Chapter 140 Zingiber officinale (Ginger)

Zingiber officinale (family: Zingiberaceae)

General Description

General Description

The knotted and branched rhizome, commonly called the root, is the portion of ginger used for culinary and medicinal purposes. Extracts and the oleoresin are produced from dried unpeeled ginger, because peeled ginger loses much of its essential oil content.1,2 Ginger oil is produced from the fresh ginger via steam distillation.

Chemical Composition

Chemical Composition

The following compounds have been isolated from ginger:1,2

• Lipids (6% to 8%) composed of triglycerides, phosphatidic acid, lecithins, and free fatty acids

• Volatile oils (1% to 3%), the principal components of which are sesquiterpenes (bisabolene, zingiberene, and zingiberol) and various “pungent” principles, aromatic ketones, known collectively as gingerols vitamins (especially niacin and vitamin A)

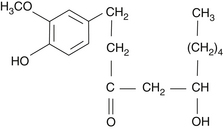

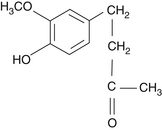

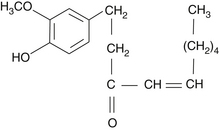

The pungent principles are thought to be the most pharmacologically active components of ginger. Gingerol and its derivatives can be found in concentrations as high as 33% in ginger oleoresin (Figure 140-1). The fresh oleoresin will have a higher percentage of the more pungent gingerol, because gingerol can be dehydrated during storage to form shogaol or have its fatty acid moiety cleaved to form zingerone (Figures 140-2 and 140-3). The oleoresin is made by extracting the oily and resinous materials with the aid of a solvent (alcohol, hexane, or acetone). Pharmacokinetic studies in humans show that the major pungent principles are absorbed after oral dosing and can be detected as glucuronide and sulfate conjugates in the blood.3

History and Folk Use

History and Folk Use

Ginger has been used for thousands of years in China for medicinal purposes. Chinese records dating from the fourth century B.C. indicate that it was used to treat the following conditions1:

It was used by eclectic physicians in the United States in the late 1800s as a carminative, diaphoretic, appetite stimulant, and local counterirritant.4

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

Ginger possesses numerous pharmacologic properties; the following are the most relevant:

• Inhibition of prostaglandin, thromboxane, and leukotriene synthesis

• Inhibition of platelet aggregation

• Cholesterol-lowering actions

Antioxidant Effects

Ginger has shown antioxidant effects in experimental studies.5 In a study in rats, ginger significantly lowered lipid peroxidation by maintaining the activities of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase. The blood glutathione content was significantly increased in ginger-fed rats. To achieve a similar effect with vitamin C, the dosage required was 100 mg/kg body weight.6

Ginger’s strong antioxidant properties have led to its being investigated for preventing the development of rancidity in meat products.7 Ginger has been shown to prolong the shelf life of fresh, frozen, and precooked pork patties. Because the use of many synthetic antioxidants is prohibited by law, ginger may one day be used commercially to extend the shelf lives of meats and other foods.

Effects on Prostaglandin and Leukotriene Metabolism

Numerous constituents in ginger have been shown to be potent inhibitors of prostaglandin and leukotriene synthesis through blocking of the cyclooxygenase enzymes.8–13 The most potent components appear to be the pungent principles, although the aqueous extract has also demonstrated inhibition. Inhibition of prostaglandin and leukotriene formation could explain some of ginger’s historic use as an antiinflammatory agent. However, ginger and its extracts also have strong antioxidant activities, and fresh ginger contains a protease with action that may be similar to that of other plant proteases (e.g., bromelain, ficin, papain) on inflammation.1 Repeated ginger administration to mice augmented corticosteroid secretion, indicating that chronic ingestion may produce an antiinflammatory effect via this mechanism as well.14

Effects on Platelets and Fibrinolysis

Ginger, like garlic and onions, is an inhibitor of platelet aggregation.11 However, ginger’s effects may be far more powerful. In a comparison, an aqueous extract of ginger was shown to exert greater inhibitory effects on platelet aggregation than aqueous garlic and onion extracts.15 Ginger was shown to produce a greater inhibition on thromboxane formation and proaggregatory prostaglandins. Ginger but not onion or garlic also significantly reduced platelet lipid peroxide formation. In another model, gingerol compounds and their derivatives were more potent antiplatelet agents than aspirin.11

The superiority of ginger over onions was also demonstrated in a controlled study.16 Female volunteers given either 70 g raw onion or 5 g raw ginger demonstrated that ginger has a pronounced effect in lowering platelet thromboxane production, whereas onion actually produced a mild elevation (pooled results).

In addition to acting on platelets, ginger promotes fibrinolysis. In one study, administration of 50 g of fat to 30 healthy adult volunteers decreased fibrinolytic activity from a mean of 64.20 to 52.10 U.17 Supplementation of 5 g of ginger powder with the fatty meal not only prevented the drop in fibrinolytic activity but actually increased the activity significantly.

Cholesterol-Lowering and Hepatic Effects

Ginger has been shown to significantly reduce serum and hepatic cholesterol levels in cholesterol-fed rats by impairing cholesterol absorption as well as stimulating cholesterol-7-alpha-hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme of bile acid synthesis.18–20 In addition, ginger has been shown to increase bile secretion.21 Therefore, ginger works to lower cholesterol by promoting excretion and impairing absorption.

Cardiotonic and Hypotensive Properties

Gingerol has shown potent cardiotonic activity (positive inotropic and chronotropic effects) on isolated guinea pig left atria.22,23 These effects are a result of acceleration of calcium uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Gingerol was the first substance shown to produce these effects.

Individuals with heart problems or high blood pressure are probably better off using fresh ginger rather than a dried preparation. This recommendation is based not only on the fact that gingerol is the more potent cardiotonic but also on the demonstration that shogaol has a blood pressure–elevating effect in animals.24 Gingerol is found predominantly in fresh ginger, whereas shogaol is rarely found in dried ginger.

Analgesic Effects

Ginger has demonstrated analgesic effects in experimental studies in animals.25 This effect is thought to be a result of inhibition by shogaol of the release of substance P, much like that by capsaicin, the pungent principle of red pepper (Capsicum frutescens).

Gastrointestinal Smooth Muscle Effects

Another aspect of ginger is its ability to simultaneously improve gastric motility and exert antispasmodic effects. This action is consistent with its use as a gastrointestinal tonic. A lipophilic ginger extract was shown in one study to enhance gastric motility, as evidenced by increased intestinal transport of a charcoal meal fed to rats,26 and various fat-soluble components of ginger, such as galanolactone, demonstrated antagonism of serotonin receptor sites.27 This latter mechanism may be responsible for ginger’s antispasmodic effects on visceral and vascular smooth muscle.

In a human study, 1000 mg of dried ginger did not affect lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure at rest or esophageal contractile amplitude and duration when swallowing, but caused more relaxation of the LES (after 90, 150, and 180 minutes, when swallowing) and decreased the esophageal contraction velocity, which may produce the expulsion of gastric gas or have an antiflatulant effect.28 Ginger has also been shown to inhibit serotonin-induced diarrhea and exert antiemetic effects in experimental models.29,30

Via inhibition of prostaglandin production, ginger also prevents the slow-wave dysrhythmias produced by acute gastrointestinal hyperglycemia.31

Ginger accelerates gastric emptying and stimulates antral contractions in healthy volunteers.32 Oral ginger extract was also shown to improve gastroduodenal motility in the fasting state and after a standard test meal in healthy human volunteers.33

Antiulcer Effects

Ginger has demonstrated significant antiulcer effects in a variety of animal models.34–36 Ginger prevents ulcer formation due to ethanol, indomethacin, aspirin, and other common ulcerogenic compounds. The pungent principles appear to be responsible for this effect. In one study, roasted ginger inhibited ulcer formation in three gastric ulcer models, but dry ginger had no such effect.37

A methanol extract of the dried powdered ginger rhizome, fractions of the extract, and the isolated constituents, gingerol and shogaol were tested against 19 strains of Helicobacter pylori—a bacterium associated with peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. The methanol extract of ginger rhizome inhibited the growth of all 19 strains in vitro with a minimum inhibitory concentration range of 6.25 to 50 mg/mL. One fraction of the crude extract, containing the gingerols, was active and inhibited the growth of all strains with a minimum inhibitory concentration range of 0.78 to 12.5 µg/mL.38

Thermogenic Properties

Ginger is noted for its apparent ability to subjectively warm the body and has historically been used as a diaphoretic. In animal studies, ginger has been shown to help maintain body temperature and to inhibit serotonin-induced hypothermia.29,39

Crude extracts and the pungent components of ginger have been shown to increase oxygen consumption, perfusion pressure, and lactate production in the perfused rat hind limb.40 These effects signify increased thermogenesis. Gingerol is the most potent thermogenic component of ginger. A human study demonstrated that consuming a ginger sauce (containing unspecified amounts of ginger principles) with a meal had no significant effect on metabolic rate.41 However, there were two problems with this study: (1) the concentration of gingerol in the preparation used was probably low or zero and (2) the effective concentration range of gingerol for its thermogenic effects is quite narrow.

Antibiotic Activity

Ginger, shogaol, and zingerone have been shown to be strongly inhibitory against Salmonella typhi, Vibrio cholerae, and Trichophyton violaceum, whereas aqueous extracts at 2.5%, 5%, and 25% concentrations have been shown to be effective against Trichomonas vaginalis.42 Ginger and its pungent principles were also demonstrated to possess significant antifungal activity against pathogenic yeast.43

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree