Chapter 148 Surgical Treatment of Benign Bone Lesions

Benign bone lesions about the knee are relatively common entities. These lesions can be a cause of pain, deformity, and emotional distress. Often, the treatment of these lesions is straightforward, with little associated morbidity.7 The knee is an extremely common location for most benign bone tumors. They present in a variety of ways, from incidental findings on radiographs to pain and deformity. A thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation of the patient with a bone lesion is critical (see Chapter 147). This chapter focuses on the surgical treatment of the common benign bone lesions about the knee for the general orthopedic surgeon as well as for the musculoskeletal oncologist.

Staging of Benign Bone Tumors

Led by Dr. William Enneking, staging systems were developed for benign and malignant bone tumors. The three-stage system for the staging of benign bone tumors is widely used for the description and, more importantly, to guide treatment of benign bone tumors.24The system is based on the biologic behavior of these tumors determined by examination of the radiographic findings.68

Treatment of Specific Benign Conditions

Benign Bone-Forming Tumors

Osteoid Osteoma

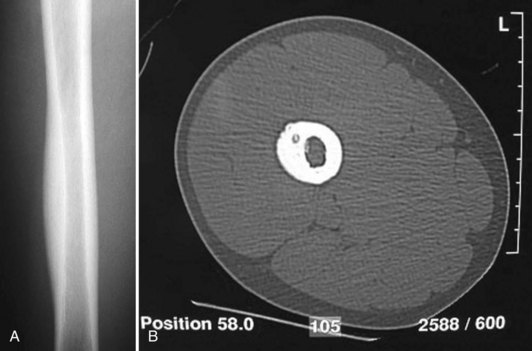

The characteristic radiographic feature of an osteoid osteoma is a central lytic nidus that can measure up to 1 cm in diameter. In the common cortical lesion (Fig. 148-1), there will be an extensive reactive sclerosis creating a fusiform bulge on the bone surface. If the nidus is more centrally located in metaphyseal bone, less sclerosis is seen and the radiographic appearance is less diagnostic. Technetium bone scans are invariably positive. A computed tomography (CT) scan is helpful to locate the lesion better anatomically for improved preoperative planning.5 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may miss the nidus, making establishment of the diagnosis more difficult.28

Osteoid osteomas have been attributed to otherwise unexplainable knee pain.29,41 If the nidus is close to a joint or within the joint, which can occur in approximately 15% of cases,3,45 inflammatory synovitis may result. This synovitis may inappropriately suggest the diagnosis of pyarthrosis or rheumatoid arthritis.85 If the bony reaction is focal and intense, the lesion can take on the appearance of an exostosis.55 Furthermore, an osteoid osteoma can mimic pes anserinus syndrome, when the lesion is located medially in the proximal tibia.72

Generally, symptoms are relieved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) secondary to a high concentration of prostaglandins in the nidus.17,18,33,63,90 Osteoid osteoma may have a unique pathogenic nerve supply as well, a finding that may be common among bone tumors.53,65

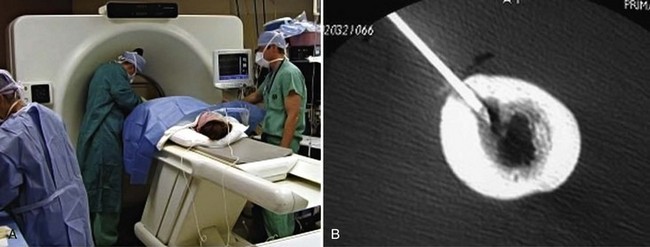

Most cases of osteoid osteomas are stage 1 lesions because they resolve spontaneously. They can be treated symptomatically with aspirin or NSAIDs.8 If the patient fails nonsurgical treatment, surgical intervention is usually successful. If surgery is elected, it is important to eradicate the entire symptomatic nidus. Removal of a large amount of the surrounding sclerotic bone should be avoided because it can severely weaken the bone and may result in an iatrogenic pathologic fracture. For open techniques with regard to cortical lesions, adequate exposure is required to enable the surgeon to visualize the bulging cortex. Intralesional resection via the burr-down technique is generally preferred over en bloc resection. The nidus can be identified visually by the hyperemic pink color in the adjacent reactive bone. It is imperative to carry out curettage on the nidus followed by high-speed burring to advance the margin another 2 to 3 mm. If the lesion is not visible on the surface, which is usually the case in medullary lesions, radiographic markers should be placed intraoperatively prior to making the cortical window. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation is another less invasive method of treating osteoid osteoma and is my preferred method of treatment (Fig. 148-2). This technique continues to gain wide acceptance as a preferable management modality.13,19–21,47,76 Depending on location, CT guidance may be necessary, and is often extremely helpful to obtain successful eradication of the lesion.57 In cases in which there is an intra-articular lesion, arthroscopic treatment has been used successfully in adults and children.1,26,45,61

Osteoblastoma

An osteoblastoma is a large osteoid osteoma. The nidus of a true osteoblastoma is larger than 1 cm.27 Its incidence about the knee is less than osteoid osteoma and accounts for 1% of all bone tumors overall. Osteoblastomas arise more commonly in males than in females and occur in the same age group as osteoid osteomas.87 Infrequently, osteoblastomas are found in the metaphyses of the distal femur, which should raise the suspicion for more ominous diagnoses. The most common presenting symptom is pain, and the lesion is considered can be latent to locally aggressive.4

The treatment modalities for osteoblastomas are similar to those used to treat osteoid osteomas. Treatment usually consists of a vigorous curettage of the lesion, which may require a bone graft if instability results because of the relative size of the lesion after mechanical or thermal expansion of the margin. Radiofrequency ablation may also prove useful in the management of this lesion and is currently being used at many centers.17,46

Osteofibrous Dysplasia

Radiographically, the lytic changes seen in the anterior tibial cortex are surrounded by sclerotic margins, creating a soap bubble appearance similar to the radiographic picture of fibrous dysplasia and adamantinoma. Some studies have suggested that osteofibrous dysplasia may be a precursor to adamantinoma.* Histologically, the lytic lesion shows a benign, trabecular, alphabet soup pattern in a fibrous stroma. The histologic findings are similar to those in fibrous dysplasia, although the lesions of fibrous dysplasia lack the prominent surface layer of rimming osteoblasts seen in osteofibrous dysplasia. The two can be distinguished by a variety of clinical, immunohistochemical,52,78 and molecular markers.79 These lesions are usually latent or active and, rarely, locally aggressive, because there is a relatively wide spectrum of disease.

Surgical treatment in osteofibrous dysplasia should be reserved for patients in whom the disease is poorly controlled with conservative treatment or those who have a high possibility of impending fracture and progression of their deformity.67 Early attempts at surgical curettage and grafting may result in a high failure rate because of recurrence. It is generally suggested that if intervention is necessary, it should be deferred until the patient reaches adolescence, when there is an improved chance that the disease may be arrested following surgery.88

Benign Cartilage-Forming Tumors

Enchondroma

An enchondroma refers to a centrally located benign cartilage neoplasm of medullary bone.50 These tumors are relatively common lesions, accounting for more than 10% of all benign bone tumors. Approximately 50% of cases arise in the small tubular bone of the hands and feet, with the next most common locations being the proximal humerus and distal femur. An enchondroma develops in a growing bone as a hamartomatous process. It is frequently asymptomatic and may avoid detection until the patient reaches adulthood. The lesion is usually discovered as an incidental finding on a routine radiographic examination, MRI for arthrographic examination or, more rarely, in association with a pathologic fracture.

Radiographs of enchondromas show geographic lysis of normal trabecular bone, with sharp margination and central stippled calcification (Fig. 148-3). Infrequently, there is associated pain, cortical scalloping, and dilation of the bone by a large tumor. When such features are present, one must be concerned about the possibility of a chondrosarcoma. Enchondromas are latent or active lesions.50 If a lesion is considered to be locally aggressive, it is much more likely to be chondrosarcoma, and referral for treatment is universally warranted.

Enchondromatosis, or Ollier’s disease, is a rare nonfamilial dysplasia with multiple enchondromas that is typically seen on half of the body and may be similar to fibrous dysplasia. When it is bilateral, one side tends to be more involved than the other. This condition can be extensive, with significant involvement of metaphyseal areas, resulting in bowing and shortening of the long bones (Fig. 148-4). Such dramatic changes are rarely seen in cases of a solitary enchondroma. Varus deformities can be severe and may be managed by a variety of techniques.16

A large solitary enchondroma in a large bone will convert to a low-grade chondrosarcoma in fewer than 5% of cases. If malignant transformation does occur, it will invariably take place during adulthood, and is very rarely in the short bones of the hands and feet. A secondary chondrosarcoma in enchondromatosis can arise in up to 20% of cases and may be related to inactivation of particular tumor suppressor genes.12

Patient with solitary enchondromas are treated symptomatically. If the patient has a pathologic fracture, it is usually best to allow the fracture to heal and perform a simple curettage and bone grafting procedure at a later date. This usually results in good function and a low chance of recurrence. Patients with Ollier’s disease or Maffucci’s disease (enchondromatosis associated with soft tissue hemangiomas) must be followed carefully because of the increased risk of malignant degeneration. This transformation usually occurs over a period of decades, and is more common in the long bones.10–12

Periosteal Chondroma

A periosteal chondroma is a benign cartilage lesion seen on the surface of a bone. Patients may have multiple lesions, with the most common location being on the proximal humerus. The distal femur is a relatively common site, and intra-articular involvement has been reported.30,34,77 Radiographically, periosteal chondromas often have a thin shell of bone and appear to lie on the cortical surface (Fig. 148-5). These lesions are latent or active, and should be treated with observation. Periosteal chondromas can grow to be relatively large. A lesion larger than 4 cm suggests a peripheral primary chondrosarcoma and should be referred to a tumor specialist.

Figure 148-5 AP radiograph of the knee shows a periosteal chondroma of the anteromedial distal femur.

Osteochondroma

The three components of an osteochondroma include the cartilage cap, perichondrium, and bony stalk or base.74 The bony stalk of an osteochondroma is in direct communication with the medullary canal of the bone from which it arises, which is an essential component of correctly diagnosing these lesions. Osteochondromas can be pedunculated (narrow base), as is commonly seen around the knee (Fig. 148-6), or can be sessile (broad base). An associated cartilaginous cap on the bony base is required to make the diagnosis of osteochondroma. This cap has the histologic features of a normal growth plate during the growing years and is the only neoplastic portion of the osteochondroma. Osteochondroma growth plate activity subsides at the same time as the activity in the larger plate from which the osteochondroma arose.

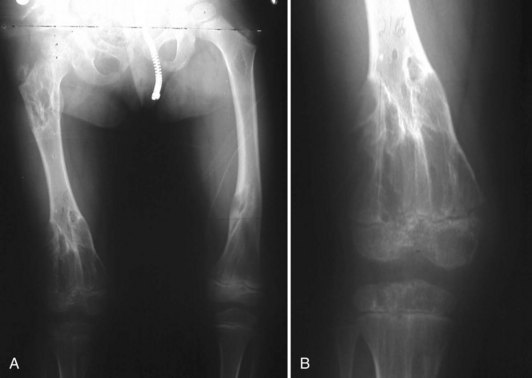

A familial form of osteochondroma, multiple hereditary exostoses (MHE), is an autosomal dominant disorder that is 10% as common as a solitary osteochondroma, affecting 1 to 2 patients/100,000.83 Three genetic loci have been determined to be involved with MHE involving the EXT gene, the most common being EXT1 and EXT2. This condition can vary from mild to extensive and may involve symmetrical limb shortening and deformity in all extremities. Valgus knee deformity has been reported to be a common manifestation that may require corrective osteotomy.81 The metaphyseal portions of long bones are often deformed and widened (Fig. 148-7). The histologic findings in multiple exostoses are similar to those in solitary osteochondromas.

Conversion of a solitary osteochondroma to a chondrosarcoma occurs only during adulthood in less than 1% of cases. The overall rate of conversion for all types of solitary lesions is rare.40 In MEH, there is a 1% to 5% chance of malignant conversion to secondary chondrosarcoma especially in the larger, more proximal lesions (Fig. 148-8). However, this conversion rate is highly variable based on many years of literature reports.32

Figure 148-8 A and B, Malignant degeneration of proximal fibular osteochondroma that enlarged rapidly and became painful in a 70-year-old patient with multiple hereditary exostoses. Note the aggressive appearance compared with Figure 148-7.

Solitary osteochondromas are latent lesions. Symptoms are caused secondary to mechanical effects on surrounding structures. Most children and adults with solitary osteochondromas are asymptomatic and therefore do not require surgical treatment. In some cases, the lesion may be palpable and irritating, as well as cosmetically unsettling.81 Surgical removal is appropriate in these cases to address the symptoms. Removal of the tumor as a prophylaxis for chondrosarcomatous degeneration is not recommended. Symptomatic lesions in patients with MHE are also addressed surgically as needed. Corrective osteotomy is occasionally required because of angulatory deformity about the knee—and loss of pronosupination of the forearm should be examined closely in children.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree