Chapter 8 Yoga

Initial Examination

Initial Examination

Employment: Client is a graduate student with no outside employment.

Recreational Activities: Strength training, skiing, hiking, camping

Outcome Measurements: SF 36=30 (below the standard norm); Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire (ODI) Score=38%, which indicates moderate disability.1,2 Life Stress Inventory=225 implies about a 50% chance of a major health challenge in the next 2 years.3 The use of these measures guides the therapist in Harrison’s perceived stress and disability as it relates to plans for intervention.

INVESTIGATING THE LITERATURE

The therapist uses two strategies to investigate the literature. The first is a detailed approach in which preliminary background reading is performed on the management of LBP and CTS with yoga. This is followed by a search of databases and evaluation of the evidence with use of reviews and primary sources for LBP and CTS and yoga. The second is the use of the PICO format for a focused search to answer the clinical questions generated by the case. In this case two PICOs are generated to address CTS and LBP separately.

Preliminary Reading: Yoga

This client is not alone in his quest to explore yoga as a potential therapy. Millions of people in the United States, whether by their own curiosity or by the recommendation of their doctors, physical therapists, and others, are exploring yoga as a therapy for a broad spectrum of medical conditions.4 In fact, a recent survey of the use of CAM in American adults demonstrated that of those who used yoga specifically as a CAM therapy, 21% did so because it was recommended by a conventional medical professional, 31% did so because conventional therapies would not help, and 59% thought it would be an interesting therapy to explore.5 For centuries yoga has been practiced as a therapeutic modality in traditional Indian medicine.4 Yoga is now one of the most common mind-body therapies used in Western complementary medicine.6 It uniquely brings about physical and mental benefits and involves inexpensive self-care–based activities, which makes yoga appealing as a cost-effective alternative to conventional treatments.7,8 Yoga therapy is an emerging field and is the first attempt to integrate the traditional yogic practice with Western medicine.9 Before they recommend yoga therapeutically, therapists first must understand the traditional practice of yoga.

Overview of Yoga

Yoga is complex. Its long and rich history extends back 5000 years to ancient India. Therefore to explore the totality of yoga within this chapter is impossible. Additional resources are provided at the end of this chapter in Appendix 1 for further exploration of yoga’s history, philosophy, and practice. More information on yoga can be found in Chapter 7.

Yoga, in the traditional sense, is a spiritual way of life that extends well beyond the complicated poses and breath work. The traditional practice of yoga is actually a rigorous spiritual discipline composed of a vast array of physical and mental exercises, in addition to philosophical, moral, and even nutritional practices, all aimed at self-transformation by union of the mind, body, and spirit. As such, yoga truly embodies a holistic approach to life and health. It takes even the most dedicated a lifetime to master. For the most part, however, since its introduction to the West in the late 1880s, yoga has undergone a metamorphosis into a more physically based “fitness yoga.” Many purists, however, still see this Westernized yoga form as an opportunity for exploring the deeper side of yoga and the spiritual aspects of life.9

Yoga is complex even to define. The word yoga has several translations and comes from the root “yug” (to join), or “yoke” (to bind together). Essentially, yoga describes a method of discipline or means of uniting the body to the mind. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) classifies yoga as a mind-body therapy, defining it as “yoga—this combination of breathing exercises, physical postures, and meditation, practiced for over 5000 years, calms the nervous system and balances body, mind, and spirit. It is thought to prevent specific diseases and maladies by keeping the energy meridians open and life energy flowing.”5 Yoga, like other mind-body therapies, is centered on development and/or enhancement of physical, psychological, and spiritual health.10 Yoga’s belief system that strongly claims mind, body, and spirit are interwoven is manifested and realized through the dedicated practice of yoga.9

Yoga Practice

What is commonly referred to as “yoga” in the West is actually Hatha yoga, one of dozens of types of Hindu yoga practiced around the world today. Hatha yoga is the “yoga of activity,” with a higher focus on physical postures, deep breathing exercises, and meditation in contrast to other forms of yoga, which may focus more on ethics, meditation, or diet. Because it is one of the types of yoga one can experience, its tangibility has made it the most popular form of yoga practiced in the West and the most practical therapeutically. All styles of yoga, however, are said to lead down the same path, that being toward spiritual enlightenment through self-transformation.9

The traditional path of Hatha yoga is said to involve eight components, or limbs, to attain a person’s full potential and live a purposeful life.9 These components are a prescription for self-discipline, and they direct attention towards one’s body, mind, and overall health. These eight paths include (1) moral precepts, (2) personal behavior concepts, (3) physical postures (most familiar to Westerners), (4) conscious regulation of the breath, (5) focus of the senses inward, (6) concentration, (7) meditation, and (8) ecstasy. Each path is meant to lead to the next. Although to mention these paths of the traditional Hatha practice is important, the focus for this client should center on the more physical and mental aspects for which Hatha yoga is known and that the client would most likely encounter. Several elements in Hatha yoga exist, which include physical postures (asanas), breathwork (pranayama), withdrawal (pratayahara), concentration (dharana), and meditation (dhyana).

The physical postures, called asanas, are designed to purify, cleanse, and gain mastery over the physical body to allow the body to prepare for meditation or stillness.11 In the yogic view, a strong, flexible, and conditioned body is necessary as a foundation for the higher spiritual pursuits. Although not typically considered an aerobic exercise, these yogic postures are meant to help the client develop strength, flexibility, and endurance in muscles and improve circulation and alignment in spine.9

More than 200 actual asanas exist, each with its own purpose, which creates a system designed to seek out every muscle, joint, and ligament and exercise it.9 Within a pose, certain muscles are meant to be flexed, others stretched, which enables relaxation and improved flexibility. Procedures exist for entering, holding, and emerging from each pose, along with specific sequences of poses. Movements are typically slow and coordinated with controlled breathing so that full inhalation is achieved upon entering the pose. The pose and breath are held briefly and then released simultaneously so that the starting point is reached at full exhalation. Every pose has a counterpose to balance its effects.

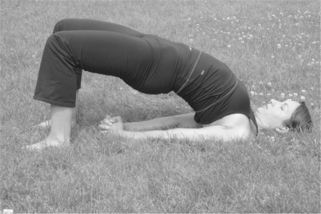

Typically every practice uses a variety of poses; most involve the muscles of the back and abdomen (Figure 8-1). Standing poses are designed for centering and alignment (Figure 8-2). Seated poses are designed to be more calming than the standing poses (Figure 8-3). Forward bends, with flexion in the hips, rather than the spine, can be done seated, standing (Figure 8-4), supine, twisting, balancing, or inverted. Balancing postures are designed to develop the body’s coordination and strength (see Figure 8-2). Twisting poses help activate the spine, internal organs, and muscles (Figure 8-5). Backbends are meant to strengthen the extensor muscles, stretch the flexor muscles, and stimulate the entire nervous system (Figure 8-6). Inversion postures are said to strengthen the cardiovascular system and obviously reverse the effects of gravity (see Figure 8-4).

Figure 8-3 Seated pose for meditation and stillness: lotus. Reproduced with permission of Joel Stern.

Many various styles of Hatha yoga exist, each approaching the asana practice in a particular way (Table 8-1). Some use faster, flowing asana movements, such as Ashtanga, whereas others, such as Iyengar, use poses held for longer durations with attention to detail. Iyengar is one of the most popular styles in the West and uses props to accommodate special needs of the yoga instructor Viniyoga is another popular form, which allows poses to be customized to the individual; thus it is good for students with physical limitations.

Table 8-1 Different Schools of Hatha Yoga Commonly Practiced in the United States

| SCHOOL | FOCUS | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| Iyengar | Detail | Technical yoga, an intense focus on the subtleties of each posture; great for beginning students |

| Strong focus on precise muscular and skeletal alignment; emphasizes therapeutic properties of the poses | ||

| Poses (especially standing postures) are typically held much longer than in other schools of yoga to focus on alignment | ||

| Use of props (belts, chairs, blocks, and blankets) to accommodate special needs such as injuries or structural imbalances. | ||

| Ashtanga/Power Yoga | Fitness | Athletic; fast paced and non-stop; not recommended for beginning students |

| At the core is linking the breath with each movement thoughout the practice | ||

| Power Yoga is a derivative, using a more creative sequences of postures | ||

| Jivamukti | Fitness | Athletic; highly meditative but physically challenging form of yoga |

| Combines an Ashtanga background with a variety of ancient and modern spiritual teachings | ||

| Uses chanting, meditation, reading, music, and affirmations | ||

| Bikram/Hot Yoga | Healing | Athletic; practiced in a room heated to 100+ degrees, thus “hot” yoga |

| Sauna-like effect helps move the toxins out of your body | ||

| Kripalu | Healing | Therapeutic; gentle and spiritually focused; Great for beginning students |

| Incorporates inner focus and meditation within the yoga poses; focus on alignment, breath, and the presence of consciousness | ||

| Holding of the postures to the level of tolerance and beyond | ||

| Deepens concentration and focus of internal thoughts and emotions | ||

| Integrative Yoga Therapy | Healing | Designed specifically for medical and mainstream wellness settings including hospitals and rehabilitation centers |

| Gentle postures, guided imagery, and breathing techniques for treating specific health issues | ||

| Emphasizes the healing process in detail by addressing all levels of the patient: physical, emotional, and spiritual | ||

| Phoenix Rising Yoga Therapy | Healing | Combination of classical yoga and elements of contemporary client-centered and mind-body psychology |

| Facilitates a power release of physical tensions and emotional blocks | ||

| Assisted yoga postures, guided breathing, and nondirective dialogue | ||

| Focused on experiencing the connection of the physical and emotional self | ||

| Viniyoga | Healing | Therapeutic; repetitious movements in and out of a posture |

| Individualistic; poses are synchronized with the breath in sequences determined by the needs of the practitioner | ||

| Highly adaptable, thus good for students with physical injuries or limitations | ||

| Svaroopa | Healing | Consciousness-oriented, emphasizing the development of transcendent inner experience, called svaroopa |

| Promotes healing and transformation; teaches different ways of doing familiar poses | ||

| Emphasizes the opening of the spine by beginning at the tailbone and progressing through each spinal area | ||

| Ananda | Enlightenment | Tool for spiritual growth while releasing unwanted tensions |

| Uses silent affirmations while holding a pose as a technique for aligning body, energy, and mind | ||

| Series of gentle poses designed to move energy upward to the brain, preparing the body for meditation. | ||

| Integral | Enlightenment | Aimed at helping people integrate yoga’s teachings into their everyday work and relationships |

| Incorporates guided relaxation, breathing practices, sound vibration (repetition of mantra or chant), and silent meditation | ||

| Kundalini | Enlightenment | Dynamic; esoteric; energizing; aimed at invoking dormant spiritual energy at the base of the spine |

| Incorporates breath-work, movement, postures, chanting, and meditating on mantras. | ||

| Sivananda | Enlightenment | Traditional approach; can become very advanced |

| Ridgid class structure of poses, breath-work, mediation, and relaxation. | ||

| Emphasizes 12 basic postures to increase strength and flexibility of the spine | ||

| Focus on proper pose, breathing, relaxation, and diet (vegetarian), and positive thinking and meditation |

Generally associated with the asanas is breath control, a practice called “pranayama,” which also can be used as an isolated practice. The pranayamic breath is meant to be deep, rhythmic breathing through the nose during inhalation and exhalation. Pranayama is designed to gain conscious control of one of the most basic and largely unconscious bodily functions and allows realization of the connection between the breath, mind, and emotions.9 In the yogic view, if the breath is calm and controlled, so can be the mind.4

Two other limbs of the yogic practice, pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses) and dharana (concentration), are important skills that increase attention and awareness. Practicing these two paths is said to place a person in “the zone” and helps bring awareness to positioning and posture. These are also important practices that allow people to sense and understand the limitations of their bodies.9 These practices allow someone to draw attention inward, learn to recognize habitual thought patterns, and become aware of the body and its rhythms. The practice of meditation, or dhyana, results in uninterrupted concentration aimed at quieting the mind and body. It commonly is used as a practice apart from the other yogic practices.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Plan of Care

Plan of Care Reevaluation

Reevaluation Incorporating CAM into the Plan of Care

Incorporating CAM into the Plan of Care