Chapter 27 Coccygeal Subluxation Syndrome

After reading this chapter you should be able to answer the following questions:

| Question 1 | What is the correlation between coccygeal angulation and coccy-dynia? |

| Question 2 | What procedures may be used for treatment of coccygeal syndrome? |

Coccygeal subluxation syndrome, also referred to as coccygodynia or coccygalgia, is a term used to describe pain in and around the coccyx that does not radiate and is made worse by sitting or by standing up from a seated position.1–3 For the purposes of this chapter the term coccydynia will be used. While treatment of the coccyx is taught in undergraduate chiropractic programs, chiropractic research and case reporting on clinical considerations involving this area is limited. Perhaps this chapter will contribute to a greater interest in research on this challenging clinical presentation.

Coccydynia, first described as a pathologic entity by Petit in 1726 and later clinically by Simpson in 1859,1,4,5 is part of the urogenital and rectal pain syndromes. As a group of syndromes, including rectal pain, perineal pain, and vulvodynia, they can be difficult to diagnose and often the etiology is not found.3 Adding to this diagnostic challenge for the chiropractor is the relationship described by several authors between coccydynia and low back pain.3,6,7 Malbohan7 reported that the pelvic diaphragm was clinically involved in nearly all of the 1500 cases of low back pain that they studied. Postacchini and Massobrio6 studied normal radiographic anatomy involving 120 symptomatic patients, including a retrospective review of 51 patients who had a partial or total coccygectomy. They noted that conflicting results have been reported regarding the effectiveness of surgical treatment of the coccyx and the presence of coexisting low back pain. In a study involving 50 patients, Wray3 observed that “virtually all” of the patients with CT evidence of lumbosacral disc prolapse were “cured” by local treatment of the coccyx.

The coccygeal syndrome is part of a larger group of syndromes that can be described as occasionally controversial with questions ranging from whether they exist to whether they are purely psychosomatic.5 The causes and best therapeutic approaches to coccydynia are the focus of renewed interest especially with regard to area of pain management.1 However, only a small number of clinical series have been published and much of the information on coccydynia is scattered in various disciplines. Therefore the clinical approach to managing coccygeal pain remains challenging.

Anatomic Considerations

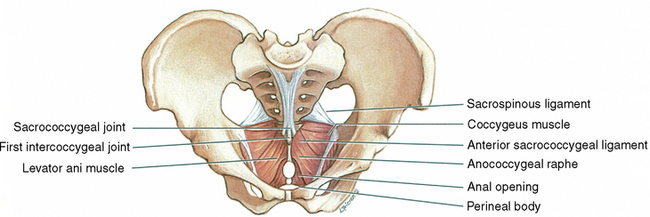

The coccyx consists of usually four rudimentary vertebrae. Variations in segments of one less or one more also exist. The shape of the coccyx was seen as beaklike by early observers. The term coccyx is derived from the Greek word for cuckoo. The three inferior coccygeal segments often fuse in middle age. In old age the first coccygeal segment often fuses to the sacrum.8 The pelvic diaphragm and its immediate surroundings constitute the major muscular considerations when dealing with the coccyx. For general purposes the pelvic diaphragm is formed by the levator ani and coccygeus muscles (Figure 27-1 and Figure 27-2).

Levator Ani

• Origin: Pelvic surface of the body of the pubis to the ischial spine

• Insertion: The central perineal tendon, the wall of the anal canal, the anococcygeal ligament, the coccyx

• Action: Raise the pelvic floor. This action assists the abdominal muscles in compressing the abdominal contents. This is important in coughing, vomiting, urinating, and trunk fixation during strong movements of the upper limbs such as lifting.

• Innervation: Third and fourth sacral nerves and the inferior rectal nerve

Coccygeus

This muscle forms the posterior and smaller part of the pelvic diaphragm.

• Insertion: Lateral aspect of the fifth sacral vertebra and coccyx

• Action: Supports the coccyx and pulls it forward after defecation and childbirth

The ligaments associated with the coccyx include the sacrotuberous, the sacrospinous, and the anococcygeal. In addition to their coccygeal attachments, the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments help resist sacral flexion (between the innominates) caused by gravitational effects of erect posture. Sandoz9 refers to these structures as “check ligaments” of nutation. These two ligaments reinforce and add strength to the sacroiliac joint capsule.10 The anococcygeal ligament is the median fibrous intersection of components of the levator ani muscle. It is located between the anal canal and the coccyx. (See Figures 27-1 and Figures 27-2.) The actual configuration of the coccyx, particularly as seen on the lateral radiograph, shows an interesting pattern of variation including the fusion pattern of the coccygeal segments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree