Iatrogenic Disorder

Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency

Primum non nocere

I will follow that system of regimen which, according to my ability and judgment, I consider for the benefit of my patients, and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous.

Hippocratic Oath1

The ancient Hippocratic appeal to physicians to “first, do no harm” has a powerful attraction among members of the health care professions and in the popular imagination. After all, if a physician’s job is to heal, should not patients receive benefit from a physician’s ministrations and not further injury? Unfortunately, the physician—as a professional, as a healer, and as a human being—must occasionally face the specter of inadvertently causing harm to a patient.

Chiropractic has come under increased scrutiny as a result of its widespread popularity and its recent entry into the health care mainstream. Considerable progress has been made in interprofessional relations between chiropractors and medical physicians in recent years, but the adversarial climate of the past has not entirely disappeared. In this context, the possibility of adverse reactions to chiropractic treatment is a politically and emotionally charged issue. In certain cases, the popular media and some biomedical journals have inflamed the issue by emphasizing the rare negative reactions to spinal adjustment/manipulation and evaluating its risks in isolation rather than comparing them with the risks of common medical treatments for similar problems.

Most chiropractors perform thousands of treatments annually without any serious complications, and they observe that many patients benefit greatly from adjustment/manipulation. Many of these therapeutic successes occur after more aggressive therapies, medications, and surgery have failed. Such personal experience with the safety and effectiveness of spinal adjustment/manipulation can lead individual chiropractors to devalue reports of adverse reactions. The incongruity between the positive personal experience of chiropractors using adjustment/manipulation and recurring negative stories about its alleged dangers sets the stage for a chiropractic paradox:

• According to certain medical authors, chiropractic spinal adjustment/manipulation has a very limited role to play in conventional health care, if any. 2 In some cases, particularly those involving the cervical spine, some medical authorities consider the procedure “too risky to perform.”3

• Nonetheless, millions of people receive chiropractic spinal adjustment/manipulation each year, without apparent harm and with apparent benefit.

• Furthermore, the vast majority of doctors of chiropractic (DC) and non-DC practitioners of manual medicine have never personally experienced a serious complication during treatment. Most chiropractors view adjustment/manipulation as safe and noninvasive, and they frequently perform the procedure on family members and loved ones and receive it themselves with hardly a thought of potentially hazardous complications.

• In recent years, several reviews of the scientific literature from leading authorities have agreed that many chiropractic methods for treating neck-related conditions are safe, effective, and appropriate. For example, in a 1996 report published by the RAND Corporation, 4 a multidisciplinary expert panel found that adjustment/manipulation and mobilization of the cervical spine were appropriate treatments for patients with many common categories of neck pain and headache. In a 2001 systematic review of the scientific literature, 5 medical experts at the Duke University Evidence-Based Practice Center found cervical manipulation an appropriate treatment for both tension-type headaches and cervicogenic headaches (a specific category of headaches associated with neck symptoms). The Duke report also noted that “adverse effects are uncommon with manipulation and this may be one of its appeals over drug treatment.”

It is crucial that the risks of chiropractic procedures not be evaluated in a clinical vacuum, with inappropriate emphasis on adjustment/manipulation’s perceived risks and corresponding underemphasis on the considerable scientific evidence favoring its safety and effectiveness. The solution to the chiropractic paradox lies in the answers to two key questions: how inherently risky is spinal adjustment/manipulation, and how do its risks and benefits compare with other conventional treatments for similar conditions?

CERVICAL ADJUSTMENTS: CONSERVATIVE CARE OR A RISKY GAMBLE?

The safety of cervical spine adjustment/manipulation has been questioned more frequently than any other commonly applied chiropractic procedure. Reports of serious complications from neck adjustment/manipulation have intermittently appeared in the medical literature since at least 1934. 6 The issue has been increasingly discussed in the popular media in the last decade. However, in early 2002, worries reached a crisis level in the Canadian press after a group of 60 Canadian neurologists issued press releases calling for a ban on neck manipulation. 7 Articles in newspapers published across Canada quoted the neurologists as asserting that the chiropractic procedure “causes strokes and crippling injury with alarming frequency.”8

To most chiropractors, this article was deeply disturbing, not only for its overall alarmist tone, but also for its publication of blatantly inaccurate information. For example, it quoted one neurologist as saying that “the latest figures” estimating the risk of strokes from neck manipulation “have put it a little closer to one in 5,000 [manipulations].” However, one potentially positive effect of this story was that the need for chiropractors to fully inform themselves about the potential risks of neck adjustment/manipulation was highlighted. With accurate, up-to-date information, chiropractors can institute preventive measures to decrease risk to patients, as well as provide reasoned responses to journalists, patients, and medical colleagues who are concerned that chiropractic treatment is unacceptably hazardous.

Mechanisms of Stroke from Cervical Adjustment/Manipulation

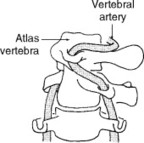

The most likely mechanism of stroke from cervical adjustment/manipulation involves injury to the vertebral artery as it courses through the transverse foramina of the upper cervical vertebrae into the base of the skull. Between the first two cervical vertebrae, the vertebral artery makes a sharp bend upward and laterally to enter the transverse process of the atlas vertebra. The artery is relatively fixed to the transverse processes by fibrous tissue at this point and is less freely movable.

The vertebral artery emerges from the transverse process of atlas and winds posteriorly and laterally around the posterior arch of atlas. Then the artery ascends into the foramen magnum and joins with its counterpart to form the basilar artery. This vertebrobasilar (VB) system comprises the main blood supply of the brain stem.

Vigorous rotation of the neck may traumatize the vertebral artery along its course, most likely between atlas and axis or atlas and occiput (Fig. 26-1). This trauma may cause a dissection or tearing of the inner artery wall, or the trauma may lead to formation of a blood clot that can break free and lodge in one of the other ascending blood vessels. Either event can result in a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or ischemia to the brainstem. Alternately, the force of rotation may cause vasospasm in one vertebral artery. If preexisting arteriosclerosis or a developmental anomaly has compromised flow in the contralateral artery, brainstem ischemia may also occur.

|

| Fig. 26-1 The stretch applied to the vertebral artery with cervical rotation is a possible mechanism for vertebrobasilar stroke from adjustment/manipulation. (From Terrett AGJ: Current concepts in vertebrobasilar complications following spinal manipulation, West Des Moines, Iowa, 2001, NCMIC Group. Used by permission.) NCMIC Group |

Cervical adjustment/manipulation is not the only mechanism to initiate this type of injury. The literature contains numerous reports of similar vascular accidents resulting from common medical procedures, such as administering anesthesia during surgery9,10 or during neck extension for radiography. 11 Cases of vertebrobasilar accidents (VBA) have been reported, which apparently occurred during normal activities such as swimming, yoga, stargazing, overhead work, 12 sexual intercourse, 13 and even during sleep. 14“Beauty parlor stroke,” caused by cervical hyperextension over a sink while washing the hair, is also well documented. 15 Cases of spontaneous VBAs, with no apparent precipitating event, have been reported as well. 16,17

With the increasing availability of noninvasive imaging technologies, in particular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), many patients who present with subtle manifestations of the condition are now being diagnosed as having a VB dissection. Although still considered an extremely rare form of stroke, the number of diagnosed cases of VBA has increased notably in recent years.

Based on the association between VBA and seemingly trivial stress to the artery, it is reasonable to conclude that this condition has a multifactorial etiologic aspect, likely involving both genetic and environmental factors. Several inheritable connective tissue disorders are associated with an increased risk of vertebral and carotid artery dissection. 18 These disorders include:

• Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) type IV, an inheritable disorder characterized by weakened linings of the walls of blood vessels and the intestine. Unlike more common types of EDS (sometimes referred to as the “rubber-man” disease), type IV EDS is associated with minimal skin and joint hyperextensibility but is associated with a notable tendency toward easy bruising.

• Marfan’s syndrome, a generalized disorder of connective tissue with skeletal, ocular, and cardiovascular manifestations. Characteristically, the affected person is tall and thin with long extremities, with an arm span greater than the height. These individuals often have long, thin, and hyperextensible fingers and commonly have a marked spinal kyphosis, deformities of the sternum, or both, similar to pectus excavatum (“funnel chest”) or pectus carinatum (“pigeon breast”).

• Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), a generalized inheritable disorder of the connective tissue associated with abnormal fragility of the skeleton, easy bruising, abnormal dentition, and blue sclerae. Milder cases of OI (type I) can also be associated with loose joints, low muscle tone, and a tendency toward spinal curvature.

Several recent studies have suggested a role for an infectious trigger in cervical artery dissections. One recent case-control study19 established a recent respiratory tract infection as a possible risk factor of spontaneous carotid and vertebral artery dissections, a possibility supported by the seasonal variation in this condition, with a peak occurrence in the autumn. 20

Other recent studies have suggested that mildly increased plasma levels of the amino acid homocystine (hyperhomocystinemia) might also be a risk factor for cervical artery dissections. One study21 found that a series of 26 patients who had suffered a cervical artery dissection had higher plasma homocystinemia levels than controls, findings that were found to be statistically significant.

Mild to moderately increased levels of homocystine in the blood plasma (observed in 5% to 7% of the adult population) have been associated with an increased risk for a variety of cardiovascular diseases. This condition may be caused by congenital defects involving production of the enzyme 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR). A chronic dietary deficiency of folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 may also be an important cause.

Treatment of hyperhomocystinemia consists of vitamin supplementation and nutritional intervention, including direct supplementation with folic acid, vitamin B12, and pyridoxine. A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products and reduced in saturated and total fat has been shown to lower serum homocystine.

Strokes of the posterior cerebral circulation (involving the posteriorly located VB arteries rather than the anteriorly located carotid arteries) usually present with signs of brainstem injury, such as severe nausea and vomiting, visual problems, or vertigo. Strokes of the posterior circulation also result in Wallenberg’s syndrome, in which loss of pain and temperature of the face occurs on the ipsilateral (same) side of the lesion and of the body on the contralateral (opposite) side. Extreme cases can demonstrate the locked-in syndrome, during which the patient is conscious but completely paralyzed except for eye movements.

Although the outcome of VB strokes can be catastrophic, it is important to note that only a minority of these strokes are fatal or result in such severe disability. In 2001, Terrett22 summarized the outcomes of the 255 cases of VBAs after spinal adjustment/manipulation reported in the worldwide medical literature from 1934 to 1999. Approximately 30% of the cases resolved completely or almost completely. Death occurred in 37 cases (15%), and 9 cases (4%) resulted in the locked-in syndrome with tetraplegia. In a retrospective analysis of hospital records, Saeed and collegues23 followed up on 26 patients who suffered VBA from a variety of causes. The authors found that 83% had a favorable outcome and the recurrence rate was low. A poor prognosis was usually associated with bilateral dissection and intracranial VB dissection accompanied by subarachnoid hemorrhage.

It has been proposed that the rate of strokes after adjustment/manipulation may be significantly underreported in the literature. 24 However, equally likely is that the cases resulting in death or major neurologic deficits are proportionally overreported in the literature. Serious and impressive cases appear more likely to warrant description in a published case report.

INCIDENCE OF STROKE FROM ADJUSTMENT/MANIPULATION: A SUMMARY OF STUDIES

Every reliable published study estimating the incidence of stroke from cervical adjustment/manipulation agrees that the risk is less than 1 to 3 incidents per 1,000,000 treatments and approximately 1 incident per 100,000 patients who are being treated with cervical adjustment/manipula tion (Table 26-1). When discussing a numerical estimate of this risk, it is especially important to make a clear differentiation between the number of chiropractic patients and the number of chiropractic visits. Even some authorities on this subject have become confused because some studies have attempted to estimate the risks per visit, while other studies discuss the risk experienced by each chiropractic patient over an entire course of care, which may include a significant number of visits.

| CVA, Cerebrovascular accident; VBA, vertebrobasilar accident. | ||

| Source | Methods | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Dvorak28 | Survey of 203 members of the Swiss Society of Manual Medicine | One serious complication per 400,000 cervical adjustment/manipulations; no reported deaths |

| Jaskoviak25 | Report based on clinical files of the National College of Chiropractic Clinic | No cases of vertebral artery injury or stroke in 5 million cervical adjustment/manipulations in a 15-year period |

| Patijn29 | Review of computerized registration system in Holland | Overall rate of complication of 1 in 518,000 adjustment/manipulations |

| Haldeman31 | Extensive literature review to formulate practice guidelines | 1–2 incidences of stroke per million adjustment/manipulations |

| Carey32 | Review of Canadian malpractice figures | 1 CVA per 3,000,000 neck adjustment/manipulations |

| Klougart34 | Survey of Danish Chiropractors’ Association members, cross-referenced of CVA occurrences from published cases, official complaints and insurance data | 1 CVA per 1,320,000 cervical spine treatment sessions and 1 CVA per 414,000 cervical spine sessions using rotation techniques in the upper cervical spine |

| Haldeman, Carey et al33 | Updated review of Canadian malpractice figures | Risk of CVA 1 in 5.85 million cervical adjustment/manipulations, 1 in 1430 chiropractic practice years, and 1 in 48 chiropractic practice careers |

| Rothwell35 | Case-control study, based on review of hospital records for VBA and insurance billing records for chiropractic visits | 1 CVA per 3–4 million chiropractic cervical visits; “for every 100,000 persons aged <45 years receiving chiropractic, approximately 1.3 cases of VBA attributable to chiropractic would be observed within 1 week of their manipulation.” |

Several studies have documented large numbers of cervical adjustment/manipulations without any reports of stroke or major neurologic complication. One report25 documents approximately 5 million cervical adjustment/manipulations performed at the National College of Chiropractic Clinic from 1965 to 1980 without a single case of vertebral artery stroke or serious injury. Henderson and Cassidy26 reported a survey done at the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College outpatient clinic in which more than 500,000 treatments were given over a 9-year period, again without serious incident. Eder27 offered a report of 168,000 cervical adjustment/manipulations over a 28-year period without a single significant complication.

A survey of 203 members of the Swiss Society for Manual Medicine28 found a practitioner-reported rate of 1 serious complication per 400,000 cervical manipulations, without any reported deaths, among approximately 1.5 million cervical manipulations. Notably, these practitioners were nonchiropractors who received an average of approximately 38 days of training in manipulation. This survey represents the highest incidence rate of complications from cervical manipulation reported in the literature.

In another survey based on a computerized registration system in Holland, Patijn29 found an overall rate of 1 complication in 518,886 manipulations. Other experts on adjustment/manipulation30 have published opinions that the risk of stroke from cervical adjustment/manipulation is “two or three more-or-less serious incidents.” per million treatments.

After performing an extensive literature review to formulate practice guidelines, the authors of a consensus document31 concurred that, “the risk of serious neurological complications [from cervical adjustment/manipulation] is extremely low, and is approximately one or two per million cervical manipulations.”

Carey, 32 the president of the Canadian Chiropractic Protective Association (CCPA), Canada’s largest chiropractic malpractice insurance carrier, reviewed claims of CVA from chiropractic adjustment/manipulation in Canada between 1986 and 1991. Carey estimated that approximately 50,000,000 neck adjustment/manipulations were performed in Canada during that period, 13 of which resulted in significant CVA incidents, with no reported deaths. This article suggests that the incidence of CVA from neck adjustment/manipulation is approximately 1 incident per 3,000,000 neck adjustment/manipulations.

These figures were updated and republished in 200133 and found that 43 cases of neurologic symptoms after cervical adjustment/manipulation appeared in the malpractice database of the CCPA between 1988 and 1997. Based on a survey questionnaire, estimates suggest that chiropractors covered by the CCPA performed approximately 134.5 million cervical adjustment/manipulations over that same time period. Based on these data, the authors concluded that the likelihood that a chiropractor will be made aware of an arterial dissection after cervical adjustment/manipulation is approximately 1 in 8.06 million office visits, 1 in 5.85 million cervical adjustment/manipulations, 1 in 1430 chiropractic practice years, and 1 in 48 chiropractic practice careers.

Klougart and Colleagues’ 10-Year Danish Study

In one of the best-documented studies to date, Klougart and collegues34 sought to identify the total number of CVAs related to chiropractic adjustment/manipulation that occurred in Denmark over a 10-year period. All members of the Danish Chiropractors’ Association were surveyed, and the members’ reports of CVA occurrences were cross-referenced with published cases, official complaints, and insurance data. The authors then estimated the total number of neck adjustment/manipulations that chiropractors performed over the same time period from survey responses that were cross-referenced with insurance reimbursement data. Results indicated five cases of “irreversible CVA after chiropractic treatment.” occurred in Denmark between 1978 and 1988 in the course of 6,600,000 cervical spine treatment sessions. Klougart estimated a risk of 1 CVA per 1,320,000 cervical spine treatment sessions and 1 CVA per 414,000 cervical spine sessions using rotation techniques in the upper cervical spine.

Rothwell and Colleagues’ 5-Year Canadian Study with Statistical Control

A recent important population-based study published in the journal Stroke35 has received much publicity, though its conclusions have been frequently misinterpreted. Rothwell and colleagues reviewed all hospital billing records in the province of Ontario between 1993 and 1998, and found a total of 582 VBA cases from all causes. Presumably, this search identified all cases of VBAs in this population because medical costs in Ontario are all recorded and paid by the provincial health plan; however, retrospective reviews of billing records are problematic because the diagnoses listed in billing records are often incomplete or inaccurate. Each VBA case identified was age and sex matched to four controls from the Ontario population who had no history of stroke. Public health insurance billing records were used to document use of chiropractic services for both the CVA patients and the four controls during the year before at the date of the VBA onset.

Based on the chiropractic billing history, the authors found that 27 of the 582 VBA cases were believed to have had a chiropractic cervical treatment in the year previous to the stroke. Of these, four individuals visited a chiropractor the day immediately preceding the VBA, five in the previous 2 to 7 days, three in the previous 8 to 30 days, and 15 in the previous 31 to 365 days. Compared with the controls, an increased incidence of VBA occurred among patients who saw a chiropractor within 8 days before the VBA event, but a decreased incidence of CVA occurred among patients who saw a chiropractor 8 to 30 days before the reference date.

This study found no correlation between recent chiropractic visits and VBAs in patients over age 45. However, patients under age 45 were five times more likely than the controls to have had a chiropractic neck treatment within the week before the VBA. Patients with VBA were also five times more likely to have had three or more chiropractic visits with a cervical diagnosis in the month preceding the VBA. Some media outlets and several chiropractic critics reported these findings with alarm.

It is important that the Rothwell group’s findings be placed in proper perspective. Analysis of their raw data reveals that their findings relating cervical adjustment/manipulation to an increased incidence of VBA are based on fewer than five cases that occurred among the study’s entire population over a 5-year time frame.

Stated another way, the data from the Rothwell and colleagues study show that the 11.5 million people of Ontario (approximately one third the population of Canada) had approximately 50 million chiropractic visits over the 5 years analyzed, some 15 to 20 million of which involved a cervical adjustment/manipulation. Among this population, approximately five incidences of VBA occurred that were statistically related to cervical adjustment/manipulation. Therefore this study actually found that the risk of a chiropractic-related VBA for the entire population was approximately 1 per 10 million chiropractic office visits and on the order of 1 per 3 to 4 million chiropractic cervical visits. “Despite the popularity of chiropractic therapy,” the authors wrote in their conclusion,

[The] association with stroke is exceedingly difficult to study. Even in this population-based study the small number of events was problematic…. Our analysis indicates that, for every 100,000 persons aged <45 years receiving chiropractic, approximately 1.3 cases of VBA attributable to chiropractic would be observed within 1 week of their manipulation.”

Even if one concedes that a statistically significant correlation exists between cervical adjustment/manipulation and VBA in the under-45 age group, correlation does not necessarily imply causation. Accumulating evidence suggests that sudden onset of headache pain, neck pain, or both may be an early indication that a VBA has occurred or is imminent. That many of these patients might present to a chiropractor for evaluation, treatment, or both of such symptoms appears likely. Given the established demographic patterns of chiropractic patients, also likely is that patients in the under-45 age group would be more likely than older patients to see a chiropractor for such symptoms. It would have been informative if the authors of this study had performed a similar study looking at how frequently patients of VBA saw any health care practitioner for a cervical-related diagnosis in the days or weeks preceding the stroke. Such a study might help clarify the early warning signs of this enigmatic condition and help all types of health care practitioners recognize a VB dissection before it becomes irreparable.

To their credit, Rothwell and colleagues recognized the limitations of this study and were duly cautious to not conclude that cervical adjustment/manipulation causes VBA. In contrast, an accompanying editorial36 by a neurologist went much further, noting that, “For neurologists there is little doubt that chiropractic manipulation can cause vertebral artery dissection.” As previously discussed, any such certainty—at least for the neurologists practicing in Ontario—would have been based on an average of a 1 case among some 100 annual cases of VB stroke. The same editorial goes on to state that this study demonstrated that the incidence of VBA dissection is “far more than the 1 case per million generally believed.” However, this one-in-a-million figure is usually based on the risk of serious complications per chiropractic visit, or per cervical adjustment/manipulation. As previously noted, this study actually found that the risk of a chiropractic-related VBA for the entire population was on the order of 1 per 3 million chiropractic cervical visits. Even in the apparently high-risk under-45 age group, the risk per cervical visit is still consistent with the widely quoted one-in-a-million figure.

Other data appearing in the Rothwell study found that only 2.1% of the 582 cases of VBA they identified had at least one cervical chiropractic visit in the month previous to the stroke versus 1.7% of controls that had a chiropractic cervical visit in the same time frame. In other words, VBA was correlated with a recent chiropractic neck treatment in only 0.4% of the 582 VBA cases they identified. These figures contrast sharply with the claim previously made by Norris and colleagues37 that, “stroke resulting from neck adjustment/manipulation occurred in 28% of our cases [of VBA].” This data was collected from a survey of neurologists who treated patients of VBA. However, Norris’ criteria for inferring this claimed relationship—much less their basis for presuming causality—have never been adequately described.

Relative Consistency of Data on Stroke

Taken together, the best quality studies form a remarkably consistent pattern regarding the frequency of stroke from cervical adjustment/manipulation. In summary, a reasonable estimate of the risk of stroke from cervical adjustment/manipulation ranges between 1 in 400,000 to 1 in 5 million cervical adjustment/manipulations performed, and the risk of death from adjustment/manipulation-induced stroke is between 1 in 4 million to less than 1 in 10 million cervical adjustment/manipulations.

Research Challenges

Researching this issue more thoroughly presents many difficulties. Ideally, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) should be used to explore prospectively the relation between neck adjustment/manipulation and stroke. However, a reliable RCT requires the researcher to follow three times as many patients as the reciprocal of the expected reaction rate so as to be 95% confident that a single reaction will occur. 38 Thus, based on the best estimates currently available, an RCT would require observing 1.5 to 15 million neck adjustments to be valid. The time, money, and personnel required for such a prospective study would appear prohibitive.

Retrospective case studies may be the only feasible way to study this phenomenon. Unfortunately, many published case reports have serious drawbacks. Some reports are poorly documented and fraught with serious questions regarding the cause-and-effect relationship between the adjustment/manipulation and stroke. Other reports have misrepresented the profession of the practitioner, using the term chiropractic despite the fact that the involved practitioner was not a chiropractor. 39

REDUCING THE RISKS

Although all the available evidence makes clear that stroke after adjustment/manipulation is quite rare, this is no reason for complacency on the part of chiropractors. Strokes from adjustment/manipulation appear to fall into three patterns: manipulating the high-risk patient, inappropriate manipulative technique, and strokes occurring in patients who apparently who were unable to have been previously identified as being high risk.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree