Acute Repair of the Achilles Tendon Rupture: Open and Limited Open

Eric M. Bluman

Christopher Chiodo

Jason Calhoun

Acute Achilles tendon ruptures usually occur in less-active, male patients between the ages of 30 and 50 years while they are engaged in an occasional sporting activity. Although many etiologies have been suggested as predisposing factors, some suggest that decreased vascularity of the tendon places it at risk for rupture. Relatively minor injury from an abrupt push-off or sudden fall may cause an acute contracture of the powerful triceps surae muscle complex or forced dorsiflexion of the ankle that can cause a rupture. Rupture may also occur in “weekend” athletes during high-demand sporting activities such as tennis or basketball. Some surgeons believe that acute rupture is preceded by peritendinitis or tendinosis and is caused by a combination of mechanical factors and tendon degeneration.

The diagnosis of an acute rupture of the Achilles tendon is usually made by a history of a pop or snap in the posterior aspect of the ankle along with acute onset of pain. Physical examination reveals a swollen, painful ankle with ecchymosis posteriorly. Swelling and hematoma within the paratenon may obscure a palpable gap within the tendon itself, but tenderness is generally present. Many patients can still actively plantarflex the ankle against mild resistance because of the pull of the posterior tibial tendon and the long flexor tendons. Inability to rise onto the toes or a heel resistance test, performed by grasping the heel and resisting plantarflexion, showing absence of plantarflexion power, is consistent with an Achilles tendon rupture. The Thompson test has proved to be a reliable indicator of Achilles tendon rupture (1). During this test, the calf muscle is squeezed with the patient prone and the feet extending over the end of the examination table. If the tendon is intact, the foot can plantarflex. If it is ruptured, the foot cannot move much or at all (Fig. 43.1). This is diagnostic of Achilles tendon rupture. There are proponents of both open and closed treatment of acute tendon ruptures; many today favor operative management in the acute setting. Proponents of open treatment cite factors such as the lower rerupture rates, greater strength, and greater endurance after open treatment. In older or lower-demand patients, nonoperative treatment may be appropriate (2, 3, 4 and 5). Open surgical treatment is generally advised for younger or more active patients (6).

Minimally invasive repair of the Achilles tendon encompasses a small set of techniques that have been developed to avoid the complications associated with large incisions required for standard open repairs. Both limited open and percutaneous techniques are considered minimally invasive. Limited open techniques utilize small incisions that allow direct visualization for approximation

and fixation of the tendon ends. Percutaneous techniques may or may not use small incisions to pass fixation sutures but do not allow for direct visualization of the ruptured tendon ends. Limited open techniques are described here.

and fixation of the tendon ends. Percutaneous techniques may or may not use small incisions to pass fixation sutures but do not allow for direct visualization of the ruptured tendon ends. Limited open techniques are described here.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The general health of the patient and any associated systemic diseases may influence the decision process regarding open versus closed treatment. Frank discussion of the risk and benefits of closed and open treatments should be undertaken with the patient, and an informed mutual decision about treatment should be reached. The main indication for surgery is acute tendon rupture. The operation can be considered in selected patients with well-controlled diabetes mellitus, patients undergoing anticoagulation therapy, and nicotine users, recognizing that the patients will need to accept the risk of problems such as delayed wound healing.

Contraindications to surgical care are usually associated with wound healing. Systemic cortisone and methotrexate, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and vascular compromise of the lower extremity are relative contraindications to open surgical treatment. The open repair technique may be preferred over the limited open method for chronic ruptures (those older than 4 weeks) with a large gap, complex tears with excessively frayed tendon ends, very distal or very proximal ruptures (7). Nonoperative management may be preferred for noncompliant patients, and older, sedentary patients.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

If operative treatment is planned, the foot should be maintained in a compressive Jones-type dressing in mild plantarflexion before surgery. This prevents the formation of fracture blisters and diminishes swelling, which can otherwise compromise wound healing.

Ruptures may occur at the myotendinous junction but more commonly in the midsubstance of the tendon. Avulsion off of the calcaneal insertion may also occur. The level of rupture can usually be determined by physical examination through the identification of the level of the gap within the substance of the tendon. Plain lateral radiographs may reveal a defect in the shadow of the Achilles tendon, and the triangular lucency of the fat pad anterior to the Achilles tendon is generally obliterated. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also confirm the level and the extent of rupture. However, the diagnosis of rupture is generally based on clinical examination, and MRI, although instructional for educational purposes, should be reserved for when the diagnosis is in doubt.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Technique 1: Open Repair of Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture

The patient is placed in a prone position, with axillary rolls under the chest and adequate padding of the upper extremities to avoid any possible neurovascular injury during surgery. General or spinal anesthesia is satisfactory. A pneumatic tourniquet is applied at the level of the thigh on the affected extremity, which is then prepped and draped in sterile fashion.

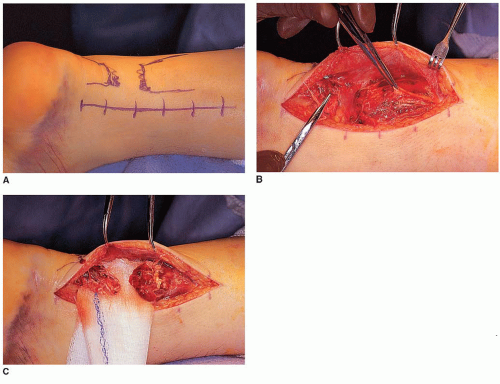

After the blood is evacuated with an Esmarch wrap, the tourniquet is inflated. The incision is made along the posteromedial aspect of the leg, starting just above the level of the myotendinous

junction and extending to the level of the tendinous insertion on the calcaneus (Fig. 43.2A). When avulsion of the tendon from its calcaneal insertion is suspected, the incision is extended distally for better exposure.

The incision is deepened to the level of the paratenon. The paratenon is then opened to expose the Achilles tendon (Fig. 43.2B). The Achilles tendon is not covered by a tendon sheath, but by a paratenon composed of areolar connective tissue and elastic fibers. During surgical repair, the tendon should be exposed to the layer of the paratenon. The paratenon should be reflected as part of the full-thickness flap with the overlying subcutaneous tissue and skin to avoid disruption of the vascular supply to the skin.

The sural nerve perforates the crural fascia at the myotendinous junction and passes subcutaneously distally on the lateral aspect of the Achilles tendon. A medial incision avoids injury to this nerve. It also allows easier access to the plantaris tendon, which, if present, passes deep to the crural fascia along the medial aspect of the Achilles tendon. The plantaris may be used to augment primary surgical repair of the tendon.

If the plantaris tendon is present, it is easily identified within the substance of the wound. Inspection of the level of the rupture is performed. Hematoma is removed with irrigation and a curette.

Ruptures are generally mop-handle-type tears (Fig. 43.2B), which prevent easy repair.

A tear at the level of the myotendinous junction is often difficult to repair because of inadequate purchase of suture material into the proximal tissues. Lindholm technique can be modified to allow repair with turn-down flaps. Rather than inverted tendon strips being raised from the proximal portion of the tendon and reflected distally, the tendon strips are raised from the long distal portion of the tendon and inverted proximally. These strips can be woven into place to allow continuity of tendon material to augment the repair. Primary suturing of the tendon is carried out in an identical fashion to that for midsubstance tendon ruptures as described below.

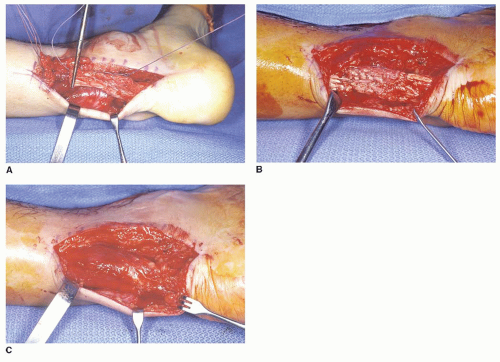

For a midsubstance tear of the Achilles tendon, after debridement of the tendon edges, a heavy, nonabsorbable suture is placed using a modified Krackow (Fig. 43.3A and B), triple bundle (Fig. 43.3C), or Bunnell technique in the proximal stump.

FIGURE 43.3 A: Insertion of stitches for repair of an acute rupture with a Krackow-type stitch. B: Completed repair. C: Triple bundle technique.

A second suture is placed in the distal stump (Fig. 43.4A). The knee is then flexed, and the foot is plantarflexed, allowing the ends of the suture to be tied without tension (Fig. 43.4B). The repair is then augmented using an absorbable suture in a vertical circumferential stitch.

The wound is then copiously irrigated and the edges of the paratenon approximated (Fig. 43.4C).

The paratenon is then closed with a 3-0 absorbable suture. Paratenon closure prevents scarring of the tendon to the overlying soft tissues and skin.

The skin is closed with an interrupted 3-0 nylon skin stitch. The foot should be in plantarflexion, so the repair is not under tension, while the paratenon and overlying skin are closed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree