Acetabular Fracture

Brett Bolhofner

Key Points

• Diagnosis or detection of the presence of a fracture involving the acetabulum

• Accurate imaging and defining of the fracture pattern and displacements

• Planning of a surgical approach that will address particular fracture patterns and displacements

• Stable fixation of these fragments by internal fixation

• Postoperative mobilization, prophylactic measures, and follow-up care

Introduction

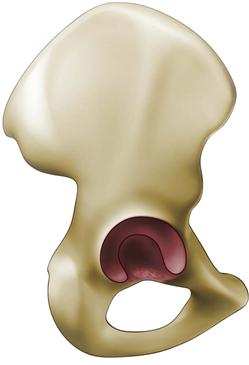

The acetabulum is a socket-like structure contained within the innominate bone (Fig. 47-1). It consists of two basic components: the anterior and posterior columns.1 It is a complex three-dimensional structure, which, in contrast to long bones, is more difficult to visualize and understand from standard planar radiographs. Fractures of the acetabulum provide unique challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Although many surgeons may be comfortable with even difficult fractures on the femoral side of the hip, the same cannot be said for the pelvic side. Reasons for this include the difficulty of (1) understanding the complex three-dimensional geometry of the innominate bone of which the acetabulum is a part, (2) safely accessing the fracture fragments, which may lie deep within the pelvic anatomy, and then (3) accurately reducing and fixing the fractures themselves. Surgical treatment of these injuries depends on knowledge and skill regarding the intrapelvic structures, which often are not part of the acumen of the orthopedic surgeon. Although complications and surgical misadventures in long bone surgery may contribute to morbidity confined to the musculoskeletal system and the particular extremity involved, complications in this type of surgery may also involve multiple unfamiliar organ systems to which the orthopedist often is not exposed.

Figure 47-1 Innominate bone with acetabulum.

In contrast to other “articular” reductions, surgical treatment of acetabular fracture is frequently an indirect reduction of the joint, because the actual articular surface is rarely directly visualized. Essentially, bony landmarks are reduced and reconstructed, and the articular reduction is assessed radiographically.

Entire volumes and fellowships have been dedicated to this complex subject, so the purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview and/or review for the unfamiliar reader who may encounter these injuries.

The basic problems are as follows:

Incidence and Etiology

The incidence of acetabular fracture is believed to be approximately 3 in 100,000 patients; primary causes include motor vehicle accidents and falls from a height.2 Although many are high-energy injuries, low-energy fractures may occur in situations of bony insufficiency. The primary mechanism is a blow to the femur at the level of the knee or trochanter. Because of the infinite positions of the femur related to the pelvis at the time of injury, as well as the infinite directions and amounts of force, fracture pattern variability is high. Acetabular fractures frequently may be associated with other life-threatening injuries.

Classification

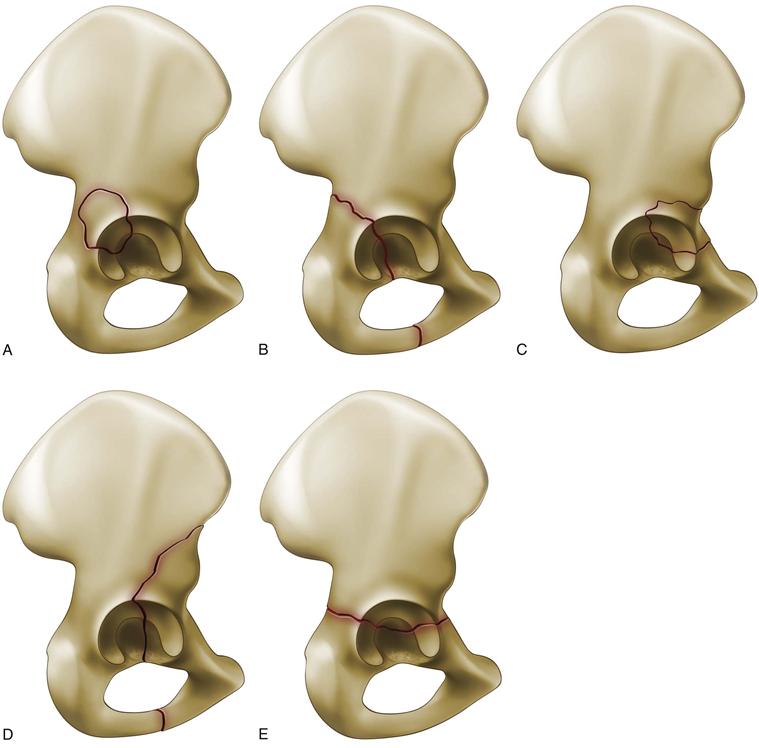

The classification of Leournal and Judet,1 which has been shown to have high interobserver and intraobserver reliability, remains the standard.3 Classification consists of the following five elementary patterns (Fig. 47-2):

Figure 47-2 Elementary fracture patterns according to Letournel and Judet. A, Posterior wall. B, Posterior column. C, Anterior wall. D, Anterior column. E, Transverse.

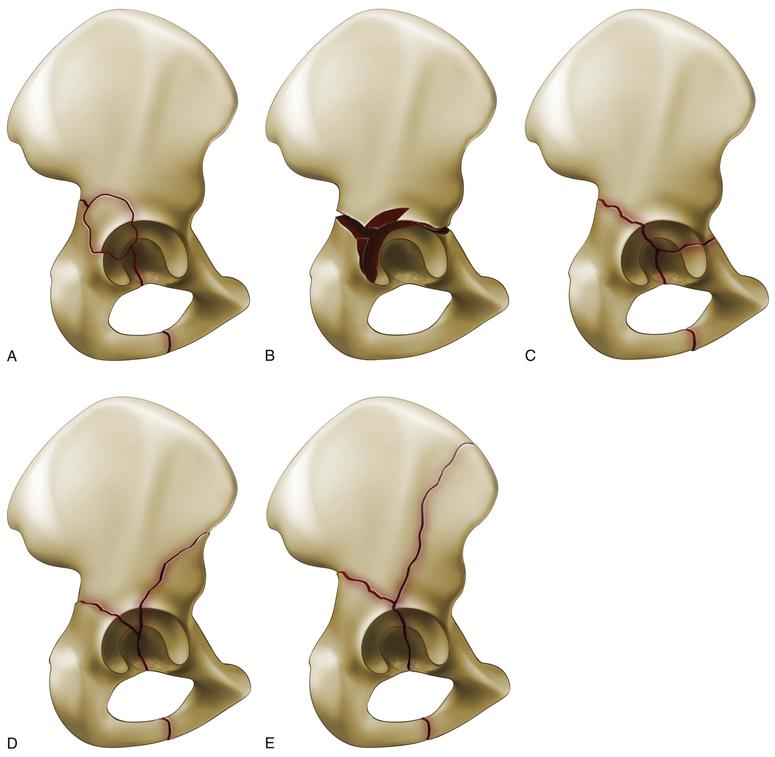

Five associated fracture patterns include the following (Fig. 47-3):

1. Anterior column plus posterior hemitransverse

2. Posterior column plus posterior wall

3. Transverse plus posterior wall

Figure 47-3 Associated fracture patterns according to Letournel and Judet. A, Posterior column posterior wall. B, Transverse posterior wall. C, T-shaped fractures. D, Anterior column posterior hemitransverse. E, Both columns.

Infinite variations in fracture geometry may exist in nature. The purpose of this classification was not just merely to categorize fracture patterns but to define which surgical approach would best fit the particular fracture pattern, because no single approach is ideal for all of these injuries.

Indications

Main considerations for deciding on nonoperative versus operative treatment include the following:

The goal of surgical intervention is to restore the articular surface to anatomicity when and if possible, so that hip joint function may be preserved and ensuing arthrosis may be prevented. Incongruity is poorly tolerated in this load-bearing joint4,5 and likely will lead to poor outcomes.

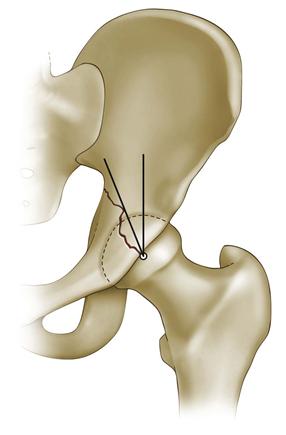

Nonoperative Treatment

Less than 3 mm of articular incongruity is probably the threshold that would be accepted for nonoperative treatment, but of course, other factors such as patient age, comorbidities, and the location of the displacement matter as well.1 An intact roof arc or weight-bearing dome has been shown to be the most critical area to assess and relates most closely to the prognosis for the secondary development of arthrosis4,6-8 (Fig. 47-4). Roof arc measurements may not be helpful, however, in both column fractures, where relative congruence of the acetabular fragments to the head may exist, even though the hip is not in its proper location in space relative to the axial skeleton. Furthermore, roof arc measurements are not useful for all fracture patterns: for example, they would not be helpful at all for determining the need for surgical intervention for posterior wall fractures. Close clinical and radiographic follow-up is necessary in nonoperative treatment to evaluate the patient for any secondary displacement during early healing. Stress views may be helpful in predicting secondary displacement for fractures where the stability of the hip is uncertain from radiographs alone.9

Figure 47-4 Anteroposterior (AP) roof arc measurement.

Operative Treatment

Patient-related factors including age, medical comorbidities, survivability, activity, and functional level, and whether or not the fracture can actually be reconstructed, must be considered in the decision for surgical intervention or nonoperative treatment.

Summary of Surgical Indications

1. Loss of congruency between the femoral head and the acetabulum

2. Greater than 2 mm displacement of the weight-bearing dome

3. Instability or 25% or more of wall involvement in posterior wall fractures

4. Significant intra-articular loose fragments (not small foveal fragments)

When surgical intervention is contemplated, the timing is important, because better results have been reported when surgery is undertaken within 3 weeks of injury. In general, adequate time for assessment of the fracture pattern and the patient as a whole should be taken; however, there are a few indications for immediate intervention; these include irreducible fracture dislocation of the hip, open fracture, and fractures with progressive neurologic or vascular compromise. Local tissue conditions, including the presence of a Morelle-Lavalle injury, abrasions, etc., must be considered.

Preoperative Planning and Assessment

Assessment of the patient as a whole is paramount because associated injuries, some of which may be life threatening, may be present.

Specific evaluation of the fracture itself includes initial plain radiographs followed by Judet views,1 which are 45 degree oblique radiographs. This involves turning the patient 45 degrees, which may require sedation in the acute setting. Judet views, as initially described, are necessary to define fracture patterns in a bone of complex shape within the limitation of single-plane imaging. Computed tomography (CT) scanning is necessary to evaluate specific intra-articular fractures, including especially marginal impaction. Three-dimensional CT scanning has not yet replaced Judet views but may provide the surgeon with a clearer picture of the fracture lines and their displacements and does not require turning the acutely injured patient.

Once the decision for surgery has been made, the following basic requirements must be present:

2. Good operating room team with adequate assistance

3. A surgical table that facilitates reduction and imaging (Fig. 47-5)

Figure 47-5 Patient supine on a radiolucent table equipped with a lateral traction apparatus. One of various options for an anterior or intrapelvic approach.

4. Adequate intraoperative imaging

5. A large volume of specialized reduction clamps and instruments (Fig. 47-6)

Figure 47-6 Various specialized clamps, reduction tools, and retractors.

Surgical Technique and Approaches

Surgical approaches are selected according to the fracture pattern. They may be divided into two basic categories:

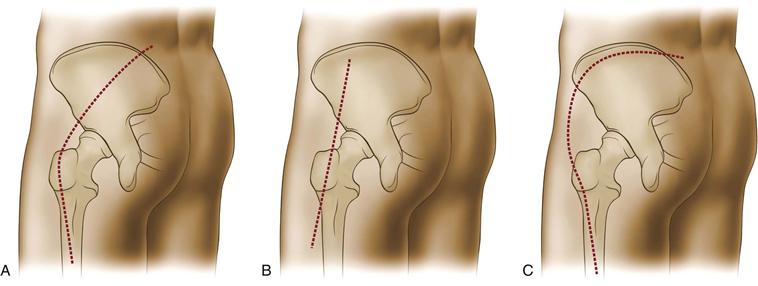

1. Extrapelvic or posterior approaches: These include the Kocher-Langenbeck, extended iliofemoral, and Gibson straight lateral approaches with or without trochanteric osteotomy or surgical dislocation10 (Fig. 47-7).

Figure 47-7 Extrapelvic or posterior incisions. A, Kocher-Langenbeck. B, Gibson. C, Extended iliofemoral.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree