Sports chiropractic and sports medicine have grown and matured over the years. Sports medicine has its origins in the Roman Empire, when treatment was provided to help gladiators become ready for competition. In the last century, sports medicine has progressed from a hobby of some in the medical profession who dabbled in treating athletes to its current status as an area of specialization with fellowship-based training programs. A variety of professionals and paraprofessionals specialize in the care of athletes, including practitioners of medical primary care specialties (e.g., internal medicine, family practice, pediatrics, gynecology), secondary care specialties (e.g., orthopedics, neurology, endocrinology), and limited licensed professions (e.g., chiropractic, dentistry, optometry, podiatry, psychology). Certain paraprofessionals are also involved in sports medicine (e.g., athletic trainers, personal trainers, nutritionists, physical therapists). Finally, some in the research community consult with and conduct research on athletes (e.g., exercise physiologists, biomechanists).

Sports and sports medicine establishments resisted sports chiropractic for many years, and progress has been gradual. However, as more and more athletes benefited from chiropractic care, they continued to seek out chiropractic care on their own and then demanded the inclusion of chiropractors on sports medicine teams. Despite much initial and some continued resistance, team athletic trainers and medical physicians gradually began to refer players to chiropractors. Eventually, many teams included chiropractors in official capacities on their sports medicine teams. 1 Currently, sports chiropractors are members of any comprehensive sports medicine staff, from the Olympics and professional sports to collegiate, scholastic, and youth club sports.

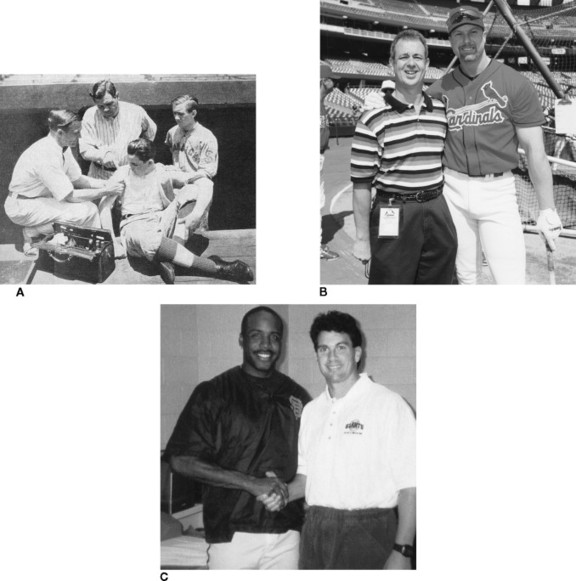

Babe Ruth relied heavily on the treatment he received from Erle “Doc” Painter, a chiropractor who served as athletic trainer for the New York Yankees2,3 (Fig. 19-1). The U.S. Olympic sports medicine team first included a chiropractor, George Goodheart, at the Lake Placid Winter Olympics of 1980. Eileen Haworth was the first U.S. Olympic team chiropractor to participate in the physician-training program at the U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) Colorado Springs training center in 1982. Currently, Doctors of Chiropractic (DCs) seeking to participate in the U.S. Olympic program apply for internships at the training center where they are evaluated for the breadth and depth of their clinical competence and for their ability to work cooperatively within a multidisciplinary team. 4

|

| Fig. 19-1 Home run record breakers Babe Ruth (A), Mark McGwire (B), and Barry Bonds (C) with their respective chiropractors, Erle “Doc” Painter, Ralph Filson, and Nick Athens. (A courtesy NCA’s Chiropractic Journal, May 1934; B courtesy American Chiropractic Association; C courtesy Today’s Chiropractic.) |

Organizationally, sports chiropractic in the United States received a major boost when Robert Hazel, Jr., was elected President of the Council on Sports Injuries and Physical Fitness (Sports Council) of the American Chiropractic Association (ACA). Under his leadership the Council’s membership increased substantially, and the organization developed an indexed, peer-reviewed scientific publication, Chiropractic Sports Medicine, later renamed the Journal of Sports Chiropractic and Rehabilitation. * Relationships were established with various sports organizations, including the NFL Players Association and Pro Beach Volleyball, to provide credentialed chiropractors for sporting events or to receive referrals for the care of athletes.

*Journal of Sports Chiropractic and Rehabilitation ceased publication in 2001.

The ACA Sports Council also worked to develop postgraduate board certification, with programs for Certified Chiropractic Sports Physicians (CCSP) and Diplomate of the American Chiropractic Board of Sports Physicians (DACBSP), both regulated by the American Chiropractic Board of Sports Physicians (ACBSP). † The ACBSP has worked diligently to establish high standards for competency and ethics. 5

†Both designations replace the term physician with practitioner for those practicing in states that deny chiropractors the use of the term physician.

SPORTS INJURIES IN CHIROPRACTIC PRACTICE

In many ways, sports chiropractic differs little from general chiropractic practice. Many of the conditions treated are observed in the general population, although with different causes. Examples include (1) an ankle sprain from stepping on a toy that a child left in the hallway, rather than from landing on another player’s foot when rebounding in basketball; (2) hurting the lower back from picking up a box at work, rather than from lifting a heavy weight in the gym; or (3) lateral epicondylosis from the excessive use of a screwdriver, rather than from playing tennis.

Unique Elements

Many unique elements exist in the management of the athletic patients. Dietary education is more often furnished with the intent of improving athletic performance rather than treating obesity. Added emphasis on soft tissue techniques and extremity adjustment/manipulation also is provided, because injuries to soft tissues and extremities are the most common type of sports injuries. Many athletes seek chiropractic care in an effort to find a performance advantage—an ergogenic effect (i.e., an effect that tends to improve or enhance athletic performance). Two studies6,7 investigated the ergogenic effects of chiropractic care; however, because of methodologic problems, any conclusions as to possible benefits are premature.

An understanding of the unique psychology of the athlete is important. In general practice, the chiropractor must be vigilant for patients with fear avoidance behavior who need motivation to work through the pain and effort of rehabilitation to treat their conditions. 8,9 In sports chiropractic practice, on the other hand, the practitioner must be vigilant for the athlete whose motivation to return to training or competition causes him or her to work too hard on rehabilitation or to return to a high level of activity too soon. In fact, the athlete’s motivation to continue to train and compete may be the source of many injuries. 10

Although injured workers often want their DCs to provide an excuse from work, injured athletes are fearful that the doctor will tell them to refrain from training or competition. Instructing the injured athlete to discontinue training (or competition) often leads the athlete to discontinue care instead of discontinuing training. Therefore whenever prudent, practitioners should tell athletes to reduce training volume (duration times intensity) and to discontinue training only if their condition does not improve at an acceptable rate. This approach often results in the athlete taking responsibility for the decision to discontinue training rather than blaming the doctor for “making” him or her stop.

Sports Medicine Team

Chiropractors seeking to integrate within a multidisciplinary sports medicine team must understand the roles of all the members on that team, particularly the leadership role of the athletic trainer. The team’s goals are preventing, treating, and rehabilitating sports injuries, as well as working to enhance the performance of the healthy athlete.

ON-FIELD EVENT PARTICIPATION

On-field event participation can be one of the most satisfying venues for sports chiropractors. There is, of course, the excitement of being at an athletic event, often with access to locations not ordinarily open to nonplayers. Watching a football game from the sidelines, a hockey game from the bench, or a marathon from the finish line provides an unequaled perspective on the sport. Depending on the event, this type of participation may be contractually paid by the team, or more often this participation occurs on a voluntary basis as a member of an event’s sports medicine staff. Such work can be rewarding both from an experiential standpoint and from a marketing standpoint. However, care should be taken to avoid overstepping the bounds of the relationship. Sometimes the benefit will be to the profession and not the individual professional, particularly when working at national and international class events. In such cases, the athletes are usually not from the locale where the event is taking place and thus will not become the chiropractor’s regular patients. There is value, nonetheless, as the athletes discover that chiropractic care should become part of their sports health care.

As mentioned earlier, the hierarchy of the sports medicine staff needs to be understood at the outset. Once that understanding is established, the sports chiropractor at an event has the opportunity to learn from other professionals and possibly teach them about chiropractic. Further, treating an athlete who needs to continue competing at an event is a great test of the practitioner’s clinical skills. It is similar to the advertisement for automobile tires in which there are images of race cars and an announcer who says that they learn more in a day at the track about how to make tires better than they would in years of testing on the road. Similarly, the skills the practitioner learns while helping injured athletes to compete also helps improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the treatment of nonathletes. Treatment at events runs the gamut from old to new injuries to helping improve the athletes’ neuromusculoskeletal function so that they may compete at a higher level.

MECHANISMS OF SPORTS INJURIES

Seven basic mechanisms of sports injuries have been characterized and may occur singularly or in combinations. They are the following:

• Contact (e.g., tackle in football)

• Impact (e.g., hitting the ground while running)

• Overuse (e.g., impingement syndrome from swimming)

• Dynamic overload (e.g., muscle strain from excessive effort)

• Inflexibility and muscle imbalance (e.g., hamstring muscle strain from tightness and weakness of the hamstrings)

• Structural vulnerability (e.g., hyperpronation of the foot or joint dysfunction)

• Rapid growth (e.g., Osgood-Schlatter disease) 11

The degree of injury from any of these mechanisms will vary, depending on the force involved. Injuries range from the macro level (i.e., evident or acute onset injury, including Grade II and III sprains and strains, fractures) to the micro level (i.e., repetitive or overuse injuries including tendinosis, myofascial trigger points, Grade I sprains and strains, stress fractures, stress reactions). Obviously, macrotrauma more likely involves high magnitude forces. Such forces are typically associated with high-velocity sports such as skiing or those involving more massive athletes, such as football. 12 Microtrauma is common to all sports, making up to 50% of all injuries. 11 Typically called overuse injuries, these are the result of repetitive low-magnitude forces, causing microscopic disruption of the structure of the involved tissues. 12

High-force injuries cause failure or rupture of the tissue to various degrees. Thus depending on the force and the rate of application of that force, when muscle, ligament, and tendon are subjected to high loads, they will tear at a microscopic level (Grade I), tear at the macroscopic level resulting in partial tear (Grade II), or suffer a complete tear (Grade III). 11

High rates of speed or a great magnitude of load can cause bone to fracture. Repeated low-force loading may result in a stress reaction (evident on a bone scan but not on radiographic films) or a stress fracture (evident on both bone scan and in radiographic studies). 13,14 The specific tissue injured depends on the rate of loading and the age of the athlete. Younger athletes are more prone to avulsion fractures, whereas the same mechanism of injury in the older athlete will spare the bone and injure the ligament, muscle, or the tendon. 11

Neuromusculoskeletal Dysfunction

A variety of neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) conditions affecting athletes may be classified as dysfunction. The primary NMS dysfunction treated by chiropractors is the subluxation complex. 16 This dysfunction includes but is not limited to spinal and extremity joint dysfunction (i.e., subluxation), myofascial trigger points (i.e., tender, neurologically hyperactive loci in muscle that can produce referred pain), 17 and adhesions (i.e., scar tissue). 18,19 These are common sequelae to training and competing.

Prevention of Sports Injuries

Understanding the rules, techniques, biomechanics and mechanisms of injuries in each sport is crucial to preventing injuries and is the minimal knowledge needed to work with athletes in any sport. Although a detailed description of injuries specific to each sport is beyond the scope of this

Microtrauma is typically the result of repetitive use, the so-called overuse syndrome. Overuse syndromes are believed to result from repeated microtrauma that overrides the body’s ability to repair the injury, which may be considered analogous to fatigue failure of mechanical parts. Overuse syndromes affect athletes in all sports. 12

Classifying these microtraumatic conditions as overuse syndromes is hazardous; if they are due to overuse, then the only treatment would be to use the injured part less. Thus it might be preferable to think of these conditions as “mal-use” syndromes. Dysfunction (both joint and muscle), improper equipment, improper sports technique, and increasing the volume of training (intensity and duration) too rapidly are all causes of overuse syndromes.

Common examples include the following:

Tendinosis. Although formerly called tendinitis, this appellation appears to be inappropriate. Rather than being an inflammatory condition, biopsies have shown a degeneration of a tendon.

Stress fracture. This microfracture in bone can be observed on both radiographic films and bone scans.

Stress reaction. The same condition as a stress fracture but at an earlier stage, this microfracture can only be found on bone scans.

Shoulder impingement syndrome. Also known as swimmer’s shoulder, the greater tuberosity of the humerus impinges on the supraspinatus tendon and subacromial bursa, resulting in pain and tendon degeneration.

Patellofemoral arthralgia. In this condition also known as runner’s knee, the patellofemoral joint becomes irritated, which is often the result of tight hamstring muscles, hyperpronation, or improper choice of running shoes.

Iliotibial friction syndrome. In this common injury in runners, a tight tensor fascia lata causes the iliotibial band to snap over the lateral femoral epicondyle.

text, an outstanding discussion of sport-specific mechanisms of sports injuries can be found in Sports Injuries: Mechanisms, Prevention, and Treatment. 20 For the chiropractor in particular, differentiating macrotrauma and NMS dysfunction is important.

Preventing macrotrauma may not be possible, because these injuries are often accidental. Increased awareness of the terrain, the movements and location of other competitors, improved training, better protective equipment, and safety-based improvements in sports rules may all decrease (although never eliminate) the incidence of macrotrauma. Microtrauma may be avoided by improved training, better techniques, and improvements in equipment, ensuring that the intensity and duration of training does not exceed the body’s ability to adapt to the demands of training.

Because dysfunction is associated with microtrauma, its prevention is dependent on preventing microtrauma. Similarly, it is reasonable to assume that correcting such dysfunction should help prevent other sports injuries by improving NMS function. Minimizing biomechanical dysfunction through spinal and extravertebral adjustment/manipulation, as well as other adjuncts, is a central focus of the sports chiropractor.

BIOMECHANICS, PHYSIOLOGY, AND REPAIR OF SPORTS INJURIES

Kinetics, Kinematics, and Kinesiology

A complete understanding of the nature of the injury (i.e., what tissue is injured and the extent of the injury) requires understanding the biomechanics of injury. The biomechanical principles relevant to sports injuries are the kinetics (forces), kinematics (movements), and kinesiology (muscles causing the forces and movements) of the injury process and the material properties of the hard and soft connective tissues involved. 21 Knowing which tissues receive or generate forces during a certain movement enables the practitioner to locate the weak link in the kinetic chain.

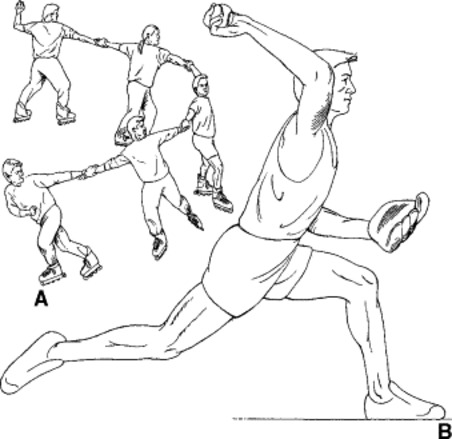

The kinetic chain is the sequence of links (bones) that transmit forces (kinetics) generated by muscles (kinesiology) to create movement (kinematics). For any action, a specific sequence of the links in the kinetic chain allows for the efficient generation of forces, which causes the movement required for that activity. Problems in the sequence result in injuries somewhere along the kinetic chain. 22 Examples of the kinetic chain can be seen in Fig. 19-2. Each skater is considered a link in the chain. The forces generated by the whole chain of links (skaters) are summated, and the result is that the last person in the chain is moving faster than the first. However, a problem anywhere along this chain (dysfunction of a link) will affect the function of the “whip” (see Fig. 19-2, A).

|

| Fig. 19-2 Examples of kinetic chains. A, A chain of roller skaters executing a whip maneuver. B, The body segments of a baseball pitcher. (From Zachazewski JE, Magee DJ, Quillen WS: Athletic injuries and rehabilitation, Philadelphia, 1996, WB Saunders.) |

Steindler23 coined the terms closed kinetic chain and open kinetic chain. A closed kinetic chain is one in which the terminal joint of the limb that is moving is fixed to an immobile object. The classic example is running. The foot is the terminal joint, and it is on the immobile object—the ground. Forces that are generated in the leg push against the ground, causing movement. The classic example of an open kinetic chain activity is throwing a ball (see Fig. 19-2, B). where the arm functions as an open kinetic chain, whereas the leg functions as a closed kinetic chain.

In a baseball pitcher (see Fig. 19-2, B), an alteration in the function of any joint from the great toe all the way to the fingers of the hand will have an effect on some other link that affects the pitch. The classic example is what has become known as the “Dizzy Dean syndrome.” Dizzy Dean, a Hall of Fame baseball pitcher, fractured his left big toe in the 1937 All-Star game. Dean returned to play too rapidly, before the toe completely healed. He altered his throwing mechanics to lessen the pain in his toe, resulting in a career-ending injury to his pitching shoulder. 21 Thus the pitcher with shoulder pain requires an examination of not only the shoulder but also all the links in the kinetic chain for the throwing motion. The practitioner must determine whether a problem in another link has caused the athlete to change throwing mechanics and, consequently, produced the shoulder problem. Even when the injury is the result of trauma, the practitioner should examine the links in the kinetic chain. Even a minimally malfunctioning link may be of the magnitude that could prevent complete recovery, despite being below the threshold necessary to cause a direct injury.

Equating pain with inflammation is a common misconception about the pathophysiology of tendon injuries (tendinopathies) (Fig 19-3). This erroneous belief has led to the misnaming and consequent improper treatment of tendinopathy. Typically, this condition has been called tendinitis; however, because of the relatively avascular nature of tendons, most tendinopathy is degenerative rather than inflammatory, 11 which led Puddu and colleagues to coin the currently preferred term, tendinosis, in 1976. 24

|

| Fig. 19-3 Derek Parra, 2002 Olympic Gold Medalist in speed skating, with his chiropractor, Keith Overland. (Courtesy Keith Overland.) |

Role of Inflammation in Repair

It is essential to understand the repair process. Typically, health care providers treating trauma try to minimize the inflammatory response. However, inflammation is a crucial, natural step in the repair of any injury. Although a feature of such diseases as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammation that is out of control or “purposeless” is not typical of sports injuries. 11 The current trend of treating rheumatoid arthritis with antiinflammatory medications appears to have affected the methods used to treat all injuries that start with inflammation. A commonplace assumption is that inflammation is harmful and should always be stopped. When treating injuries after the acute stage, it is important to remember that the presence of pain does not necessarily mean that inflammation is also present. Pain is only one of the four cardinal signs of inflammation; the others are swelling, redness, and heat.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree