Achilles Tendon Disorders

James L. Thomas

The Achilles tendon is the largest and strongest tendon found in humans (1). Due to its size and strength, as well as the fact that the gastrocnemius-soleus (triceps surae) complex is the largest of the calf muscles, the Achilles tendon may be involved in a wide variety of disorders. Additional factors to consider when looking at etiologies of pathology in this area include the morphology of the posterior calcaneus and the somewhat unique blood supply of the Achilles tendon itself.

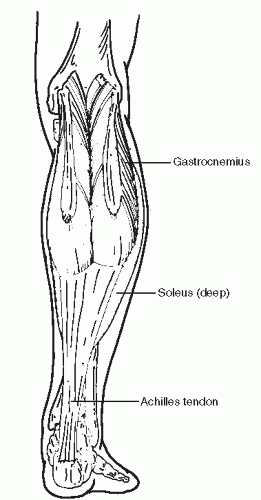

The Achilles tendon is the tendinous extension of the gastrocnemius-soleus muscular complex (Fig. 78.1). The gastrocnemius originates from the posterior femoral condyles and crosses the knee, ankle, and subtalar joints. The soleus has its origins from the interosseous membrane as well as the posterior tibia and fibula and crosses only the ankle and subtalar joints. The plantaris tendon originates from the lateral supracondylar line and inserts medially on the calcaneus. It may also be a part of the Achilles complex. A few centimeters before its insertion, the Achilles tendon fibers twist approximately 90 degrees, with the medial fibers rotating to a more posterior position. Secondary to this rotation, the contribution of the soleus is more medially located and the gastrocnemius contribution is more laterally located. The tendon then inserts primarily into the middle third of the posterior calcaneus where it is associated with the retrocalcaneal bursa, located between tendon and bone. The Achilles tendon bursa, located between skin and tendon, may also be present. Posteriorly, the calcaneus itself is quite broad and may be slightly anteriorly angulated at the proximal third of the posterior surface. Although the musculotendinous junction, insertion site, and peritenon provide blood supply to the tendon, a zone of relative avascularity of the tendon has been identified 2 to 6 cm proximal to its insertion on the calcaneus (2,3). An area of decrease in blood supply at the insertion of the Achilles tendon on the calcaneus has also been identified (4). These areas of diminished blood supply make the distal Achilles tendon particularly vulnerable to injury.

The gastrocnemius-soleus complex is very active and is possibly the main contributor to propulsive force in walking as well as jumping and running through concentric contracture, although eccentric lengthening also occurs. This is particularly illustrated by the fact that forces approximating almost 10 times body weight and up to 7,000 N are transmitted through the tendon with running (5,6 and 7). There are many different anatomical and biomechanical variations of the foot and ankle that also contribute to producing pathology of the Achilles tendon, especially close to its insertional site. Traumatic, inflammatory, and degenerative disorders may result.

Various names and terminology have been utilized in describing pathology of the Achilles tendon and its insertional area. Among these, the terms “tendinitis” and “tenosynovitis” are often used. However, these are somewhat inaccurate anatomic terminologies when describing pathology in this area. Very little inflammatory changes of the tendon itself are actually seen in symptomatic individuals, although surrounding structures may exhibit significant inflammation (i.e., bursitis, paratenonitis) (8). Also, the term tenosynovitis does not truly apply here as the Achilles tendon is covered by paratenon and not a synovial sheath. Tendinosis, both insertional and noninsertional, as well as paratenonitis, are more appropriate names (9). In addition, Haglund deformity, retrocalcaneal bursitis, and tendon rupture of varying degrees may be seen. Quite frequently, these disorders occur in combination, producing a variety of symptoms through the Achilles and retrocalcaneal area. A classification system for noninsertional Achilles tendon disorders has been described (10).

PARATENONITIS

Paratenonitis is most commonly seen in the athletic population possibly as a result of overuse, although several job activities may also result in this condition. It is found in runners who have recently increased their training mileage or who may have changed their shoewear running surface. Both overpronation and the cavus foot have been proposed as possible contributing factors resulting in altered rotational forces on the Achilles tendon and subsequent paratenonitis.

On examination, swelling and tenderness along the course of the inflamed paratenon will be appreciated. The symptomatic area will remain constant in location with active dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the ankle, as the paratenon does not move appreciably with the tendon. Squeezing the tendon will elicit pain and possibly crepitus with motion. In paratenonitis without Achilles tendinosis, there will be no underlying thickening of the tendon. Although usually a diagnosis of paratenonitis is made from clinical exam, MRI or ultrasound may be performed, which will reveal thickening of the paratenon. Capillary and fibroblastic proliferation is seen on histologic review, and fluid accumulation as well as adhesions to the tendon may be seen (11).

Nonoperative treatment for Achilles paratenonitis includes training modification for the athlete as well as heel lifts, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, physical therapy modalities (cold therapy, ultrasound, stretching, etc.), and immobilization. Injections of corticosteroid into the tendon are not utilized secondary to an increased chance of rupture. Biomechanical abnormalities may be addressed with orthotic control. Brisement, or injection of sterile saline to release paratenon adhesions, has been described, and extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ECSWT) has also been utilized in the nonoperative treatment of paratenonitis (12,13).

For patients who have failed nonoperative care, excision of the thickened or inflamed paratenon along with release of any associated adhesions is recommended (14). In one study including many high-caliber athletes, 97% good or excellent results using this method were reported. However, almost 50% of the patients in this study also had palpable nodules or diffuse tendinosis (11). Because of concern about damage to the vascularity of the tendon and remaining paratenon secondary to surgical dissection, somewhat more limited approaches have also been described (10,15).

The patient is usually placed in a prone position when performing débridement of the paratenon, although a supine position with the affected leg placed in a Figure 78.4 position can also be used. The incision is placed directly over the area of maximal symptoms along the medial border of the Achilles tendon. Local, general, or balanced anesthesia may be utilized with or without tourniquet control. Areas of paratenon thickening, scarring, and hyperemia are identified and are resected along with any associated adhesions. The tendon is then palpated and visually inspected for any nodularity, etc., that was not appreciated preoperatively on clinical exam or imaging, and débrided if present. Postoperatively, rehabilitation may be instituted after a short period of immobilization in a walking boot. As an alternative to excision of the diseased paratenon, multiple longitudinal incisions in the “peritendinous tissue” have also been described to promote vascular ingrowth (10). A percutaneous technique has also been described with good results (15).

PEARLS

If possible, do not strip the paratenon circumferentially from the tendon, especially anteriorly, to preserve as much vascularity to the tendon as possible.

Carefully develop a full-thickness flap between the paratenon and subcutaneous tissue to aid in healing of the incision.

NONINSERTIONAL ACHILLES TENDINOSIS

In contrast to isolated paratenonitis, patients with noninsertional Achilles tendinosis (NIAT) will present with palpable thickening of the Achilles tendon. Also with NIAT, the nonathletic population is much more frequently affected. Tendon thickening may be symptomatic or asymptomatic and with or without a history of preceding trauma. In addition to interstitial and partial rupture, the etiologies of NIAT also include the etiologies previously described for paratenonitis, as well as the aging process and various forms of repetitive microtrauma.

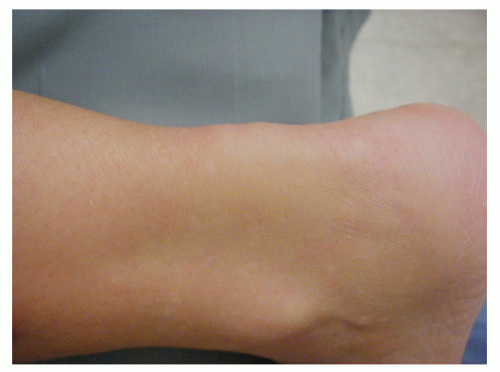

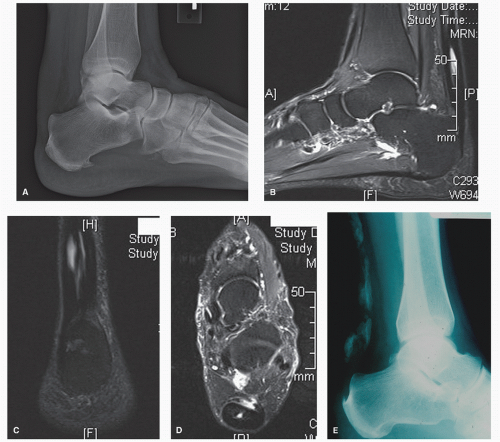

Examination of the patient with NIAT will reveal nodular or fusiform thickening of the tendon itself, usually in the area 3 to 7 cm. proximal to the Achilles tendon insertion (Fig. 78.2). This site corresponds to the area of decreased tendon vascularity. “Relative” thickening may be more pronounced with associated paratenonitis. In symptomatic patients, palpation and squeezing of the thickened area will produce pain. Decreased plantarflexion strength may be present. If interstitial or partial rupture has occurred, there may be increased passive dorsiflexion present. However, in symptomatic individuals, this may not be true secondary to guarding. Radiography, MRI, or ultrasound can be used with NIAT, especially in determining the type and extent of tendon degeneration to aid in surgical planning. Intratendinous calcification may be present (Fig. 78.3).

Upon inspection, areas of NIAT will often exhibit mild discoloration of the thickened site with decreased luster (Fig. 78.4). Mucoid, myxomatous, and fibrinoid degeneration have all been reported pathologically, as well as fibrosis and ossification (16,17 and 18). An increased number of fibroblasts may

be seen, possibly indicating an attempt at repair of any associated interstitial tear.

be seen, possibly indicating an attempt at repair of any associated interstitial tear.

Nonoperative treatment of symptomatic NIAT includes athletic training, job modification, physical therapy modalities, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, heel lifts, ECSWT, and immobilization. A longer period of immobilization may be required with NIAT than with isolated paratenonitis. Once again, corticosteroid injection into the tendon is contraindicated. For the asymptomatic patient with NIAT, simple observation may be all that is necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree