Although its origins are lost deep in history, the practice of manipulation is close to being universal, 1 because “to massage and manipulate an aching muscle and limb”2 is a natural tendency. Only a small step separates adding pressure from rubbing an aching joint, especially when a popping noise and some degree of relief is often the reward. The first episodes of spinal manipulation certainly occurred well before the first known recordings of its use. What had been performed and orally passed on for unknown years was eventually written down.

Sociologist Walter I. Wardwell, a pre-eminent observer of chiropractic, warns about the problems of language when studying the forerunners of the chiropractic adjustment. 3 Although D.D. Palmer and chiropractors termed chiropractic manipulation the adjustment and gave it a relatively precise meaning, manipulation itself is a generic term. At various times, manipulation may refer to the reduction of a fracture, massage, mobilization, and other related activities. Unlike the chiropractic adjustment, manipulation is not limited to the spine. Ancient and modern documents frequently fail to specify the type of manipulation to which they refer.

Wardwell provides an excellent categorization system for the study of prechiropractic spinal manipulation:

The pre-Palmer literature on spinal manipulation can be put in several categories. First would be manipulative practices of ancient civilizations—Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and others. Second would be the often similar practices of primitive peoples. Third would be the bonesetters and similar folk practitioners in Western societies, some of whom practiced well into the present century. Fourth, mention will be made of the orthodox medical literature on “spinal irritation” which appeared in the nineteenth century. Finally there is osteopathy, which began pre-Palmer and is unquestionably similar to chiropractic though not identical in theory or technique. As is well known, both Palmers took great pains to differentiate chiropractic from it. 3

MANIPULATIVE PRACTICES OF ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS

Joint manipulation seems to have always been a part of Chinese medicine. 4 From the beginning it was linked to massage; only rather recently was joint manipulation separated as a distinct discipline. As in other geographic areas, its use was based on the results of empirical findings. It was perpetuated from generation to generation through the heritage and teachings of its disciples; consequently, early records of its use are fragmentary.

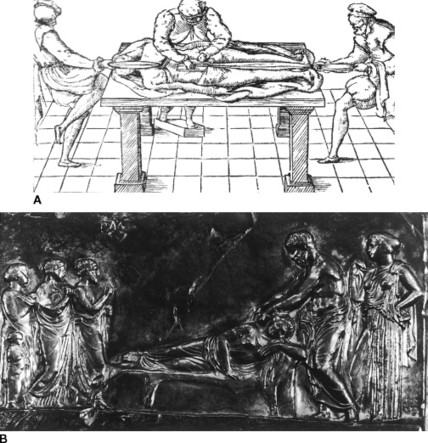

The Mongol conquest strongly influenced Chinese manipulation. The wandering, warlike Mongols developed skills necessitated by their active way of life, including the ubiquitous horseback riding involved in their far-ranging wars. However, as with any forerunner, techniques used by the ancient (and even relatively recent) Chinese practitioners would seem cumbersome or even harsh to the current chiropractor. For example, one technique for torticollis used one hand to steady the head while the other held the chin, thereby extending the neck in a gross maneuver4 (Fig. 1-1).

|

| Fig. 1-1 Lumbar manipulation during the use of gravity traction as practiced in ancient China. (From The Golden Mirror of Medicine.) |

D.D. Palmer was aware of Chinese medicine. He recorded an incident involving a Chinese “houseboy” suffering from cholera. He stated that the Chinese healer “was prodding him [the houseboy] under the tongue with a long needle,”5 and he also recorded having seen a physiologic chart used in Chinese medicine. Nevertheless, no definitive evidence suggests that the Chinese influenced Palmer’s adjusting.

Other Eastern medical traditions, including those of India, also contained forms of spinal manipulation. However, manipulation of joints was usually performed by bath attendants, because it was considered a part of hygiene, not a medical procedure. 6 In fairness, it should be noted that preventive measures such as hygiene, diet, and proper living are of great importance in Ayurvedic (Indian) medicine, not simply peripheral items as observed during periods of recent history.

Although most modern chiropractors, osteopathic practitioners, and medical manipulators are proud to trace their lineage to Hippocrates (fifth century), the techniques he used bear little resemblance to modern methods. A minority opinion advanced by K.A. Ligeros, MD, PhD, claims that Hippocrates and Greek physicians of Hippocrates’ day actually performed manipulation of the spine in a manner similar to that performed by chiropractors today. 6 Ligeros appears to extrapolate the facts of Hippocrates’ knowledge of the spine and nervous system, as well as his recorded use of manipulation, to a point in which similarities to modern chiropractic manipulation seem inevitable. Ligeros states that the methods rediscovered and known as chiropractic were also known and practiced by Aesculapius and his followers 420 years before the Christian era. A famous votive relief depicting Aesculapius manipulating a person’s upper thoracic spine serves as part of Ligeros’ proof. 7 However, little further evidence supports the view of a proto-chiropractic discipline during that era. Most historians might agree with Elizabeth Lomax who states, “Only further scholarly research could establish whether the Greeks merely attempted to reposition vertebrae displaced through trauma, the conventional interpretation, or indeed frequently manipulated spines as therapy for a wide variety of dysfunctions.”8 It is still interesting to note that D.D. Palmer referred to Aesculapius and his teachings as a foundation for what he termed chiropractic5 (Fig. 1-2).

|

| Fig. 1-2 A, Typical spinal manipulation from classical Greek period into the seventeenth century. B, Votive relief depicting Aesculapius manipulating an individual’s upper thoracic spine. (A courtesy Biblioteca Universitaria, Aarchiginnas, Bologna, Italy. B courtesy Palmer College of Chiropractic, Library Special Collections.) |

The Persian physician and philosopher Avicenna (ad 980–1037), known as Ibn Sina, also used and wrote of manipulation. His work was, for all practical purposes, a rewrite of Galen’s that, in turn, was descended from that of Hippocrates. 9

Pierre Gaucher-Peslherbe wrote, “Well into the seventeenth century and regardless of whether they were Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Cretan, Arabic, Spanish, Turkish, Italian, French, or German, all published authors resorted to the same method. The patient was bandaged and lay on a board; traction was applied toward the head and feet while pressure was exerted onto a selected spinal area.”6 The pressure or thrust was delivered by using the practitioner’s hands, feet, or even buttocks by simply sitting on the patient’s spine. Occasionally, a piece of wood might have also been used as a lever.

Forms of manipulation practiced among primitive peoples were similar to these practiced in ancient civilizations, but they were often accompanied by more extensive religious ritual or magic. The interconnection of religion and healing was always present. In reference to manipulation, Gaucher-Peslherbe quotes the noted anthropologist, Mircea Eliade, “…throughout history bones and joints have been invested with a symbolic and mystical significance.”10

Chester Wilk in his book Chiropractic Speaks Out recounts Captain Cook’s story of how the techniques of “pummeling and squeezing” used by Tahitian women relieved his crippling rheumatism. 11 The ancient custom of children and small adults walking on an individual’s back has been documented in many areas of the world, including North and South America, Polynesia, Asia, and Bohemia, where it was known as a “peasant practice.”12 The use of manipulation has also been documented in the Americas.

From the records of the early Spanish Friars of the sixteenth century, chiropractor and anthropologist C.W. Weiant relates that Aztecs distinguished between what they called a “true doctor” and a “false doctor” or witch doctor. One of the qualifications for true doctors was their knowledge of how the joints worked properly. 13

North American Indians predating the Jamestown settlement (1607) used forms of manipulation as a part of daily life. Stories of their appreciation of spinal manipulation have become so commonplace that they have crept into popular literature. In a novel on Lewis and Clark’s early nineteenth century expedition, James Alexander Thom relates how Clark kept the Nez Perce busy for most of a day “adjusting” their spines, anachronistically using Palmer’s word for spinal manipulation, which would not come into common usage until after another century had passed. 14

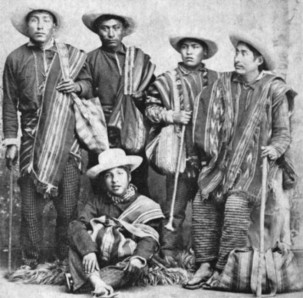

In South America, Ronald L. Firestone cites evidence of extensive use of manipulation in pre-Columbian culture (Firestone R, e-mail communication to author, 11/19/01). “One of the best indicators of such would be the prevalence of this method in the current practices of the Quechua and Aymara traditional practitioners.” Firestone shows great respect for these practitioners, known as Callahullas or Yatiri (Fig. 1-3). Describing the work of these practitioners from an innovative perspective, he suggests, “I actually think that we in chiropractic should begin referring to those who practice, or have practiced, in this manner as traditional chiropractors since medicine refers to its empirical practitioners as traditional medicine.”

|

| Fig. 1-3 The Callahullas, or Yatiri, of South America. (Courtesy Ronald Firestone, D.C.) |

BONESETTING

The earliest known text on bonesetting was published by the Friar Moulton in 1656 and republished by Robert Turner. The book, despite its lengthy title, The Compleat Bone-Setter, Wherein the Method of Curing Broken Bones and Strains and Dislocated Joynts, together with Ruptures, Commonly Called Bellyes, is fully demonstrated. Revised, enlarged, and published in English (1665 edition), it had only two pages that described manipulative techniques. 15 Although The Compleat Bone-Setter was written during a period in which physicians still used manipulation, the book merely commended its use but did not teach it. Most of the teaching was left to one-on-one contact.

Lomax states that manipulation was ubiquitous, and its utility was not seriously questioned until the eighteenth century. 8 She attributes spinal manipulation’s falling out of favor with medical physicians to the tuberculosis caries of the spine, which were frequently diagnosed during this period. Eminent physicians, such as Sir Percival Pott, believed all spinal deformities should be presumed to be caused by caries and therefore should not be manipulated. They considered it malpractice to do so, stating clearly that the preferred treatment for spinal deformities should be rest and induced local ulceration.

Not all historians agree with Lomax as to the reason manipulation fell from grace; they only agree that it did. Johan Schultes, who died in 1645, was the last published author to teach spinal manipulation as a part of regular medicine. 15 Although the discontinuation of manipulation by medical physicians took place over a period of more than 100 years, no evidence of its use after the end of the seventeenth century can be found. Johannes Fossgreen suggests another cause may have been fear of contagious contact. 15 This argument is supported by evidence from physicians in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, distancing themselves from their patients in the wake of such contagious diseases as the highly virulent form of syphilis brought back to Europe from the Americas by the adventurers who had themselves introduced smallpox to the American Indians.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree