Chapter 2

A framework for physiotherapy management

The overall purpose of physiotherapy for patients with spinal cord injury is to improve health-related quality of life. This is achieved by improving patients’ ability to participate in activities of daily life. The barriers to participation which are amenable to physiotherapy interventions are impairments that are directly or indirectly related to motor and sensory loss. Impairments prevent individuals from performing activities such as walking, pushing a wheelchair and rolling in bed. During the acute phase, immediately after injury when patients are restricted to bed, the key impairments physiotherapists can prevent or treat are pain, poor respiratory function, loss of joint mobility and weakness (see Chapters 8–11). Once patients commence rehabilitation physiotherapists can also address impairments related to poor skill and fitness (see Chapters 7 and 12).

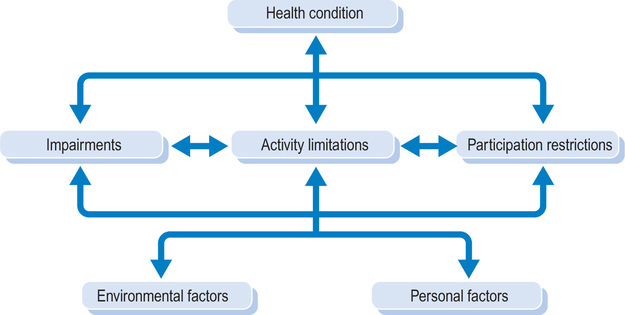

It is possible to define the role and purpose of physiotherapy for patients with spinal cord injury within the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). The ICF was introduced by the World Health Organization in 20011 and is a revised version of the International Classification of Impairment, Disability and Handicap.2 The ICF defines components of health from the perspective of the body, the individual and society (see Figure 2.1). One of its primary purposes is to provide unified and standard language for those working in the area of disability.1, 3

| Step one: | assessing impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions |

| Step two: | setting goals with respect to activity limitations and participation restrictions |

| Step three: | identifying key impairments |

| Step four: | identifying and administering treatments |

| Step five: | measuring outcomes |

Step one: assessing impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions

Assessing activity limitations and participation restrictions

There are several well-accepted assessment tools used to measure activity limitations and participation restrictions,4, 5 including the Functional Independence Measure (FIM®), 6−8 Spinal Cord Independence Measure, 9−11 and Quadriplegic Index of Function12−14 (see Table 2.1). They all measure independence across a range of domains, reflecting different aspects of activity limitations and participation restrictions. For example, they assess ability to dress, maintain continence, mobilize, transfer and feed. Some have been specifically designed for patients with spinal cord injury, and others are intended for use across all disabilities.

Table 2.1

Assessment tools for measuring activity limitations and participation restrictions

| Brief description | |

| General | |

| Functional Independence Measure (FIM®)65, 66 | The FIM assesses activity limitations. It contains 18 items across six domains: self-care, sphincter control, transfers, locomotion, communication and social cognition. Each item is scored on a seven-point ordinal scale ranging from total assistance (one) to complete independence (seven). |

| Spinal Cord Independence Measures (SCIM)9, 10 | The SCIM was developed specifically for patients with spinal cord injury and contains 16 items covering self-care (four items), respiration and sphincter management (four items), and mobility (eight items). The original SCIM was modified in 200167 and more recently a questionnaire version has been devised. |

| Barthel Index68−72 | The Barthel Index contains 15 self-care, bladder and bowel, and mobility items. Transfers and mobility items (both wheelchair and ambulation) encompass 30%, and toileting and bathing a further 10% of the total score. |

| Craig Handicap and Reporting Technique (CHART)73−78 | The CHART was specifically designed for patients with spinal cord injury to measure community integration. It consists of 27 items which cover five domains: physical independence (three questions), mobility (nine questions), occupation (seven questions), social integration (six questions) and economic self-sufficiency (two questions). Each item is assessed on a behavioural criteria (i.e. hours out of bed). It is administered via interview or questionnaire. |

| Clinical Outcomes Variable Scale (COVS)79, 80 | The COVS consists of 13 items scored on a seven-point scale and measures mobility in activities such as rolling, lying to sitting, sitting balance, transfers, ambulation, wheelchair mobility and arm function. Lower scores reflect poorer levels of mobility. Although originally developed for a general rehabilitation population, COVS discriminates across lesion level, injury completeness and walking status in patients with spinal cord injury. |

| PULSES69, 81 | The PULSES assesses activity limitation and participation restriction of those with chronic illness and covers six domains: physical condition (P), upper limb function (U), lower limb function (L), sensation (S), excretory function (E) and support factors (S). The scoring for each item ranges from one (independent) to four (fully dependent). |

| Quadriplegic Index of Function (QIF)14 | The QIF was specifically designed for patients with tetraplegia. It contains 10 items, three of which encompass mobility (transfers 8%, wheelchair mobility 14% and bed activities 10%). Each item is scored on a five-point scale. There is a shorter form of the original QIF. |

| The Katz Index of ADL82 | The Katz Index of ADL assesses independence in six activities including bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence and feeding. Each activity is scored on a two-point scale, and summated into an overall score (represented by letters from A to G). There are no mobility items. |

| SF-36® Health Survey83, 84 | The SF-36 measures health-related quality of life in eight domains (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, mental health). These can be summarized into two measures (physical and mental). The SF-36 has been used in patients with spinal cord injury.85−88 |

| Sickness Impact Profile (SIP-136)89 | The SIP-136 is a generic measure of the impact of disability on physical status and emotional well-being. It is administered via a 136-item questionnaire which requires ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses. It has 12 domains including mobility and ambulation items. A shorter version (68 items) is also available.90 It has three main domains including a physical domain which assesses ambulation, mobility and body care. |

| Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)91−94 | The COPM was designed to assess patients’ perspectives about changes in activity limitations and participation restrictions. The COPM is administered in a semi-structured interview where patients are required to identify specific activity limitations and participation restrictions. Patients use a 10-point scale to rate each identified problem with respect to importance, performance and satisfaction. The COPM is primarily used to monitor change. |

| The Physical Activity Recall Assessment for People with Spinal Cord Injury (PARA-SCI)95, 96 | The PARA-SCI is a self-report measure of physical activity. It was designed for patients with spinal cord injury and is administered via a semi-structured interview. The time spent on all physical activities related to leisure and daily living is recorded. Each activity is graded for intensity. |

| Valutazione Funzionale Mielolesi (VFM)97, 98 | The VFM questionnaire was developed specifically for patients with spinal cord injury to assess activity limitations. It covers bed mobility, eating, transfers, wheelchair use, grooming and bathing, dressing and social and vocational skills. |

| The Tufts Assessment of Motor Performance (TAMP)99−101 | The TAMP was developed to measure gross and fine motor performance of the upper and lower limbs. It consists of 105 tasks grouped into 31 domains including fine hand function and independence with dressing, mobility, transfers and wheelchair skills. Each item is rated on a seven-point scale. |

| Needs Assessment Checklist (NAC)28 | The NAC was designed specifically for patients with spinal cord injury to measure the success of rehabilitation. It consists of 199 items grouped into nine domains including activities of daily living, skin management, bladder management, bowel management, mobility, wheelchair and equipment, community preparation, discharge coordination and psychological issues. It does not differentiate between the ability to direct others to help and the ability to independently perform activities. |

| Gait-related | |

| Walking Index for Spinal Cord (WISCI)102−104 | The WISCI was developed specifically for patients with spinal cord injury. Injury It measures ability to walk 10 m and need for physical assistance, orthoses and walking aids on an incremental scale ranging from zero (unable to stand or walk) to 20 (ambulates without orthoses, aids or physical assistance). |

| The Spinal Cord Injury Functional Ambulation Inventory (SCI-FAI)105 | The SCI-FAI is an observational gait assessment which uses an ordinal scale to rate nine different aspects of walking. It includes a 2-minute walk test. |

| The Walking Mobility Scale106−108 | The Walking Mobility Scale is a five-point scale that classifies ability to walk into the following categories: physiological ambulators, limited household ambulators, independent household ambulators, limited community ambulators and independent community ambulators. |

| Timed Up and Go109, 110 | The Timed Up and Go test measures the time taken to stand up from a chair, walk 3 m, turn around and walk back to sit down on the chair. No physical assistance is given. |

| 10 m Walk Test65, 111, 112 | The 10 m Walk Test measures speed of walking (m.sec−1). Patients are instructed to walk 14 m at their preferred speed but time is only recorded for the middle 10 m. |

| 6-minute Walk Test65, 113 | The 6-minute Walk Test is a measure of endurance. Patients are instructed to walk as far as possible in 6 minutes, taking rests whenever required. The distance covered and the number of rests required are recorded. |

| Functional Standing Test (FST)114 | The FST measures patients’ ability to reach while standing. It consists of 20 items requiring manipulation and lifting of different objects. Orthoses can be worn and the tasks are done as quickly as possible. Some of the tasks are from the Jebsen Test of Hand Function.115 |

| Modified Benzel Classification116 | The Modified Benzel Classification is a seven-point scale that classifies patients according to both neurological and ambulatory status. Neurological classification is based on ASIA and ambulatory classification is crudely based on key gait parameters including ability to walk 25–250 feet (, 7–75 m). |

| Upper limb function | |

| Capabilities of Upper Extremity Instrument (CUE)117 | The CUE is a measure of upper limb function. It was specifically designed for patients with tetraplegia and is administered via a self-report questionnaire. Patients rate their ability to perform 32 different tasks on a seven-point scale. |

| The Tetraplegic Hand Activity Questionnaire (THAQ)118 | The THAQ was designed to measure patients’ perceptions about their hand and upper limb function. Patients are required to rate 153 motor tasks according to their ability to perform the task (four-point scale), need for an aid (four-point scale) and importance of the task (three point scale). |

| The Common Object Test (COT)119 | The COT was designed to evaluate the usefulness of neuroprostheses. Patients are required to perform 14 motor tasks. Each task is divided into its sub-tasks and scored on a six-point scale according to the amount of assistance required. |

| Grasp and Release Test (GRT)120 | The GRT is a test of hand function. It was initially designed to evaluate the usefulness of neuroprostheses in patients with C5 and C6 tetraplegia. The test requires patients to use either a palmar or lateral grasp to manipulate six different objects. Patients are assessed on the speed at which they can complete the tasks as well as their success rate. |

| Wheelchair mobility | |

| Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology (QUEST)121, 122 | The QUEST is a 12-item questionnaire which assesses patients’ satisfaction with assistive technology, including wheelchairs. Each item is rated on a six-point scale ranging from ‘not at all satisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’. Eight items relate to the device and four items to service provision. |

| Modified Functional Reach (mFRT)123 | The mFRT assesses patients’ ability to reach forward while seated. The Test maximal distance reached following three trials is recorded. |

| Timed Motor Test (TMT)124 | The TMT was designed for children with spinal cord injury. It consists of six items and children are assessed on the time taken to complete each task. The tasks include putting on clothing, transferring and manoeuvring a manual wheelchair. |

| Five Additional Mobility and Locomotor Items (5-AML)125, 126 | The 5-AML was specifically designed for patients who are wheelchair-dependent. It contains five items assessing patients’ ability to transfer, move about a bed and mobilize in a manual wheelchair. It is used in conjunction with the FIM. |

| Wheelchair Circuit Test (WCT)127 | The WCT contains nine items and assesses different aspects of wheelchair mobility and the ability to transfer and walk. Three items require propelling a wheelchair on a treadmill. |

| Wheelchair Skills Test (WST)15, 128, 129 | The WST is a 57-item test to assess ability to mobilize in a manual wheelchair. It includes simple tasks such as applying brakes, and complex tasks such transferring and ascending kerbs. Each item is scored on a three-point scale reflecting competency and safety. A questionnaire version is also available.130 |

More physiotherapy-specific assessments of activity limitations and participation restrictions quantify different aspects of mobility and motor function. For example, some assess the ability to walk (e.g. the WISCI, 10 m Walk Test, the Motor Assessment Scale, 6-minute Walk Test, Timed Up and Go), ability to use the hands (e.g. the Grasp and Release test, Sollerman test, Carroll test, Jebsen test) and ability to mobilize in a wheelchair15, 16 (see Table 2.1). There is as yet no consensus on the most appropriate tests, and currently physiotherapists tend to use a battery of different assessments, including non-standardized, subjective assessments of the way patients move.

Assessing impairments

The physical assessment also includes an assessment of impairments. These are similar to standard assessments used by physiotherapists in other populations. They include assessments of strength, sensation, respiratory function, cardiovascular fitness and pain. Details of how to assess impairments in patients with spinal cord injury can be found in subsequent chapters (see Chapters 8–11).

Step two: setting goals

Benefits of goals

Goal setting is an important aspect of a comprehensive physiotherapy and rehabilitation programme.17−28 The process needs to be patient-centred. Initially, a few key goals of rehabilitation are articulated by the patient and negotiated with the multi-disciplinary team.17, 19, 22, 23, 25, 29−33 These goals should be expressed in terms of participation restrictions.20, 25 For example, a key goal of rehabilitation might be to return to work or school. Physiotherapy-specific goals then need to be identified and linked to each participation restriction goal. The physiotherapy-specific goals should be functional and purposeful activities as defined within the activity limitation and participation restriction domains of ICF and, specifically, within the ICF sub-domains of mobility, self-care and domestic life. These sub-domains include tasks such as pushing a manual wheelchair, rolling in bed, moving from lying to sitting, eating, drinking, looking after one’s health, and pursuing recreation and leisure interests (see Ref. 34 for examples of ways to articulate functional goals appropriate for patients with spinal cord injury). Physiotherapy-specific goals are formulated in conjunction with the patient and other team members who share responsibility for their attainment. Both short- and long-term goals need to be set.24, 25 These may include goals to be achieved within a week or goals to be achieved over 6 months. In addition, specific goals (or targets) should be set as part of each treatment session25 (see Chapter 7).

Goals are important for several reasons.24 They ensure that the expectations of patients and staff are similar and realistic, and provide clear indications of what everyone is expected to achieve.26 If compiled in an appropriate way, they actively engage patients in their own rehabilitation plan, empowering them and ensuring that their wishes and expectations are met.26 Without goals, rehabilitation programmes can lack direction, and patients can feel like the passive recipients of mystical interventions.19, 22, 23, 30, 35 Goals also help focus the rehabilitation team on the individual needs of patients, and provide team members with common objectives.24 Perhaps most importantly, goals provide a source of motivation and enhance adherence.

Goals are also used to monitor the success of therapy and to identify problems. Goals achieved indicate success and goals not achieved indicate failure. Failure may be due to any number of reasons which need exploring. For example, a patient may fail to achieve a goal because of medical complications or because equipment fails to arrive, factors which may be difficult to avoid. Failure to achieve goals may reflect poor therapy attendance. Alternatively, failure may indicate unrealistic goals which need revising. A risk of excessive reliance on goals to measure success is that it encourages the selection of non-challenging goals which have a high likelihood of success.27

Guidelines to setting goals

Goals should be SMART. That is, they should be: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Timebound.36 Physiotherapy-related goals need to be based on predictions of future independence, taking into account contextual factors such as patients’ and families’ perspectives, priorities and personal ambitions.19, 35, 37 Other factors which influence outcome include access to products, technology and support, and personal attributes such as age, personality and anthropometrical characteristics.37−43 Clearly, however, the strongest predictor of future independence is neurological status.32, 44, 45 Neurological status determines the strength of muscles which in turn largely determines patients’ ability to move.

A simplistic summary of levels of innervation for key upper and lower limb muscles is provided in Table 2.2 (for more details see Tables A1 and A2 in the Appendix). The summary is simplistic because muscles have been grouped together even though different muscles and parts of the same muscle often receive innervation from different spinal nerve roots. For example, the pectoralis muscles consist of pectoralis minor and the sternocostal and clavicular parts of pectoralis major. These muscles receive innervation from C5 to T1.46

Table 2.2

The levels at which muscles receive sufficient innervation to enable reasonable movement46

| C4 | Diaphragm | |

| C5 | Shoulder | Flexors |

| Abductors | ||

| Elbow | Flexors* | |

| C6 | Shoulder | Extensors |

| Adductors | ||

| Wrist | Extensors* | |

| C7 | Elbow | Extensors* |

| Wrist | Flexors | |

| Finger | Extensors | |

| Thumb | Abductors and adductors | |

| C8 | Finger | Flexors* |

| Thumb | Flexors and extensors | |

| T1 | Finger | Abductors* |

| Adductors | ||

| T1–T12 | Intercostals, abdominals and trunk | |

| L2 | Hip | Flexors* |

| Adductors | ||

| L3 | Knee | Extensors* |

| L4 | Hip | Abductors |

| Ankle | Dorsiflexors* | |

| L5 | Hip | Extensors |

| Toe | Extensors* | |

| S1 | Knee | Flexors |

| Ankle | Plantarflexors* | |

| S2 | Toe | Flexors |

*The ASIA muscles are asterisked (see Appendix for more details).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree