CHAPTER 33 Amputations and Prosthetic Replacement

Amputations about the shoulder joint are infrequent. Although exact figures are not available, it is estimated that less than 5% of all major amputations occur at this level. The cross-sectional anatomy at the shoulder is complex. The standard techniques presented in this chapter are generally accepted as being based on well-established anatomic, surgical, and prosthetic considerations. Because many of these amputations are performed for complicated neoplasms and severe trauma, considerable surgical ingenuity is often required. The nature of the pathologic process requiring the amputation will direct the surgeon to emphasize plastic and reconstructive surgical principles to best use the available tissues and permit uncomplicated healing.

TYPES OF AMPUTATIONS

Amputations that preserve the distal end of the extremity are rarely performed, except in certain cases of tumor, but they may occasionally be indicated for the residual effects of chronic infection or radiation damage and, in particular, for a patient who refuses ablation of the limb. Preservation of the neurovascular supply to the distal part of the extremity is, of course, a necessity. The patient will have a degree of hand and elbow function, depending on the nature of the partial shoulder resection, but will be severely limited in overall function of the limb because of an inability to appropriately position the arm and the hand. The hand can function only at the side as the extremity dangles without stability. An orthotic support can assist in hand placement. The intercalary shoulder resection was suggested by Tikhoff, a Russian surgeon; however, the procedure was first performed by Linberg. This unusual block resection of the shoulder area was developed for patients who refused a more radical procedure for certain tumors or for instances in which the tumor did not involve the neurovascular bundle and the distal end of the extremity could be preserved. It involves resection of the scapula; most of the clavicle; and the head, neck, and a portion of the proximal shaft of the humerus, as well as involved soft tissues. The distal portion of the limb, the vascular supply, and the brachial plexus are preserved.

A scapulectomy alone may be performed for primary bone tumors. Syme first described the technique in 1864.1 Its indications are rare because the malignancy is not usually confined to the scapula itself. Adequate function without prosthetic assistance is expected, although the limb will be left weakened.

SPECIFIC PROCEDURES

Amputation Through the Surgical Neck and Shaft of the Humerus

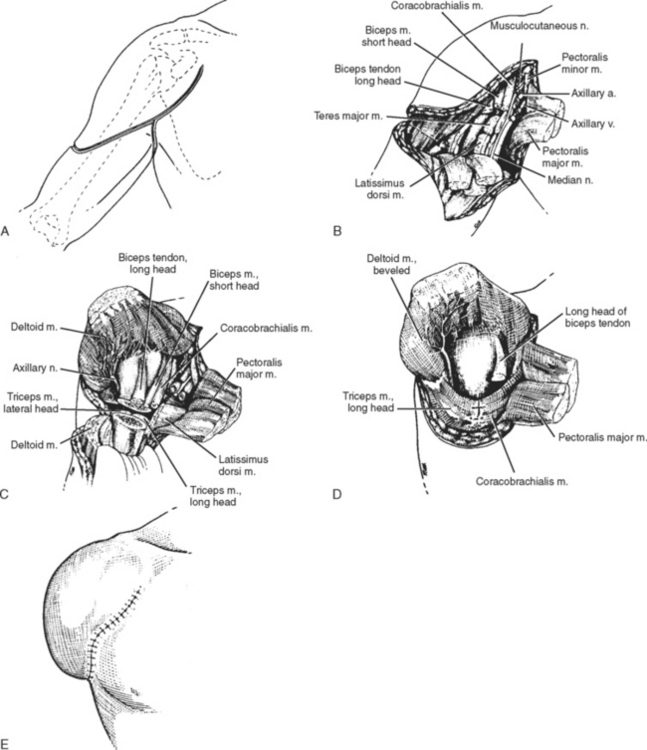

Exposure is obtained through the lateral aspect of the shoulder area. The patient is placed supine on the operating table, with support beneath the shoulder to allow access to the entire shoulder area. The arm is draped free. The incision begins anteriorly at the level of the coracoid process. It is carried distally, follows the anterior border of the deltoid muscle, and crosses the lateral aspect of the proximal end of the humerus just below the level of the deltoid insertion. It continues along the posterior border of the deltoid muscle to the level of the axillary fold, then transversely across the axilla to connect with the anterior of the arm (Fig. 33-1). Care should be taken to leave an adequate amount of skin, particularly in the axilla. Skin closure can be compromised when the flap is short and tight medially.

The median, ulnar, radial, and musculocutaneous nerves are then isolated individually, drawn down into the wound gently, ligated circumferentially, and sectioned with a knife distal to the ligatures. They then retract comfortably under the pectoralis minor muscle.

With the proximal end of the humerus thus isolated, it is divided at the desired level with a small-toothed reciprocating power saw. Sharp bone margins are rounded smooth, and the wound is thoroughly irrigated. In very short transhumeral amputations, the resulting muscle imbalance can pull the residual arm into 90 degrees of abduction. Baumgartner has recommended that surgeons consider arthrodesis in a functional position to prevent this complication in very short amputations.2

Disarticulation of the Shoulder

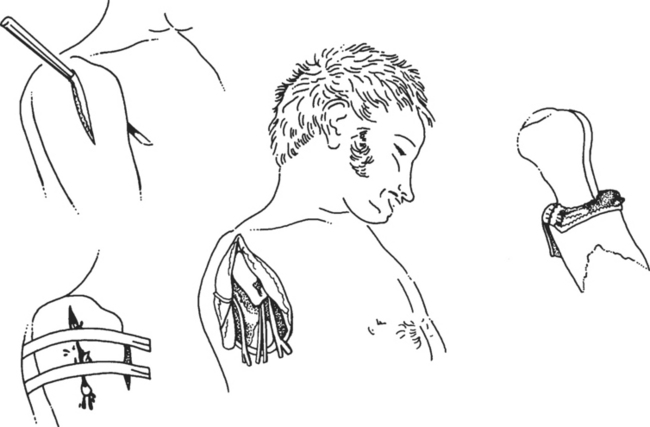

Shoulder disarticulation has been referred to in many military medical writings over the centuries. Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, military surgeon to Napoleon for 16 years, described and illustrated his technique, which established the standard of the day.3 Baron Larrey was a skilled anatomist and an expert surgical technician; it has been said that he amputated more limbs than any surgeon before or since. He described performing 200 thigh amputations in one 24-hour period while accompanying Napoleon during the battle of Borodino. (A modified illustration of his shoulder disarticulation technique is shown in Fig. 33-2.)

FIGURE 33-2 Modified illustration of shoulder disarticulation performed by Baron Larrey and described in 1797.

(Redrawn from Larrey DJ: Memoire sur les Amputations des Membres à La Suite des Coups de Feu Etaye de Plusieurs Observations. Paris: Du Pont, 1797.)

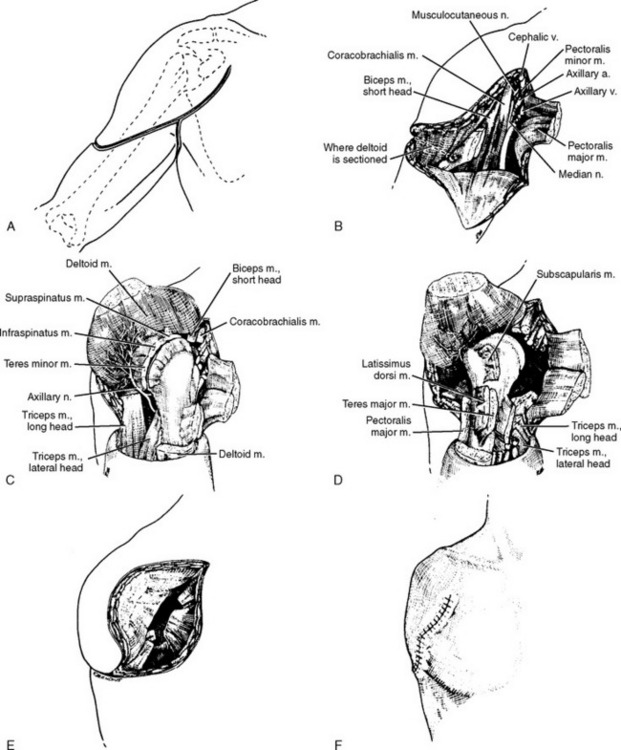

The patient is positioned supine with support under the affected shoulder to allow complete access to the shoulder and shoulder girdle area. The incision begins anteriorly at the coracoid process, continues along the anterior border of the deltoid muscle, and is carried transversely across the lateral aspect of the proximal end of the humerus at the level of the deltoid muscle insertion (Fig. 33-3A). The incision is continued superiorly along the posterior border of the muscle to end at the posterior axillary fold, where the two ends of the incision are joined with a second incision passing across the axilla. The cephalic vein is identified in the deltopectoral groove and ligated. The deltoid and pectoralis major muscles are separated anteriorly. The deltoid is then retracted laterally. The pectoralis major is divided at its humeral insertion and reflected medially.

The interval between the coracobrachialis and the short head of the biceps is opened to expose the neurovascular bundle (see Fig. 33-3B). The axillary artery and vein are doubly ligated independently of each other and then sectioned. The thoracoacromial artery, just proximal to the pectoralis minor muscle, is identified, ligated, and divided. The vessels then retract superiorly under the pectoralis minor muscle. The median, ulnar, musculocutaneous, and radial nerves can then be identified, drawn distally into the wound gently, ligated with a circumferential suture, and sectioned under mild tension. They then retract beneath the pectoralis minor muscle.

The coracobrachialis and short head of the biceps are next sectioned near their insertions on the coracoid process (see Fig. 33-3C). The deltoid muscle is freed from its insertion on the humerus and reflected superiorly to expose the capsule of the shoulder joint. The teres major and latissimus dorsi muscles are divided at their insertions, and the arm is placed in internal rotation to expose the short external rotator muscles, the posterior aspect of the shoulder joint, and the adjacent fascia. All these structures are divided.

The arm is rotated into full external rotation, and the anterior aspect of the joint capsule, the remaining shoulder capsule, and the subscapularis muscle are sectioned (see Fig. 33-3D). The triceps muscle is divided near its insertion, and the limb is severed from the trunk by dividing the inferior capsule of the shoulder joint. The cut ends of all muscles are reflected into the glenoid cavity and sutured there to help fill the hollow left by removal of the humeral head (see Fig. 33-3E).

The deltoid muscle flap is brought down inferiorly to permit suturing just below the glenoid (see Fig. 33-3F). Closure is accomplished without tension by using optimal wound closure technique. Drains, either suction or through-and-through, or both, are inserted and closure is carried out in layers. Compression dressings are applied to assist in eliminating any residual dead space. Scar adhesions about the site of surgery can be painful and can complicate both cosmesis and functional prosthetic fit. Drains are usually removed in 48 hours, and effective compression dressings are reapplied.

Scapulothoracic Amputation (Forequarter Amputation)

Anterior Approach

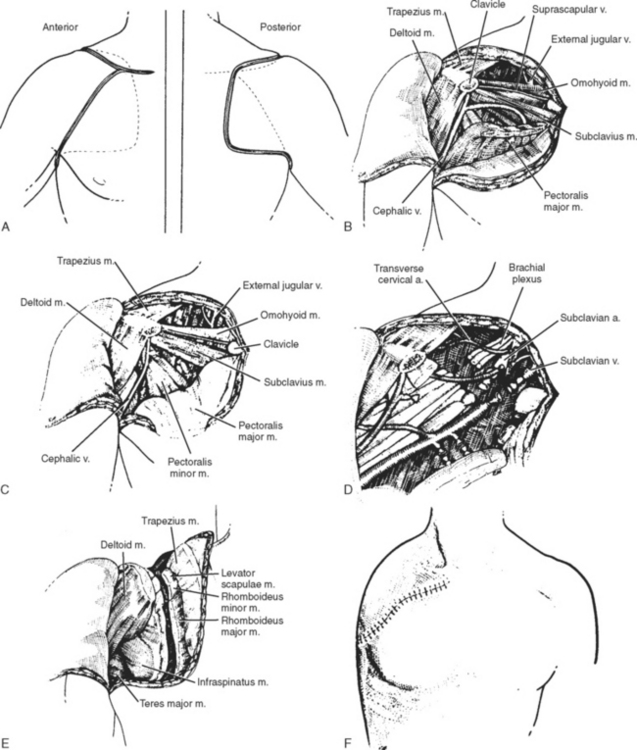

The incision begins 4 cm lateral to the sternoclavicular articulation at a point corresponding to the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle insertion (Fig. 33-4A). It follows the entire anterior aspect of the clavicle and passes over the top of the shoulder to the spine of the scapula. At this point, the arm is flexed over the chest to rotate the scapula forward and outward so that its bony contour is outlined in greater relief. The posterior aspect of the upper incision then proceeds down over the spine to its vertical border, which it follows distally to the angle of the scapula. The lower portion of the ellipse starts in the middle third of the clavicle and passes downward in the groove between the deltoid and the pectoral muscles to the anterior axillary fold. The arm is abducted, and the incision is continued across the axilla at the level of the junction of the skin of the arm and the axillary skin. As the incision passes the posterior axillary fold, it continues medially across the back to join the upper incision at the angle of the scapula.

Section of the Anterior Muscles

The head is bent toward the normal side so that the sternocleidomastoid muscle may be better outlined, and the pectoralis major muscle is severed from its clavicular insertion. The dissection starts at the lateral border of the insertion and proceeds close to bone to the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The pectoralis major muscle is then reflected downward and medially. If further exposure is needed, the humeral insertion of the pectoralis major may be divided. The upper border of the clavicle is exposed by sectioning the superficial layer of the deep fascia along the upper border of the clavicle as far medially as the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Further dissection beneath the clavicle is carried out with a finger or a blunt curved dissector. The external jugular vein, which emerges just above the clavicle at the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid, may be sectioned and ligated if it is in the way.

The clavicle is now divided with a Gigli or reciprocating power saw at the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It is not desirable to section the clavicle more medially because of the danger of injuring the veins that hug its medial inch. The clavicle is sectioned at or near the acromioclavicular joint, and the freed portion is removed (see Fig. 33-4B). If the humeral insertion of the pectoralis major muscle has not already been sectioned, this is done. This whole muscle may then be reflected downward, and the entire shoulder girdle may be retracted outward and downward so that the axillary and subclavian region is in full view. The axillary fascia is sectioned, the pectoralis minor is severed from its coracoid insertion, and the costocoracoid membrane that lies between the pectoralis minor and the subclavius is divided (see Fig. 33-4D). The second layer of deep fascia up to the level of the omohyoid muscle, the periosteum at the back of the clavicle, and the subclavius are divided to complete exposure of the neurovascular bundle.

Section of the Posterior Muscles

The arm is placed across the chest and held with gentle downward traction. The posterior incision is deepened through the fascia, and the skin is retracted medially. The remaining muscles fixing the shoulder girdle to the scapula are divided as they are encountered from above downward. The muscles holding the scapula to the thorax are divided (see Fig. 33-4E). The incision starts at the insertion of the trapezius to the clavicle and acromion and is carried downward along the upper border of the spine of the scapula. After sectioning, each muscle is retracted medially. The muscles along the superior angle of the vertebral border of the scapula—the omohyoid, levator scapulae, rhomboideus major and minor, and serratus anterior—are sectioned by placing double clamps near their insertions and cutting between the clamps from above downward. The extremity is removed, and hemostasis is achieved with meticulous care.

Closure

Careful inspection is made to ensure that all malignant tissue has been removed. If the pectoralis major has not, of necessity, been removed, it should be sutured to the trapezius muscle. Closure is accomplished in layers, with all remaining muscular structures grouped over the lateral chest wall to provide as much padding as possible. The skin flaps are brought together and tailored to form an accurate approximation. The wound is closed with interrupted sutures (see Fig. 33-4F), and adequate drainage is established. Dry dressings are applied, and a snug pressure dressing is placed over the lateral chest wall. The drains are removed in 48 to 72 hours, and the sutures are removed between the 10th and 14th days.

Posterior Approach

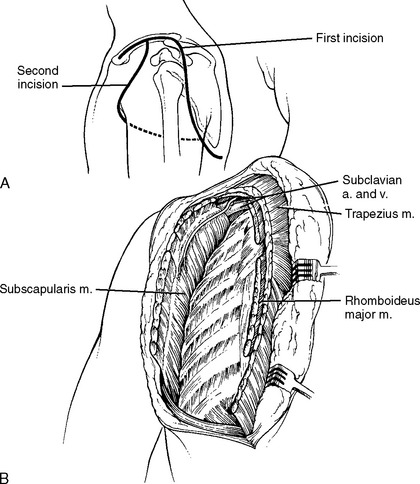

Littlewood, in 1922, described a technique of scapulothoracic amputation that requires two incisions and approaches the shoulder area from the posterior aspect (Fig. 33-5).4 This posterior approach is considered technically easier. We have used the conventional (Berger) anterior approach for patients under our care over the years but recognize the advantages of the two-incision technique, especially in atypical cases.

The patient is positioned on the uninvolved side near the edge of the operating table. Two incisions are required (see Fig. 33-5): one posterior (cervicoscapular) and one anterior (pectoroaxillary). The posterior incision is made first. Beginning at the medial end of the clavicle, the incision extends laterally for the entire length of the bone, carries over the acromion process to the posterior axillary fold, continues along the axillary border of the scapula to a point inferior to the scapular angle, and finally curves medially to end 5 cm (2 in) from the midline of the back. From the scapular muscles, an entire full-thickness flap of skin and subcutaneous tissue is elevated medially to a point just medial to the vertebral border of the scapula.

The anterior incision is then begun at the middle of the clavicle. It curves inferiorly just lateral to but parallel with the deltopectoral groove, extends across the anterior axillary fold, and finally continues inferiorly and posteriorly to join the posterior axillary incision at the lower third of the axillary border of the scapula. As the final step in the operation, the pectoralis major and minor muscles are divided and the limb is removed. The skin flaps are trimmed to allow a snug closure, and their edges are sutured with interrupted sutures of nonabsorbable material. Effective through-and-through and suction drains are inserted to eliminate any accumulation of fluid. Firm chest wall pressure dressings are required. Drains may be removed after 48 hours.

Depending on the nature and extent of the pathologic process, surgical variations might be indicated, such as the need for regional lymph node resection and soft tissue removal at the chest wall when the tumor has extended into these structures. Skin grafts, including composite tissues, may be necessary to obtain primary or secondary closure. Several recent articles highlight the use of free tissue transfer, occasionally from the distal aspect of the amputated limb, as means to obtain closure after radical tumor resection.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree