Achilles Tendon Trauma

Alan Ng

Keith L. Jacobson

In 1541, Paré was given credit for recognizing Achilles tendon ruptures as a clinical entity. It was not reported in the literature until 1633 (1). It was not until the 1920s that Abrahamsen (2) and Quénu (3) advocated surgical repair. Since the 1920s, surgical management has been the preferred choice of treatment. Surgical repair has been advocated because it consistently affords for greater strength, endurance, and power, with less incidence of rerupture, as compared with nonsurgical management (4,5,6,7,8 and 9).

Ruptures of the Achilles tendon often occur between the third and fifth decades of life. There has always been a male predilection. This injury is often associated with an athletic activity in individuals who generally lead sedentary lifestyles. We often refer to these individuals as “weekend warriors.”

Most Achilles ruptures occur within an area roughly 2 to 6 cm from the insertion. We know that the fibers of the Achilles tendon do not course straight down but actually rotate from medial to lateral in a spiral fashion. The maximal twist is reached about 2 to 6 cm from the insertion. Within this 2 to 6 cm area is also a zone of hypovascularity, as described, in 1958, by Lagergren and Lindholm (10). This defined area is also commonly referred to as the “watershed area.”

There are several physiologic factors that are thought to contribute to the two common theories of Achilles tendon ruptures. The mechanical stress theory leading to Achilles rupture, as popularized by Inglis and Sculco (11), described the malfunction of the inhibitory mechanism within the muscle, which normally prevents excessive tension and monitors forces during sudden muscle overload. Nonetheless, this explanation has been generally dismissed as not credible. However, there are three types of indirect trauma, described by Arner and Lindholm (12), which are thought to cause ruptures. They include a direct push-off from a weight-bearing forefoot and an extended knee; sudden dorsiflexion of the ankle, such as slipping on a stair or ladder; and violent dorsiflexion of a plantarflexed foot that occurs when jumping or falling from a height and landing with the foot plantarflexed.

The degenerative theory (13,14) describes a hypovascular tendon exposed to repetitive trauma, resulting in local degenerative changes within the midsubstance of the tendon. This weakened state, of the tendon, predisposes it to rupture after an excessive load is applied.

There are other external factors, which have also been shown to contribute to Achilles tendon ruptures. They include systemic (15) and local steroids (16), blood type O (17), genetics (18), renal insufficiency (19), arteriosclerosis (20), hyperlipidemia (21), gout (21), hypothyroidism (21), rheumatoid arthritis (21), and fluoroquinolones (21).

When surgically addressing Achilles tendon ruptures, it is important to understand not only the theoretical causes of rupture but also the systemic and external factors that may influence your approach to treatment.

EVALUATION/DIAGNOSIS/FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients will present complaining of weakness at the ankle and will often state that they felt that an object struck them. The injury is usually only painful at the time the rupture occurs and is not significantly painful upon presentation to the office. The observed gait pattern is often abducted and antalgic.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

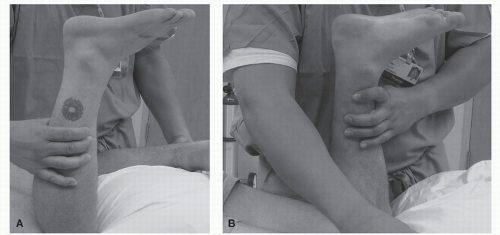

Upon initial examination, there will often be a visual deficit also known as the “hatchet strike defect.” This defect is a visible dell in the posterior ankle compared with the contralateral side. A palpable deficit in the Achilles tendon is also identified upon examination (Fig. 101.1).

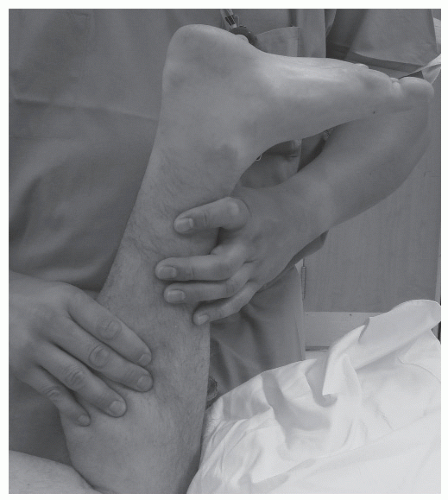

There are multiple exams described to assess the integrity of the Achilles tendon. Thompson test is performed by placing the patient prone and flexing the leg. With the leg flexed, perform side-to-side compression of the calf; if the tendon is ruptured, there will be no plantarflexion visualized (22). If no motion is noted, the test is positive. In some cases, there can be false negative exam. This is seen when the plantaris tendon is intact, resulting in residual plantarflexion (Fig. 101.2).

The resting plantarflexion exam is performed when the patient is prone and the knee and leg are flexed at 90 degrees. If the Achilles tendon is ruptured, the foot will be visualized resting at 90 degrees or less. The nonaffected foot will be slightly plantarflexed due to the intact Achilles tendon (23) (Fig. 101.3).

The needle exam is another way to assess if the Achilles tendon is intact. This is accomplished by having the patient prone and placing a needle in the gastrocnemius-soleus muscle belly above the perceived rupture site. With the needle in place, plantarflexion of the foot is performed. If the Achilles is intact, the needle will move upon plantarflexion of the foot. If the Achilles is ruptured, the needle will not move upon plantarflexion of the foot (24).

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Advanced imaging can also be used to assess a complete rupture or to assess the amount of deficit noted between the ruptured ends. The use of diagnostic imaging is primarily a physician’s choice; oftentimes advanced imaging is not needed if clinical examination is definitive for the rupture. If delay in treatment occurs, advanced imaging can be useful for assessing the amount of tendon retraction and the resultant deficit that needs to be repaired.

Radiographs are not necessary unless there is a suspicion of an avulsion fracture off the posterior calcaneus.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

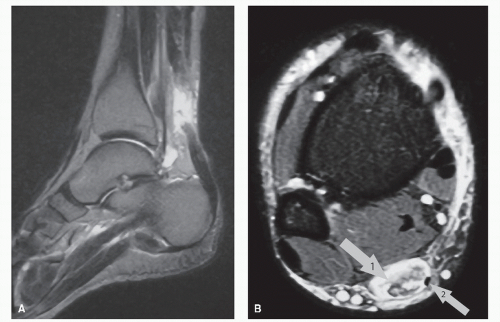

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be utilized to assess the amount of deficit created from the rupture (Fig. 101.4).

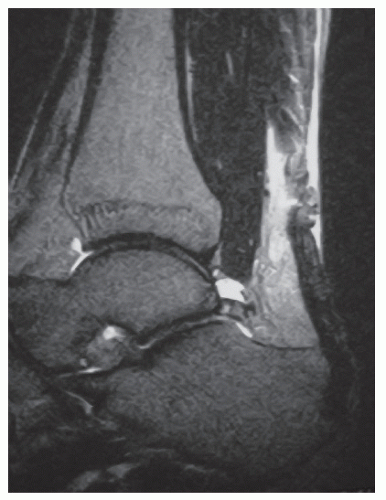

If the clinical exam is in nondefinitive, MRI can help determine if there is a complete or partial rupture. False negative exams can also occur with MRIs. After rupturing, the tendon may lay back down into its anatomic position. This can give the appearance of a partial tear, when in fact it is completely ruptured (Fig. 101.5).

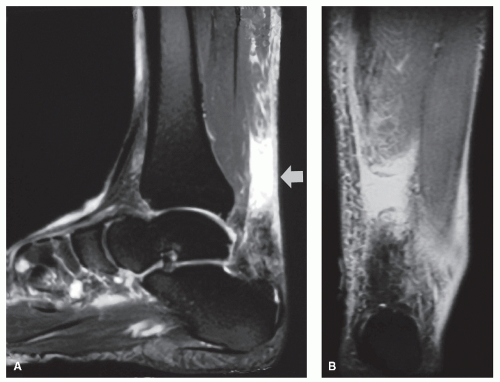

When addressing chronic ruptures, MRIs are very helpful in determining the amount of deficit present, essentially assisting in presurgical planning (Fig. 101.6).

ULTRASOUND

Ultrasound can be used to image the Achilles trauma. It has been used to assess acute and chronic injuries. Ultrasound may give false negative results in acute injuries due to the hematoma filling the deficit. Astrom et al (25) compared ultrasonography and MRI in assessing chronic Achilles tendinopathy with regard to the nature and severity of the lesion. In 27 histologically verified cases, ultrasonography was positive in 21 and MRI was positive in 26 of 27 cases.

Figure 101.2 Positive Thompson-Doherty exam. Note the leg flexed with patient in prone position and lack of plantarflexion upon compression of the calf. |

The majority of Achilles tendon ruptures can be diagnosed clinically. If there is any question of deficit, complete rupture, or level of rupture, advanced imaging may be appropriate to verify the diagnosis or to assist in surgical planning.

TREATMENT OF ACUTE RUPTURES

In the past, there has been controversy regarding treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures with surgical intervention or cast immobilization. Current literature and studies show a much better result and decreased rerupture rate in surgically repaired Achilles tendons (26,27,28 and 29). Also, the postoperative recovery time for surgically repaired tendons is typically less than nonsurgically treated ruptures. The problem often associated with casted repairs relates to the tendon functionally lengthens due to the scar tissue forming the bridge between the two ruptured ends. This creates a significant loss of strength and loss of the length/tension relationship. Surgical repair has become more favorable with new stronger repair products and better repair techniques allowing earlier mobilization and faster return to activity. Nonoperative care is usually reserved for those patients who are not surgical candidates because of local or systemic contraindications. Patients with severe immunocompromised status, elderly, low-demand patients, vascular compromised patients, and patients that are at risk for compliance are also candidates for nonsurgical care. Patients should be surgically repaired in the acute setting if they do not fall into the above stated categories.

NONSURGICAL TREATMENT

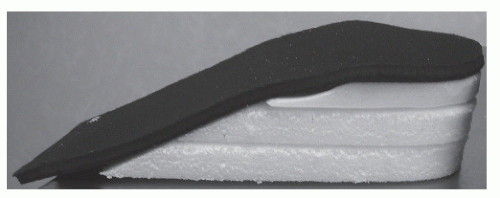

Proponents of conservative treatments have all preferred immobilization, but the type, position, and duration of immobilization has been variable. The majority of the literature advocates immobilization for a minimum of 8 to 12 weeks. The controversy involves non-weight-bearing versus weight-bearing, casting above or below the knee, and position of the extremity (30,31,32 and 33). The authors’ preference for nonsurgical treatment involves placing the patient in an “Achilles boot,” which is a CAM walker with special sequential heel wedges and maintaining the patient non-weight-bearing for 3 to 4 weeks. This is followed by progressive weight-bearing in the Achilles boot for

another 2 to 3 weeks with progression to normal shoes with a heel wedge for another 2 months (Fig. 101.7).

another 2 to 3 weeks with progression to normal shoes with a heel wedge for another 2 months (Fig. 101.7).

SURGICAL EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Timing of surgery in treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures does play a role in postsurgical recovery. The ideal repair time is within the first 7 to 14 days. This is based on the fact that we know the greatest amount of vascularity to the injured site occurs in that period of time (34). This is consistent with the principals of wound healing. After the first 7 to 14 days, the injury is no longer in the inflammatory stage of healing and the vascularity to the injury decreases. Surgical repair during the first 7 to 10 days is more difficult due to the amount of fraying and “mop ending” of the tendon interface. After the first 14 days, the tendon ends remodel allowing for easier end-to-end repair at the sacrifice of optimal vascularity. Surgical repair becomes even more challenging when the Achilles tendon enters the remodeling phase of healing. The tendon ends become increasingly avascular resulting in a chronic rupture. When the rupture becomes chronic, advancement techniques and or tendon transfer techniques must be utilized to repair the tendon injury.

Figure 101.7 Achilles tendon wedges. Placement in any type of fracture boot or CAM walker to force plantarflexion. |

Although repair is easiest when the tendon ends have consolidated, optimal vascularity is seen in the first 7 to 14 days and is the ideal time for surgical repair. When the tendon is repaired in this time span, faster healing occurs allowing for increased confidence in aggressive rehabilitation protocols postsurgically (Fig. 101.8).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

There are multiple described tendon repair techniques in treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures. The basis of these repair techniques involves allowing end-to-end apposition of the two ruptured ends of the Achilles tendon. Three main suture techniques have been utilized with excellent results: the Bunnell, Kessler, and Krackow suture techniques. Watson et al (35) tested these techniques in cadavers and found that all techniques ultimately demonstrated failure at the repair site.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree