Duke Headache Evidence Report

Repetitive Stress Disorders

Notwithstanding the fact that chiropractic has existed as a formal profession for over a century, most of the rigorous, systematic research that has been recognized to support this form of health care has emerged in just the past 25 years. In 1975—a turning point for chiropractic research—Murray Goldstein of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicable Diseases and Stroke (NINCDS) conducted and published an assessment of the research status of spinal manipulation; the results were not encouraging. Goldstein’s report concluded that there was little rigorous outcomes research in support of chiropractic intervention for back pain and other musculoskeletal disorders. 1

In addition to the insufficient numbers of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or observational studies of sufficient quality published in the established medical journals, early outcomes trials suffered from any number of significant design flaws, such as the following:

• Often lacking an adequate description of adjustment/manipulation, these trials commonly described mobilization (i.e., noncavitating manual movements of joints) rather than manipulation. Furthermore, the methods often lacked adequate descriptions to permit their precise replication.

• Ambiguity existed in the clinical characterizations of the sample population.

• Qualifications of those administering treatment were not reported, whether they were chiropractors, osteopaths, physical therapists, or medical physicians.

• Physician-patient contact times were not uniform across compared groups.

• Sample sizes were often too small to approach statistical significance.

• Failure to observe or control baseline characteristics was common.

• Experimental bias was often introduced into the trial and was often implicit in the recruitment process.

• In a laboratory setting, under tightly controlled conditions, the interventions tended to be very individualized and as such were difficult if not impossible to generalize to the clinical situation.

Nearly 30 years after the NINCDS conference, dramatic changes are in evidence regarding data demonstrating the efficacy of spinal adjustment/manipulation. Regarding low back pain as assessed by government agencies in the United States, 2 Canada, 3 Great Britain, 4 Sweden, 5 Denmark, 6 Australia, 7 and New Zealand, 8 one could argue that chiropractic care appears have vaulted from last place to first as a treatment option.

For example, Clinical Practice Guideline 14—Acute Low Back Problems in Adults, a 1994 assessment of low back pain by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR), an agency of the U.S. government, placed adjustment/manipulation in the first two treatment options (among 22 different types of interventions) to be considered, together with the use of analgesics and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). 2 Commenting on this landmark report in an Annals of Internal Medicine editorial, Marc Micozzi stated:

The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) recently made history when it concluded that “…spinal manipulation hastens recovery from acute low back pain and recommended that this therapy be used in combination with or as an alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs….” Perhaps most significantly, the guidelines state that “ …spinal manipulation offers both pain relief and functional improvement.”9

The British guidelines lauded that “there is considerable evidence that manipulation can provide short-term symptomatic benefits” in certain patients4; the Danish report echoed this sentiment by declaring that “manual treatment can be recommended for patients suffering from acute low back symptoms and functional limitations of more than 2 to 3 days’ duration.”6

This chapter describes the more recent evolution of musculoskeletal disorders research, with primary emphasis on back and neck pain, most types of headache, and pain in the extremities. The focus is on research since the defining moment of the 1975 NINCDS conference. Key events influencing the profession’s reversal of fortune are identified, and recent studies, which on balance clearly demonstrate the benefits of chiropractic intervention are discussed.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Through the 1920s the chiropractic profession remained largely unfamiliar with research methodology, relying primarily upon testimonials from cured patients to document its effectiveness. 10 This was the era when allopathic medicine was just beginning to follow an experimental research regimen that had been proposed by Claude Bernard in 1865. 11 Chiropractic research was significantly hampered at this time and for many decades thereafter by staunch opposition from the American Medical Association (AMA). 12

In the early years of the profession, most chiropractic professional schools were proprietary and depended upon tuition and clinical fees for survival. Under those conditions, little research was possible except for some case studies, many of which provided invaluable clinical insights. Many of these early investigations followed the interests of B.J. Palmer and the Palmer School of Chiropractic, beginning with the establishment of a “spinographic” laboratory in 1910, in which it was believed that radiographs would provide the opportunity for detecting spinal displacements. 13 After the introduction of this technology, it was asserted by some that patient recovery increased dramatically. 14 Palmer proposed that, “spinography does more than read subluxations, it proves the existence, location, and degree of exostosis, ankylosis, abnormal shapes and forms, all of which may prevent the early correction to normal position of the subluxation.”15 The growing interest in radiography was reflected by the introduction of full-spine radiography by Thompson, 15 later refined in 1931 by the use of a single film. 13

H.E. Crowe’s description of the term “whiplash” in 1928 introduced the importance of the soft tissue injury. Whiplash refers to soft tissue injuries in the vicinity of the cervical spine, often caused by automobile accidents. 16 Although now accepted as a medical term, the condition is often associated with litigation17 and suffers from a scanty literature base. 18

Largely through the efforts of Joseph Janse and Fred Illi, the sacroiliac joint became the next key focus in chiropractic research. Starting in 1943 in the laboratory at the Institute for the Studies of Statistics and Dynamics of the Human Body in Geneva, Switzerland, Illi’s ongoing work provided insight into the functioning of the sacroiliac joint as a synovial articulation required for fully upright bipedal locomotion. 19

During World War II, European chiropractic researchers developed the practical spinal analysis, called motion palpation, as a collective work. A group of Belgian chiropractors, including Marcel and Henri Gillet, Maurice Liekens, Fenande De Mey, Henri Poeck, and Paul de Borchgrave, drew upon chiropractic pioneer O.G. Smith’s theory that the vertebral joint has both a circumscribed field and center of motion that become offset when a subluxation occurs. 20 Publications began to describe the methods available to help the practitioner find and demonstrate the evident changes in mobility of the vertebral and sacroiliac articulations before and after an adjustment. 21,22

By the mid-1970s chiropractic adjustment/manipulation began to be covered under Medicare in response to political efforts by chiropractic practitioners and patients. In a 1974 report, a Senate subcommittee recommended that “this would be an opportune time for an ‘independent, unbiased’ study of the fundamentals of the chiropractic profession.” Consequently, Congress authorized up to $2 million of the 1974 Department of Health Education and Welfare (DHEW) appropriation for that purpose. 10

Organized and chaired by osteopathic physician Murray Goldstein, Associate Director of NINCDS, the conference topic was termed spinal manipulation in order to emphasize the common ground shared by the multidisciplinary group of leading clinicians and scientists who met for 3 days in Washington. Although the conference failed to deliver a consensus as to the indications, contraindications, and precise scientific basis for the results obtained by manipulation of the spine, 1 it did produce the following comments by its organizer, which set the stage for the next 25 years of chiropractic research:

But perhaps of most far reaching importance, the workshop documented that although there are a number of meaningful basic and clinical research questions about manipulative therapy and vertebral biomechanics that are amenable to investigation, there was relatively little quantitative data either in support or in opposition to the several clinical hypotheses….I suspect the NINCDS Workshop cleared the air by demonstrating that there are precise scientific issues relevant to manipulative therapy that deserve research attention. 23

In the years since 1975, the chiropractic profession has heeded this call, producing an extensive body of research.

BACK PAIN RESEARCH

Methods of Measurement

As in other clinical outcomes research, chiropractic investigations require both reproducible and verifiable measurements from multiple points of view involving both the patient and clinician. Box 23-1 illustrates five such perspectives: (1) the results of physical examinations; (2) functional abilities; (3) patient perception regarding pain, satisfaction, duration of complaint, and use of medications; (4) general health and psychosocial assessments; and (5) direct and indirect costs of treatment. All the indices listed have been verified in the literature; use of the measures represented on this list helps to ensure that an outcome study achieves sufficient construct validity.

Box 23-1

CLINICAL OUTCOMES INSTRUMENTS IN CHIROPRACTIC RESEARCH

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Neuologic deficits

Straight-leg raises

FUNCTIONAL OUTCOME ASSESSMENTS

Oswestry back disability index

Roland-Morris low back pain disability questionnaire

Neck disability index

Range of motion

Muscle strength

PATIENT PERCEPTION OUTCOME ASSESSMENTS

Pain

Visual analog scale (VAS)

Verbal rating scale (VRS)

Behavioral rating scale (BRS)

McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ)

West Haven-Yale multidimensional pain inventory (WHYMPI)

Patient satisfaction

Patient diary; duration of episode

Use of medications

GENERAL HEALTH AND PSYCHOSOCIAL ASSESSMENTS

Health-related quality of life

Medical outcomes study short-form general health survey

Sickness impact profile

SF-36

Dartmouth primary care cooperative information project (COOP)

Million behavioral health inventory (MBHI)

Modified Zung depression index

COSTS (DIRECT AND INDIRECT)

All visits to provider

Prescription and nonprescription drugs or supplements

Laboratory costs

Diagnostic imaging

Referral to specialists

Hospital costs

Workdays lost by patient

Retraining for replacement labor

Caregiver to assist in domestic duties

Iatrogenic events

Legal and malpractice costs

At the same time, outcomes research (particularly involving physical methods) is tarnished by what appears at first glance to be a conundrum. Table 23-1 lists outcome studies in order of decreasing rigor, from the most fastidious, demanding (and costly) RCT to anecdotes arising from everyday clinical experiences. At first glance, one might assume that the most controlled investigation (the clinical trial) would yield the most useful information. Indeed, the clinical trial is often referred to as the “gold standard”24 in clinical research. Paradoxically, because the double-blind study is so controlled, this most rigorous member of the clinical research hierarchy presents its own difficulties in its generalizability:

• The characteristics of its own experimental patient base (including co-morbidities*) may differ significantly from those of the individual presenting complaints in the doctor’s office.

*Co-morbidities are conditions existing simultaneously in a patient.

• Potentially important ancillary treatments are restricted, screening out conceivably significant and perhaps unidentified elements that occur in the natural setting of the patient’s visit to the physician.

• Outcome results chosen may not necessarily be those used to evaluate a patient’s welfare under care of an actual physician.

• Experimental groups may not be large enough to reach statistical significance, even though the clinical effect may be real in many individuals.

| Design Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

1. Randomized clinical trial 2. Prospective (cohort) study 3. Retrospective study 4. Cross-sectional study 5. Case control study 6. Single-subject case series 7. Case report 8. Anecdotes | Defined treatment to one group; placebo or sham to second (placebo) Defined treatment to one group, no control; blank or sham group Study performed after treatment (many cases) Study of all subjects performed at one point of time After response of one case and matched control(s) over time After response of one case over time Detailed report on one single case Recollections of case responses, lacking details of case reports |

Thus experimental designs at the “low” end of the spectrum (i.e., anecdotes, single case reports) offer their own form of generalizability, although they are of an uncontrolled and often confounded nature. Again, this does not mean that they fail to provide clinical significance.

Ideally, to support a particular type of intervention, what is needed are research results from both ends of the hierarchy shown in Table 23-1, to capture both the rigor and generalizability sought in clinical documentation. It is, after all, material from the anecdotes and clinician’s office that provide the impetus—the inspiration—to design and conduct a RCT in the first place (see Chapter 22).

Clinical Trials on Back Pain

Approximately 50 clinical trials including spinal adjustment/manipulation can be identified; a minimum of 25 published in English were confirmed by 1992, 25 the number increasing to at least 34 by 1997, 26 and the balance thereafter. Suffering from the design flaws mentioned previously, the earlier trials tended to suggest only short-term benefits for spinal therapy, eliciting a widespread belief from many quarters that it was beneficial in the alleviation of acute pain, but that there existed insufficient documentation of its efficacy with either severe problems or long-term complications. 2,25,27

Nineteen of the strongest and most prominent clinical trials addressing the role of spinal adjustment/manipulation in the management of low back pain are summarized in Table 23-2. Those published through 1997 were of sufficient validity to be included by Bronfort in the evidence supporting spinal manipulative therapy for back pain26; four remaining trials published after 1997 are listed as well. Collectively, these trials indicate the following:

1. In recent years, there has been a proliferation of publications addressing chronic low back pain, offering sufficient refutation to previous assertions that the benefits of adjustment/manipulation are limited to acute cases.

2. Increasing recognition is given to using more objective, reproducible outcome measures such as those proposed in Box 23-1.

3. The difference between manipulation and mobilization seems to have been appreciated, with the inclusion of mobilization as a discrete arm of the clinical trial, often called a “sham” or “mimic” procedure. (The reader should note that “manipulation” and “chiropractic management” have often been used synonymously, sometimes causing serious confusion, in ways outlined in the following section.)

4. In recent studies a trend exists toward specifically identifying practitioners as chiropractors with proper training in adjustment/manipulation, often having the liberty to treat as they would in actual clinical practice. In this manner, the research becomes more pragmatic and gains external validity, helping to solve the conundrum proposed in Table 23-1. (A conspicuous exception to this trend, however, is the Cherkin study, 48 to be discussed later.)

| DC, Doctor of chiropractic; DO, doctor of osteopathy; LBP, low back pain; MD, doctor of medicine; PM, patient modalities; PT, physical therapist; SMT, spinal manipulative therapy; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. | |||||

| Author | Branches | No of Subjects | Subject Complaints | Outcomes | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hadler28 | SMT (MD) | 26 | LBP (acute) | Disability | 2–4 weeks |

| Mobilization (MD) | 28 | ||||

| Glover29 | SMT (MD) and diathermy | 43 | LBP (acute) | Pain | 7 days |

| Detuned ultrasound | 41 | ||||

| Matthews30 | SMT (PT) | 165 | LBP (acute) | Recovery | 2 weeks |

| Heat | 126 | ||||

| MacDonald31 | SMT (DO) and back school | 49 46 | LBP (acute) | Disability | 1–3 weeks |

| Farrell32 | SMT (PT) and mobilization | 24 | LBP (acute) | Recovery | 1–3 weeks |

| Diathermy, exercises, and ergonomic instructions | 24 | Pain | |||

| Koes33,34 | SMT (PT) and mobilization | 36 | LBP (chronic) | Severity main complete | 6 weeks-12 months |

| Massage, exercise, heat, and PM | 36 | Physical functioning | |||

| Analog, MD advice | 32 | Perceived global efficiency | |||

| Detuned modalities | 40 | ||||

| Pope35 | SMT (DC) | 70 | LBP (chronic) | Pain | 3 weeks |

| Massage | 36 | Disability | |||

| TENS | 28 | ||||

| Corset | 30 | ||||

| Waagen36 | SMT (DC) | 11 | LBP (chronic) | Pain | 2 weeks |

| Sham SMT (DC) | 18 | ||||

| Coxhead37 | SMT (DC) | Factorial study with 16 different combinations | LBP (chronic) | Pain | 4 weeks- 4 months |

| Traction | |||||

| Exercise | |||||

| Corset | |||||

| No treatment | |||||

| Triano38 | SMT (DC) | 70 | LBP (chronic) | Pain | 2–4 weeks |

| Sham SMT (DC) | 70 | Disability | |||

| Back school | 69 | ||||

| Giles39 | SMT (DC) | 36 | LBP (chronic) | Pain | 1 month |

| Acupuncture | 20 | Disability | |||

| Medication | 21 | ||||

| Andersson40 | SMT (DO) | 83 | LBP (subacute) | Pain | 1–12 weeks |

| MD therapy | 72 | Disability | |||

| Range of motion | |||||

| Straight-leg raising | |||||

| Skargren41 | Chiropractic | 219 | LBP (chronic; includes patients with neck pain and those with acute undefined problems excluded from study) | Pain | 6–12 months |

| Physiotherapy | 192 | Disability | |||

| General health | |||||

| Cost | |||||

| Meade42,43 | SMT (DC) | 384 | LBP (acute and chronic) | Disability | 6 weeks-3 years |

| SMT (PT) | 357 | Pain | |||

| Analgesics | |||||

| Bronfort44 | SMT (DC) | 11 | LBP (acute and chronic) | Improvement | 1 month |

| GP (MD) | 10 | Work loss | |||

| Zylbergold45 | SMT (PT) and heat | 8 | LBP (acute and chronic) | Pain | 1 month |

| Heat and exercise | 10 | Disability | |||

| Ergonomic instruction | 10 | ||||

| Doran46 | SMT (MD) | 116 | LBP (acute and chronic) | Improvement | 3 weeks- 3 months |

| Physiotherapy | 114 | ||||

| Corset | 109 | ||||

| Analog | 113 | ||||

| Hoehler47 | SMT (MD) | 56 | LBP (acute and chronic) | Pain | 3 weeks |

| Soft tissue massage | 39 | Improvement | |||

| Cherkin48 | SMT (DC) | 122 | LBP (acute and chronic) | Bothersomeness | 4–12 weeks |

| McKenzie (PT) | 133 | Disability | |||

| Booklet (MD) | 66 | Cost | |||

Beginning with the publication of a prospective study by Kirkaldy-Willis and Cassidy in 1985, which represented the first time a chiropractor (Cassidy) coauthored an article published in a medical journal, 49 there has been a consistent trend suggesting that improvement in the main complaint produced by manual therapy at least equals that achieved by standard medical treatment. Moreover, this is accomplished without side effects such as intestinal tract ulcers, erosions of the stomach or intestinal tract lining, 50 or liver and kidney damage associated with the prolonged use of analgesics and NSAIDs. 51

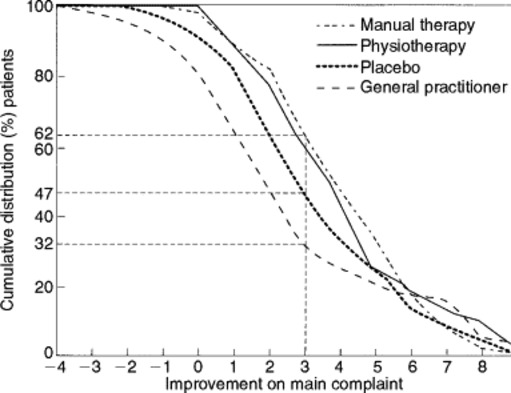

A rather startling result from a trial by Koes and colleagues33 suggests that improvement in the main complaint produced by manual therapy was not only superior to standard medical treatment but also that the latter intervention even failed to keep pace with the placebo group, in which no intervention took place (see Table 23-2; Fig. 23-1).

|

| Fig. 23-1 Low back pain outcomes after various treatments in randomized clinical trial (RCT). Improvement in the main complaint at 6-week follow-up (intention-to-treat analysis). (From Koes BW et al: The effectiveness of manual therapy, physiotherapy, and treatment by the general practitioner for nonspecific neck and back complaints: a randomized clinical trial, Spine 17(1):28, 1992.) |

One of the most important current trends is that, in contrast to earlier trials in which the relief provided by spinal adjustment/manipulation appeared to be short-lived (less than 3 weeks), 28,29,47 some of the more recent, larger trials demonstrate that the beneficial effects of spinal manipulative therapy are uniquely long-lived, persisting for as much as 12 months34,41,42 to 3 years. 42 One problem that has been raised regarding the Meade study, however, is that only 28% of its patients were randomized into the chiropractic branch of treatment. 42

The RAND Appropriateness and Utilization Study

A second facet of musculoskeletal disorders research with regard to back pain and chiropractic can be credited to the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit research and development company that first gained prominence with research for the U.S. military during World War II. In addition to defense, RAND’s research fields include the health sciences, education, applied economics, sociology, and civil justice.

Several years and millions of dollars in the making, the RAND Appropriateness and Utilization Study has sought to provide “a comprehensive set of indications for performing spinal manipulation with low back pain,”52 the guide lines being based upon a review of the literature, appropriateness ratings by both multidisciplinary and all-chiropractic panels of experts, and field studies abstracted from five geographic sites: (1) Portland, Ore; (2) Minneapolis, Minn; (3) Miami, Fla; (4) San Diego, Calif; and (5) Toronto, Ont.

RAND’s literature review of 67 articles and 9 books published between 1952 and 1991 established that chiropractors within the United States performed 94% of all the adjustments/manipulations for which reimbursement was sought, with osteopaths delivering 4% and general practitioners and orthopedic surgeons accounting for the remainder. 52 Support was consistent for the use of spinal adjustment/manipulation as a treatment for patients with acute low back pain and an absence of other signs or symptoms of lower limb nerve root involvement. If minor lower limb neurologic findings or sciatica was present, the evidence was deemed to be either insufficient or conflicting. There was no systematic report on the frequency of complications.

The appropriateness of chiropractic spinal adjustment/manipulation was assessed by two expert panels, one multidisciplinary and one all chiropractic, each rating a comprehensive array of over 1500 clinical scenarios for appropriateness or inappropriateness of chiropractic intervention. These scenarios varied according to length of symptoms; clinical course of pain; presence of co-morbid diseases; history in response to previous treatments for back pain; findings on physical examination; and findings on lumbosacral radiographs, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Among the appropriate conditions recognized by the multidisciplinary panel53 for chiropractic intervention were acute (less than 3 weeks’ duration) back pain with the absence of neurologic findings and acute back pain with minor neurologic findings and uncomplicated lumbosacral neurologic radiographs. In the final ratings, panelists rated 7% of all conditions as appropriate for spinal adjustment/manipulation, although these conditions represent the majority of back pain patients. As might be anticipated, the all-chiropractic panel54 rated a higher percentage (27%) of all conditions as appropriate. Inappropriate ratings by the multidisciplinary and all-chiropractic panels were 60% and 48%, respectively. On the all-chiropractic panel, there was a higher level of intrapanel agreement than was achieved on the multidisciplinary panel (63% versus 36%).

Depending upon the criteria for assessment, the RAND field studies have reported varying levels of appropriateness of chiropractic intervention. For one site (San Diego), the level of appropriateness varied between 38% and 74%; the level of inappropriateness ranged from 19% and 7%, depending upon whether the criteria of the multidisciplinary or the all-chiropractic panel were applied. Data from other geographic areas of the United States is required before inferences for the national population can be drawn; it has been demonstrated that such a study is feasible. 55

Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Trial Ratings for Low Back Pain

In an effort to filter out low-quality studies, systems rating trial quality have abounded as an attempt to ensure the legitimacy of the evidence used to support various therapeutic approaches. These ratings form the cornerstone of both systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses. Systematic review is defined as a comprehensive and rigorous review of the peer-reviewed scientific literature requiring a predetermined threshold of graded quality in order to be included. In meta-analyses, on the other hand, actual effect sizes are calculated from pooled results of different clinical trials using a variety of statistical procedures, taking into account the size of each study.

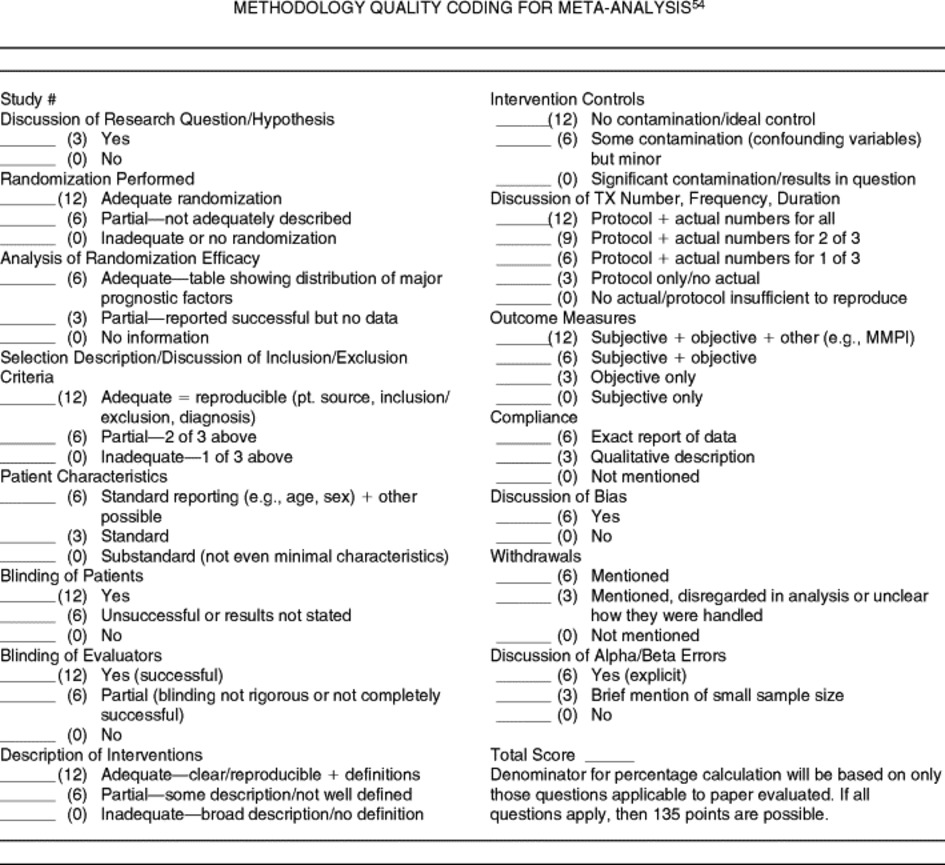

An excellent example of a rating system for trial quality is the scoring mechanism shown in Fig. 23-2, taken from an earlier meta-analysis addressed to the concept of spinal manipulative therapy in the treatment of low back pain. In Anderson’s study of 23 RCTs, in most cases spinal manipulative therapy was compared with other therapies rather than true no-treatment placebos. Although the effectiveness of spinal adjustments per se could not be clearly evaluated, they consistently proved more effective in the treatment of low back pain than any of the comparative interventions. 56

|

| Fig. 23-2 Methodology quality coding for meta-analysis. (From Shekelle PG et al: The appropriateness of spinal manipulation for low back pain: indications and ratings by an all-chiropractic expert panel, monograph no R-4025/3-CCR/FCER, Santa Monica, 1992, RAND.) |

Shekelle’s meta-analysis, noteworthy in that it represented the first time a chiropractor (Alan Adams) coauthored an article in the Annals of Internal Medicine, retrieved 58 articles representing 25 trials. The authors concluded that the data supported the short-term benefit of spinal manipulation in some patients, particularly those with uncomplicated, acute low back pain. Data regarding chronic low back pain at the time of this publication were judged insufficient to evaluate the efficacy of spinal manipulation in managing this particular condition. 25

This qualification may no longer stand. The evidence supporting the use of spinal adjust ment/manipulation in managing chronic low back pain is now substantial. In a systematic review of 16 randomized controlled trials involving manipulation and adjustment for chronic low back pain, van Tulder and colleagues identified two of high-quality, only one of which was judged to be of sufficient quality by Bronfort and shown in Table 23-3. 31,57 Here, the evidence supporting manipulation for chronic low back pain is found to be actually stronger than that for acute conditions. There is limited evidence that manipulation is more effective than a placebo treatment for acute low back pain (level 3).

| Scale | No of Items | Randomization | Blinding | Withdrawals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrew, 1984 | 11 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 |

| Beekerman et al, 1992 | 24 | 4.0 | 12.0 | 16.0 |

| Brown, 1991 | 6 | 14.3 | 4.8 | 0.0 |

| Chalmers et al, 1990 | 3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 |

| Chalmers et al, 1981 | 30 | 13.0 | 26.0 | 7.0 |

| Cho, Bero, 1994 | 24 | 14.3 | 8.2 | 8.2 |

| Colditz et al, 1989 | 7 | 28.6 | 0.0 | 14.3 |

| Deltsky et al, 1992 | 14 | 20.0 | 6.7 | 0.0 |

| Evans, Pollack, 1995 | 33 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 11.0 |

| Goodman et al, 1994 | 34 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 5.9 |

| Gotzsche, 1989 | 16 | 6.3 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| Imperiale/McCullough, 1990 | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Jadad et al, 1996 | 3 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 20.0 |

| Jonas et al, 1993 | 18 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 5.6 |

| Kjeijnen et al, 1991 | 7 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 |

| Koes et al, 1991 | 17 | 4.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 |

| Levine, 1991 | 29 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Linde et al, 1997 | 7 | 28.6 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Nurmohamen et al, 1992 | 8 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| Onghena/van Houdenhove, 1992 | 10 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 2.9 |

| Poynard, 1988 | 14 | 7.7 | 23.1 | 15.4 |

| Reisch et al, 1989 | 34 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 2.9 |

| Smith et al, 1992 | 8 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 12.5 |

| Spitzer et al, 1990 | 32 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 9.4 |

| ter Riet, 1990 | 18 | 12.0 | 15.0 | 5.0 |

There is no evidence that manipulation is more effective than [other] physiotherapeutic applications…or drug therapy…. There is strong evidence that manipulation is more effective than a placebo treatment for chronic LBP [low back pain] (level 1). There is moderate evidence that manipulation is more effective for chronic LBP than usual care by the general practitioner, bed-rest, analgesics, and massage (level 2). *58

*In the van Tulder review, Level 1 refers to “strong” evidence, with multiple, relevant, high-quality RCTs; Level 2 refers to “moderate” evidence, with one relevant, high-quality RCT and one (or more) relevant, low-quality RCT; and Level 3 refers to “limited” evidence, with one relevant, high-quality RCT or multiple relevant, low-quality RCTs.

A somewhat different interpretation was reached in Bronfort’s systematic review. 26 Here, the evidence supporting spinal adjustment/manipulation for managing either acute or chronic low back pain was judged to be “moderate,” whereas the evidence supporting spinal adjustment/manipulation for managing a mix of chronic and acute low back pain was considered “inconclusive.” Furthermore, all but one of the back pain studies considered to be of sufficient validity were eliminated by the criteria invoked by van Tulder, whereas the latter study included one trial58 that had been rejected by Bronfort.

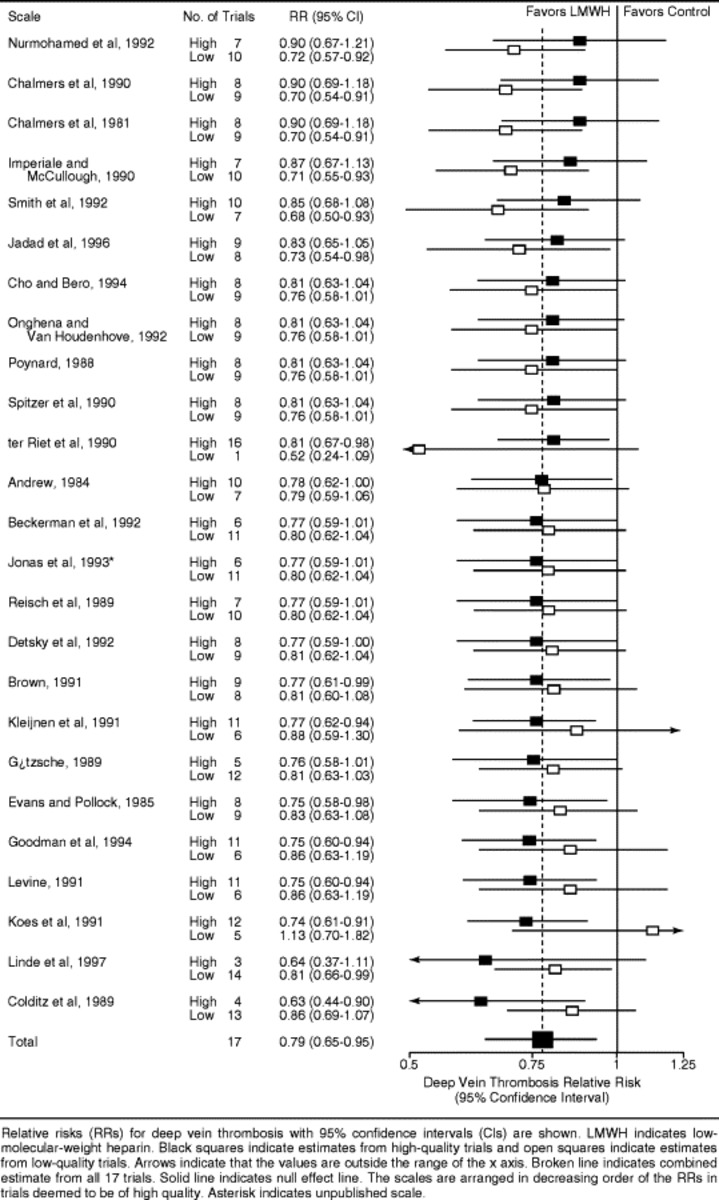

The fact that systematic reviews may conflict in both their conclusions and their acceptance of particular studies is troublesome. A recent study dramatically illustrates how meta-analyses can be reduced to subjective value scales, with disastrous results. In their efforts to compare two different preparations of heparin for their respective abilities to prevent postoperative thrombosis, Juni and colleagues demonstrated that diametrically opposed results could be obtained in different meta-analyses, depending upon which of 25 scales is used to distinguish between high- and low-quality RCTs. The root of the problem is evident from the variability of weights given to three prominent features of RCTs (randomization, blinding, and withdrawals) shown in Table 23-3 by the 25 studies that have compared the two therapeutic agents. In one study (Jadad et al, 1996), one third of the total weighting of the quality of the trial is afforded to both randomization and blinding, whereas in another (Imperiale and McCullogh, 1990), none of the quality scoring is derived from these two features.

Widely skewed intermediate values for the three aspects of RCTs under discussion are apparent from the 23 other scales presented. The astute reader will immediately suspect that sharply conflicting conclusions might be drawn from these different studies—and these are amply borne out by the statistical plots shown in Fig. 23-3. Here each of the meta-analyses listed resolve the 17 studies they have reviewed into high- and low-quality strata, based upon their respective scoring systems. It can be seen that 10 of the authors selected scored a statistically superior effect of one heparin preparation (i.e., the low-molecular–weight heparin [LMWH]) over the other (but only for the low-quality studies). Seven other studies reveal precisely the opposite effect, in which the high– but not the low-quality studies display a statistically significant superiority of LMWH.

|

| Fig. 23-3 Results from sensitivity analyses of studies on heperin, dividing trials in high- and low-quality strata, using 25 different quality assessment scales. Note the wide range in conclusions about the value of the medication being studied. LMWH, Low molecular weight heparin. (From Juni P et al: The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis, JAMA 282(11): 1054, 1999.) |

Therefore depending upon which scale is used, the clinician can either demonstrate or refute the clinical superiority of one clinical treatment over the other. In this manner, all the rigor and labor-intensive elements of the RCT and its interpretation by the meta-analysis are simply reduced to subjective value judgment through the arbitrary assignment of numbers in the weighting of experimental quality. 59

Returning to the discussion on low back pain, yet another systematic review of RCTs cites adequate follow-up periods, avoidance of cointerventions (i.e., additional therapies used with adjustment/manipulation), and avoidance of dropouts as frequent strengths. Recurrent weaknesses, however, include randomization procedures, sample sizes, and blinded assessments of outcomes (the latter being virtually impossible to perform in a trial involving manual therapy, because the physical nature of adjustment/manipulation is so difficult to disguise). 60 Moreover, a meta-analysis of 51 literature reviews of spinal manipulative therapy suggests that, although the overall methodologic quality was low, 9 of the 10 methodologically best reviews reached positive conclusions regarding spinal adjustments. 61

One key point bears repeating: The results of systematic reviews and meta-analyses are completely dependent on the criteria chosen by the authors of the reviews. Consumers of such literature are therefore well advised to read the text, not just the conclusions in the abstract, to understand and properly evaluate the validity of a study’s conclusions.

Lumbar Disk Herniation Research

The options for treating disk herniations are surgery or conservative care, the latter often involving spinal adjustment/manipulation. With no controlled trials to date that directly compare these two options, it is perhaps helpful to mention that, during a 30-year career, one leading orthopedic surgeon never encountered a patient with a disk herniation that was aggravated by manipulation. 62

Two randomized trials currently support the wisdom of considering spinal adjustment/manipulation as a treatment option for this condition. One study (involving 51 cases of myelographically confirmed disk herniation) compared rotational mobilization with conventional physical therapy (e.g., diathermy, exercise, postural education). The manual therapy group demonstrated greater improvement in range of motion and straight leg raising compared with the physical therapy cohort, leading Nwuga to conclude that manipulation was superior to conventional treatment. 63

The second trial examined 40 patients with unremitting sciatica as the result of lumbar disk herniation with no clinical indication for surgical intervention. Subjects were randomized into two treatments: (1) chemonucleolysis (i.e., chymopapain injection under general anesthesia) and (2) adjustment/manipulation (i.e., 15-minute treatments over 12 weeks, including soft tissue stretching, low-amplitude passive maneuvers of the lumbar spine, and the judicious use of side-posture adjustments/manipulations). Back pain and disability were appreciably lower in the manipulated group at 2 and 6 weeks, with no improvement or deterioration in the chemonucleolytic group. By 12 months there were improvements in both groups with a tendency toward superiority in the manipulated cohort. Costs of treatment in the adjustment/manipulation group were less than 30% encountered by the injected patients; furthermore, the latter group averaged expenditures of 300 British pounds for treatment failures with no such costs experienced by the manipulated population. 64

Further support for adjustment/manipulation in the treatment of disk herniations is provided from several prospective studies.65666768 and 69 The largest involved 517 patients diagnosed with lumbar disk protrusion, 77% of these having a favorable response from pain after manipulative/adjustive therapy. 68 A literature review from Cassidy70 suggests that an additional 14 of 15 patients with lumbar disk herniations experienced significant relief from pain and clinical improvement after a 2- to 3-week course of side-posture adjustment/manipulation.

Cassidy, 70 who disputes the assertion by Farfan that rotational stress causes disk failure, supports the safety of rotational adjustment/manipulation in the treatment of lumbar disk herniations. Farfan’s work demonstrates that, in rotation, normal discs withstand an average of 23 degrees and degenerated discs an average of 14 degrees before failure. 71 However, posterior facet joints limit rotation to only 2 to 3 degrees. Facet fracture would therefore be necessary before further rotation could occur, 72 and any disk failures produced experimentally by torsion would be caused by peripheral tears in the annulus, rather than prolapse or herniation. 72

NECK PAIN RESEARCH

The RAND Appropriateness Study: Manipulation and Mobilization of the Cervical Spine

As it had for the low back pain study, the RAND Corporation conducted both a literature review and a multidisciplinary panel appropriateness study for cervical spine, headache, and upper-extremity disorders. With regard to the cervical spine, the RAND literature review suggested that short-term pain relief and enhancement of the range of motion might be accomplished by manipulation or mobilization in the treatment of subacute or chronic neck pain; literature describing acute neck pain was regarded as extremely scanty73 and remains so.

For subacute and chronic neck pain, the trial receiving the highest rating indicated that, for neck and back complaints together, improvements in severity of the main complaint were larger with manipulative therapy rather than physiotherapy. For neck complaints only, the mean improvement in the main complaint as shown by the visual analog scale (where patients rate the level of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10) was slightly better for manipulative rather than physical therapy. 74 Cassidy’s trial, studying 100 subjects with unilateral neck pain with referral into the trapezius, revealed that immediately after the intervention, 85% of the manipulated group and 69% of the mobilized group reported pain improvement. The decrease in pain intensity was more than 1.5 times greater in the manipulated group. 75 The literature regarding upper extremi ties, headache, and complications is referred to in the following appropriate sections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree