Achilles Tendon Lengthening

Jeremy M. LaMothe

David S. Levine

DEFINITION

A plantarflexion contracture is defined as the inability to passively dorsiflex the ankle at least 5 degrees past neutral, with a neutral hindfoot, and suggests contracture of the gastrocsoleus complex (FIG 1).

Plantarflexion contracture may be secondary to contracture of the gastrocnemius, soleus, or both components of the complex.

Plantarflexion contractures are commonly associated with a variety of foot/ankle conditions. Up to 65% patients presenting with foot and ankle pathology may have some degree of contracture of the gastrocsoleus complex.2

ANATOMY

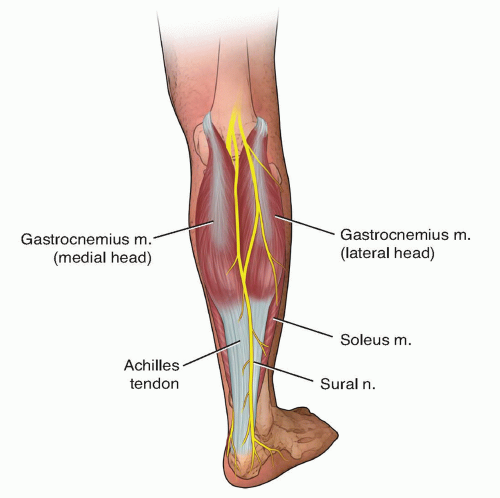

The superficial posterior compartment contains the gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris muscles.

The gastrocnemius muscle has two heads (medial and lateral) and originates above the knee from the posterior distal femur, which makes the gastrocnemius a three-joint muscle.

The soleus originates from the posterior aspect of the proximal fibula, interosseous membrane, and the posterior aspect of the middle third of the tibia, which makes the soleus a two-joint muscle.

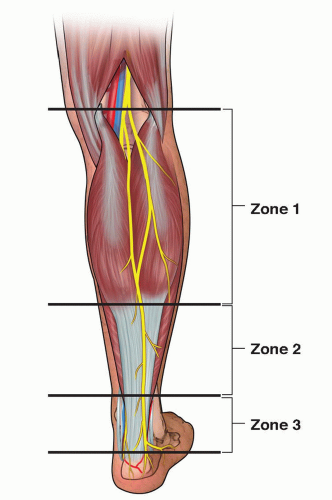

FIG 1 • The gastrocsoleus complex, as viewed from a posterolateral angle, including the location of the sural nerve.

The gastrocnemius tendon is longer than that of the soleus and they blend together to form the Achilles tendon approximately 5 cm from the calcaneal tuberosity, which has a broad enthesis.

As the Achilles tendon shifts from its origin to insertion, it spirals 90 degrees so that the medial border of the proximal tendon rests posterolaterally.

Zone 1 is from the femoral origins of the gastrocnemius muscle to the distal extent of the bluntly separable interval between the gastrocnemius and soleus, which is usually at the level of the medial gastrocnemius muscle belly.

Zone 2 is from the distal aspect of the medial gastrocnemius muscle belly to the distal end of the soleus muscle.

Zone 3 is the Achilles tendon from the distal end of the soleus muscle to the insertion on the calcaneus.

The gastrocnemius and soleus muscles can be differentially lengthened in zones 1 and 2 (ie, separate fascial releases can be performed for each of these muscles).

PATHOGENESIS

The etiology of gastrocsoleus contractures is broad and includes metabolic/endocrine (eg, diabetes mellitus), posttraumatic, congenital, neurologic, and idiopathic origins. The natural history of the contracture is dependent on the etiology.

Gastrocsoleus contractures have implications for coronal and sagittal plane pathologies.

Sagittal plane pathologies include forefoot overloading and its sequelae including metatarsalgia, plantar plate pathology, or bunions.

Coronal plane pathologies include flatfoot and hallux valgus deformities.

Contracture may also be associated with midfoot pain/arthritis, planar fasciitis, or Achilles tendinopathy.

In patients with peripheral vascular disease and/or neuropathy, contracture may predispose to Charcot midfoot breakdown or serious foot ulcerations; treatment may require a gastrocsoleus complex lengthening.

NATURAL HISTORY

In general, conditions caused by a gastrocsoleus complex contracture will fail to completely resolve without some form of gastrocsoleus stretching/lengthening. This concept can be critical in diabetic forefoot ulcers.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The patient history should be used to determine if there is a specific etiology of the contracture (eg, posttraumatic, diabetes, cerebral palsy, stroke).

Associated medical conditions should be ascertained on history (eg, diabetes, neuropathy).

Physical examination should assess the overall lower extremity alignment, including hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot alignment.

Look for any signs of forefoot overloading, such as metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint tenderness, prominent metatarsal calluses, or ulcerations.

Special attention should be paid to ankle range of motion with the knee extended and flexed, with the hindfoot held in a neutral position as is described with the Silfverskiöld test (see Exam Table at end of volume), which may help distinguish an isolated gasctocnemius contracture from a tight gastrocsoleus complex.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Standard radiographic workup should include a weightbearing foot and ankle series.

Radiographs should be assessed for foot alignment and any structural causes for decreased ankle dorsiflexion (eg, talar neck/anterior tibial osteophytes, malunion, inflammatory ankle arthritis; FIG 3).

Targeted imaging should be performed for the symptoms the patient is experiencing (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] for Achilles tendinopathy).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Ankle arthritis

Anterior ankle impingement (bony or soft tissue)

Posttraumatic malunion of the tibia

Syndesmotic malreduction

Neglected drop foot

Spasticity

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Calf stretching is indicated in patients with a gastrocsoleus contracture and foot symptoms/pathology that can be attributed to or exacerbated by this contracture.

Static calf stretching may provide small increases in ankle dorsiflexion.7

Eccentric calf stretching exercises may be helpful in managing Achilles tendinopathy.1

Night splints may be indicated in the treatment of plantar fasciitis, but the effectiveness of night splints in treating other conditions is unknown.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Failure of nonoperative management of the pathology associated with a tight gastrocsoleus complex is an indication for surgery.

Lengthening of the gastrocsoleus complex can be a critical component of a more extensive surgical plan (eg, Achilles tendon lengthening in addition to a flatfoot reconstruction) or it may be the sole treatment (eg, gastrocnemius recession in patients with noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy). Accordingly, surgical decision making is individualized for each patient.

Different techniques for gastrocsoleus lengthenings and their relative characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Preoperative Planning

The patient should be medically optimized for surgery; this is of particular importance in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Deformities of the lower extremity should be examined, and joint ranges of motion should be measured.

Preoperative performance of a Silfverskiöld test is of critical importance to determine if the plantarflexion contracture is secondary to an isolated gastrocnemius contracture or a combined gastrocsoleus contracture.

If gastrocsoleus lengthening is indicated as part of a larger surgical plan, it is controversial if the lengthening should be performed at the beginning or the end of the case.

Positioning

Although positioning is determined by the specific surgical case, supine positioning is generally sufficient to perform most gastrocsoleus lengthenings.

An assistant can elevate the leg to facilitate lengthenings, such as the Hoke or Vulpius lengthening (FIG 4).

Prone positioning is preferred for an Achilles Z-lengthening.

Occasionally, concomitant procedures may require repositioning.

Table 1 Different Techniques for Gastrocsoleus Lengthenings and Their Relative Characteristics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree