Wound management

Richard Mowrer

Introduction

The integument (the skin) is a vital organ. When a person sustains an injury to the integument, a break has occurred in the protective barrier between the organs/underlying tissues and the outside environment. This principle is crucial to the survival of the older adults especially, because chronic dermal wounds occur frequently in the elderly (Zhao et al., 2010). The body’s ability to heal is altered by various health problems – diabetes mellitus, circulatory problems, hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Normal age-related changes in skin also affect the rate and quality of healing (see Chapter 50), and there may be additional risk factors including inadequate nutrition, limited mobility and muscle atrophy.

Wounds and the healing process

The normal healing process has three phases (Stillman, 2005). In phase one the inflammatory response is activated, which is the body’s natural response to injury. This inflammatory response extends from injury to 4–6 days after injury. The process follows a normal sequence of events, including vasoconstriction, fibrin clots, vasodilatation and the presence of neutrophils and macrophages that remove bacteria and debris. Initially after injury, transudate leaks out of the blood vessels to fill the interstitial space, leading to localized edema and, thus, slowing the bleeding. Next, blood vessels reflexively constrict to assist with reducing blood loss. Platelets aggregate and become ‘sticky’; this plugs up the lymphatic tissue, causing greater edema. The platelets release growth factors that control cell growth, differentiation and metabolism. Finally, chemotactic agents are released to attract cells that are necessary to fight infection and repair the wound. As the chemotactic agents attract new healing cells, the vasoconstriction changes to vasodilatation, allowing these cells to reach the site of the injury. Vasodilatation results in localized redness, swelling and warmth, which are characteristics of inflammation. Fluid seeping from the wound, containing macrophages, white blood cells (WBC) and neutrophils, is called exudate; it is yellow/cream colored and more viscous than transudate. Pain is also usually present (Mowrer, 2004).

Phase two, the proliferative phase, occurs approximately 7 days after injury. This phase includes the utilization of growth factors, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, new blood vessels and collagen. The growth factors also generate keratinocytes, which are involved in re-epithelialization. The inflammatory and proliferation phases usually overlap, with no definitive marker for when one ends and the other begins. There are four crucial events of the proliferative stage:

In phase three, the remodeling phase, there is no longer an open wound. During this phase, connective tissue becomes better aligned and tensile strength increases. After the re-epithelialization process has completely covered the wound surface, the maturation phase begins; this means the ‘new skin’ begins to thicken and mature. The new skin is primarily scar tissue that is formed by randomly laid down collagen. This collagen will eventually need to be ‘remodeled’ so that it can work in conjunction with the surrounding tissue, i.e. move or become mobile. This process can take up to 2 years to complete (Stadelmann et al., 1998).

Wound classification

Wounds are generally classified according to the predominant underlying cause. Common categories include arterial insufficiency, venous insufficiency, pressure ulcers, neurotrophic ulcers, traumatic wounds and burns. There are several wound classification systems. Table 48.1 presents the classification systems for pressure ulcers (NPUAP, 2007) burns, and venous, arterial and traumatic wounds that are not included in the other classifications. The Wagner (1981) system is another important assessment tool for the classification of ulcer stages (Table 48.2).

Table 48.1

| Wound Type | Classification | Characteristics |

| Pressure ulcers | Stage I | Nonblanchable erythema of intact skin, the heralding lesion of skin ulceration |

| Stage II | Partial-thickness skin loss involving epidermis and/or dermis; ulcer is superficial and presents clinically as an abrasion, blister or hollow crater | |

| Stage III | Full-thickness skin loss involving damage or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that may extend down to, but not through, underlying fascia; ulcer presents clinically as a deep crater, with or without undermining of the adjacent tissue | |

| Stage IV | Full-thickness skin loss with extensive destruction, tissue necrosis or damage to muscle, bone or supporting structures (e.g. tendon or joint capsule) | |

| Unstageable | Full-thickness loss in which actual depth is completely obscured by slough and/or eschar | |

| Suspected deep tissue injury – depth unknown | Purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear | |

| Burns | First-degree | Involves the superficial epidermal layer; skin is pink or red, dry and painful, and sheds within a week without residual scar |

| Second-degree | Involves the epidermis and the dermis; wound is immediately blistered and wet, local edema is present; if superficial, will heal within 2–3 weeks and will not scar if not infected or unduly traumatized; if deep, may require skin grafting to achieve optimal healing | |

| Third-degree | Involves the entire thickness of the skin; wound varies in color from white to black and may present with dark networks of thrombosed capillaries that do not blanch with pressure; surface is usually dry, but may be wet; these wounds require skin grafting for closure if more than 1 in (2.54 cm) in diameter | |

| Burns are also designated, at times, by partial- and full-thickness; first- and second-degree burns are synonymous with partial-thickness. Full-thickness burns are those in which the entire epidermis has been destroyed. Parts of the dermis may also be destroyed, along with injury into the subcutaneous structures | ||

| Venous, arterial, and traumatic wounds | Partial-thickness | Penetration into the epidermis or into the beginning of the dermis |

| Full-thickness | Penetration into the subcutaneous tissue, muscle or bone |

Table 48.2

Wagner classification system of ulcer stages

| Stage | Description |

| 0 | Intact skin |

| 1 | Superficial ulcer involving skin only |

| 2 | Deep ulcer involving muscle and, perhaps, bone and joint structures |

| 3 | Localized infection; may be abscess or osteomyelitis |

| 4 | Gangrene, limited to forefoot area |

| 5 | Gangrene of the majority of the foot |

Evaluating the patient

Evaluation of a patient with a wound should be completed by a multidisciplinary team (physician, nurse, physical therapist and social worker, and nutritionist). The physical therapist plays an important role and must have expertise in dealing with the integumentary system and the classification of wounds to establish a plan of care that optimizes wound homeostasis and healing. It is important to remember to treat the patient, not the wound.

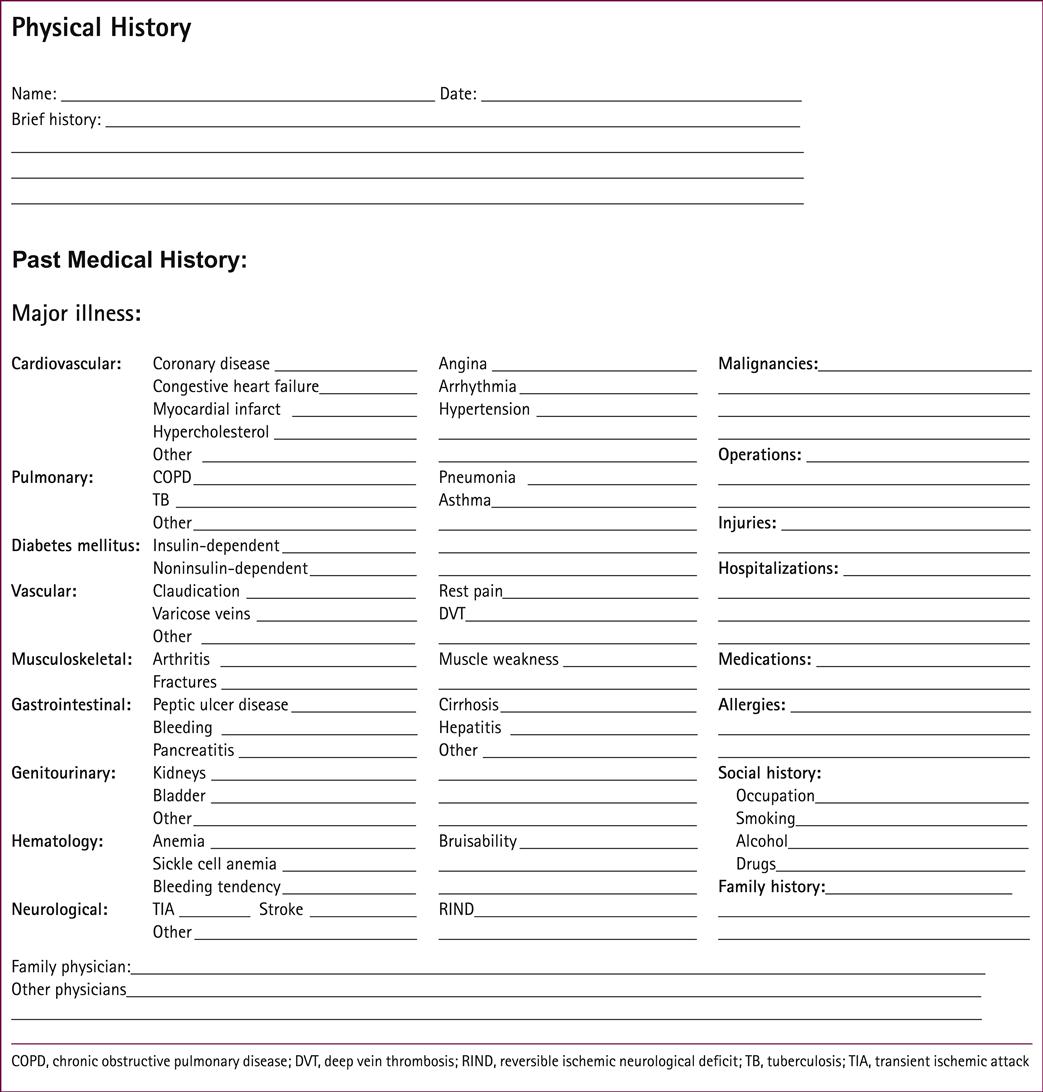

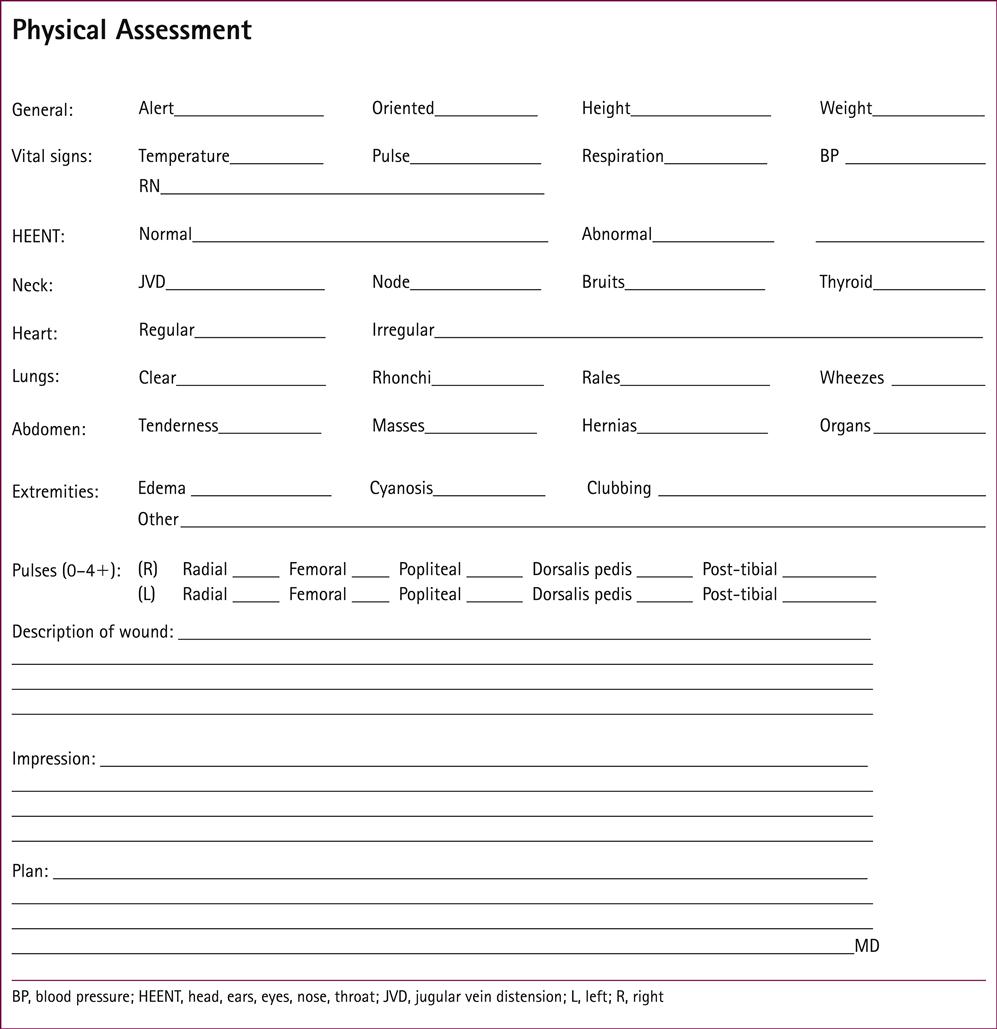

When initiating the evaluation, the following elements should be included (see Forms 48.1, 48.2 and 48.3):

• Assess the integument. Is it well hydrated? Is there good turgor?

• Assess nutrition. What and how much is the patient eating?

• Review the patient’s personal care (hygiene).

• Assess peripheral pulses, i.e. ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) (see Table 48.3).

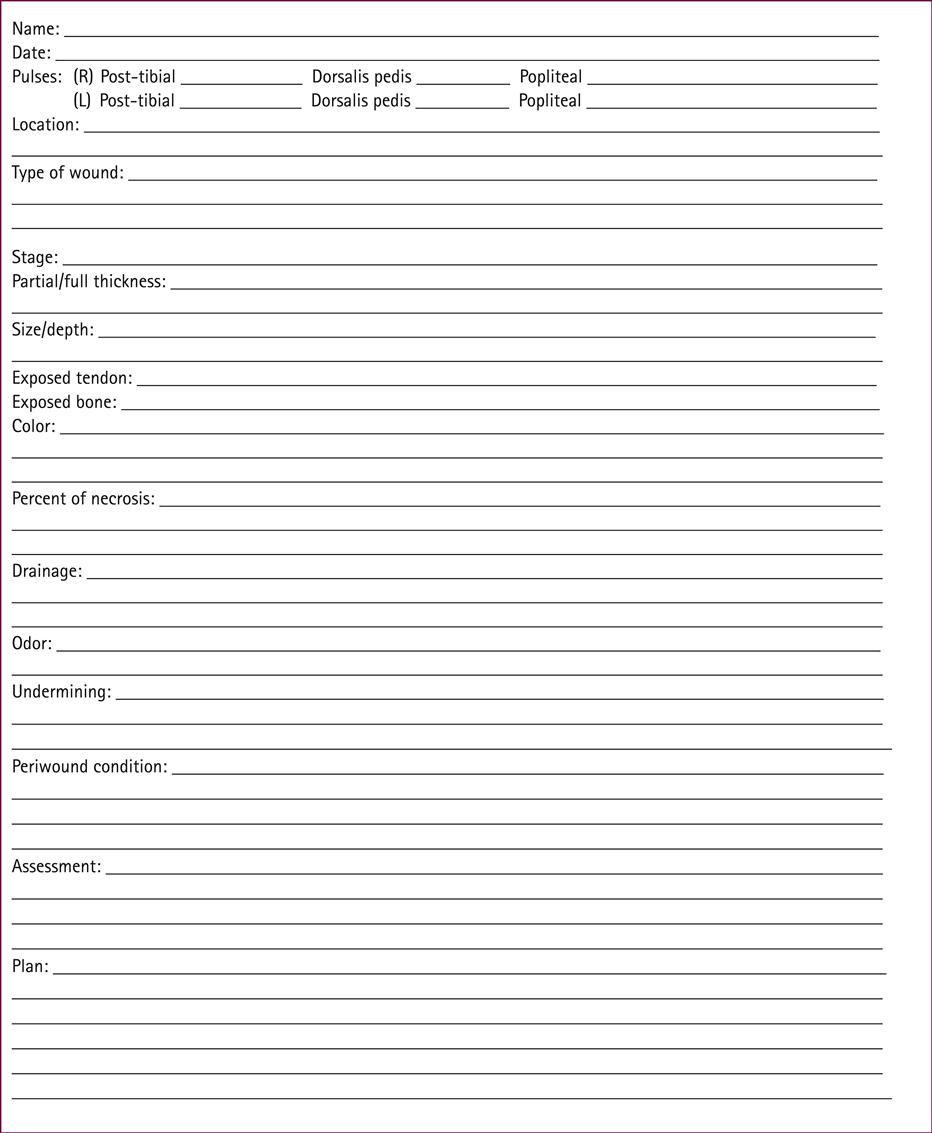

• specific location of the wound;

• size of the wound (length, width, depth);

• percentage of necrotic tissue, slough and granulation tissue;

• drainage (amount, odor, color, consistency);

• presence of undermining or tunneling;

Table 48.3

| ABPI | Interpretation | Possible Vascular Interventions |

| 1.1–1.3 | Vessel calcification | ABPI not valid measure of tissue perfusion |

| 0.9–1.1 | Normal | None needed |

| 0.7–0.9 | Mild to moderate insufficiency | Conservative interventions normally provide satisfactory wound healing |

| 0.5–0.7 | Moderate arterial insufficiency with intermittent claudication | May perform trial of with conservative care, physician may consider revascularization |

| <0.5 | Severe arterial insufficiency, rest pain | Wound is unlikely to heal without revascularization, limb-threatening arterial insufficiency |

| ≤0.3 | Rest pain and gangrene | Revascularization or amputation |

From Myers B 2004 Wound Management: Principles and Practice. Prentice Hall, Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River, NJ, p 211, with permission.

ABPI procedure

ABPI is measured using Doppler ultrasound, a hand-held device that utilizes sound waves to determine blood flow, and a blood pressure cuff. This is a quantitative way to measure blood flow without invasive testing. With the Doppler ultrasound, a whooshing sound is heard, either biphasic (two sounds) or monophasic (one sound). The ultrasound device should be held at a 45° angle to the artery, against the direction of flow (gel will need to be utilized). The blood pressure of the brachial artery is taken as ‘normal’ and the maximum cuff pressure at which the pulse can just be heard with the Doppler ultrasound is recorded. This is repeated on the lower extremity (usually the dorsalis pedis). The blood pressure of the lower extremity is divided by that of the upper extremity to give the ABPI. In the presence of diabetes mellitus, the arteries may be calcified, therefore the measurements will be altered and unreliable. If this is the case, an arteriogram is indicated. If Doppler ultrasound is not available, pulses will need to be assessed using palpatory skills or vascular studies.

Types of ulcers

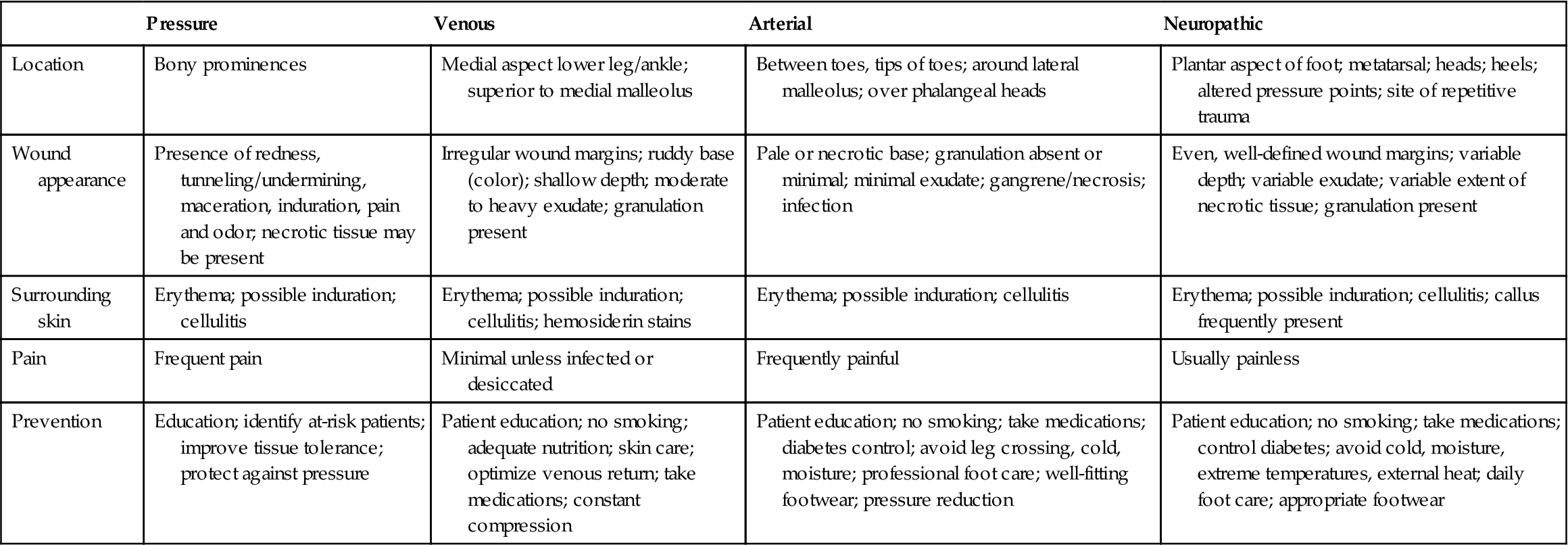

In order to intervene appropriately in the treatment of ulcers, it is crucial to be able to distinguish between the various different types (Table 48.4). (See Chapter 9, Effects of aging on vascular function.)

Table 48.4

| Pressure | Venous | Arterial | Neuropathic | |

| Location | Bony prominences | Medial aspect lower leg/ankle; superior to medial malleolus | Between toes, tips of toes; around lateral malleolus; over phalangeal heads | Plantar aspect of foot; metatarsal; heads; heels; altered pressure points; site of repetitive trauma |

| Wound appearance | Presence of redness, tunneling/undermining, maceration, induration, pain and odor; necrotic tissue may be present | Irregular wound margins; ruddy base (color); shallow depth; moderate to heavy exudate; granulation present | Pale or necrotic base; granulation absent or minimal; minimal exudate; gangrene/necrosis; infection | Even, well-defined wound margins; variable depth; variable exudate; variable extent of necrotic tissue; granulation present |

| Surrounding skin | Erythema; possible induration; cellulitis | Erythema; possible induration; cellulitis; hemosiderin stains | Erythema; possible induration; cellulitis | Erythema; possible induration; cellulitis; callus frequently present |

| Pain | Frequent pain | Minimal unless infected or desiccated | Frequently painful | Usually painless |

| Prevention | Education; identify at-risk patients; improve tissue tolerance; protect against pressure | Patient education; no smoking; adequate nutrition; skin care; optimize venous return; take medications; constant compression | Patient education; no smoking; take medications; diabetes control; avoid leg crossing, cold, moisture; professional foot care; well-fitting footwear; pressure reduction | Patient education; no smoking; take medications; control diabetes; avoid cold, moisture, extreme temperatures, external heat; daily foot care; appropriate footwear |

Venous

Venous insufficiency, defined as a disturbance in the forward flow of blood in the lower extremities, may progress to increased hydrostatic pressure, venous hypertension and, ultimately, dermal ulceration (Fig. 48.1). Signs and symptoms of venous disease are hemosiderin staining, a purple hue that covers the skin (Fig. 48.2), coupled with a ‘heavy feeling’ in the legs and edema. Venous wounds are usually found in the lower leg in the proximity of the medial malleoli. These wounds present with large surface areas and have shallow edges. Many patients will complain of increased pain with prolonged lower extremity dependence, such as standing or sitting, with relief upon elevation of the involved limb.

The wound bed will be wet with a mixture of viable and nonviable tissues. An ABPI of>0.8 will present in the venous wound, as will palpable pulses. Palpating pulses in the edematous lower extremity can be difficult. In this instance, it may be beneficial to seek a noninvasive vascular study through the patient’s referring physician or the medical director.

Patients with venous insufficiency are frequently significantly overweight. Therefore, it is important to include a weight loss program or consult a dietician for the comprehensive management of venous disease.

The etiology includes valvular incompetence of lower extremity veins, obstruction of the deep venous system, congenital absence or malformation of valves in the venous system and regurgitation from the deep to the superficial venous system via the venous perforators that connect the deep and superficial venous systems. Inadequate pulmonary function will augment the problem because of a weak ‘pulmonary pump’. The pulmonary pump functions via deep breathing, forcing the diaphragm against the abdominal cavity and increasing the pressure on the venous system, which increases the flow of blood. Additionally, the deep veins are surrounded by calf muscles that act as pumps by squeezing the veins and forcing the blood proximally. Paralysis or atrophy (possibly caused by a sedentary lifestyle) will impair this pump. This demonstrates the importance of exercise, specifically aerobic exercise, for patients with open wounds. Failure of the muscle pump is usually coupled with venous dysfunction, i.e. the veins fail to function and/or the one-way valves stop working. The veins become distended, with the increased internal pressure from the backflow of blood and subsequent increase in pressure in the capillaries leading to a ‘cuff-like’ pressure around the wound that limits oxygen and nutrients reaching the tissues. Proteins and fluids migrate out of the vein walls and flood the interstitial tissues, leading to edema and hemosiderin staining.

The treatment of venous insufficiency involves four major areas: (i) control of underlying medical and nutritional disorders; (ii) education of the patient; (iii) control of edema; and (iv) topical therapy to reduce bacterial load, control drainage and promote granulation tissue formation.

Arterial

Arterial insufficiency is defined as insufficient arterial perfusion of an extremity or particular location (Fig. 48.3). It may be caused by arteriosclerosis, trauma, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, Buerger’s disease or atherosclerosis. The ABPI will be>0.8, signifying arterial involvement. Any edema is localized or can be associated with an infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree