Chapter 142 Affective Disorders

Diagnostic Summary

Diagnostic Summary

Depression

• Poor appetite with weight loss or increased appetite with weight gain

• Physical hyperactivity or inactivity

• Loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities or decrease in sexual drive

• Loss of energy and feelings of fatigue

• Feelings of worthlessness, self-reproach, or inappropriate guilt

• Diminished ability to think or concentrate

Dysthymia

Manic Phase

• Mood is typically elation, but irritability and frank hostility are not uncommon.

• Signs and symptoms include inflated self-esteem, grandiose delusions, boasting, racing thoughts, decreased need for sleep, psychomotor acceleration, weight loss due to increased activity, and lack of attention to dietary habits.

Introduction

Introduction

• The individual’s genetic makeup

• The particular age of neuronal development, which results in age-specific variability

• The functional plasticity of the brain during development, which contributes to the functional and structural shaping of the system

• The motivational state, affected by various biological drives, which channels behavior toward specific goals by setting priorities or prejudicing the context of particular types of incoming information

• The availability of memory-stored information and related processing strategies

• The environment, which can adjust the incoming information, depending on its momentary significance

• Disease or lesion of the brain, which can cause aberrant functional states

• Conditions of the metabolic/hormonal system or the internal biochemical environment of the central nervous system (CNS)

Depression

Depression

Approximately 20 million Americans suffer true clinical depression each year, and more than 30 million Americans take antidepressant drugs or anxiolytics. The World Health Organization predicts that depression will become the second most burdensome disease in the world in the coming decade, with the greatest burden of disease in North America and the United Kingdom.1 The obvious question is: Why are so many people depressed? From a nonphysiologic standpoint, several basic theoretic models of depression attempt to answer this question.

• The “aggression-turned-inward” construct, which, although apparent in many clinical cases, has no substantial proof.

• The “loss model,” which postulates that depression is a reaction to the loss of a person, thing, status, self-esteem, or even a habit pattern.

• The “interpersonal relationship” approach, which uses behavioral concepts (e.g., the person who is depressed uses depression as a way of controlling other people, including doctors). This can be an extension and outgrowth of such simple behaviors as pouting, silence, or ignoring something or someone. It fails to serve the need, and the problem worsens.

• The “learned helplessness” model, which theorizes that depression is the result of habitual feelings of pessimism and hopelessness.

• The “biogenic amine” hypothesis, which stresses biochemical derangement characterized by imbalances of biogenic amines.

• The analytical (or adaptive) rumination hypothesis, whereby the ruminative cognitive processes of a person with depression facilitate the solution of complex social problems.

Although the more physiologic biogenic amine model of depression is now the dominant medical model of depression, there is much value to counseling, especially in clear cases of psychological etiology. Of the various psychological theories of depression, the one that may have the most merit is the learned helplessness model developed by Martin Seligman. During the 1960s, Seligman discovered that animals could be trained to be helpless. His animal model provided a valuable clue to human depression as well as serving as the research model to test antidepressant drugs.2

The Learned Helplessness Model

As predicted, the first and third groups of dogs learned within seconds that they could avoid the shock by jumping over the barrier, whereas the dogs in the second group would simply lie down and not even make an effort to jump over the barrier, although they could see the shockless side of the shuttle box. Seligman and his colleagues went on to show that many humans react in an identical fashion to the animals in these experiments.

Outside the laboratory setting, Seligman discovered that the determining factor on how a person would react to uncontrollable events, either “bad” or “good,” was their explanatory style—the way in which they explained events. Optimistic people were immune to becoming helpless and depressed. However, individuals who were pessimistic were extremely likely to become depressed when something went wrong in their lives. Seligman and other researchers also found a direct correlation between an individual’s level of optimism and the likelihood of developing not only clinical depression but other illnesses as well.2 In one of the longer studies, patients were followed for a total of 35 years. Optimists rarely got depressed, but pessimists were extremely likely to battle depression and other psychological disturbances.

Therapeutic Considerations

Therapeutic Considerations

Modern psychiatry focuses on manipulating neurotransmitter levels in the brain rather than identifying and eliminating the psychological factors responsible for producing the imbalances in serotonin, dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and other neurotransmitters. Although the use of antidepressants may be important in treating severe depressive illness and threatened suicide, antidepressants have not been shown to work any better than placebo in cases of mild to moderate depression, the most common reason for prescription medication.4 In fact, 25% of patients taking antidepressants do not even have a diagnosable psychiatric problem.5 So, the bottom line is that millions of people are using antidepressants for a problem they do not have, and for the people who do have a diagnosable condition, these medications generally do not work. This is a clear mandate to consider natural medicine therapeutics for these mood disorders.

Depression can often be due to an underlying organic or physiologic cause (Box 142-1). Identification and elimination of such an underlying cause should be the primary therapy. In this spirit, the depressed individual needs a comprehensive clinical evaluation.

BOX 142-1 Organic and Physiologic Factors That May Underlie Depression

• Nutrient deficiency or excess

• Drugs (e.g., prescription, illicit, alcohol, caffeine, nicotine)

• Stress and feelings of being overwhelmed

Counseling

Although many counseling techniques are useful, the one with the most merit and support in the medical literature is cognitive behavorial therapy (CBT). In fact, CBT has been shown to be as effective as antidepressant drugs in treating moderate depression.5,6 Although there is a high rate of relapse of depression when drugs are used, the relapse rate for cognitive therapy is much lower. People taking drugs for depression tend to stay on them for the rest of their lives. That is not the case with CBT, because the patient is taught new skills with which to deal with depression.7

A second useful technique is interpersonal therapy (IPT), which generally focuses on improving communication skills and increasing self-confidence and self-esteem. Interpersonal therapy is often used with depression due to loss of a loved one, during life transitions (such as becoming a parent or changing careers), feelings of isolation, and relationship conflicts. A study of 233 women with a history of recurrent depression were given acute IPT once a week, twice a month, or once a month. Of these subjects, 112 achieved remission (as defined as a rating of less than 7 for 3 consecutive weeks on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDS]) with IPT alone. It was concluded that dosage was not a factor. Interestingly, the once-monthly frequency appeared to be as effective as the once weekly in preventing the recurrence of depressive symptoms. However, it was noted that the attrition rate for twice-monthly therapy was the lowest, raising the idea that patient preferences for treatment frequency may be a factor in determining effectiveness of treatment.8

Hormonal Factors

Thyroid Function

Depressive illness is often a first or early manifestation of thyroid disease, as even subtle decreases in available thyroid hormone are suspected of producing symptoms.9,10 The link between hypothyroidism and depression is well known, but whether the thyroid hypofunction is a result of depression-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid dysfunction or of thyroid hypofunction, remains to be definitively determined. It is probably a combination. According to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, one in ten Americans suffers from thyroid disease, and almost one half of these remain undiagnosed as hypothyroid. Many of these individuals may be susceptible to depression. Depressed patients should be screened for hypothyroidism, particularly if they complain of fatigue or have other symptoms suggestive of hypothyroidism.

Stress and Adrenal Function

That elevations in cortisol reflect a disturbance in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the basis of the dexamethasone suppression test (discussed later). Defects in HPA regulation seen in affective disorders include excessive cortisol secretion independent of stress responses, abnormal nocturnal release of cortisol, and inadequate suppression by dexamethasone.11

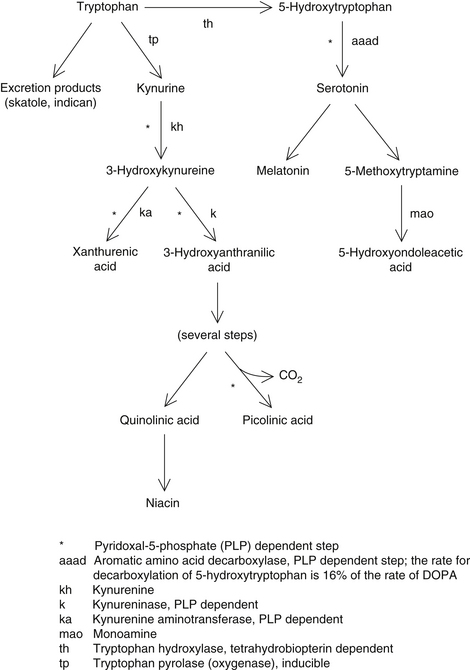

The CNS effects of increased endogenous release of cortisol mirror the effects of exogenous cortisol: depression, mania, nervousness, insomnia, and, at high levels, schizophrenia. The effects of glucocorticoids on mood are related to their induction of tryptophan oxygenase (Figure 142-1). This results in the shunting of tryptophan to the kynurenine pathway at the expense of serotonin and melatonin synthesis.12

Tests of Hypothalamic-Pituitary Function

The two tests widely used as aids in classifying psychiatric conditions are the dexamethasone suppression test (DST) and the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) test.13,14 The basic function of these tests is to determine if the condition is a result of hypothalamic dysfunction and to categorize the psychiatric illness (e.g., severe major affective disorders versus severe psychotic disorders).

Because thyroid hormone assays cannot detect all cases of thyroid hypofunction, they are not an effective screening procedure. The TRH test is significantly more sensitive in diagnosing “subclinical hypothyroidism.”15 A grading system for hypothyroidism as determined by the TRH test has been proposed as follows:

• Grade 3 (subclinical hypothyroidism—4%). Patients are usually without classic signs of thyroid failure and have normal T3RU, T4, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels but definitely abnormal TSH response to the TRH test.

• Grade 2 (mild hypothyroidism—3.6%). Patients may have mild isolated clinical signs or symptoms of hypothyroidism but demonstrate normal T3RU and T4 levels. Baseline

TSH levels are elevated, and there is an abnormal TRH test.

• Grade 1 (overt hypothyroidism—1%). Patients demonstrate signs and symptoms of classic hypothyroidism along with abnormal laboratory values (i.e., reduced T3RU and T4 levels, increased TSH levels, and abnormal TRH response).

Environmental Toxins

Heavy metals (lead, mercury, cadmium, arsenic, nickel, and aluminum), as well as solvents (e.g., cleaning materials, formaldehyde, toluene, benzene), pesticides, and herbicides have an affinity to nervous tissue. As a result, various psychological and neurologic symptoms can occur, including the following16–18:

A detailed medical history and hair mineral analysis are possible screening mechanisms for environmental toxicity. Refer to Chapter 23 (Metal Toxicity: Assessment of Exposure and Retention) for further discussion.

Lifestyle Factors

Smoking

Cigarette smoking is one of the major factors contributing to premature death. Cigarette smoking is also a significant factor in depression. Central to the effect of nicotine is the stimulation of adrenal hormones, including the secretion of cortisol. Elevated cortisol levels are a well-recognized feature of depression.3 One of the key effects of cortisol (and stress) on mood is the activation of tryptophan oxygenase, resulting in the delivery of less tryptophan to the brain. Because the level of serotonin in the brain depends on the level of tryptophan, cortisol dramatically reduces the level of serotonin and melatonin. In addition, cortisol also down regulates serotonin receptors in the brain, making them less sensitive to the serotonin that is available.

Cigarette smoking also leads to a relative vitamin C deficiency, as the vitamin C is used to detoxify the cigarette smoke. Low levels of vitamin C in the brain can result in depression and hysteria.19

Alcohol

Alcohol, a brain depressant, increases adrenal hormone output, interferes with many brain cell processes, and disrupts normal sleep cycles. Chronic alcohol ingestion will also deplete a number of nutrients and mood-enhancing prostaglandin E1, all which will disrupt mood. Alcohol ingestion also leads to hypoglycemia. The resultant drop in blood sugar produces a craving for sugar because it can quickly elevate blood sugar. Unfortunately, increased sugar consumption ultimately aggravates the hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia aggravates the mental and emotional problems of the alcoholic. Treatment options that can address both the depression and addiction of the individual simultaneously are best.20 Supplementation with selenium can improve mood stability and help change drinking habits as well (see the section on selenium later).

Caffeine

Although caffeine is a well-known stimulant, the intensity of response to caffeine varies greatly, with people prone to feeling depressed or anxious tending to be especially sensitive to caffeine. The term caffeinism is used to describe a clinical syndrome similar to generalized anxiety and panic disorders; its symptoms include depression, nervousness, palpitations, irritability, and recurrent headache.21

Several studies have looked at caffeine intake and depression. For example, one study found that among healthy college students, those who drank moderate to large amounts of coffee scored higher on a depression scale than those who drank less. Interestingly, the heavier coffee drinkers also tended to perform significantly less well academically.22 Several other studies have shown that depressed patients tend to consume fairly large amounts of caffeine (e.g., more than 700 mg/day).23,24 In addition, caffeine intake has been positively correlated with the degree of mental illness in psychiatric patients.25,26

The combination of caffeine and refined sugar seems to be even worse than either substance consumed alone. Several studies have found an association between this combination and depression. In one of the most interesting studies, 21 women and 2 men responded to an advertisement requesting volunteers “who feel depressed and don’t know why, often feel tired even though they sleep a lot, are very moody, and generally seem to feel bad most of the time.”27 After baseline psychological testing, the subjects were placed on a caffeine- and sucrose-free diet for 1 week. Those subjects who reported substantial improvement were then challenged in a double-blind fashion. They took either a capsule containing caffeine and a Kool-Aid drink sweetened with sugar or a capsule containing cellulose and a Kool-Aid drink sweetened with NutraSweet. Each challenge lasted up to 6 days. About 50% of test subjects receiving the caffeine and sucrose became depressed during the test period.

Another study using a similar format found that 7 of 16 depressed patients were depressed with the caffeine and sucrose challenge but symptom-free during the caffeine- and sucrose-free diet and test period with cellulose and NutraSweet.28

Exercise

Regular exercise may be the most powerful natural antidepressant available. In fact, many of the beneficial effects of exercise noted in the prevention of heart disease may be related just as much to its ability to improve mood as to its improvement of cardiovascular function.29 Furthermore, obesity is associated with depression.30 Various community and clinical studies have clearly indicated that exercise has profound antidepressant effects.31 These studies have shown that increased participation in exercise, sports, and physical activities is strongly associated with decreased symptoms of anxiety, depression, and malaise. Furthermore, people who participate in regular exercise have higher self-esteem, feel better, and are much happier than people who do not exercise.

Much of the mood-elevating effect of exercise may be attributed to the fact that regular exercise has been shown to increase the level of endorphins, which are directly correlated with mood.32 One of the most interesting studies that examined the role of exercise and endorphins in depression compared the beta-endorphin levels and depression profiles of 10 joggers with those of 10 sedentary men of the same age. The 10 sedentary men tested were more depressed, perceived greater stress in their lives, and had higher levels of cortisol and lower levels of beta-endorphins. As the researchers stated, this “reaffirms that depression is very sensitive to exercise and helps firm up a biochemical link between physical activity and depression.”33

At least 100 clinical studies have now evaluated the efficacy of an exercise program in the treatment of depression. In an analysis of the 64 studies before 1980, physical fitness training was shown to relieve depression and improve self-esteem and work behavior.34

Unfortunately, the quality of many of the studies was less than ideal. However, because of the good results noted in the analysis of these studies, a flurry of well-designed studies were conducted in the 1980s to better determine how effective exercise could be as a therapy. These studies used stricter scientific criteria than the earlier ones, yet they produced similar results. It was concluded that exercise can be as effective as other treatments, including drugs and psychotherapy.35 More recently, even stricter studies have further demonstrated that regular exercise is a powerful antidepressant.31,36,37

Nutrition

A deficiency of any single nutrient can alter brain function and lead to depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders (Table 142-1). However, the role of nutrient deficiency is just the tip of the iceberg with regard to the role of effects on the brain and mood. Melvin Werbach, MD, has stated the following38:

TABLE 142-1 Behavioral Effects of Some Vitamin Deficiencies

| DEFICIENT VITAMINS | BEHAVIORAL EFFECTS |

|---|---|

| Thiamine | Korsakoff’s psychosis, mental depression, apathy, anxiety, irritability |

| Riboflavin | Depression, irritability |

| Niacin | Apathy, anxiety, depression, hyperirritability, mania, memory deficits, delirium, organic dementia, emotional lability |

| Biotin | Depression, extreme lassitude, somnolence |

| Pantothenic acid | Restlessness, irritability, depression, fatigue |

| Vitamin B6 | Depression, irritability, sensitivity to sound |

| Folic acid | Forgetfulness, insomnia, apathy, irritability, depression, psychosis, delirium, dementia |

| Vitamin B12 | Psychotic states, depression, irritability, confusion, memory loss, hallucinations, delusions, paranoia |

| Vitamin C | Lassitude, hypochondriasis, depression, hysteria |

Dietary Guidelines

Several studies have shown hypoglycemia to be common in depressed individuals.39–42 A study of six countries showed a highly significant correlation between sugar consumption and the annual rate of depression.43 Simply eliminating refined carbohydrate from the diet is occasionally all that is necessary for effective therapy in patients who have depression due to reactive hypoglycemia.

The dietary guidelines for depression are identical to those for optimal health. It is now well established that certain dietary practices cause and others prevent a wide range of diseases. Quite simply, a health-promoting diet provides optimal levels of all known nutrients and low levels of food components that are detrimental to health, such as sugar, saturated fats, cholesterol, salt, and food additives. A health-promoting diet is rich in whole “natural” and unprocessed foods. It is especially high in plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, grains, beans, seeds, and nuts, because these foods contain not only valuable nutrients but also additional compounds that have remarkable health-promoting properties. Although no one diet is a fit for everyone, a 4½ year study of over 10,000 people reported that those who ate a healthy Mediterranean diet, as detailed in Chapter 44, were about one half as likely to develop depression than those who said they did not stick to the diet.44

Folic Acid and Vitamin B12

Folic acid and vitamin B12 function together in many biochemical processes. Folic acid deficiency is the most common nutrient deficiency in the world. In studies of depressed patients, 31% to 35% have been shown to be deficient in folic acid.45–48 In elderly patients this percentage may be even higher. Studies have found that among elderly patients admitted to a psychiatric ward, the number with folic acid deficiency ranged from 35% to 92.6%.49,50 Depression is the most common symptom of a folic acid deficiency. Vitamin B12 deficiency is less common than that of folic acid but it can also cause depression, especially in the elderly.51,52 Correcting folic acid and vitamin B12 deficiencies results in a dramatic improvement in mood.

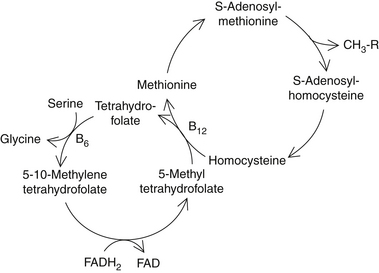

Folic acid, vitamin B12, and S-adenosylmethionine, a form of the amino acid methionine known as SAMe, function as “methyl donors” (Figure 142-2). They carry and donate methyl molecules to important brain compounds including neurotransmitters. SAMe is the major methyl donor in the body. The antidepressant effects of folic acid appear to be a result of raising brain SAMe content.

One of the key brain compounds dependent on methylation is tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). This compound functions as an essential coenzyme in the activation of enzymes that manufacture monoamine neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine from their corresponding amino acids. Patients with recurrent depression have been shown to have reduced BH4 synthesis, probably as a result of low SAMe levels. BH4 supplementation has been shown to produce dramatic results in these patients.53,54 Unfortunately BH4 is not currently available commercially. However, because BH4 synthesis is stimulated by folic acid, vitamin B12, and vitamin C, it is possible that increasing these vitamin levels in the brain may stimulate BH4 formation and the synthesis of monoamines like serotonin.55

Some evidence supports the contention that supplementing the diet with folic acid, vitamin C, and vitamin B12 can increase BH4 levels. In addition, the folic acid supplementation and promotion of methylation reactions have been shown to increase the serotonin content.51–53 The serotonin-elevating effects are undoubtedly responsible for much of the antidepressant effects of folic acid and vitamin B12.

One review of three folate trials involving 247 depressed patients has been published.59 Two of the studies involving 151 people assessed the use of folate in addition to other treatments and found that adding folate reduced HDS scores on average by a further 2.65. One of the studies, involving 96 people, assessed the use of folate instead of the antidepressant trazodone. This study did not find a significant benefit from the use of folate. Although the authors of this analysis considered these data “limited,” they acknowledged the potential role of folate as a supplement to treat depression. No side effects or toxicities were noted in any of the studies reviewed.

Typically, the dosages of folic acid in the antidepressant clinical studies have been high: 15 to 50 mg. High-dose folic acid therapy is safe except in patients with epilepsy and has been shown to be as effective.60

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree