Within 5 years, chiropractic celebrated its centennial, chiropractic education celebrated 100 years, and a third millennium was ushered in. These times are appropriate to stop and consider the major themes in chiropractic history. The major themes of chiropractic are identified in this chapter and, when possible, are chronologically discussed. Although selection of any list of major events in chiropractic is, of course, a subjective process, this text relies heavily on the works of Walter Wardwell, Russell Gibbons, William Rehm, Herbert Vear, Vern Gielow, Pierre Louis Gaucher-Peslherbe, and Joseph Keating, Jr. in developing the selections and expounding on the themes that are discussed. The author of this text is indebted to these scholars of chiropractic history.

DANIEL DAVID PALMER AND THE FORMULATION OF THE CHIROPRACTIC THEORY

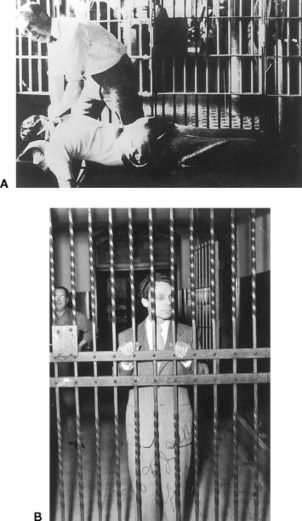

The occasion of the first chiropractic adjustment is, of course, the first major event in chiropractic. Daniel David (D.D.) Palmer, Canadian by birth, performed the first adjustment on an African-American man, Harvey Lillard, on September 18, 1895, in Davenport, Iowa (Fig. 3-1). Palmer, who was 50 years old at the time, tells the story:

|

| Fig. 3-1 Artist John Dyeuss’ rendering of the first adjustment, performed by D.D. Palmer on Harvey Lillard, September 1895. (Courtesy Chiropractic Centennial Foundation, Davenport, Iowa.) |

He had been so deaf for seventeen years that he could not hear the racket of a wagon or the ticking of a watch. I made inquiry as to the cause of his deafness, and was told that when he was exerting himself in a cramped, stooping position, he felt something give way in his back and immediately became deaf. An examination showed a vertebra racked from its normal position. I reasoned that if the vertebra was replaced, the man’s hearing could be restored. I racked it into position by using the spinous process as a lever, and soon the man could hear as before. There was nothing “accidental” about this as it was accomplished with an objective in view, and the result expected was obtained. 1

Palmer had been studying and practicing magnetic healing* since 1886, and his evolution from magnetic healing to chiropractic was gradual. He was well read in the fields of anatomy, physiology, neurology, and pathology2 and used his extensive knowledge to develop a theory to explain his clinical successes. When Palmer applied his newly developed technique to other patients, he observed that other disorders responded to the thrusts he used to reposition vertebrae. One of his patients had a heart condition that had failed to respond to the usual medical care. Palmer examined the patient’s spine and found a displaced fourth dorsal vertebra that he theorized was pressing against the nerves that segmentally innervate the heart. After he adjusted this segment of the spine, the patient experienced relief. Of this second attempt, Palmer said, “Then I began to reason, if two diseases, so dissimilar as deafness and heart trouble, came from impingement, a pressure on the nerves, were not other diseases due to a similar cause?”3

*Magnetic healing was a form of energy healing involving the laying on of hands. It may also have included vigorous rubbing and manipulation of various kinds.

D.D. Palmer accepted his first student in 1897, and soon students were graduating from his Palmer School and Infirmary (later renamed Palmer School of Chiropractic [PSC]) to both practice and teach chiropractic. In 1903, D.D. Palmer and his son Bartlett Joshua (B.J.) formed an equal partnership, which was to continue until 1906. In that year, D.D. Palmer was tried and found guilty in Scott County, Iowa, of practicing medicine without a license, after which he sold his share of the PSC to his son and moved west, where he opened schools in Oklahoma, Oregon, and California.

After leaving Davenport, D.D. Palmer assembled a collection of his writings in his 1000-page magnum opus, The Chiropractor’s Adjuster: A Textbook of the Science, Art, and Philosophy of Chiropractic for Students and Practitioners (1910). Undoubtedly, D.D. Palmer’s formulation of the theory of chiropractic and its elucidation through his writings are the seminal and most important event in the history of chiropractic.

B.J. PALMER AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHIROPRACTIC

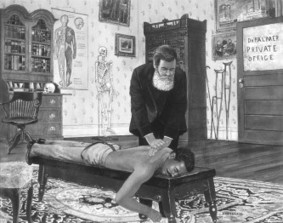

B.J. Palmer was the second major influence on the development of chiropractic (Fig. 3-2). Always careful to describe his father as the “founder” of chiropractic, B.J. Palmer considered himself the “developer” of chiropractic, and proceeded to do so in style. On purchasing his father’s half of PSC, B.J. began developing it into one of the largest health practitioner schools in the country, with the school’s population growing from 400 in 1911 to 3000 by 1923. 4 Both Gibbons5 and Wardwell6 attribute the survival of the fledgling chiropractic profession to B.J. Palmer’s flamboyant marketing and his dogged insistence that chiropractic remain “pure and unadulterated.” According to Wardwell, “Without B.J. chiropractic might not have survived. A colorful multimedia salesman for chiropractic, he used lectures, pamphlets, 27 books, and his own radio station to spread the word about chiropractic to students, patients, and the public.”7 B.J. was a charismatic and energetic speaker who traveled around the country, boosting chiropractic and testifying on behalf of chiropractors before courts and state legislatures. Although B.J. was a controversial figure, his pronouncements against raising educational standards (he declared that they were “veneer and polish…, which [would] weaken the profession and cause a large reduction in the number of chiropractors,”) were used in the courtroom against chiropractic; however, not a man or woman who knew him questioned his undying loyalty to chiropractic.

|

| Fig. 3-2 B.J. Palmer, D.D. Palmer’s son, president of the Palmer School of Chiropractic (PSC) from 1906 until his death in 1961 and a leading force in the development of chiropractic. (Courtesy Library Special Collections, Palmer College of Chiropractic, Davenport, Iowa.) |

DEFENSE OF CHIROPRACTIC IN COURT

A third major event or series of events in the history of chiropractic was the struggle to defend chiropractors in court against the charge of practicing medicine without a license. Although D.D. Palmer was not the first to be accused of practicing medicine or osteopathy without a license (he was tried and found guilty of the offense in 1906), the trial of Shegataro Morikubo (PSC graduate, 1903) in La Crosse, Wisconsin, in 1907 was a watershed event that helped determine the strategy that chiropractors would adopt to defend themselves against future charges of unlicensed medical practice.

The jury acquitted Morikubo. The defense attorney, Tom Morris, convinced the jury that chiropractic was not osteopathy or medicine; rather, it was a new form of treatment. B.J. Palmer retained Tom Morris as counsel for the Universal Chiropractors Association (UCA), and they proceeded to use the argument that chiropractic was a separate and distinct science from medicine. The central purpose of the UCA, with B.J. Palmer serving as its secretary for 20 years, was to raise funds to pay bail and fines for arrested chiropractors who adhered to the “straight” chiropractic philosophy. In addition, its purpose was to defend chiropractors in court and to lobby for state licensure of chiropractors, separate and distinct from medical practice acts. By 1927 the UCA had defended chiropractors in 3300 court cases. 8

OTHER PIONEERS

Although B.J. Palmer casts a giant shadow on the landscape of chiropractic history, several other influential pioneers deserve mention.

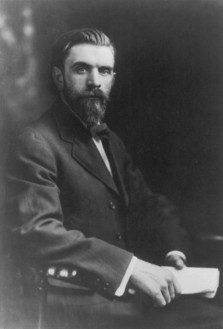

Solon Langworthy, the founder of the first school to provide serious competition to D.D. Palmer’s PSC, was very influential in early chiropractic history (Fig. 3-3). With Oakley Smith and Minora Paxson, Solon Langworthy published the first textbook on chiropractic in 1906, A Textbook of Modernized Chiropractic. He also published an early journal, The Backbone, which D.D. and B.J. used as a model for their journal, The Chiropractor. Langworthy also organized the first chiropractic association in 1905, the American Chiropractic Association (ACA) (not related to the current ACA). Although Langworthy’s school, journal, and association did not last long, his impact was far reaching on the early profession.

|

| Fig. 3-3 Solon Langworthy, president of the American School of Chiropractic in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, co-author of the first chiropractic textbook, editor of the early journal The Backbone, and the first serious competitor to the PSC. (Courtesy Library Special Collections, Palmer College of Chiropractic, Davenport, Iowa.) |

Willard Carver had been a friend and sometimes legal counsel for D.D. Palmer, but he graduated from the Charles Ray Parker School of Chiropractic in Ottumwa, Iowa, in 1906, rather than from PSC. Carver referred to himself as the “constructor” of chiropractic, as opposed to B.J. Palmer being called the “developer,” and he referred to his college in Oklahoma City as the “Science Head,” in contrast to B.J. Palmer’s “Fountainhead.” Carver went on to preside over four separate institutions in Oklahoma City, Washington, D.C., New York, and Denver, which eventually merged with other schools. When the new Oklahoma legislature convened in 1907, Carver introduced the first bill to legalize chiropractic in that state (Fig. 3-4). It did not pass. For years, his training as a lawyer would be used when called on to testify for chiropractic in legislative hearings. Carver authored 18 books and exerted a great influence on the new profession.

|

| Fig. 3-4 Willard Carver fighting for chiropractic legislation in Oklahoma. (Painted by Robert Lawson. Courtesy Chiropractic Centennial Foundation, Davenport, Iowa.) |

John Howard, a 1905 graduate of the PSC, resigned from the PSC faculty in 1906 and started a competing school in the same building in which D.D. Palmer first practiced and formulated his theory of chiropractic. Howard moved his National School of Chiropractic (NSC) to Chicago in 1908, where it was able to take advantage of its proximity to Cook County Hospital to offer observation of surgeries. By 1912 the school was offering physiological therapeutics and had several medical physicians on its faculty. In 1914, Howard sold the NSC to one of its faculty, William Schultz, M.D. Under Schultz’s leadership, NSC became the major broad scope chiropractic influence. It was eclectic in its approach, and it offered physiologic therapeutics, naturopathy, and various other adjunctive procedures, in strong contrast to B.J. Palmer’s straight, hands-only approach to chiropractic.

Tullius Ratledge, another early chiropractic educator, heavily influenced the development of the profession in California. He moved his school from Kansas to California in 1911 and continued as President of the Ratledge College of Chiropractic until he sold it in 1951 to Carl Cleveland, Sr. Ratledge served 75 days in jail in California in 1916 rather than pay his fine. In one year alone, 450 chiropractors were jailed in California for practicing medicine without a license. 9 Ratledge was active in the 1922 California referendum, which won licensure for chiropractors. California Governor Friend Richardson pardoned all chiropractors in jail at the time of the referendum’s passage, declaring they had been unjustly accused.

Sylva Ashworth, the last pioneer in this attenuated list, graduated from the PSC in 1910 and became active in Nebraska state politics, serving on the first chiropractic board of examiners for that state. Her daughter, Ruth, and son-in-law, Carl Cleveland (1917 PSC graduates), started the Central College of Chiropractic in Kansas City in 1922, renaming it the Cleveland Chiropractic College in 1924. In 1951, Carl Cleveland took leadership of the Ratledge College of Chiropractic, renaming it the Cleveland Chiropractic College of Los Angeles in 1955. Sylva’s great-great grand-daughter, Ashley, became the world’s first fifth-generation chiropractor, and she currently serves as an administrator and faculty member at Cleveland Chiropractic College–Kansas City (Fig. 3-5, A-G).

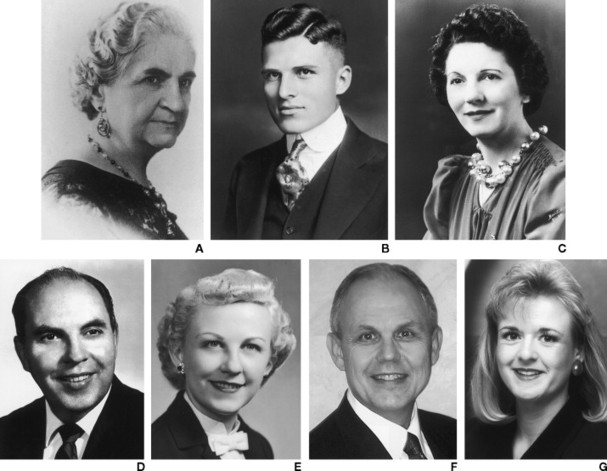

|

| Fig. 3-5 The first five-generation chiropractic family. A, Sylva L. Ashworth, PSC 1910; B, Carl S. Cleveland, Sr., PSC 1917; C, Ruth R. (Ashworth) Cleveland, PSC 1917; D, Carl S. Cleveland, Jr., CCC 1942; E, Mildred G. Cleveland, DC, CCC 1954. F, Carl S. Cleveland, III, CCC 1975. G, Ashley E. Cleveland, CCC 1995. (Courtesy Cleveland Chiropractic College, Kansas City, Mo.) |

The fifth major event—actually, a series of events—that chronicle chiropractic’s struggle for state licensure, was an effort that would require diligence for over 60 years. Politics, both that of organized medicine against chiropractic and that of “mixer” and “straight” chiropractors against each other, * extended the process in the United States from before 1913 when the first state, Kansas, licensed chiropractors, until 1974, when legislation for chiropractic was passed in Louisiana. 10 The years between are filled with hundreds of stories of tragedy and triumph.

*“Mixers” have been historically referred to as chiropractors who use ancillary methods to treat their patients in addition to the chiropractic adjustment. These methods may include electrotherapy, hydrotherapy, acupuncture, acupressure, and vitamin therapy. The disagreement over whether these ancillary procedures are within the purview of the chiropractor has formed the basis for debate between the “straights” and “mixers.” In reality, however, this bimodal separation of chiropractors has never existed. In a statistical sense, there is a “normal” distribution, with most chiropractors falling somewhere in the middle (see Chapter 2 for further discussion).

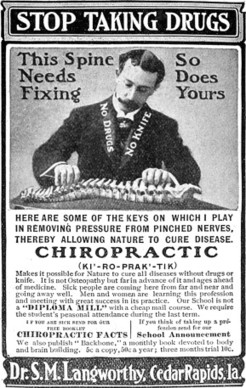

Chiropractors in California provided a striking example of success after years of struggle. As previously noted, more than 450 California chiropractors went to jail rather than pay a fine. Often, they would set up their portable adjusting tables and proceed to treat their patients in jail (Fig. 3-6, A).