Chapter 98 5-Hydroxytryptophan

Introduction

Introduction

5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) (Figure 98-1) is the intermediate between tryptophan and serotonin.1 Although the use of 5-HTP may be relatively new to most clinicians, it has been available through pharmacies for several years and has been intensely researched for the past three decades. It has been used clinically since the 1970s.

Tryptophan and 5-Hydroxytryptophan Metabolism

Tryptophan and 5-Hydroxytryptophan Metabolism

Once tryptophan is absorbed from the intestines, it is carried by the blood to the liver, along with other amino acids consumed during the meal. Ingested tryptophan can pass into the general circulation, metabolize into blood proteins, or convert to kynurenine (which then goes on to form nicotinic acid, picolinate, and other important metabolites) in the liver. After conversion to kynurenine, it cannot be converted to serotonin. The same is likely true if the tryptophan is incorporated into blood proteins. Unchanged tryptophan can be converted to 5-HTP and then to serotonin. However, if this conversion occurs outside the brain, brain chemistry will not be influenced. Even under the best-case scenario, only 3% of a dosage of L-tryptophan in supplemental or dietary form is likely to be converted to serotonin in the brain.2

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

Several pharmacokinetic studies showed that about 70% of a dose of 5-HTP taken orally is delivered to the bloodstream.3,4 The remaining 30% is metabolized by intestinal cells.

Ample evidence from these pharmacokinetic studies, as well as clinical studies, indicates that once absorbed, 5-HTP is delivered to the brain, resulting in increased formation of not only serotonin but also other brain chemicals (e.g., the monoamines melatonin, endorphins, dopamine, and norepinephrine). By raising brain serotonin levels, as well as by other effects, 5-HTP showed positive effects in the various conditions associated with low serotonin levels.

By raising serotonin, melatonin, and β-endorphin levels, 5-HTP has a significant impact on helping to regulate and improve brain chemistry. 5-HTP was also shown to raise the levels of other important neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and norepinephrine.5 The ability of 5-HTP to increase both serotonin (and other indolamines) and catecholamines is quite significant and unique to 5-HTP. It is an effect that 5-HTP does not share with L-tryptophan. The effective treatment of depression requires more than simply raising serotonin levels; catecholamine levels must also be increased. 5-HTP provides the brain with both sets of tools.

5-Hydroxytryptophan Versus L-Tryptophan

In a head-to-head comparison study of 5-HTP and L-tryptophan in the treatment of depression, 5-HTP proved superior.6 The proposed reason is the fact that 5-HTP easily crosses the blood–brain barrier and is not affected by competing amino acids. 5-HTP affects brain chemistry in a broader and more positive fashion. L-Tryptophan is often effective in cases of low serotonin, especially insomnia, but 5-HTP is more broadly effective.

Perhaps the biggest advantage of 5-HTP over L-tryptophan is that it is safer.7 Although L-tryptophan is safe if properly prepared and free of the contaminants linked to eosinophilia myalgia syndrome (EMS), 5-HTP is inherently safer. The reasons are that taking L-tryptophan to produce positive effects in the treatment of depression, insomnia, and other low serotonin conditions requires a relatively high dose (e.g., a minimum of 2000 mg in insomnia and 6000 mg in depression). At high doses such as these, L-tryptophan is potentially problematic, because more L-tryptophan will be shunted toward the kynurenine pathway, and L-tryptophan promotes oxidative damage. Excessive levels of dietary tryptophan or high doses of L-tryptophan result in tryptophan actually acting as a free radical.8 In contrast, 5-HTP is an antioxidant.9 This antioxidant difference is due to the additional molecule of oxygen and hydrogen in 5-HTP. This simple change in molecular structure allows the phenolic ring structure to effectively accept or quench the unpaired electron of a free radical.

Clinical Applications

Clinical Applications

A massive amount of evidence suggests that low serotonin levels are a common consequence of modern living. The lifestyle and dietary practices of many people living in this stress-filled era result in lowered levels of serotonin within the brain. As a result, many people are overweight, crave sugar and other carbohydrates, experience bouts of depression, get frequent headaches, and have vague muscle aches and pains. All of these maladies are correctable by raising brain serotonin levels. The primary therapeutic applications for 5-HTP are low serotonin states, as listed in Box 98-1.

Depression

Some of the first clinical studies on 5-HTP for the treatment of depression began in the early 1970s in Japan. The first study involved 107 patients with either unipolar depression or manic bipolar depression.10 These patients received 5-HTP at dosages ranging from 50 to 300 mg/day. The researchers observed a quick response (within 2 weeks) in more than half of the patients. Seventy-four of the patients either experienced complete relief or significantly improved, and none experienced significant side effects. These promising results were repeated in several other Japanese studies. An interesting aspect in two of these studies was the fact that 5-HTP was shown to be effective in some patients (50% in one study, 35% in another) who had not responded positively to any other antidepressant agent.11,12

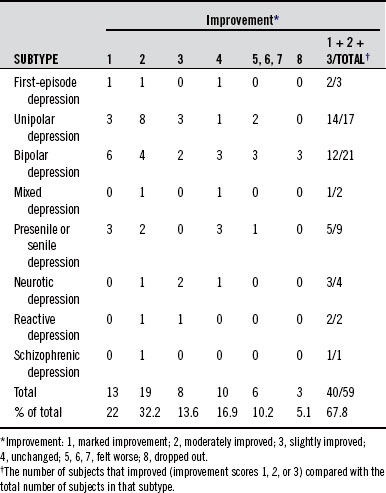

The most detailed of the Japanese studies was conducted in 1978.13 The study enrolled 59 patients with depression (30 males and 29 females). The groups were mixed, in that both unipolar and bipolar depressions were included, along with a number of other subcategories of depression. The severity of the depression in most cases was moderate to severe. Patients received 5-HTP in dosages of 50 or 100 mg three times a day for at least 3 weeks.

The antidepressant activity and clinical effectiveness of 5-HTP was determined using a rating scale developed by the Clinical Psychopharmacology Research Group in Japan. The improvements among the various patients are detailed in Table 98-1. These results indicated that 5-HTP was helpful in 14 of 17 patients with unipolar depression and 12 of 21 patients with bipolar depression. The degree of improvement in most cases ranged from excellent to very good.

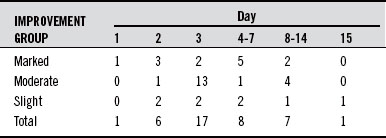

The results achieved in this open study were quite good, given how rapidly they were achieved. Thirty-two of the 40 patients who responded to 5-HTP did so within the first 2 weeks of therapy. Typically, in most studies with antidepressant drugs, the benefits are not apparent until after 2 weeks to 1 month of use. For this reason, the length of study when assessing antidepressant drugs should be at least 6 weeks, because it may take that long to significantly affect brain chemistry in a positive manner. In contrast, many of the studies with 5-HTP were shorter than 6 weeks because statistically significant results were achieved so soon (Table 98-2). However, the longer 5-HTP is used, the better the results. Some people may need to be on 5-HTP for at least 2 months before they experience benefits.

A 5-HTP dosage of 150 to 300 mg/day is sufficient in most cases. For example, in one study, it was shown that 13 of 18 subjects with depression given 5-HTP at a level of 150 or 300 mg/day experienced good to excellent results.14 This percentage of responders is quite good, but if the level of serotonin in the blood is viewed as a rough indicator of brain serotonin levels, some interesting conclusions can be made (Table 98-3). In some cases, a higher dosage may be necessary.

TABLE 98-3 Level of Serotonin in Blood (nanograms per milliliter): Controls, Responders, and Nonresponders

| BEFORE | AFTER 1 Wk (150 OR 300 mg/day 5-HTP) | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal subjects | 150 | |

| Responders | 78 | 148 |

| Nonresponders | 56 | 77 |

5-HTP, 5-Hydroxytryptophan.

The measurements in Table 98-3 suggest that serotonin levels in depressed individuals are considerably lower than those found in normal subjects, and that individuals who respond to 5-HTP show a rise in serotonin to levels consistent with normal subjects. The level of serotonin in those who do not respond to 5-HTP remains quite low. These results imply that nonresponders may require higher doses to raise serotonin levels or that additional support may be necessary. When prescribing higher doses, it is important that the 5-HTP be taken in divided doses not only to reduce the problem with nausea, but also because the rate of brain cell uptake of 5-HTP is limited.

The first studies of 5-HTP were open trials.15 The antidepressive effects of 5-HTP were also compared with L-tryptophan in the early 1970s.6 In one study, 45 subjects with depression were given L-tryptophan (5 g/day), 5-HTP (200 mg/day), or a placebo. The patients were matched in clinical features (e.g., age, sex) and severity of depression. The main outcome measure was a rating scale called the Hamilton Depression Scale (HDS), the most widely used assessment tool in clinical research on depression.

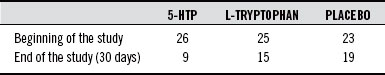

Symptoms assessed by the HDS include depression, feelings of guilt, insomnia, gastrointestinal symptoms and other bodily symptoms of depression (e.g., headaches, muscle aches, heart palpitations), and anxiety. The HDS is popular in research because it provides a good assessment of the overall symptoms of depression. Table 98-4 shows the results of the study.

TABLE 98-4 Hamilton Depression Scale from a Comparative Study of 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), L-Tryptophan, and Placebo

A review of head-to-head comparison studies showed that 5-HTP, at a dosage of 200 mg/day, produced therapeutic success on a par with tricyclic antidepressant drugs.16 Research also showed that combining 5-HTP with clomipramine and other types of antidepressant drugs produced better results than any of the compounds given alone.17–22 For example, in one study, 5-HTP combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor demonstrated significant advantages compared with the monoamine oxidase inhibitor alone (Table 98-5).21

TABLE 98-5 Change in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

| 5-HTP + MAO | MAO + PLACEBO | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial measurement | 28.67 | 26.33 |

| After 8 days | 16.67 | 19.23 |

| After 15 days | 11.77 | 6.03 |

5-HTP, 5-hydroxytryptophan; MAO, monoamine oxidase.

Modified from Alino JJ, Gutierrez JL, Iglesias ML. 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) and a MAOI (nialamide) in the treatment of depressions. A double-blind controlled study. Int Pharmacopsychiatry 1976;11:8-15.

Because 5-HTP was expensive in 1972, researchers developed a test to determine who was most likely to respond to it, so that it would not be wasted on people who were unlikely to respond.15,23 The test involved the patients first having a spinal tap to measure the level of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA, the breakdown product of serotonin) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The drug probenecid, which prevents the transport of 5-HIAA from the CSF to the bloodstream, was administered for the next 3 days. As a result of this blocking action, the amount of serotonin produced over a 4-day period could be calculated by a repeat spinal tap on day 4. Because the 5-HIAA could not leave the CSF, it accumulated and provided a measure of serotonin manufacture.

The researchers discovered that the average level of 5-HIAA after 3 days of probenecid was significantly lower in depressed individuals than in controls matched for age, sex, and weight. This low level of serotonin reflected a decreased rate of manufacture within the brain. 5-HTP was most effective in patients with a low 5-HIAA response to 3 days of probenecid.23–25 In other words, 5-HTP is most effective as an antidepressant when the amount of serotonin manufactured in the brain is reduced.

As stated earlier, 5-HTP often produces good results in patients who are unresponsive to antidepressant drugs. One of the more impressive studies involved 99 patients described as having “therapy-resistant” depression.26 These patients did not respond to any previous therapy, including all available antidepressant drugs and electroconvulsive therapy. These therapy-resistant patients received 5-HTP at dosages averaging 200 mg/day but ranging from 50 to 600 mg/day. Complete recovery was seen in 43 of the 99 patients, and significant improvement was noted in 8 more. Such significant improvement in patients with long-standing, unresponsive depression is quite impressive, prompting the author of another study to state the following27:

A 1987 review article on 5-HTP in depression highlighted the need for well-designed, double-blind, head-to-head studies of 5-HTP versus standard antidepressant drugs.28 Although 5-HTP was viewed as an antidepressant agent with few side effects, the authors of this review felt that the big question to answer was how 5-HTP compared with the new breed of antidepressant drugs, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) like Prozac, Paxil, and Zoloft. In 1991, a double-blind study comparing 5-HTP with an SSRI was conducted in Switzerland.29 5-HTP was compared in the study with the SSRI fluvoxamine (Luvox). Fluvoxamine is used primarily in the United States as a treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder, an anxiety disorder characterized by obsessions and compulsions affecting an estimated 5 million Americans. Fluvoxamine exerts antidepressant activity comparable to (if not better than) other SSRIs like Prozac, Zoloft, and Paxil.

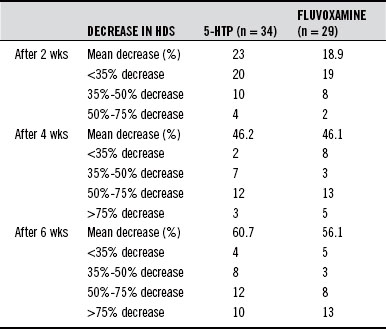

In the study, subjects received either 5-HTP (100 mg) or fluvoxamine (50 mg) three times a day for 6 weeks. The assessment methods used to judge effectiveness included the HDS, self-assessment depression scale (SADS), and physician’s assessment (Clinical Global Impression). As indicated in Table 98-6, the percentage decrease in depression was slightly better in the 5-HTP group (60.7% versus 56.1%). 5-HTP was quicker acting than the fluvoxamine, and a higher percentage of patients responded to 5-HTP than to fluvoxamine.

TABLE 98-6 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) Versus Fluvoxamine in Percentage Changes in the Hamilton Depression Scale (HDS)

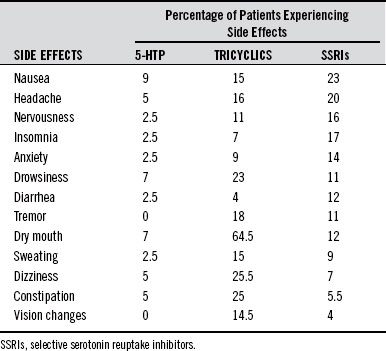

5-HTP is equal to or better than standard antidepressant drugs, and the side effects are much less severe (Table 98-7). In the study comparing 5-HTP with fluvoxamine, this is how the physicians described the differences among the two groups: Whereas the two treatment groups did not differ significantly in the number of patients sustaining adverse events, the interaction between the degree of severity and the type of medication was highly significant: fluvoxamine predominantly produced moderate to severe side effects; oxitriptan (5-HTP) produced primarily mild forms of adverse effects.

L-Tyrosine: An Adjunct to 5-Hydroxytryptophan

In the early 1970s, researchers discovered that, in about 20% of patients who responded well to 5-HTP, the results tended to decrease after 1 month of treatment. The antidepressant effects of 5-HTP in these subjects began to wear off gradually after the first month despite the fact that the level of 5-HTP in the blood, and presumably the level of serotonin in the brain, remained at the same level as when they were experiencing benefits.8

The researchers discovered that although serotonin levels appeared to stay at the same levels after 1 month of treatment, the levels of the other important monoamine neurotransmitters, dopamine and norepinephrine, declined.28 As discussed earlier, when depressed patients are treated with 5-HTP, they experience a rise not only in serotonin but also in catecholamines like dopamine and norepinephrine. In about 20% of subjects, the catecholamine-enhancing effects of 5-HTP tended to wear off. Providing these patients with L-tyrosine, the amino acid precursor to the catecholamines, helped to reestablish the efficacy of 5-HTP.8,30 The dosage was 200 mg/day for 5-HTP and 100 mg/kg body weight for L-tyrosine. This dosage for L-tyrosine is quite high and requires substantial clinical supervision.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree