Adaptive Seating in the Management of Neuromuscular and Musculoskeletal Impairment

Barbara Crane

Learning Objectives

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Describe the population of individuals who use wheelchairs and adaptive seating.

2. Identify the elements of a basic wheelchair and seating evaluation.

3. List potential outcomes for adaptive seating and mobility intervention.

4. Summarize biomechanical principles related to adaptive seating and wheeled mobility.

Neuromuscular and musculoskeletal impairments often limit a person’s functional gait potential. When this occurs, adaptive seating support and wheeled mobility interventions are essential in returning a person to a maximal level of independent function. Individuals use their wheeled mobility device for many hours each day. People who use wheeled mobility devices (wheelchairs or scooters) for some or all of their mobility often require adaptive seating support. Additionally, individuals who use wheeled mobility devices often require assistance for other activities of daily living and may require postural support and balance in a seated position. Individuals with neuromuscular impairments typically require specialized seating support to attain a maximal level of independent function, comfort, safety, and quality of life. Individuals with musculoskeletal impairment in the absence of neurological deficits may also require postural support because of the amount of time they spend in a seated posture or, in some cases, because of the inability to either stand or walk.

Individuals who use wheelchairs and adaptive seating systems are of all age groups and races. They use their wheelchairs in many different environments and for many different reasons. Some are full-time wheelchair users because they cannot stand or walk. Others spend part of their day in the wheelchair to augment their mobility over long distances or on uneven surfaces. Some use wheelchairs for short-term conditions that resolve within weeks or months, such as lower extremity fractures or joint replacement surgeries. Others use wheelchairs long-term because of permanent disabling conditions.

There are approximately 1.7 million community-dwelling people in the United States who use wheelchairs or powered scooters to assist them with mobility.1 Of these, approximately 1.5 million use manual wheelchairs, 155,000 use electric- powered wheelchairs, and 142,000 use electric-powered scooters.2 In addition to these permanent users, there are likely to be several million part-time or temporary wheeled mobility device users at any given time in the United States, not including individuals residing in institutional settings. The National Medical Expenditure Survey conducted in 1987 indicated there were 2.5 million individuals residing in long-term care facilities, and of these, more than 50% use wheelchairs for mobility.3,4 Individuals who use wheelchairs range from very young children who never attain the ability to walk to very old adults who have lost this ability because of various disabling conditions and processes.

Among all age groups, the leading condition associated with wheelchair use is cerebrovascular disease. Among individuals ages 18 to 64 years, the leading condition associated with wheelchair use is multiple sclerosis.1 Other conditions commonly associated with wheelchair use include osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, congenital absence or amputation of lower extremities, tetraplegia and paraplegia, cardiopulmonary diseases and disorders (e.g., emphysema) that limit endurance, cerebral palsy, diabetes, and orthopedic impairment of the lower extremities.1

Individuals who use adaptive seating and wheeled mobility live in many different environments. Many live in the community independently or with assistance or support. Others live in long-term care settings or in assisted-living environments. Individuals use wheelchairs at home, school, work, and outdoors. People rely on their wheeled mobility devices to allow them to work, learn, play, care for themselves, and meet their personal goals. Therefore the assessment for and recommendation of a wheeled mobility device and seating support system is an important responsibility, which is typically undertaken by a team of trained individuals.

What is a wheelchair?

A wheelchair, or wheeled mobility device, is a complex piece of assistive technology. In addition to providing a means for mobility, this device provides the foundation for all other function, that is, activities of daily living such as bathing and dressing, work activities, and recreation. To do this, several interrelated components of the wheeled mobility device must work together to meet the needs of the individual user. The three major components of a wheelchair are the seating system (the postural support component), the wheelchair frame (the supporting structure), and the propelling structure (Figure 16-1).5 All three components provide different functions but must form an integrated unit for efficient and safe wheeled mobility. Successful integration is critical to the function of the wheelchair user.

Seating System

The seating system, or adaptive seating component, of the wheeled mobility device is primarily responsible for support and positioning of the wheelchair user or wheelchair rider. This component can be thought of as an orthotic intervention in wheeled mobility prescription.

Adaptive seating is used to promote postural support and positioning so that the user may function optimally.6 To do this, it must accomplish the following five goals:

3. Provide optimal comfort so that the seating system may be tolerated for long periods

4. Facilitate distal extremity function by providing a stable base of support for the user

Although all these goals are critical to the optimal function of any wheeled mobility device, goals must be prioritized on the basis of personal needs of each user. For example, a wheeled mobility device user with a spinal cord injury who has good overall posture but lacks sensory function requires greater emphasis on pressure management goals than on postural support.

The seating system is often divided into several components, each with responsibility for supporting different body segments. Table 16-1 summarizes the indications for each type of seating component.

Table 16-1

Postural Support Components and Indications for Use

| Postural Support Component | Indications for Use |

| Seat cushion | Wheelchair use for any amount of time (see Table 16-6 for detailed descriptions of types of seat cushions) |

| Solid seat support | Wheelchair use for any amount of time, particularly a folding wheelchair with sling seat upholstery |

| Solid back support | Wheelchair use of 4 hours or more per day Impaired sitting balance or trunk control Scoliosis or any need for lateral and posterior spinal support |

| Lateral thoracic supports | Impaired sitting balance or trunk control Flexible or fixed spinal scoliosis Need for additional lateral support for safe or efficient activities of daily living (e.g., driving) |

| Lateral pelvic supports | Impaired pelvic and lower trunk control Flexible or fixed scoliosis Medial knee supports Lower extremity adduction while sitting Hypertonicity (spasticity) of lower extremities Windswept deformities of lower extremities |

| Knee blocks | Impaired anterior stability of pelvis in wheelchair If the patient slides out of wheelchair on a regular basis Severe extensor spasticity in lower extremities |

| Head support | Impaired head control from weakness or abnormal muscle tone |

| Anterior pelvic support | Anterior/posterior instability of pelvis while sitting (e.g., falling into posterior pelvic tilt or excessive anterior tilt, sliding out of chair) |

| Anterior trunk support | Anterior trunk instability If additional support is needed for safe and efficient functional activities (e.g., wheelchair propulsion, mobility over rough terrain, driving activities, or transportation needs) |

Support Frame and Mobility Components

The support frame is integrated with the seating component and is closely linked with the propelling structure. The main purpose of the support frame is to provide a smooth integration or connection of the seating support system and the mobility component of the wheeled mobility device. Many styles of frames are available; some provide specialty purposes, such as tilt, recline, or standing frames, but the majority are configured to allow attachment of adaptive seating systems and facilitate access to the mobility structures of the device by the user.

The mobility base, or propelling structure, of the wheelchair is composed of the drive wheels, caster wheels, tires, and some type of user interface component. Goals for the mobility base focus on the facilitation of mobility within the user’s environment and can include the following:

1. Independent mobility in all environments encountered by the individual

2. Safe access to mobility and the prevention of injuries, such as overuse or secondary injuries

3. Maximum efficiency in mobility

4. Facilitation of overall function within the person’s environment

In Cook and Hussey’s Human Activity Assistive Technology model, wheeled mobility devices and seating systems are defined as “extrinsic enablers.”5 These devices facilitate or allow the user to perform many functions. A seating support system is referred to as a “general-purpose extrinsic enabler”5 because it facilitates many different functions for the user, such as self-care, recreation, or mobility. The wheeled mobility device is a “specific purpose extrinsic enabler,” meaning it specifically allows users to be mobile within their environment.

Seating and mobility assessment

Seating and mobility assessment is a highly complex process involving multiple component evaluations and tests.7 Seating and mobility assessments have many similarities to physical therapy and occupational therapy assessments but are more specific to the seating and wheeled mobility needs of the patient. The major difference in the outcome between more traditional therapy assessment and seating and mobility assessment is the intervention. The intervention plan in a seating and mobility assessment involves recommending a particular wheeled mobility device and adaptive seating system. As with any therapeutic intervention, the first step is an examination of the patient.8 This examination allows the therapist to collect all appropriate information to evaluate the patient’s needs and determine the most appropriate intervention plan.

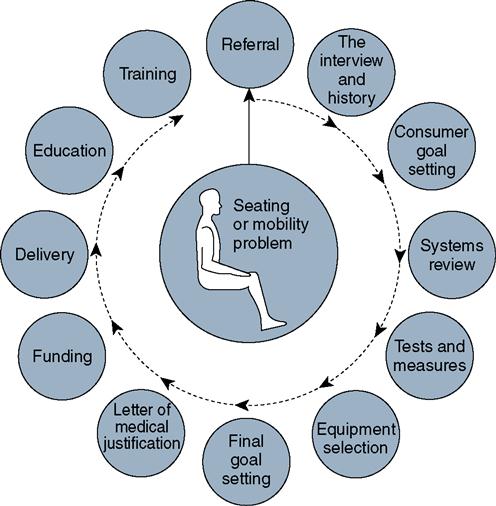

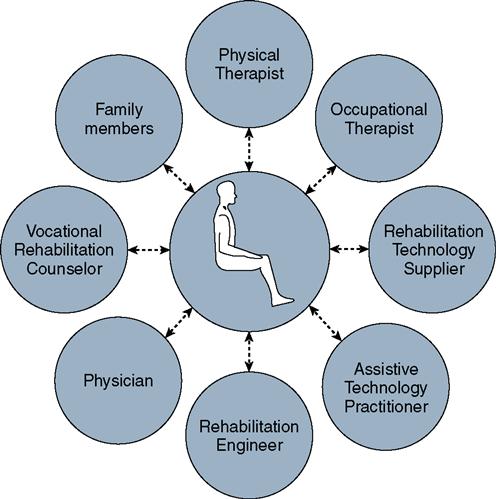

Members of the Assessment Team

Specially trained clinicians, organized in a team structure, are usually responsible for performing seating and mobility assessments (Figure 16-2). This team may consist of physical or occupational therapists with specialized training in wheelchair seating and mobility, physicians, rehabilitation technology suppliers, orthotists, and other health care professionals. The rehabilitation technology supplier is the team member who is ultimately responsible for providing the equipment to the patient. The rehabilitation technology supplier participates in the assessment process, compiles an equipment quotation and cost estimate, orders the equipment from the manufacturer, submits the justification and billing information to the equipment funding source(s), and then assembles the components in preparation for delivery of the wheeled mobility system. When an individual with seating or mobility problem is referred to the team, a multistep process of assessment, prescription, and training begins (Figure 16-3). The team must carefully document its findings and recommendations.

History

As with most therapeutic examinations, a detailed history is an essential component of a seating and mobility assessment. This history typically includes information related to diagnosis, nature of the disabling condition, related health problems, current and past assistive technology use, description of the home environment and other environments in which the equipment will be used, transportation needs of the patient, and funding source information for the equipment. All these elements are critical to the selection of an appropriate seating and wheeled mobility device.

The diagnosis of the patient is a critical component of the history—particularly diagnoses related to why years requires a wheeled mobility device. If a patient has a gait disability, the cause of the disability must be described both to evaluate the most effective intervention and to justify the need for the equipment to the funding source. Important questions to ask include the following:

In addition to the major diagnosis, information about associated health problems is also important. Related health problems may include breathing problems, cardiovascular or circulatory problems, seizure disorders, bowel and bladder continence problems, nutrition and digestion, medications the individual takes, surgeries in the past or planned surgeries, orthopedic concerns such as subluxation or dislocation of the hip or shoulder, osteoporosis, other orthotic interventions (including any leg or foot orthoses or trunk orthoses), skin condition problems or concerns, sensation, pain problems, visual deficits, hearing deficits, and cognitive and behavioral problems.9 Diagnostic information and related health concerns have a direct impact on the selection of appropriate equipment.

The history must also include elements related to the patient’s equipment use and the environmental demands. Gathering information about current and past assistive technology use is important. Knowing what the individual has tried and the outcomes of these interventions helps avoid the repetition of mistakes. Also, knowledge of previously used assistive technology is important for interfacing any new devices with already existing devices, such as alternative communication systems. Also, knowledge of the mode of transportation (e.g., car, adapted van, public transportation, school-provided transportation) is critical because equipment must be chosen to meet these transportation needs. The demands of the patient’s home environment or other environments in which the equipment will be used must be understood, including school or workplace environment and recreational activities.7 Last, but certainly not least, the funding source or sources for the equipment must be discerned. Different funding sources have different requirements for evidence documented in support of patient needs and benefits of selected devices and for medical necessity to justify reimbursement for the equipment.

Systems Review

Once this detailed history is gathered, the therapist may move on to a systems review.8 A systems review includes a limited examination of the major systems affecting the selection of the assistive device (Table 16-2), including the cardiovascular and pulmonary system, the integumentary system, the musculoskeletal system, the neuromuscular system, and the communication and cognitive abilities of the individual.8 During the systems review, additional questions may arise related to the history of the patient, particularly related to past equipment use; these questions should be incorporated into the remainder of the examination and the responses integrated with the history already recorded.

Table 16-2

Components of the Systems Review for Seating and Wheelchair Assessment

| Systems | Issues to Assess |

| Musculoskeletal | Range of motion Strength of all muscles Postural asymmetry Pelvic obliquity Pelvic rotation Pelvic tilt (anterior/posterior) Scoliosis Excessive kyphosis Lordosis Flexibility of any noted asymmetries |

| Integumentary | History of skin breakdown Surgeries performed Skin inspection to identify current problems Performance of active pressure reliefs Condition of pressure management equipment Success/failure of technologies in the past |

| Neurological | Motor control Abnormal muscle tone Abnormal primitive reflexes |

| Cardiovascular | Heart rate Blood pressure (at rest and with activity) Edema |

| Pulmonary | Respiratory rate Shortness of breath (dyspnea) Blood oxygenation (pulse oximetry) Change in pulmonary status with activity Change in pulmonary status with position |

| Communication | Verbal and nonverbal Use of alternative or augmentative systems Effectiveness of communication With family or familiar individuals With unknown or unfamiliar individuals |

| Cognitive status | Type of cognitive impairments present Developmental delay Progressive dementia Overall mental health and judgment Ability to learn Understanding of wheeled mobility function |

If an individual is already using a wheeled mobility device, the systems review must include an assessment of the patient’s use of the current equipment. The make and model of any devices currently used should be recorded, along with the sizes of all items and their present condition. In addition to the condition of the equipment, the patient’s posture and function while using this equipment should be noted. Determining why the person needs an assessment for new equipment is extremely important. Questions to ask include the following:

• Did the patient outgrow the equipment or did the equipment exceed its expected lifespan?

• Did the patient’s needs change because of a change in medical condition or functional status?

Specific details of how the current equipment is used and whether such use is appropriate and effective help with setting goals and determining the most effective equipment intervention for the future.

The reason for the seating and wheeled mobility assessment often translates into the justification for the recommended equipment, so this information is critical to ascertain during the examination. If the patient has not used any device in the past, why is one needed now? What change has triggered the referral for an evaluation? During this review, the specific, patient-centered, functional goals related to wheeled mobility device use also should be determined. These goals are incorporated into the intervention after all the data are collected and the evaluation is made.

Cardiovascular and pulmonary assessment, including blood pressure, heart rate, pulse oximetry, respiratory rate, and edema, are also important. Skin condition must be assessed, particularly overall seating contact areas. Gross musculoskeletal status should be assessed and the patient’s height and weight recorded. General assessments of function and movement ability in the current wheeled mobility system and the patient’s communication skills and abilities and cognition should also be performed.

Tests and Measures Used in Seating and Mobility Assessment

The systems review helps determine which areas require a more comprehensive assessment in the form of specific tests and measures, including seated and supine mat evaluation, seating simulation, equipment simulation, and pressure mapping (Table 16-3). If a patient has a cardiovascular condition, such as postural hypotension, then more extensive testing of different seated positions and interventions along with detailed tracking of changes in blood pressure are necessary during the mat evaluation and the seating simulation. Many tests and measures are used during the seating and wheeled mobility examination process. Some are necessary for all patients requiring adaptive seating, and some are used only in particular instances. Tests and measures for adaptive seating and mobility intervention can be classified according to postural and technical or instrumentation requirements, such as mat table or seat simulator.

Table 16-3

Tests and Measures Used in Seating and Wheelchair Assessment

| Component of Evaluation | Measures or Task Analysis |

| Seated mat evaluation | Unsupported seated posture Sitting balance Postural flexibility Functional abilities Transfers Reaching Activities of daily living simulation |

| Supine mat evaluation | Seating angles Thigh-to-trunk angle True hip flexion range of motion Thigh-to-lower leg angle Hamstring tightness Lower leg-to-foot angle Pelvic flexibility Abnormal muscle tone Mobility skills and abilities Supine to/from sitting transition |

| Mat (hand) simulation | Position of supports required Amount of force required Ability to reduce flexible asymmetries |

| Seated simulation testing | Desired seating dimensions Desired seating angles Seat tilt or orientation Seat to back angle support Need for biangular back support Other simulated supports and effects Lateral pelvic supports Lateral trunk supports Arm supports Leg and foot supports Head support |

| Equipment simulation | What equipment was used Results of mobility assessment in mock-up Consumer comfort Ability to meet goals with simulated system Photos to include with justification documents |

| Pressure mapping | Note cushions used during testing Results of cushions tested Pressure distribution patterns Consumer education Importance of proper seat cushion use Optimal pressure relief methods |

| Other | Custom molding simulation Pulse oximetry Circulatory testing Functional wheelchair propulsion testing |

Mat Evaluation

Many of the tests and measures used are incorporated into the mat evaluation, which consists of an evaluation with the patient in both seated and supine postures.7 During a seated mat evaluation, the therapist measures or determines a person’s unsupported seated posture, postural asymmetries, sitting balance, joint flexibility (particularly of the spine and pelvis) and functional abilities in terms of transfers and seated function, such as reaching ability. A supine mat evaluation is essential for measuring specific joint range of motion, strength, coordination, and abnormal muscle tone and reflexes. Particular attention must be paid to true hip joint mobility, orthopedic deformities such as pelvic asymmetries, hip joint subluxations or dislocations, and flexibility of spinal postures.7 The supine mat evaluation is critical in determining the flexibility of postural deformities because of the change in the effects of the gravitational pull on the body. If a postural deformity is present during the sitting assessment and then disappears during the supine mat evaluation, that deformity is “flexible” in nature and may be correctible in the adaptive seating system. If, on the other hand, the postural asymmetry is present in both seated and supine postures, in spite of any attempt at repositioning, then this asymmetry is described as a “fixed” posture.

Simulation Techniques and Equipment

The other tests and measures of a seating and mobility assessment are performed by using simulation techniques or equipment. Three primary simulation techniques are used: hand simulation, simulation with a commercial seated simulator, and simulation with commercial seating and mobility products similar to those likely to be selected.9,10

Hand simulation is often performed with the patient seated on the mat. During this simulation the therapist uses his or her hands to simulate or mimic forces applied by various components of an adaptive seating system. In this manner, the therapist can determine if external supports are capable of providing the desired effect on the patient’s posture and how much force is required or what is the optimal application point on the body.7

After hand simulation, a seating simulator may be used to verify the manual data. A seating simulator is a highly adjustable wheelchair frame with many interchangeable components.10 This device is first preset to provide the desired supports; then the patient sits in it so the therapist can determine if the settings actually produce the desired postural or functional outcomes.

The third simulation method involves assembling actual commercial products into a system similar to that being recommended to assess its effect. This may be done if a commercial simulator is not available as an additional component after performing the other types of simulation. This final simulation provides evidence of the effectiveness of actual products in meeting the desired goals of the seating and mobility assessment and may be an excellent way of providing the funding source with information regarding why specific equipment is being recommended.

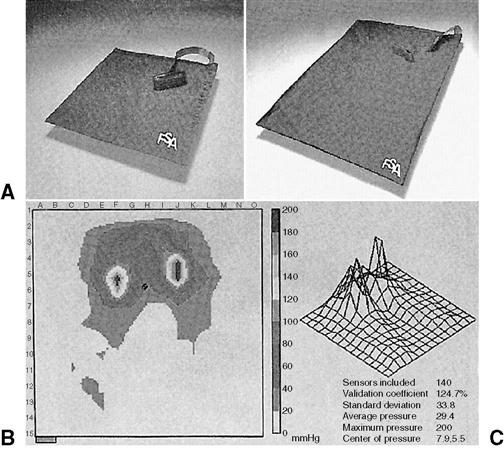

Other tests and measures used for seating and mobility assessment include pressure mapping (Figure 16-4),11 custom contour seat simulation, pulse oximetry during simulation, specific circulatory assessments during simulation, and functional wheelchair propulsion testing.12 These specific measures may not be used in all seating and mobility assessments but can be mixed and matched according to the needs of the patient. All these tests and measures provide the therapist with necessary information required for evaluation and determination of final equipment selections.

Plan of Care and Equipment Prescription

The evaluation of all this information will lead to a diagnosis related to the patient’s level of function and a plan to address specific adaptive seating and wheeled mobility device needs that have been identified (Table 16-4). The clinician and patient also set specific goals for use of the equipment within various environments. The actual intervention process in seating and wheeled mobility is often called the equipment recommendation or equipment prescription. During this process a specific mobility base is selected and adaptive seating equipment is specified.

Table 16-4

Components Included in Final Recommendations

| Category | Details |

| Wheelchair propulsion ability | Distance Speed Safety In recommended wheelchair In less expensive options |

| Final equipment selection | Mobility base Access method Postural support components |

| Goals of the seating system | Based on consumer’s stated goals Objective Measurable Related to recommended equipment |

| Wheelchair and seating fitting and delivery needs | Is preliminary fitting required? How many visits will be necessary? Estimated time to delivery |

| Training and education plans | When will the training begin? Who will carry out the training? Referral for additional training? Written materials to be provided Product manuals Care and maintenance instructions Safety recommendations and concerns Guidelines for proper and effective use |

| Plan for follow-up care | When will follow-up occur? Scheduled visits or as needed? Frequency of reevaluation? |

Other major components of adaptive seating and mobility intervention involve coordination, communication, and documentation. The physical or occupational therapist typically has the primary responsibility of coordinating the seating team and assuring that all team members are working together to assist in the attainment of the patient’s goals. Communication with all team members is essential during this process. All team members must be made aware of the results of the examination and the ultimate goals involved. Each team member may have some responsibilities in this process; the rehabilitation technology supplier, for example, has a primary responsibility to provide specific manufacturer’s specifications for the equipment needed. These specifications will then be used to prepare the letter of medical justification. In addition to all the typical documentation of the history and physical assessment, the therapist also has a primary responsibility, in the case of adaptive seating intervention, to prepare the letter of medical justification. The letter is critical because it is the primary means of communication with all funding sources involved to obtain necessary funding for the seating and wheeled mobility system.

Documentation: The Letter of Medical Justification

The intention of the letter of medical justification is to provide the funding source with a clear picture of the patient with a disability and the equipment being recommended, with a focus on why the specific equipment being prescribed is required. This letter must contain several elements. The introductory paragraph should describe the person with a disability. This description includes the diagnoses, onset dates, prognosis, and a summary of the history and the systems review.

Next, detailed information is provided about the specific tests and measures used during the examination and outcomes of the evaluation. These include, but are not limited to, the individual’s functional status, strength, range of motion, orthopedic deformities, motor coordination, abnormal tone or reflex findings, and the results of the equipment simulation. This information can be organized and reported on a standardized form or in a narrative style.

Specific measurable, functional goals for the adaptive seating and wheeled mobility system should be clearly stated. All the specifications of the selected equipment must be included, and the reason for each item must be effectively justified as to why the person requires this specific piece of equipment (Box 16-1). The funding source sometimes also requires a description of other possible lower cost options and an explanation of why these options are not effective for the patient. Finally, a summary of the patient information and contact information for the primary therapist and the prescribing physician should be provided so that the funding source may contact these individuals if any questions arise during the review process.

Meticulous preparation of the letter of medical justification may mean the difference between efficient funding of the seating and mobility system and a long, drawn-out review process that may delay the delivery of equipment by several months.

When the Seating and Mobility System Is Delivered

After approval by the funding source and after the adaptive seating equipment is ordered and obtained, the rehabilitation technology supplier notifies the therapist that the seating and mobility system is ready for delivery. The patient then returns to the seating clinic and the adaptive seating and mobility device is delivered and adjusted to ensure proper fit and efficient function. Delivery of the wheelchair or seating system is a critical element in the intervention process and directly affects the outcomes related to use of the equipment.

Delivery of equipment typically occurs several months after the examination and prescription process. The therapist is responsible for ensuring that the status and needs of the patient have not changed since the initial seating and mobility assessment. If the needs have changed, then recommended modifications to the equipment must be specified at this time. The equipment must then be verified to ensure it meets all the recommended specifications. Finally, the equipment must be adjusted for proper fit and the patient must be trained in its safe use, adjustment, maintenance, and care.

The patient should have the opportunity to function in and use the equipment during the initial delivery to ensure that the goals set during the examination can be effectively attained. This may require a period of training and further rehabilitation intervention as an outpatient or in the patient’s living environment. In addition, the patient and caregivers are instructed in routine maintenance and cleaning of the equipment, by verbal instruction, demonstration, and in written format, such as review of the owner’s manuals provided by the equipment manufacturers. The patient and caregivers also need to learn when they should return to the clinic for adjustment or modification of the equipment.

Assessment of Seating and Mobility Outcomes

The final critical component of an adaptive seating evaluation is reexamination, or followup and follow-along. Adaptive seating equipment needs are fluid over time. Fixed orthopedic deformities may change or progress, and functional abilities often change. Equipment needs must be reevaluated when the patient’s needs are no longer met by the equipment. This may happen as equipment ages and falls into disrepair, or as the patient’s functional or physical status changes over time. Most adaptive seating equipment has a usable life span of 3 to 5 years. If a person is particularly active or if the equipment is used in harsh and demanding environments, the equipment may have a shorter functional life span. Periodic reexamination of equipment and patient needs is essential to maintain optimal function. Although planning reexamination appointments is important, the patient needs to understand when and why contacting the therapist and requesting a reexamination between scheduled visits might be necessary. The patient is the most knowledgeable person regarding the adequacy of the equipment and whether goals are being met.

Biomechanical principles in seating and mobility

Adaptive seating for persons who use wheelchairs involves the strategic application of forces to provide postural support and stability for optimal function. All applications of forces in this context are governed by the laws of physics and described in the field of biomechanics, the study of body position and movement.5 All adaptive seating components exert forces or torques on the body that ultimately affect changes in posture and static or dynamic equilibrium. Improperly applied forces or improper fit of components can lead to a variety of seating and mobility problems. Table 16-5 summarizes the most commonly encountered problems.

Table 16-5

Potential Problems Resulting from Improper Biomechanics in Support or Propulsion

| Support or Access Problem | Possible Resultant Biomechanical Problem | Potential Equipment Solutions |

| Seat too long | Posterior pelvic tilt Sliding out of wheelchair | Shorten seat or provide additional back support (effectively shortening seat) |

| Seat too short | Pressure ulcer, lack of support under femurs Sliding out of seat | Increase seat depth of wheelchair or add longer seat cushion with solid support underneath |

| Seat too wide | Lateral shift of pelvis in chair Pelvic obliquity Trunk scoliosis Feeling of instability | Narrow wheelchair seat or add lateral pelvic supports to properly center pelvis in wheelchair |

| Seat too narrow | Pressure ulcers over greater trochanters Difficulty transferring in and out of wheelchair | Widen wheelchair seat |

| Back too wide | Flexible scoliosis Lateral trunk leaning Pelvic obliquity Feeling of instability | Narrower back support Lateral thoracic supports Lateral pelvic supports |

| Back too narrow | Lack of movement needed for function Skin breakdown on lateral trunk Discomfort caused by inability to move | Widen wheelchair back support |

| Back too low | Upper trunk instability; limited function Excessive thoracic kyphosis Posterior pelvic tilt | Higher back support Solid back support (if current back is sling) |

| Back too high | Falling forward in wheelchair Inability to propel wheelchair optimally | Lower back height Narrower upper back support to allow increased scapular excursion |

| Rear wheels too far back | Shoulder pain; impingement Inability to optimally propel wheelchair | Move rear wheels forward |

| Rear wheels too far forward | Wheelchair tipping backwards; user unable to control | Move rear wheels back on frame |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree