4). Its height is greater posteriorly than anteriorly and it is concave on its upper aspect and convex on its lower. On its upper margin it is lipped by a raised edge of bone. The anteroinferior border of the vertebral body projects over the anterosuperior border of the lower vertebra. There are six cervical discs, because there is no disc between the upper two joints. The first disc is between the axis (C2) and C3. From this level downwards to the C7–T1 joint they link together and separate the vertebral bodies. Each is named after the vertebra that lies above: e.g. the C4 disc is the disc between the C4 and C5 vertebrae (Fig. 5). The disc, comprised of an annulus fibrosus, a nucleus pulposus and two cartilaginous endplates, has the same functions as the lumbar disc, and so will not be discussed in detail (see Ch. 31, Applied Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine). There are, however, some differences (Table 1). At the cervical spine the discs are more effectively within the spine than they are at the thoracic or lumbar levels because of the superior concavity and inferior convexity of each vertebral body. They are also about one-third thicker anteriorly than posteriorly, which gives the cervical spine a lordotic curve that is not related to the shape of the vertebral bodies. The annulus fibrosus is also thicker in its posterior part than it is in the lumbar spine. The further down the spine, the more the nucleus pulposus lies anteriorly in the disc, and it disappears earlier in life than it does in the lumbar spine. For both these reasons, nuclear disc prolapses are uncommon after the age of 30. Table 1 Differences between the cervical and lumbar discs The occipital condyles are arcuate in the sagittal plane and fit into the cup-shaped superior articular surfaces of the atlas (Fig. 6). These joints only allow moderate flexion–extension (13–15°) and lateral flexion (3–8°) movements (Fig. 7). Axial rotation is not possible at these joints.

Applied anatomy of the cervical spine

Bones

Upper cervical spine

The atlas

The axis

Lower cervical spine

Intervertebral discs

Cervical

Lumbar

Contained by vertebral bodies

Not contained by vertebral bodies

Thicker anteriorly than posteriorly

Equal height

Annulus thicker posteriorly

Annulus weaker posteriorly

Nucleus in anterior part of disc

Nucleus in posterior part of disc

Joints

Occipitoatlantoaxial joints

anatomy of the cervical spine