Assessment of Posture

Postural Development

Through evolution, human beings have assumed an upright erect or bipedal posture. The advantage of an erect posture is that it enables the hands to be free and the eyes to be farther from the ground so that the individual can see farther ahead. The disadvantages include an increased strain on the spine and lower limbs and comparative difficulties in respiration and transport of the blood to the brain.

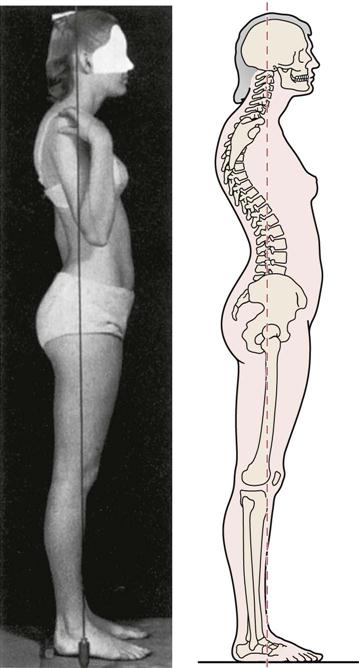

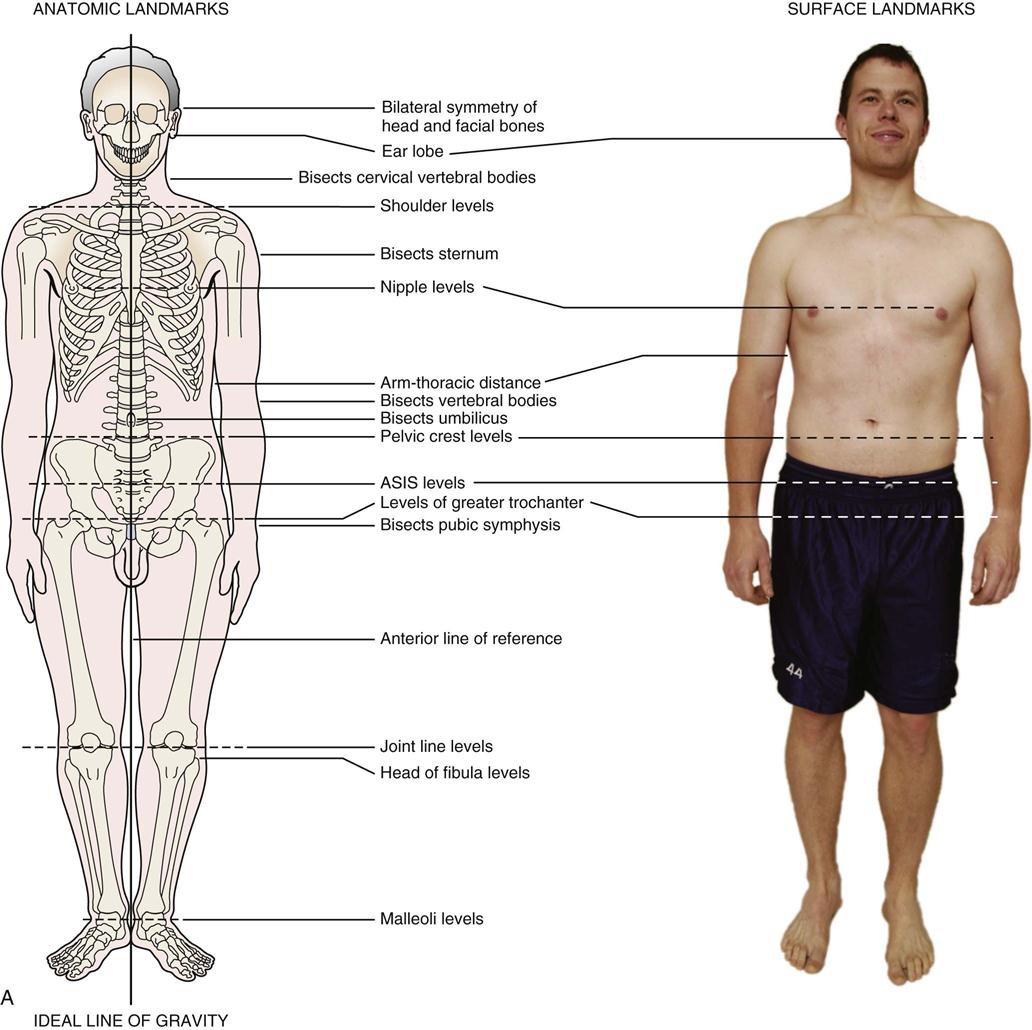

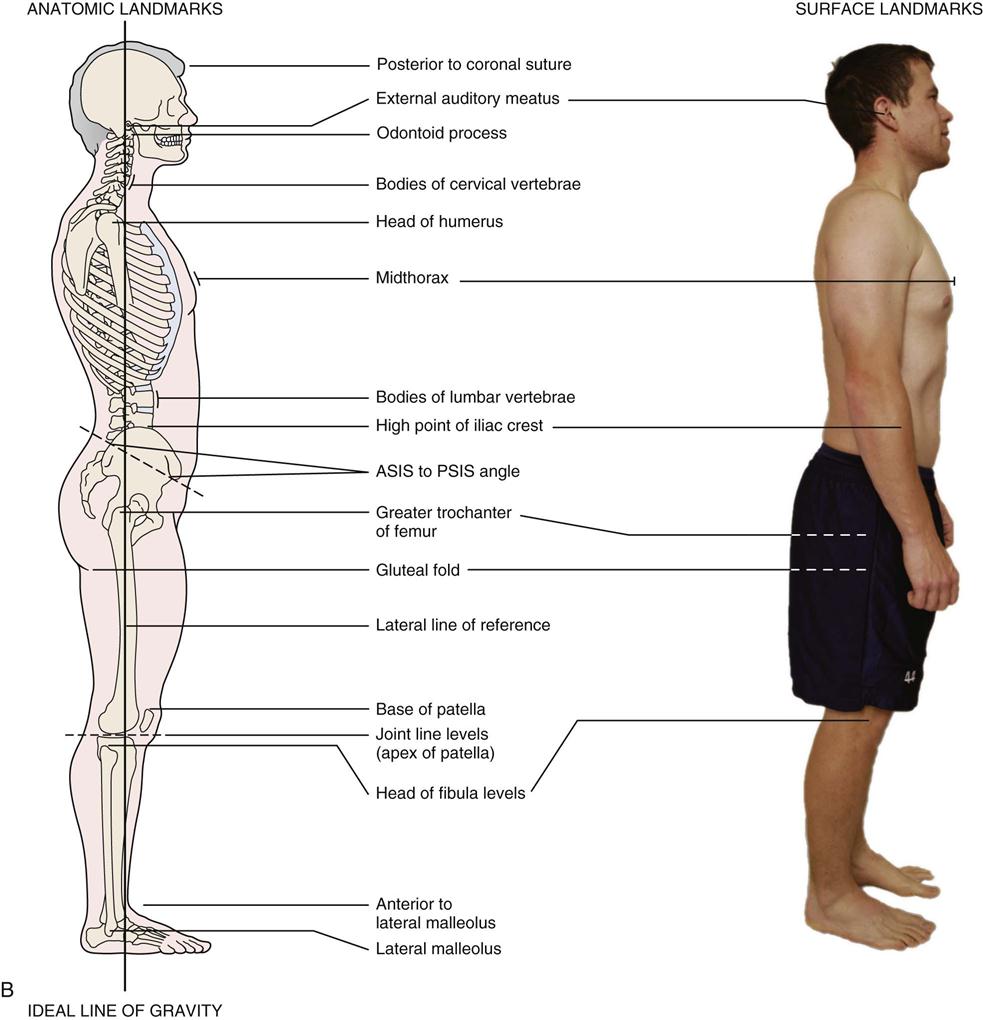

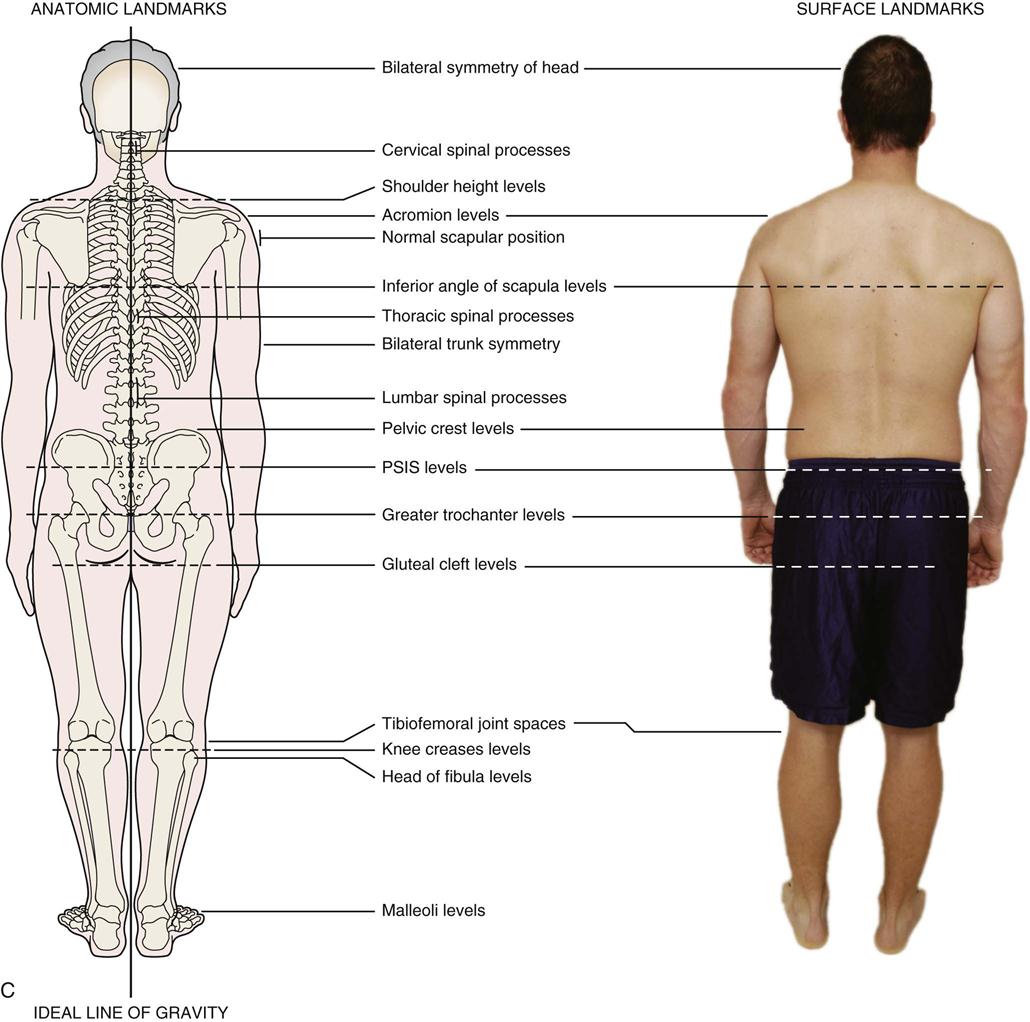

Posture, which is the relative disposition of the body at any one moment, is a composite of the positions of the different joints of the body at that time. The position of each joint has an effect on the position of the other joints. Classically, ideal static postural alignment (viewed from the side) is defined as a straight line (line of gravity) that passes through the earlobe, the bodies of the cervical vertebrae, the tip of the shoulder, midway through the thorax, through the bodies of the lumbar vertebrae, slightly posterior to the hip joint, slightly anterior to the axis of the knee joint, and just anterior to the lateral malleolus (Figure 15-1).1 Correct posture is the position in which minimum stress is applied to each joint. Upright posture is the normal standing posture for humans. Although upright posture allows one to see farther and provides freedom to move the arms, it does have disadvantages. It places greater stress on the lower limbs, pelvis, and spine; reduces stability; and increases the work of the heart.2 If the upright posture is correct, minimal muscle activity is needed to maintain the position.

A, Front view. On a typical patient note the difference in shoulder height and nipple height and apparent arm length difference, arm-thorax difference, and difference in out-toeing. B, Side view. Typical patient with good lateral alignment. C, Back view. On a typical patient note the difference in shoulder slope, shoulder height, height of inferior scapular angles, and rotation of arms. In this view, also note straight Achilles tendons.

Any static position that increases the stress to the joints may be called faulty posture. If a person has strong, flexible muscles, faulty postures may not affect the joints because he or she has the ability to change position readily so that the stresses do not become excessive. If the joints are stiff (hypomobile) or too mobile (hypermobile), or the muscles are weak, shortened, or lengthened, however, the posture cannot be easily altered to the correct alignment, and the result can be some form of pathology. The pathology may be the result of the cumulative effect of repeated small stresses (microtrauma) over a long period of time or of constant abnormal stresses (macrotrauma) over a short period of time. These chronic stresses can result in the same problems that are seen when a sudden (acute) severe stress is applied to the body. The abnormal stresses cause excessive wearing of the articular surfaces of joints and produce osteophytes and traction spurs, which represent the body’s attempt to alter its structure to accommodate these repeated stresses. The soft tissue (e.g., muscles, ligaments) may become weakened, stretched, or traumatized by the increased stress. Thus postural deviations do not always cause symptoms, but over time, they may do so.3 The application of an acute stress on the chronic stress may exacerbate the problem and produce the signs and symptoms that initially prompt the patient to seek aid.

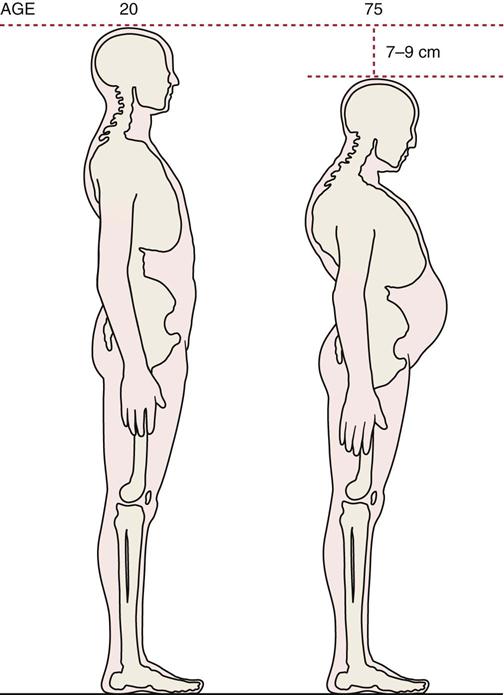

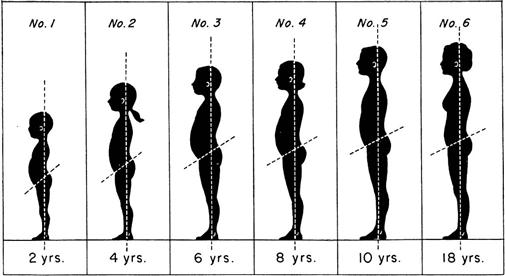

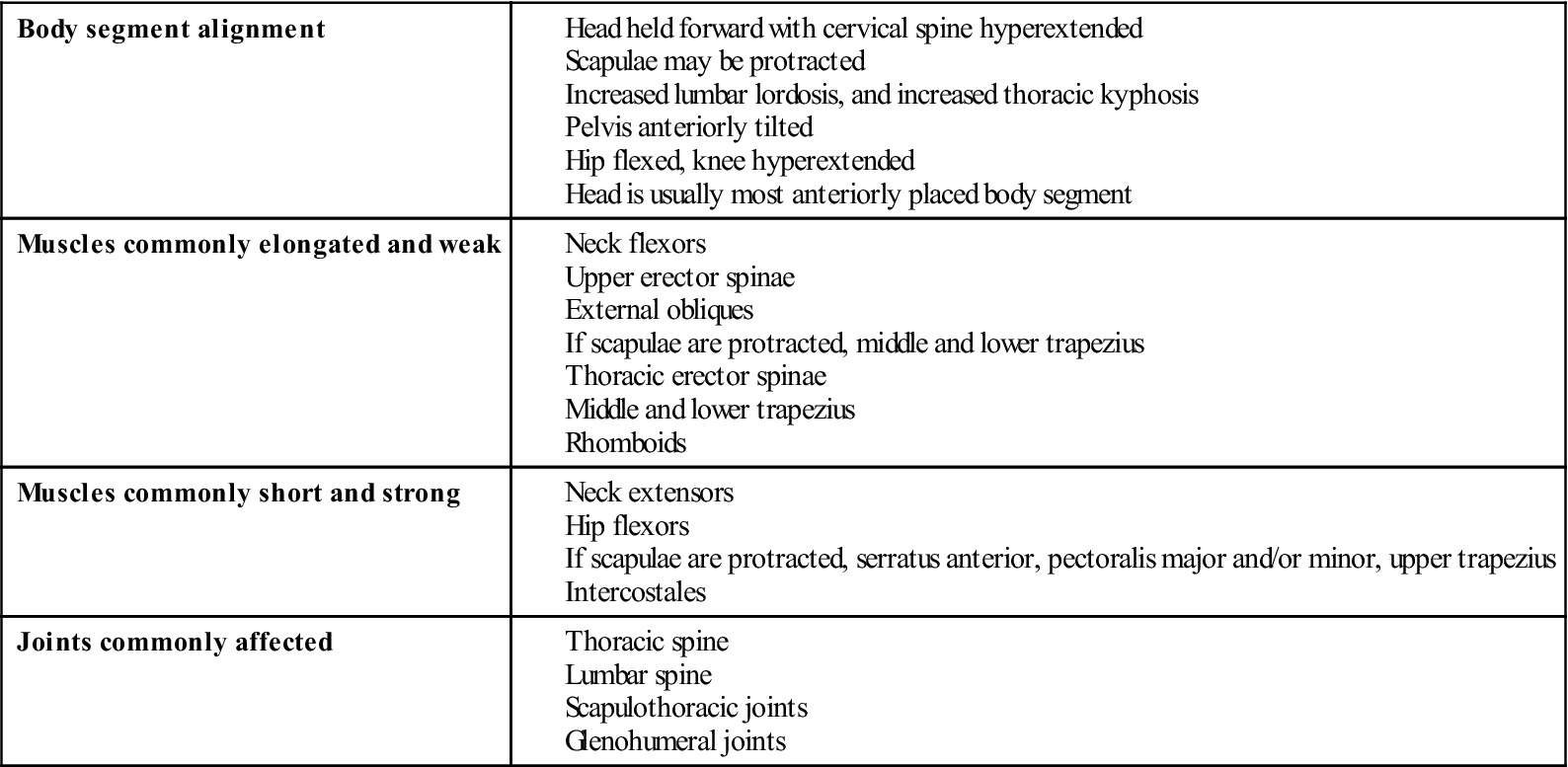

At birth, the entire spine is concave forward, or flexed (Figure 15-2). Curves of the spine found at birth are called primary curves. The curves that retain this position, those of the thoracic spine and sacrum, are therefore classified as primary curves of the spine. As the child grows (Figure 15-3), secondary curves appear and are convex forward, or extended. At about the age of 3 months, when the child begins to lift the head, the cervical spine becomes convex forward, producing the cervical lordosis. In the lumbar spine, the secondary curve develops slightly later (6 to 8 months), when the child begins to sit up and walk. In old age, the secondary curves again begin to disappear as the spine starts to return to a flexed position as the result of disc degeneration, ligamentous calcification, osteoporosis, and vertebral wedging.

A, Flexed posture in a newborn. B, Development of secondary cervical curve. C, Development of secondary lumbar curve. D, Sitting posture.

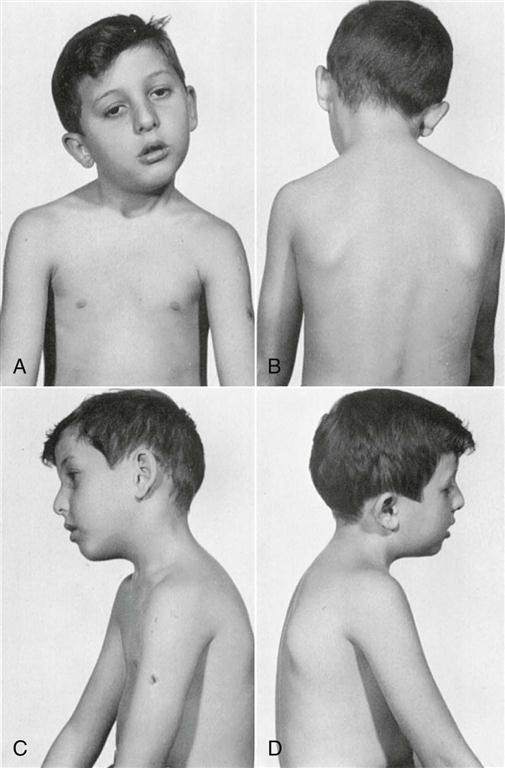

Apparent kyphosis at 6 and 8 years is caused by scapular winging. (From McMorris RO: Faulty postures. Pediatr Clin North Am 8:214, 1961.)

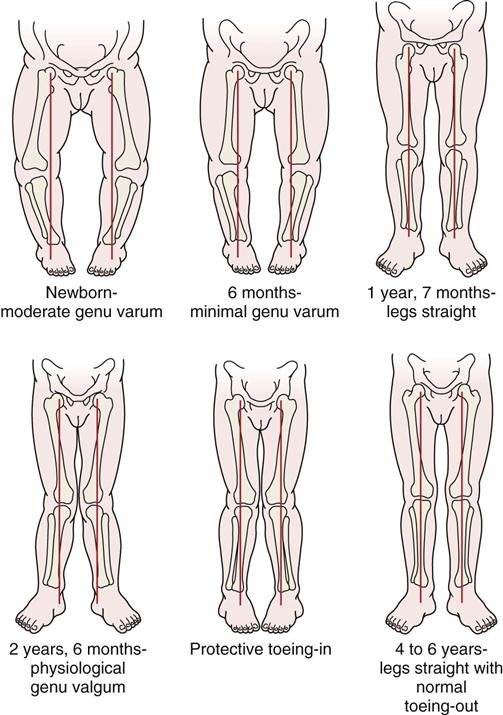

In the child, the center of gravity is at the level of the twelfth thoracic vertebra. As the child grows older, the center of gravity drops, eventually reaching the level of the second sacral vertebra in adults (slightly higher in males). The child stands with a wide base to maintain balance, and the knees are flexed. The knees are slightly bowed (genu varum) until about 18 months of age. The child then becomes slightly knock kneed (genu valgum) until the age of 3 years. By the age of 6 years, the legs should naturally straighten (Figure 15-4). The lumbar spine in the child has an exaggerated lumbar curve, or excessive lordosis. This accentuated curve is caused by the presence of large abdominal contents, weakness of the abdominal musculature, and the small pelvis characteristic of children at this age.

Initially, a child is flatfooted, or appears to be, as the result of the minimal development of the medial longitudinal arch and the fat pad that is found in the arch. As the child grows, the fat pad slowly decreases in size, making the medial arch more evident. In addition, as the foot develops and the muscles strengthen, the arches of the feet develop normally and become more evident.

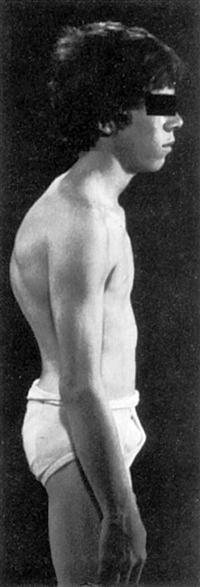

During adolescence, posture changes because of hormonal influence with the onset of puberty and musculoskeletal growth. Human beings go through two growth spurts, one when they are very young and a more obvious one when they are in adolescence. This second growth spurt lasts 2.5 to 4 years.4 During this period, growth is accompanied by sexual maturation. Females develop quicker and sooner than males. Females enter puberty between 8 and 14 years of age, and puberty lasts about 3 years. Males enter puberty between 9.5 and 16 years of age, and it lasts up to 5 years.2 It is during this period that body differences arise between males and females with males tending toward longer leg and arm length, wider shoulders, smaller hip width, and greater overall skeletal size and height than females. Because of the rapid growth spurt, individuals, especially males, may appear ungainly, and poor postural habits and changes are more likely to occur at this age.

Factors Affecting Posture

Several anatomical features may affect correct posture. These features may be enhanced or cause additional problems when combined with pathological or congenital states, such as Klippel-Feil syndrome, Scheuermann disease (juvenile kyphosis), scoliosis, or disc disease.

Causes of Poor Posture

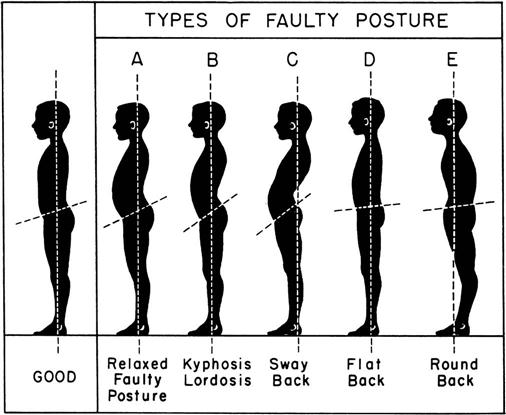

There are many examples of poor posture (Figure 15-5). Some of the causes are postural (positional), and some are structural.

Postural (Positional) Factors

The most common postural problem is poor postural habit; that is, for whatever reason, the patient does not maintain a correct posture. This type of posture is often seen in the person who stands or sits for long periods and begins to slouch. Maintenance of correct posture requires muscles that are strong, flexible, and easily adaptable to environmental change. These muscles must continually work against gravity and in harmony with one another to maintain an upright posture.

Another cause of poor postural habits, especially in children, is not wanting to appear taller than one’s peers. If a child has an early, rapid growth spurt there may be a tendency to slouch so as not to “stand out” and appear different. Such a spurt may also result in the unequal growth of the various structures, and this may lead to altered posture; for example, the growth of muscle may not keep up with the growth of bone. This process is sometimes evident in adolescents with tight hamstrings.

Muscle imbalance and muscle contracture are other causes of poor posture. For example, a tight iliopsoas muscle increases the lumbar lordosis in the lumbar spine.

Pain may also cause poor posture. Pressure on a nerve root in the lumbar spine can lead to pain in the back and result in a scoliosis as the body unconsciously adopts a posture that decreases the pain.

Respiratory conditions (e.g., emphysema), general weakness, excess weight, loss of proprioception, or muscle spasm (as seen in cerebral palsy or with trauma, as examples) may also lead to poor posture.

The majority of postural nonstructural faults are relatively easy to correct after the problem has been identified. The treatment involves strengthening weak muscles, stretching tight structures, and teaching the patient that it is his or her responsibility to maintain a correct upright posture in standing, sitting, and other activities of daily living (ADLs).

Structural Factors

Structural deformities that are the result of congenital anomalies, developmental problems, trauma, or disease may cause an alteration of posture. For example, a significant difference in leg length or an anomaly of the spine, such as a hemivertebra, may alter the posture.

Structural deformities involve mainly changes in bone and therefore are not easily correctable without surgery. However, patients often can be relieved of symptoms by proper postural care instruction.

Common Spinal Deformities

Lordosis

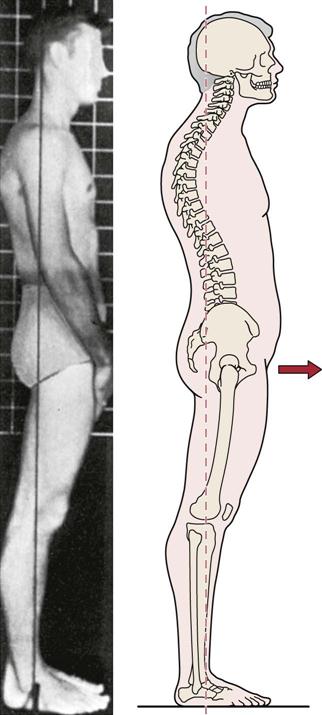

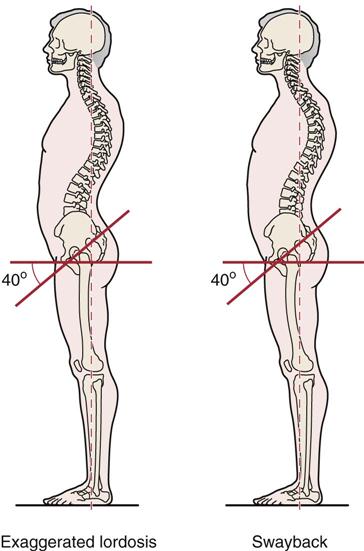

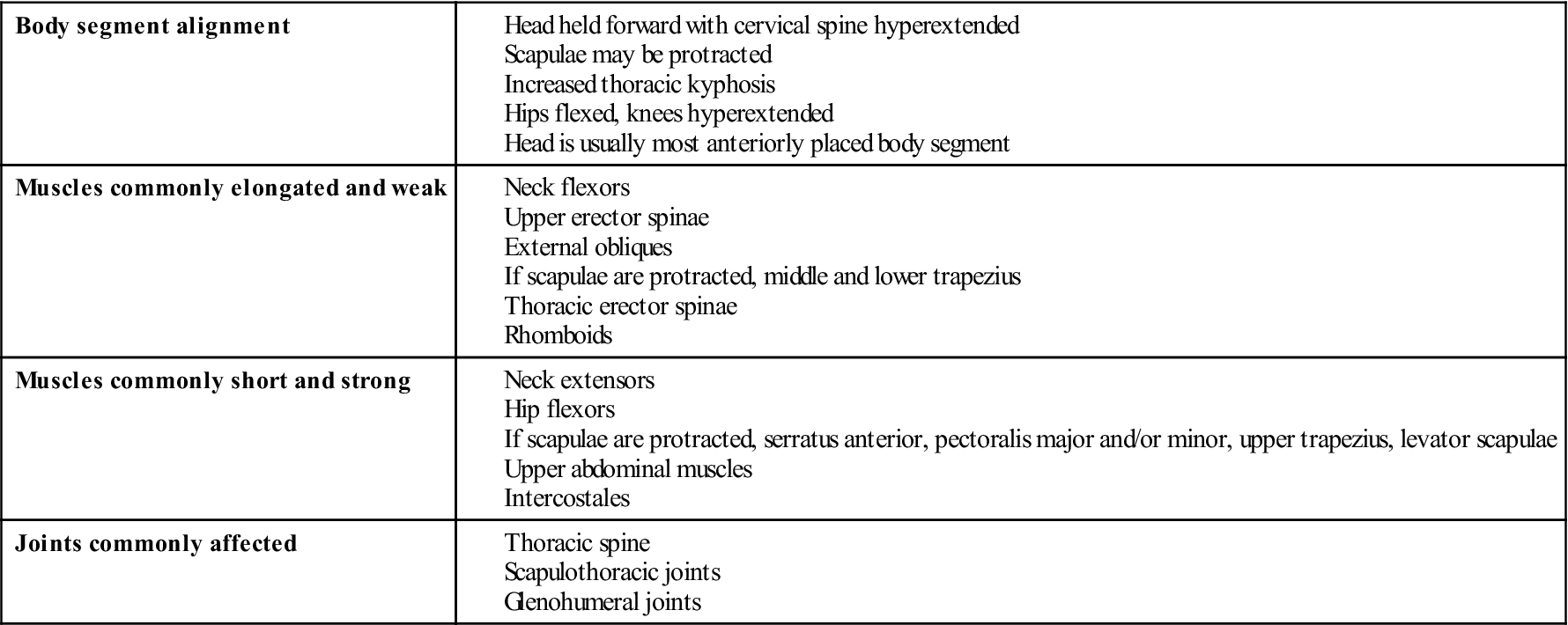

Lordosis is an anterior curvature of the spine (Figure 15-6).5–9 Pathologically, it is an exaggeration of the normal curves found in the cervical and lumbar spines. Causes of increased lordosis include (1) postural or functional deformity; (2) lax muscles, especially the abdominal muscles, in combination with tight muscles, especially hip flexors or lumbar extensors (Table 15-1); (3) a heavy abdomen, resulting from excess weight or pregnancy; (4) compensatory mechanisms that result from another deformity, such as kyphosis (Figure 15-7); (5) tight and commonly strong muscles (see Table 15-1); (6) spondylolisthesis; (7) congenital problems, such as bilateral congenital dislocation of the hip; (8) failure of segmentation of the neural arch of a facet joint segment; or (9) fashion (e.g., wearing high-heeled shoes). There are two types of exaggerated lordosis, pathological lordosis and swayback deformity.

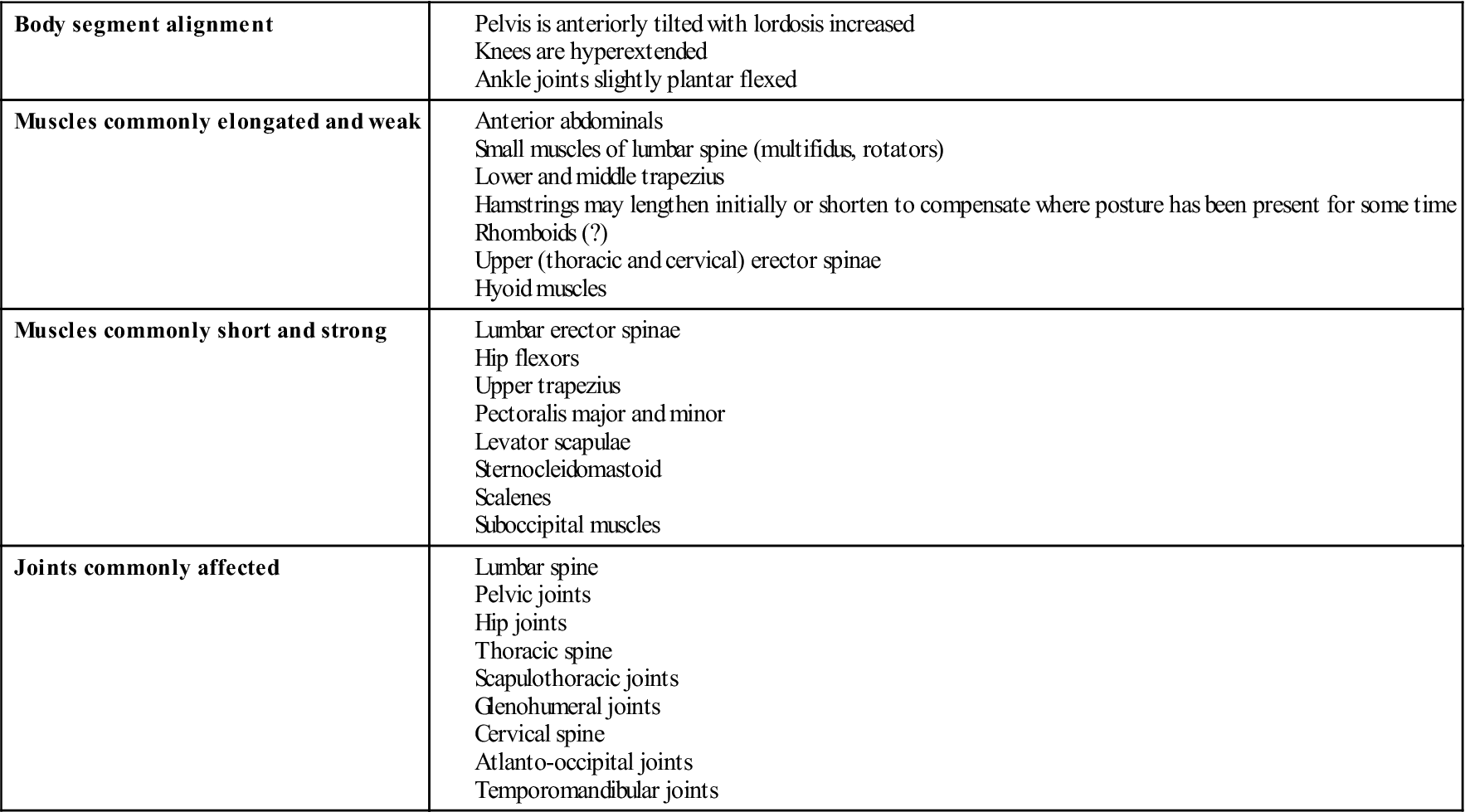

TABLE 15-1

Changes Associated with Pathological Lordosis

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Pathological Lordosis.

In the patient with pathological lordosis, one may often observe sagging shoulders (scapulae are protracted and arms are medially rotated), medial rotation of the legs, and poking forward of the head so that it is in front of the center of gravity (Figure 15-8). This posture is adopted in an attempt to keep the center of gravity where it should be. Deviation in one part of the body often leads to deviation in another part of the body in an attempt to maintain the correct center of gravity and the correct visual plane. This type of exaggerated lordosis is the most common postural deviation seen.

The pelvic angle, normally approximately 30°, is increased with lordosis. With excessive or pathological lordosis, there is an increase in the pelvic angle to approximately 40°, accompanied by a mobile spine and an anterior pelvic tilt. Exaggerated lumbar lordosis is usually accompanied by weakness of the deep lumbar extensors and tightness of the hip flexors and tensor fasciae latae combined with weak abdominals (see Table 15-1).10

Swayback Deformity.

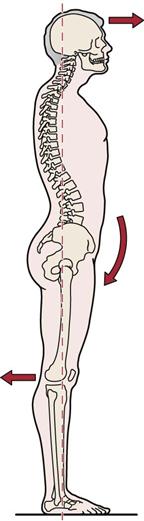

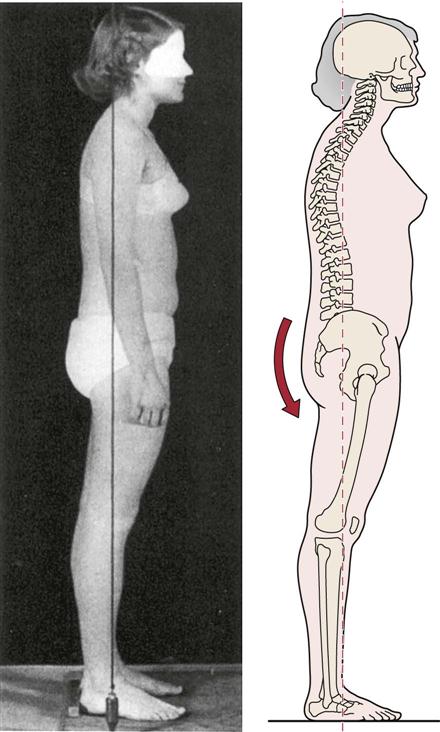

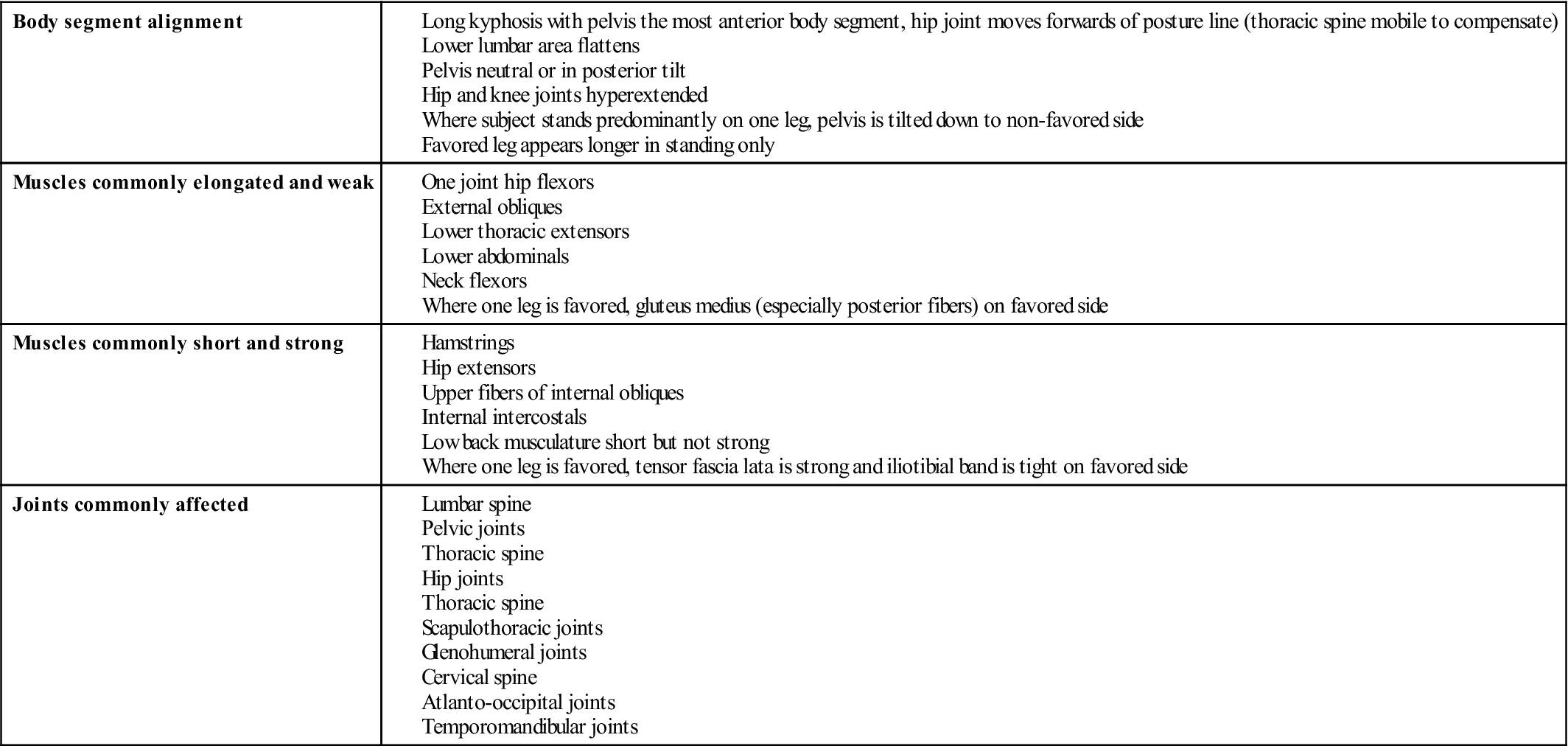

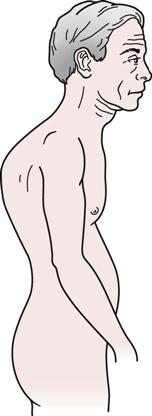

With a swayback deformity, there is increased pelvic inclination to approximately 40°, and the thoracolumbar spine exhibits a kyphosis (Figure 15-9). A swayback deformity results in the spine’s bending back rather sharply at the lumbosacral angle. With this postural deformity, the entire pelvis shifts anteriorly, causing the hips to move into extension. To maintain the center of gravity in its normal position, the thoracic spine flexes on the lumbar spine. The result is an increase in the lumbar and thoracic curves. Such a deformity may be associated with tightness of the hip extensors, lower lumbar extensors, and upper abdominals, along with weakness of the hip flexors, lower abdominals, and lower thoracic extensors (Table 15-2).1

TABLE 15-2

Changes Associated with Swayback

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Kyphosis

Kyphosis is a posterior curvature of the spine (Figures 15-10 and 15-11).7,9,11–15 Pathologically, it is an exaggeration of the normal curve found in the thoracic spine. There are several causes of kyphosis, including tuberculosis, vertebral compression fractures, Scheuermann disease, ankylosing spondylitis, senile osteoporosis, tumors, compensation in conjunction with lordosis, and congenital anomalies.11 The congenital anomalies include a partial segmental defect, as seen in osseous metaplasia, or centrum hypoplasia and aplasia.14,16,17 In addition, paralysis may lead to a kyphosis because of the loss of muscle action needed to maintain the correct posture combined with the forces of gravity.

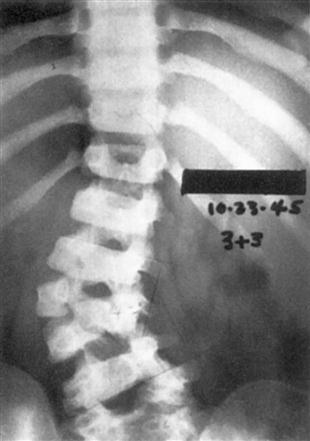

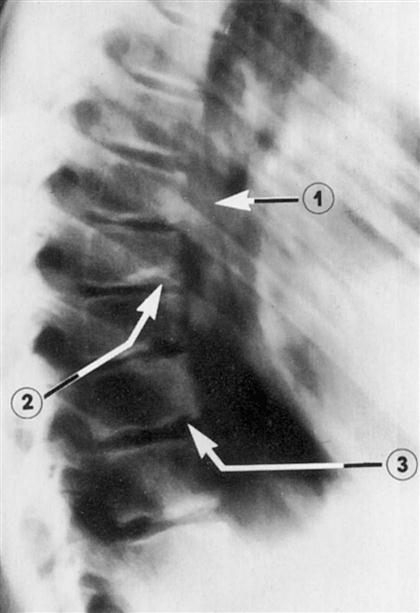

Pathological conditions, such as Scheuermann vertebral osteochondritis, may also result in a structural kyphosis (Figure 15-12 ). In this condition, inflammation of the bone and cartilage occurs around the ring epiphysis of the vertebral body. The condition often leads to an anterior wedging of the vertebra. It is a growth disorder that affects approximately 10% of the population, and in most cases several vertebrae are affected. The most common area for the disease to occur is between T10 and L2.

Note the wedged vertebra (1), Schmorl nodules (2), and marked irregularity of the vertebral end plates (3). (From Moe JH, Bradford DS, Winter RB, et al: Scoliosis and other spinal deformities, Philadelphia, 1978, WB Saunders, p. 332.)

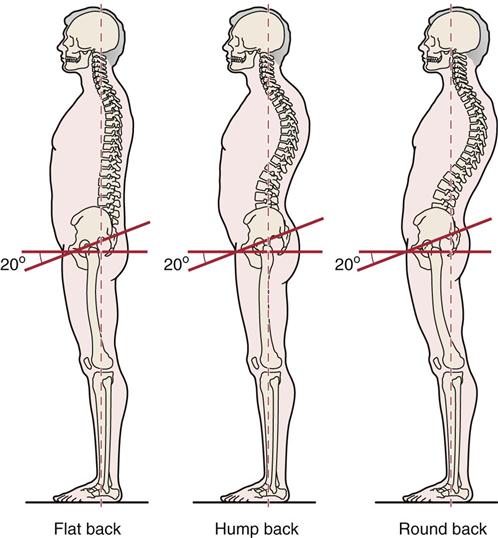

The four types of kyphosis are round back, humpback, flat back, and dowager’s hump.

Round Back.

The patient with a round back has a long, rounded curve with decreased pelvic inclination (less than 30°) and thoracolumbar kyphosis. The patient often presents with the trunk flexed forward and a decreased lumbar curve (Figure 15-13). On examination, there are tight hip extensors and trunk flexors with weak hip flexors and lumbar extensors (Table 15-3).

TABLE 15-3

Changes Associated with a Round Back Form of Kyphosis

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Humpback or Gibbus.

With humpback, there is a localized, sharp posterior angulation in the thoracic spine (Figure 15-14). This is commonly a structural deformity as the result of a fracture or pathology.

Flat Back.

A patient with flat back has decreased pelvic inclination to 20° and a mobile lumbar spine (Figure 15-15). Table 15-4 outlines the structures affected.

TABLE 15-4

Changes Associated with a Flat Back Form of Kyphosis

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Dowager’s Hump.

Dowager’s hump is often seen in older patients, especially women. The deformity commonly is caused by osteoporosis, in which the thoracic vertebral bodies begin to degenerate and wedge in an anterior direction, resulting in a kyphosis (Figure 15-16).

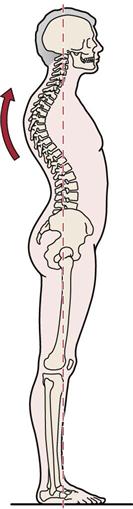

Kypholordotic Posture.

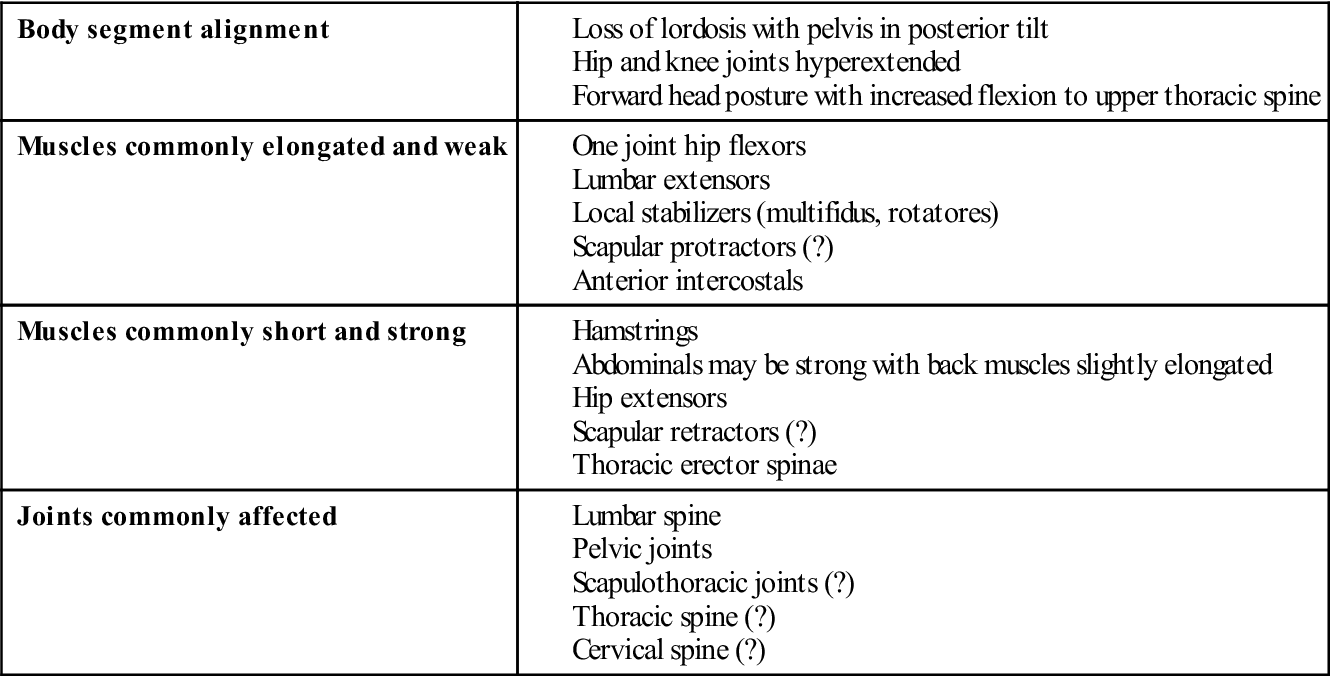

In some cases, both the thoracic and lumbar spine may be affected. Figure 15-17 and Table 15-5 outline the changes seen with this posture.

TABLE 15-5

Changes Associated with Kypholordotic Posture

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Scoliosis

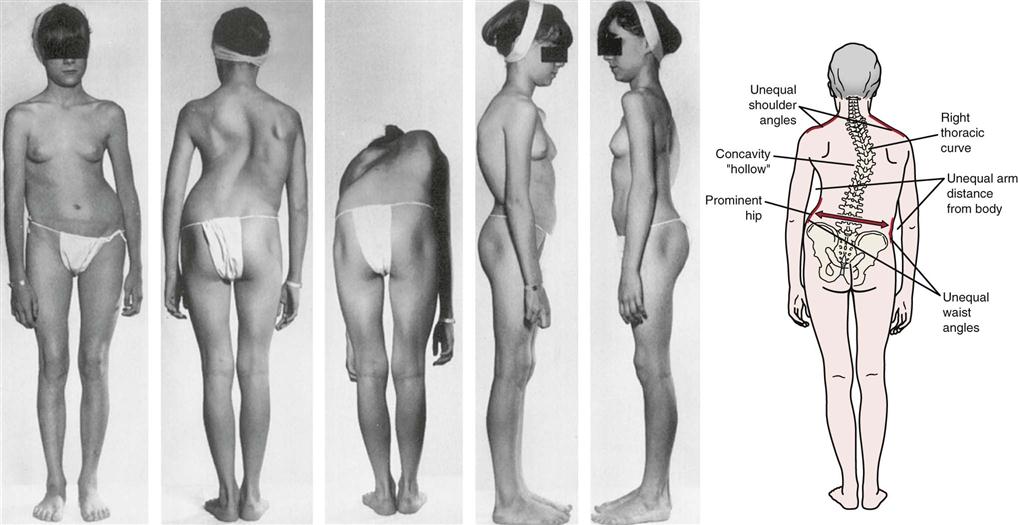

Scoliosis is a lateral curvature of the spine.11,13,18–24 This type of deformity is often the most visible spinal deformity, especially in its severe forms. The most famous example of scoliosis is the “hunchback of Notre Dame.” In the cervical spine, a scoliosis is called a torticollis. There are several types of scoliosis, some of which are nonstructural (Figure 15-18) and some of which are structural. Nonstructural or functional scoliosis may be caused by postural problems, hysteria, nerve root irritation, inflammation, or compensation caused by leg length discrepancy or contracture (in the lumbar spine) (Table 15-6).23 Structural scoliosis primarily involves bony deformity, which may be congenital or acquired, or excessive muscle weakness, as seen in a person with long-term quadriplegia. This type of scoliosis may be caused by wedge vertebra, hemivertebra (Figure 15-19), or failure of segmentation. It may be idiopathic (genetic) (Figure 15-20); neuromuscular, resulting from an upper or lower motor neuron lesion; or myopathic, resulting from muscular disease; or it may be caused by arthrogryposis, resulting from persistent joint contracture,17 or by conditions such as neurofibromatosis, mesenchymal disorders, or trauma. It may accompany infection, tumors, and inflammatory conditions that result in bone destruction. Torticollis may occur because of neuromuscular problems, because of congenital problems (abnormal sternocleidomastoid muscle), or in conjunction with malocclusion of the temporomandibular joints or with ear problems (referred to the cervical spine).

Note the contracted sternocleidomastoid muscle. (From Tachdjian MO: Pediatric orthopedics, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders, p. 74.)

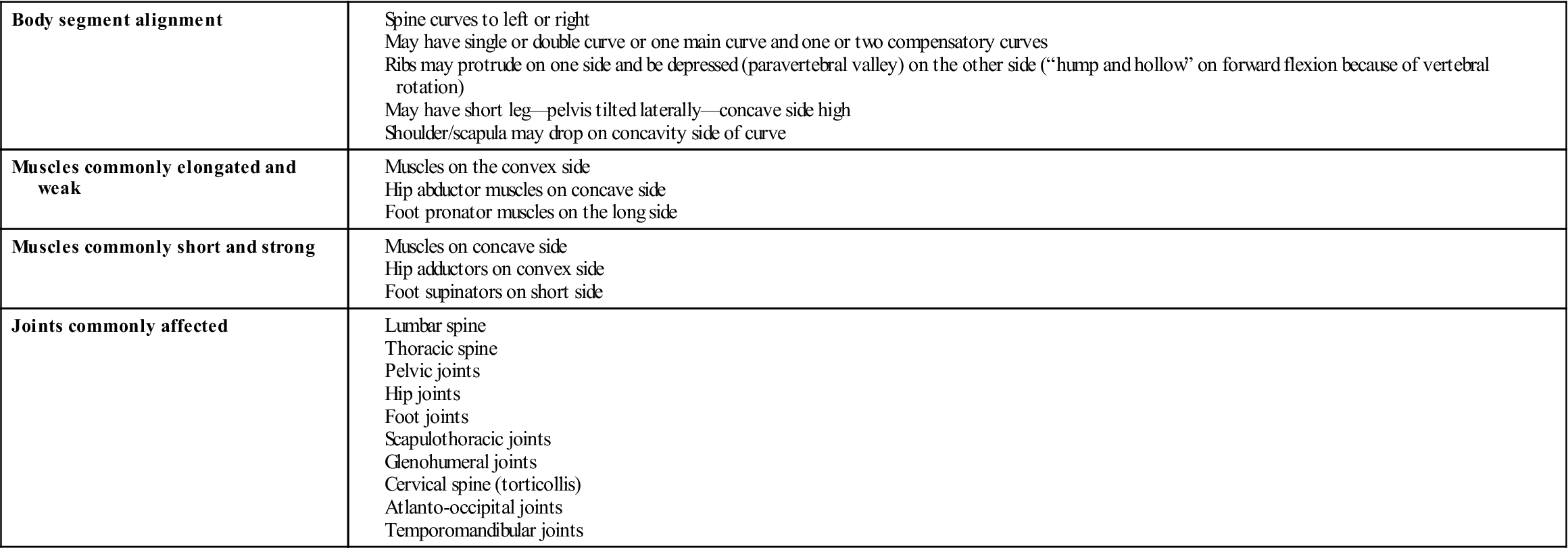

TABLE 15-6

Changes Associated with Postural Scoliosis

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Line drawing shows prominent features of scoliosis. (Photographs from Tachdjian MO: Pediatric orthopedics, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders, p. 1200.)

With structural scoliosis, the patient lacks normal flexibility, and side bending becomes asymmetrical. This type of scoliosis may be progressive, and the curve does not disappear on forward flexion. It is most commonly seen in the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine. With nonstructural scoliosis, there is no bony deformity; this type of scoliosis is not progressive. The spine shows segmental limitation, and side bending is usually symmetrical. The nonstructural scoliotic curve disappears on forward flexion. This type of scoliosis is usually found in the cervical, lumbar, or thoracolumbar area.

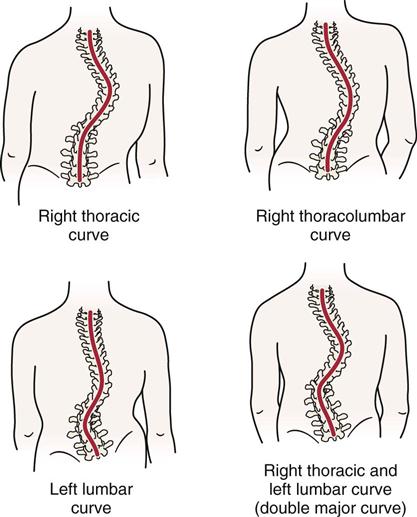

Idiopathic scoliosis accounts for 75% to 85% of all cases of structural scoliosis. The vertebral bodies rotate into the convexity of the curve with the spinous processes going toward the concavity of the curve. There is a fixed rotational prominence on the convex side, which is best seen on forward flexion from the skyline view. This prominence is sometimes called a “razorback spine.” The disc spaces are narrowed on the concave side and widened on the convex side. There is distortion of the vertebral body, and vital capacity is considerably lowered if the lateral curvature exceeds 60°; compression and malposition of the organs within the rib cage also occur. Examples of scoliotic curves are shown in Figure 15-21.

Patient History

As with any history, the examiner must ensure that the information obtained is as complete as possible. By listening to the patient, the examiner can often comprehend the problem. The information should include a history of the problem, the patient’s general condition and health, and family history. If a child is being examined, the examiner must also obtain prenatal and postnatal histories, including the health of or injuries experienced by the mother during pregnancy, any complications during pregnancy or delivery, and drugs taken by the mother during that period, especially during the first trimester, which is the period when most of the congenital anomalies develop.

It should be remembered that it is unusual for a patient to present with just a postural problem. It is the symptoms produced by the pathology that is causing the postural abnormality that initiate the consultation. The examiner therefore must be cognizant of various underlying pathological conditions when assessing posture.

The following questions should be asked:

3. Are there any postures (e.g., standing with one foot on low stool, sitting with legs crossed) that give the patient relief or increase the patient’s symptoms?25 The examiner can later test these postures to help determine the problem.

5. Has the patient had any previous illnesses, surgery, or severe injuries?

7. Does footwear make a difference to the patient’s posture or symptoms? For example, high-heeled shoes often lead to excessive lordosis.26

12. If a deformity is present, is it progressive or stationary?

14. What is the nature, extent, type, and duration of the pain?

15. What positions or activities increase the pain or discomfort?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree