Cochrane Collaboration

Disk Bulge

Endplate

Secondary Prevention

Chiropractic has always emphasized manual treatment of the locomotor (neuromusculoskeletal) system—particularly the spinal column—in its approach to health care. The emphasis on the spinal column is based on the tenet that the nervous system controls healing and that normalization of the function of the vertebral column joints will have a positive effect on health of the entire organism.

Because of chiropractors’ success in managing lower back pain (LBP), the profession has gained increased legitimacy for treating a variety of spinal disorders (e.g., headache, whiplash syndrome, sciatica). Chiropractors with expertise in sports and orthopedics have also gained credibility for their skill in managing musculoskeletal problems involving the extremities. Chiropractic management of somatovisceral disorders affecting the cardiovascular (e.g., high blood pressure), respiratory (e.g., asthma), digestive (e.g., ulcers), and other systems of the body has not attained this degree of credibility. As a result, the vast majority of patient visits to chiropractors are for musculoskeletal problems, with LBP ranking as the number one reason for a patient to visit a doctor of chiropractic. 1

LBP has a generally positive natural history but can be a very complex disorder. LBP is estimated to be at least a $30-billion problem in the United States. 2 The traditional view of back problems was that they represent primarily acute, self-limiting conditions that resolve within 4 to 6 weeks. 3 However, recent epidemiologic studies contradict this rather optimistic picture. Back problems are now recognized as chronic ailments that are characterized with frequent acute spikes. 4 Although back pain is rarely disabling, 5 the minority of cases that involve disability account for a disproportionate percentage of the overall health care costs. 6

A great deal of evidence now exists regarding appropriate treatment for many spinal disorders, and international guidelines have flourished since 1986.789 and 10 Waddell has stated that the most cost-effective approach to managing this problem is to pursue secondary prevention efforts more aggressively on subacute patients before chronic disability is fully established. 11 (Primary prevention is the prevention of a disorder before it has begun; secondary prevention efforts seek to keep a subacute disorder from becoming chronic.)

In particular, the major patient management errors have involved the traditional emphasis on a biomedical rather than a biopsychosocial approach. The biomedical approach has too often included labeling patients as damaged (arthritis) or injured (ruptured disk), overpre scribing bed rest, recommending early imaging, and selecting surgical candidates inappropriately. 12 In contrast, the biopsychosocial model emphasizes early reassurance (unambiguous explanation that the patient’s back pain is not the result of serious disease processes and has an overall good prognosis) and reactivation (advice that recovery is accelerated by gradual resumption of activities) along with spinal adjustment/manipulation and exercise. 11,13,14

The biomedical approach leads to the cascade effect in the clinical management of patients with back pain. The downward spiral begins when high-tech imaging replaces a thorough history and examination. Medicalization of back pain results from an underestimation of the iatrogenic (harmful) effects of overly aggressive diagnosis (imaging) and treatment (surgery). 15 In addition, the psychologic consequences of labeling patients with pain resulting from coincidental structural pathologies are commonly ignored. 12

When a patient feels persistent pain, this reinforces negative attitudes about the relationship of activity and pain as the patient takes on the “sick” role. 16 The result is activity avoidance and further deconditioning of the involved portions of the musculoskeletal system. Unfortunately, reconditioning time is longer than deconditioning time. 17 Therefore reactivating patients as early as possible is important. Numerous studies have shown that gradually resuming activities is both safe and effective for acute, subacute, and chronic back pain.7891819 and 20

Chiropractors are ideally suited to play a leading role in managing neuromusculoskeletal disorders. LBP is an excellent proving ground for the profession. However, if chiropractors are to benchmark themselves as experts, then they must gain greater knowledge and skill in the area of rehabilitation and exercise. Generally referred to as active care, this approach encourages patients to participate actively in the resolution of their conditions rather than waiting for clinicians to “fix” them. The ancient role of the physician as helper or teacher must accompany the contemporary medical emphasis that defines the doctor’s role in terms of curing or fixing.

SCIENTIFIC PRINCIPLES

Diagnosing Back Pain: Current Evidence and Deficiencies

Appropriate management of any condition depends on accurate diagnosis of the patient. Treatment should be guided by classification of patients into discrete groups that have unique characteristics amenable to specific interventions. Unfortunately, most consensus guidelines suggest that less than 20% of patients with back pain can be given a clear structural diagnosis of their condition. 7 Fortunately, new evidence indicates the promising role of determining the patient’s functional diagnosis,21 which consists of identifying the relevant physical performance deficits (e.g., strength, endurance, mobility, balance, coordination).

Meta-analysis of the scientific literature on diagnosis of back pain reveals various labels being used without appreciable evidence of validity. 22 International consensus guidelines agree that back pain can be classified in three groups: (1) those with red flags, such as tumor, infection, fracture, and serious medical diseases (less that 2%); (2) those with nerve root compression (less than 10%); and (3) nonspecific back pain (85% to 90%). Most research on the effectiveness of different interventions has assumed that the nonspecific back pain is a homogenous group. 22 However, to categorize most back pain in this generic fashion may cause researchers and practitioners to lose sight of potentially significant distinctions in this broad category. LaBoeuf-Yde explains that specific interventions, which may be beneficial for a certain subgroup, may not have demonstrable clinical effectiveness if given to a heterogeneous population. 23 Thus many hopeful methods will be erroneously assumed to be ineffective. Future research should therefore strive to determine if the nonspecific classification actually represents a homogeneous or heterogeneous population.

Erhard and Delitto have shown that subclassification of the nonspecific group is possible with reliable tests. 24 Treatment that is then matched to the appropriate subclassification has been shown to be superior to unmatched treatments. 24 Furthermore, a treatment that is driven by subclassification has been shown to be superior to the generic treatment recommended by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) for the broad nonspecific category. 25 Researchers at Washington University have similarly validated a subclassification scheme based on functional evaluation of movement patterns. 26,27

Although ordering advanced imaging tests to find the cause of pain is tempting, structural pathologic conditions are quite common and usually coincidental. Disk bulges, facet joint degeneration, endplate changes, and mild spondylolisthesis all correlate more with age than they will with symptoms. Exceptions include disk extrusions, moderate or severe canal stenosis, and nerve root compression. 28

Although recent literature points out past errors, unanswered questions remain. The fundamental problem in dealing with back pain continues to be identifying which patients will respond best to which interventions. For instance, which patients respond best to adjustment/manipulation, to reassuring counsel, to exercise, to medication, and to various combinations? General guidelines adhering to a biopsychosocial model have emerged and suggest a new path.

Psychosocial and Performance Factors

The inherent difficulty in diagnosing LBP has led to great frustration for both patients and clinicians. Given that most back problems are not the result of structural pathologic abnormalities (arthritis, herniated disk) or serious disease (tumor, infection, fracture), and because the majority of patients benefit from prompt reassurance and early reactivation advice, a primary goal of care should be to reassure patients about the benign nature of their pain and the safety and value of resuming normal activities. Thus prevention of deconditioning—both physical and psychologic—is a fundamental goal of the modern management of spinal disorders.

Deconditioning is the diminished ability to perform tasks involved in a person’s usual activities of daily living. The AHCPR LBP guidelines explain that the main goal for treatment of back pain has shifted from treatment of pain to treatment of activity intolerances related to pain. 7 Although a variety of measurements of deconditioning are available, as yet, no “holy grail” has been found (Box 14-1).

Box 14-1

World Health Organization

MEASUREMENTS OF DECONDITIONING

• General functional ability or disability

• Self-report of activity intolerances (e.g., Oswestry form)

• Tests of walking, standing, reaching

• Specific functional deficits or impairments

• Tests of strength, range of motion

From ICDH-2: International classification of functioning and disability, beta-2 draft, full version, Geneva, 1999, World Health Organization.

A patient’s self-report of activity intolerances is a valuable tool in measuring clinical outcomes and even in goal setting. These self-reports are typically questionnaires and, despite being subjective, are excellent outcomes tools because they are highly reliable and responsive. 29 However, the validity of these reports as prescriptive tools is doubtful because they do not correlate well with actual measurements of functional performance ability. 30

Simmonds and colleagues have shown how general functional ability can be measured with simple, reliable, inexpensive, and time-efficient tests. 30,31 Tests such as functional reach, loaded reach, timed up and go, distance walked, and so forth are valuable tools for identifying functional limitations and establishing realistic goals. 32

Clinicians typically make the improvement of specific functions such as range of motion a central goal of care. However, because impairments correlate poorly with pain or disability, they are better used as a means to an end.333435 and 36 Mannion suggests that one half of self-reported disability before treatment and more than one half of it after therapy is unaccounted for by structural, psychologic, voluntary performance, or electromyographic (EMG) fatigue findings. Therefore Mannion believes that new aspects of physical function relating to motor control are worthy of future investigation. 37 These aspects include those involved in nonvoluntary, reflex control of movement, such as position sense, delayed reaction times, and balance tests.3839404142 and 43 McGill has identified that motor control errors can occur as a result of prolonged or repetitive strain or poor aerobic fitness. 44,45

Pain Behavior

Patients’ expectations, motivations, and behaviors influence their performance.464748 and 49 Patient performance can therefore be limited by psychologic and physical factors. Patients who equate hurt with harm develop fear-avoidance behavior, which promotes deconditioning. 50 Pain behavior can also include maneuvers during which the patient repeatedly checks to see if the pain is still present. 51 This behavior can lead to habituation, sensitization, or both. 52 Maras also suggests that personality characteristics associated with increased muscle tension can negatively influence biomechanical performance. 53

A recent study measuring psychologic characteristics related to pain showed improvement using three different active care approaches. 37 No psychologic intervention took place, thus it appears that exercise and activity modification have both psychologic and physical effects. Growing evidence and guidelines suggest that educating patients on the nature and science of back pain is of utmost importance for their recovery. 8,54 Self-help books are available that support the active-care approach and guide the patient through the restorative process. 55,56

Ciccione and Just found that pain expectancies were important not only in chronic patients, but also in acute patients. 57 Thus fear-avoidance beliefs such as pain expectancies begin in acute pain and precede other psychosocial problems that develop as acute pain becomes chronic. In Box 14-2, Vlaeyen and colleagues summarize the impact of fear-avoidance behavior on both general and specific functional abilities. 50

Box 14-2

THE IMPACT OF FEAR-AVOIDANCE BEHAVIOR

PROBLEM:

a. Pain catastrophizing (fearing the worst) is a precursor of pain-related fear.

b. Fearful patients tend to be more hypervigilant (being acutely aware of possible signals of threat).

c. Psychophysical reactivity is present in individuals with fear-avoidance behavior if activities are perceived as harmful, even if they are not actually harmful.

d. Guarded movements such as altered flexion-relaxation ratio are correlated with fear-avoidance beliefs, not actual pain.

e. Anxious patients predict pain earlier during performance of physical tasks such as range-of-motion or straight leg raise tests.

f. Fear and anxiety lead to the tendency to avoid the perceived threat.

g. Pain-related fear leads not only to poor physical performance, but also to restrictions in activities of daily living.

h. Avoidance behavior is highly resistant to treatment because the individual rarely comes into contact with the actual (nonharmful) consequences of the feared situation.

SOLUTION:

a. A cognitive-behavioral approach addresses the individual’s inaccurate predictions about the relationship between specific activities and pain.

b. Education of patients with pain-related fear should emphasize that the fear can be self-managed after repeated desensitization from graded exposures to the feared stimuli.

c. Pain expectancies are corrected with repeated performance of the movements or exercises on subsequent days.

d. After multiple exposures, overpredictions of pain intensity change to match actual pain experience.

From Vlaeyen JWS, Linton S. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain. A state of the art, Pain 85:317, 2000.

Does Evidence of Effectiveness Exist for Active Care in Acute and Chronic Patients?

Acute and Subacute Phase (up to 12 Weeks)

Information and advice emphasizing the value of fitness and the safety of resuming activities achieved superior outcomes to advice that reinforced rest, activity restrictions, and the notion that the spine was injured or damaged (e.g., arthritis, herniated disk). 18 Reassuring workers and encouraging resumption of ordinary activities was superior to medication, bed rest, or mobilization exercises. 20 Early behavior modification through exercise reduced disability 1 year later. 58 An eightfold reduction in the risk of becoming chronic was achieved from information designed to reduce fear and anxiety and provide self-care advice. 59 Little and colleagues recently demonstrated that educational advice that encourages early exercise (not just advice to stay active) or endorsement by a physician of a self-management booklet has been shown to increase patient satisfaction and function while reducing pain. 19

A Cochrane Collaboration systematic analysis on acute LBP concluded that … “there is strong evidence (Level 1) that exercise therapy is not more effective for acute LBP than other active treatments with which it has been compared.”60 Faas and colleagues conducted one notable study that influenced these conclusions, which reported that in the treatment of uncomplicated, acute LBP patients, exercise was no better than usual care from a general practitioner. 61 However, the exercise approach was not individualized to the patients, and a relatively small sample of only three studies were used by the Cochrane Collaboration to reach level-1 conclusions. 62

The Cochrane Collaboration is an international organization formed for the purpose of preparing systematic reviews of the effects of health care interventions.

In most studies of exercise evaluated with meta-analysis techniques, the same exercise type is given randomly to a heterogeneous group of patients with nonspecific LBP. Nonetheless, in clinical practice, most exercise approaches are taught with great emphasis on individualizing the type of exercise to the functional or mechanical attributes of the individual. 24,63 In fact, when a comparison was made between individuals performing exercises that were matched to them versus those that were unmatched, the matched group significantly outperformed the unmatched exercise group. 24 Additionally, a recent paper by the same group describes a study comparing the general exercise recommendations of the AHCPR guidelines to matched treatment based on their subclassification scheme. 25Their conclusion was that specific treatments matched to appropriate patients are superior to a general approach recommended by recent guidelines.

Hides and colleagues have demonstrated that segmental spinal stabilization exercises (SSSE) can prevent multifidus muscle atrophy in subject with acute LBP. 43 SSSE are training maneuvers designed to enhance coordination and endurance of the local, deep muscles that are responsible for segmental control of the spine. Although symptomatic and functional recovery as assessed by Oswestry occurs independent of this intervention, those not receiving the exercises continued to have multifidus muscle atrophy. More recently, Hides and colleagues have demonstrated that such exercises have a secondary preventive effect by reducing recurrences. 42

As with patients experiencing LBP, similar early activation has been found to be effective for neck pain following a whiplash injury.6465 and 66

Because the natural history of low back syndromes reveals that most acute patients recover satisfactorily with minimal intervention, theories suggest that the subacute phase is the ideal time for both active and aggressive treatment. 11,59,67 Hagen and colleagues reported on a recent study using light activity, education about the benign nature of pain, and encouragement to stay active. 68 At 1-year follow-up, a significantly greater number of patients in the experimental group returned to work than those who received more traditional management. Lindstrom and colleagues showed that a graded activity program reduced disability more than traditional medical intervention. 69Graded activity uses exercise to reach a quota (set amount) rather than being guided by pain (e.g., less on bad days and more on good days).

Chronic Phase—Reactivation and Exercise (after 12 Weeks)

According to the Cochrane Collaboration, evidence strongly supports activation (advice to gradually resume activities) and exercise for chronic patients. 60 One excellent study involving long-term follow-up is that of Indahl and colleagues. 14 This program provided education designed to reduce fear. Patients were informed that light activity would not injure the disk, but instead, speed recovery. The rate of returning to work was double that seen in the control group. 70 O’Sullivan and colleagues showed that specific spine stabilization exercises achieved superior outcomes to isotonic exercises (involving movement against resistance) in chronic patients with spondylolysthesis. 70 Manniche and colleagues demonstrated that an isotonic regime emphasizing endurance training was successful in improving outcomes. 71 A significant number of exercise regimes using a cognitive-behavioral approach (a structured, goal-oriented method emphasizing functional analysis and skills training) has demonstrated their effectiveness in a variety of settings.7273747576 and 77 Quota-based exercises not guided by pain were used in these studies. Interestingly, several studies have shown that exercises without a cognitive-behavioral component are less successful. 78

What is the Evidence for Passive Modalities?

Many of the most popular adjunctive treatments for acute LBP lack evidence of effectiveness. The recent Danish guidelines state, “One of the greatest errors in the treatment of LBP in this century has been the unquestioned usage of passive treatments, often-times initiated when spontaneous recovery has already begun.”8Passive modalities rely completely, or in large part, on intervention by the doctor, in contrast to active modalities (such as exercise) in which the patient’s effort constitutes the primary intervention. Passive modalities such as electrical muscle stimulation, ultrasound, diathermy, and traction were recommended only as optional. Although such passive modalities may engender higher levels of patient satisfaction, they have not been demonstrated to improve outcomes related to recovery. 3 Thus similar to routinely taking x-rays, patients may like passive modalities. However, because passive treatment does not improve outcomes, better patient education about appropriate management techniques for acute LBP is needed. 2,4,5

UNDERSTANDING SPINE STABILITY

How Does Injury Occur?

Injury occurs when applied loads exceed tissue tolerance. The spinal column devoid of its musculature has been found to buckle at a load of only 90 newtons (approximately 20 lb) at L5. 79 However, during routine activities, loads 20 times greater are encountered on a routine basis. Panjabi writes, “This large load-carrying capacity is achieved by the participation of well-coordinated muscles surrounding the spinal column.”80 Not surprisingly, the motor control system functions well when under a load. Muscles stabilize joints by stiffening in a manner similar to the rigging on a ship. However, when load is at a minimum, such as when the body is relaxed or a task is trivial, the motor control system may be caught off guard, and injuries are often precipitated. 21

Agonist-Antagonist Muscle Imbalance

Agonist-antagonist muscle co-activation is a central aspect of joint stability. Dysfunction of agonist (the muscle acting as prime mover) and antagonist (the muscle opposing the prime mover) will compromise joint stability. Early research on the elbow and knee showed that antagonist muscle co-activation is important for helping ligaments in maintaining joint stability. 81A well-known fact is that certain muscles such as those in the knee, lumbar spine, or cervical spine respond to inflammation or injury by becoming inhibited or developing atrophy.8283 and 84 Also commonly accepted is that other muscles such as the upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid (SCM), and lumbar erector spinae respond to injury or overload by tensing or becoming overactive.8586 and 87

Lund and colleagues theorized that when pain is present, a decreased activation of muscles occurs during movements in which they act as agonists, and increased activation occurs during movements in which they are antagonists. 88 In a wide variety of studies involving such diverse locomotor tasks as gait, trunk bending, mastication, head raising, reaching, and carrying activities, agonist inhibition, synergist substitution, and antagonist overactivity have repeatedly been demonstrated.86899091 and 92 (Synergist muscles complement the activity of the prime mover.) For instance, Jull has shown that when chronic neck pain develops after whiplash, during cervicocranial flexion maneuvers, the deep neck flexors are inhibited, and the sternocleidomastoid muscles are overactivated. 86

Spine Stabilizers

Specific muscles have been shown to stabilize the low back in various situations: (1) the rotators and intertraversarii have been shown to resist twisting movements; (2) the pars thoracis component of both the iliocostalis lumborum and longissimus thoracis can produce the greatest amount of extensor moment with a minimum of compressive penalty to the spine; and (3) the multifidus creates extensor torque but only at individual joints. 93 Anteriorly, the oblique abdominal muscles are involved in twisting, side bending, and stabilizing when the spine is being axially compressed.9495 and 96 Surprisingly, the one muscle that is highly active during tasks involving flexion, extension, and lateral bending is the quadratus lumborum. 96 This muscle’s architecture is ideally suited to be a stabilizer because it attaches each transverse process to the more rigid pelvis and rib cage, thereby facilitating a bilateral buttressing effect for the vertebrae. 93

Interestingly, strength (not coordination and endurance) between agonist and synergist muscles plays a pivotal role in resisting injury. Two muscles that have been studied extensively are the multifidus and transverse abdominus. The multifidus has been shown to be atrophied in patients with acute LBP. 83 This atrophy was ipsilateral to the pain and at the same segmental level as palpable joint dysfunction. Recovery from acute pain did not automatically result in restoration of the normal girth of the muscle. However, spinal stabilization exercises did successfully rebuild the muscle’s size. 43 Recent research demonstrates that individuals who successfully restore normal multifidus girth have fewer recurrences of LBP at both 1- and 2-year follow-up. 42

EMG studies have shown that the transverse abdominus was recruited before any other abdominal muscle when the trunk was subjected to sudden destabilizing forces. 97 In a study that examined abdominal activity during upper limb movements, the transverse abdominus was the only muscle active before initiation of arm motions. 98 The same result was found to be true during lower limb movements. 97

Rood first proposed that muscles can be grouped into broad categories on the basis of their functional characteristics. 99 Certain muscles were hypothesized to function as stabilizers and others as mobilizers. In recent decades Janda100,101 and Sahrmann102 promoted the concept that muscle imbalance is a key dysfunction in altering movement patterns and influencing joint stability and pain. Janda suggested that certain muscles had a tendency to become overactive, and others tended to become inhibited. The author had observed that individuals with neurologic diseases such as cerebral palsy have predictable spasticity in certain muscles (e.g., short thigh adductors) and, in conditions such as polio predictable paralysis, occurs in other muscles (e.g., abdominal wall). Janda also noted that these same tendencies were seen in individuals without neurologic disease who were either highly sedentary or were training their muscles inappropriately.

Muscle imbalance has a neurodevelopmental basis. The neonatal fetal position is maintained by tonic contraction (sustained, low-level muscle activity) of trunk and extremity flexors and extremity adductors and internal rotators. Reciprocal inhibition (Sherrington’s law), which is present in early infancy, inhibits the antagonists of the tonic muscle chains, thus maintaining muscle imbalance. As the infant develops, the reciprocal inhibition becomes dampened, thus allowing the phasic muscle system (brief, forceful muscle activity) to activate (failing in cerebral palsy). As the reflex-bound infant begins to develop his or her postural control system, tonic activity of muscles that maintain the fetal posture is superceded by agonist-antagonist co-activation of muscles necessary for movement control and production of the upright posture. Thus extensors, abductors, and external rotators co-activate with their fetal partners to stabilize joints in centrated postures and allow neurodevelopment of posture.

Bergmark summarized the scientific evidence that muscles can be divided into two broad categories based on their function, one functioning to produce movement and the other to control movement. 103 Superficial muscles are responsible for producing voluntary movement or torque production, and deep muscles are responsible for maintaining joint stability. The deep (intrinsic) muscles are responsible for joint stability on an involuntary or subcortical basis, and movement production is largely a voluntary act. The following charts show the different divisions of muscles according to their dysfunctional tendencies (Box 14-3).

Box 14-3

MUSCLE SYSTEM CLASSIFICATIONS

GLOBAL—SUPERFICIAL MUSCLES: TYPICALLY BECOME OVERACTIVE OR SHORTENED

Gastro-soleus

Adductors

Hamstrings

Tensor fascia lata

Hip flexors

Piriformis

Quadratus lumborum (lateral)

Rectus abdominus

External obliques

Lateral and thoracolumbar erector spinae

Upper trapezius

Levator scapulae

Pectorals

Subscapularis

Suboccipitals

SCM

Lateral pterygoids

Masseters

LOCAL—DEEP MUSCLES: TYPICALLY BECOME INHIBITED OR LENGTHENED

Quadratus plantae

Peronei

Vastus medialis

Gluteals

Transverse abdominus

Internal oblique

Multifidus

Quadratus lumborum (medial)

Medial and lower erector spinae

Lower and middle trapezius

Serratus anterior

Deep neck flexors

Digastricus

From Bergmark A: Stability of the lumbar spine. A study in mechanical engineering, Acta Orthopedica Scandinavica 230:20, 1989.

CLINICAL APPLICATION

The traditional orthopedic approach to managing musculoskeletal problems focuses on treating the site of injury or pain. Orthopedics originated as a way to deal with acute, traumatic injuries in modern factories, emphasizing rest and treatment of symptoms. This approach was grounded in the Renaissance ideas of Descartes, which states that most pain occurs as a result of injury. Therefore if an activity causes pain, the activity should be avoided. From this philosophy came the adages “hurt equals harm” and “let pain be your guide.” This viewpoint forms the basis of the traditional biomedical approach to pain, which includes symptomatic treatment, rest, activity avoidance, and surgery.

With today’s epidemic of chronic, disabling pain, this traditional biomedical model is inadequate. In the 1960s Melzack and Wall104formulated the revolutionary gate control theory of pain, which demonstrates how pain is modulated in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord by both ascending facilitatory and descending inhibitory pathways, which are enkephalinergic (i.e., part of the body’s internal opiate system of pain modulation). When the descending pain inhibitory pathway is dampened, pain can be perpetuated beyond the normal course of tissue healing. This circumstance can occur from addiction to pain relievers, as well as from depression and inactivity. The biopsychosocial model focuses on reducing disability and activity intolerances caused by pain. The emphasis is on increasing the patient’s functional capabilities and psychosocial coping abilities. This approach involves persistent reassurance that the patient is not damaged, coupled with the recommendation that gradual reactivation will not only restore activity tolerance, but also accelerate recovery. Patients are advised that “hurt does not necessarily equal harm.”

Action Steps

This reactivation approach consists of four fundamental action steps (Box 14-4). First, a detailed history is taken of the patient’s activity intolerances associated with their pain. Second, a thorough examination is conducted of the functional pathologic conditions related to their activity intolerances. Third, treatment (advice, adjustment/manipulation, and exercise) is directed to restoring function to the key link, which is believed to be responsible for biomechanical overload of the pain-generating tissue. Fourth, audit (assessment) of the results takes place.

Box 14-4

FUNCTIONAL REACTIVATION ACTION STEPS

1. History of any activity intolerances

2. Assessment of relevant functional condition

3. Treatment of dysfunctional kinetic chain

4. Audit of the results

Restoring function depends on expanding the patient’s functional range (FR). The FR consists of the patient’s activity intolerances, mechanical sensitivities, and relevant functional pathologic conditions. Makingthis functional diagnosis is an essential starting point in patient care; it also facilitates regular audit of meaningful outcomes of care because each component is easily reevaluated.

The FR is limited by the patient’s aggravating movements and positions and chief motor control deficits. According to Dennis Morgan, a pioneer in spinal stabilization training, “the functional position is the most stable and asymptomatic position of the spine for the task at hand.”105 Thus, before exercise can be prescribed, a thorough history and examination of the patient’s mechanical sensitivities should be carried out. 106,107

History of Activity Intolerances

The history should identify the activity intolerances that are present. Initial inquiries regard basic functions, such as sitting, standing, walking, and bending activities. Such activity intolerances, once identified, automatically become excellent patient-centered goals of care. This identification helps the patient focus on the (dys)function instead of the pain.

Sitting or forward-bending sensitivities strongly suggest a disk problem and that self-treatment would be biased toward extension. Some patients may have a weight-bearing sensitivity, but they may be relatively pain-free in non–weight-bearing positions. Such patients may tolerate and thus benefit from recumbent exercise. 106

• Restoring those functions becomes themain goal or end point of care.

• When greeting patient on follow-up visits always ask if activity intolerances are same or different (e.g., sitting, standing, walking intolerances).

• Challenge: Can you uncover from the patient’s history what specific activity intolerances are present?

Once the patient’s activity intolerances are identified, the next step is to find the functional pathologic abnormality responsible for them. For instance, if the patient has a walking intolerance, the feet or sacroiliac regions may have relevant dysfunction that is responsible for pain with walking.

The object is to focus on the source of biomechanical overload that can cause or perpetuate symptoms in the pain-generating or injured tissue. 108 In particular, locating the specific functional anomaly or dysfunctional kinetic chain that has led to the patient’s mechanical sensitivity is crucial. 108

Mechanical Sensitivity

Initial examination of the patient should identify the movements and positions that are painful or painless. McKenzie has provided one of the best guides to exercise prescription in his description of the centralization phenomenon. According to McKenzie’s assessment method, the positions or repetitive movements that increase, decrease, or centralize symptoms should be identified. 107 The movements and positions found to aggravate symptoms are used as an audit before and after testing to assess the patient’s progress. In contrast, the pain-centralizing or pain-relieving positions and movement ranges are used for self-treatment.

Myofascial Pain

If eliciting a patient’s characteristic pain is difficult with orthopedic or range-of-motion tests, then a myofascial examination can be valuable. If active trigger points that reproduce the patient’s characteristic pain can be found, then a sure-fire treatment guide is at hand, especially as a recheck of patient response and status before and after treatment.

• As a baseline outcome for rechecks of patient status before and after treatment

• To determine the starting point of care e.g., if flexion peripheralizes symptoms and extension centralizes them, extension movements are indicated)

Identifying Key Functional Abnormalities Responsible for Pain or Activity Intolerances

The cause of 90% of spine pain is unknown. Therefore most medical guidelines recommend using the unsatisfactory label nonspecific back pain. 7,8,10 Even though most back pain is called nonspecific, assuming that this pain is psychogenic or that no cause or mechanism of injury exists would be a mistake. In fact, new research is pointing toward motor control deficits as the most promising candidates for playing an etiopathologic (causative) role in spinal disorders. *

The relevant functional conditions are those related to the pain generator or injured tissue, primarily because these are the source of biomechanical overload that eventually leads to repetitive strain of the painful tissue. 108 An example of this idea would be a patient presenting with neck pain in which the functional aspect responsible for the pain may be the head-forward posture and poor motor control of cervicocranial flexion. Another example is a patient presenting with knee pain in which the key functional condition may be a kinetic chain dysfunction whereby subtalar hyperpronation causes internal tibial rotation during gait or squatting. Thus muscle (kinesiopathologic) or joint dysfunction may be responsible for the repetitive strain of a vulnerable part of the locomotor system.

Patients often present with numerous functional abnormalities relating to poor motor control. Therefore how can the key link or relevant dysfunctional chain be identified?

TESTS OF FUNCTIONAL ABNORMALITIES OF THE MOTOR SYSTEM

A broad array of tests of the locomotor system are available (Box 14-5).

Box 14-5

FUNCTIONAL TESTS

LOWER QUARTER

Mobility of first metatarsal-phalangeal joint

Transverse arch reflex stability test of Vele

Hyperpronation of the longitudinal arch during gait

Hip extension mobility

Hip abduction coordination

Hip extension coordination

Single-leg balance

Squat (two leg)

One-leg squat

LUMBOPELVIC

Active straight leg raising

Trunk curl-up

Side bridge

Sorensen

Prone abdominal hollowing

THORAX

Arm elevation

Respiration

CERVICAL

C0-C1 flexion

OROFACIAL

Mouth opening

UPPER QUARTER

Scapulohumeral rhythm

Push-up

Lower Quarter (Legs and Trunk)

Dorsiflexion Mobility of the First Metatarsal-Phalangeal (MTP) Joints110a

Test: The patient is supine. The metatarsal bone is stabilized, and the first phalangeal bone is mobilized into dorsiflexion. Sixty-degree flexion is normal.

Clinical relevance: Decreased dorsiflexion of the first MTP joint limits the push-off phase at terminal stance because of slackening of the plantar fascia and inability to activate the windlass mechanism. The windlass mechanism occurs when the plantar fascia is tensed during the late stance phase of gait. This action aids resupination of the foot and thus helps promote a smooth early propulsive phase of the gait cycle.

Vele’s Reflex Foot Stability Test (Lower Extremity Stability) 111

Test: The patient stands with feet shoulder-width apart. The patient is requested to lean forward from his or her ankles without bending from the knees or spine (similar to a ski jumper). The clinician notes if delayed reflex gripping of the toes occurs. Asymmetry is noted.

Clinical relevance: Disturbed reflex stability of the intrinsic foot flexors, located on the sole of the foot.

Test: The patient is asked to walk a few steps. The clinician observes the medial longitudinal arch for excessive pronation during the stance phase.

Clinical relevance: Excessive pronation can lead to other faults in the kinetic chain resulting from medial bowing of the Achilles tendon, tibial torsion, and anterior pelvic tilt.

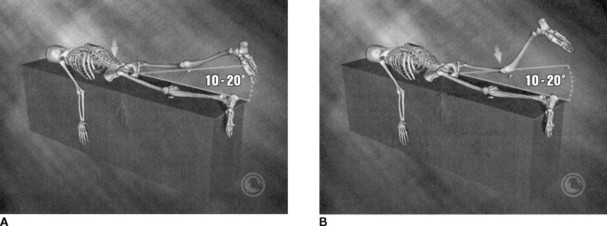

Test: The patient is positioned with his or her pelvis at the foot of the examination bench. One knee is held close to the chest to flatten the lumbar lordosis. The other leg is allowed to extend passively. Hip and knee extension mobility are noted.

Clinical relevance: Decreased hip extension mobility (less than 10 degrees) significantly alters the normal biomechanics of the toe-off or propulsive phase of gait. Decreased hip extension mobility can also lead to secondary hypermobility or repetitive overstrain of the lumbosacral spine in extension causing facet irritation.

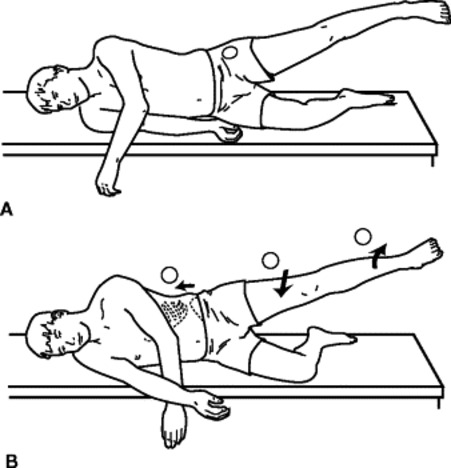

Test: While in a side-lying position, the patient slowly raises the top leg straight up to the ceiling.

|

| Fig. 14-1 Hip abduction. A, Normal—hip abduction to 45 degrees. B, Abnormal—if hip flexion, external rotation, “hiking,” or pelvic rotation takes place during movement. (Reprinted with permission from Liebenson CS: Manual resistance techniques in rehabilitation. In Chaitow L, editor: Muscle energy techniques, ed 2, Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone, 2001.) Churchill Livingstone |

Pass-Fail (PF) criteria:

• Failure if initiation occurs (with)

• Cephalad shift of the pelvis (overactive quadratus lumborum)

• Pelvic rotation

• Thigh flexion (overactive tensor fascia latae)

Clinical relevance: Poor function of the gluteus medius can increase ankle, knee, hip, or lumbopelvic instability in the transverse and frontal planes.

Test:

• Patient is in a prone position.

• One leg is raised straight up to the ceiling.

|

| Fig. 14-2 Hip extension. A, With lumbar hyperextension. B, With overactivity of the hamstrings. (Reprinted with permission from Liebenson CS, Chapman S: Lumbar spine: making a rehabilitation prescription, Baltimore, 1998, Williams & Wilkins.) Williams & Wilkins |

PF criteria:

• Failure if initiation occurs (with)

• Anterior pelvic tilt

• Lumbar rotation (or hyperextension)

• Delayed gluteus maximus contraction

• Muscular contraction above T8

• Knee flexion

Clinical relevance: Altered hip extension typically leads to overstress of the lumbar facet joints during extension and can lead to hamstring strain resulting from substitution for the gluteus maximus.

Test:

• The patient stands on one leg, with the opposite leg flexed at the hip and knee.

• The subject should be instructed to fix his or her gaze at a point on the wall directly in front of the patient.

• The patient should practice with eyes open two times for up to 10 seconds.

• The patient should then attempt to balance as long as possible on one leg with eyes closed for up to 30 seconds.

• The best score with eyes closed for each leg is recorded.

• If the subject lasts 30 seconds on the first eyes-closed attempt, he or she should make a second attempt.

• The exercise may be repeated two times for each leg to account for learning.

Quantification: Each test is timed until the subject:

• Reaches out

• Hops

• Puts foot down

• Touches the foot to weight-bearing leg

Observation: The length of time the patient stands on one leg with eyes open (maximum of 30 seconds) and then repeated with eyes closed (maximum of 30 seconds) is recorded. Both legs are tested.

Normative data:

| Age (in Years) | Eyes Open (in Seconds) | Eyes Closed (in Seconds) |

| 20–59 | 29–30 | 21.0–28.8 (average 25) |

| 60–69 | 22.5 average | 10 |

| 70–79 | 14.2 | 4.3 |

Clinical relevance: Poor balance is associated with ankle and knee instability and can predispose older adults to falls.

Dynamic Squat Test110g

Test: The patient stands with feet shoulder-width apart. Arms are outstretched. Patient is instructed to perform repetitive squats to a depth at which the thighs are horizontal. Repetitions are performed until fatigue, knee pain, or back pain stops; until the test is over; or until 50 repetitions are achieved.

Clinical relevance: Poor squat endurance is associated with stoop-lifting strategies replacing squat-lifting strategies.

Test:

• The patient stands on one foot with eyes open.

• The patient squats as deeply as possible without losing balance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree