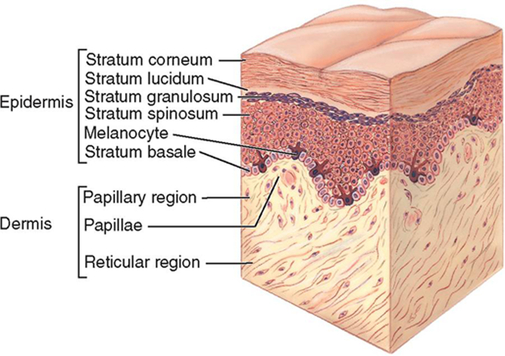

Both the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) and the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) definitively state that wound care is within the scope of practice of occupational therapists and physical therapists, respectively.1–2 Many state practice acts also define wound care as within our scope of practice, but states vary with regard to what specific wound care procedures can be performed by occupational and physical therapists. As such, you should always consult your state licensing board on the legal parameters of providing this service in your state. For the purposes of this text, we will consider a wound as any sort of open traumatic or surgical damage to the skin. The skin consists of two layers: the epidermis and the dermis (Figure 21-1). • Temperature of the wound bed • Amount of moisture in and around the wound • Medications and other medical conditions Adequate circulation is essential to wound healing. Wounds will not heal unless an adequate supply of oxygenated blood reaches the wound bed. Many things can reduce blood flow to the hands, such as peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, smoking,3 excessive edema, and mechanical stress from orthotics or dressings. It is the therapist’s responsibility to assure that all wound dressings and orthotics fit correctly. Dressings that are wrapped too tightly or orthotics that cause pressure areas can affect circulation in the hand. Chemical stress occurs when a toxic substance makes contact with granulation tissue forming in the wound bed. Cells that make up granulation tissue are very fragile and must be treated with care. When chemical stress occurs, the new cells die, and this slows the rate of wound healing. Many products that have traditionally been used to clean wounds, such as hydrogen peroxide and povidone-iodine, are cytotoxic and can kill tissue cells.4 You must use care in choosing wound cleansing products, and educate your clients to do the same. The temperature of the wound bed also influences healing. Wounds heal best when the wound surface temperature is kept relatively constant and close to the normal core body temperature range of 36° C to 38° C (96.8° F to 100.4° F).5 The temperature of the wound bed drops, on average, 2 degrees Celsius (3.6° F) when the dressings are removed and the wound is cleansed with room temperature saline. It can take up to 3 hours for the temperature of a wound to return to pre-dressing change temperature once a new dressing is applied.6 Strategies that reduce the frequency of dressing changes help keep the wound warm and the temperature more constant, and this assists with healing. Another factor that assists with wound healing is moisture balance. A wound that is either too wet or too dry will not heal as quickly as a properly-balanced moist wound. A moist wound provides the optimal environment for cell growth and migration of epithelial cells over the wound bed. Wounds with a high level of exudate (drainage) can become too wet, and this often leads to breakdown of the wound bed and surrounding skin. Wounds with little or no exudate can become too dry, and this slows the action of regenerative cells in the wound.7 Finally, there are a few factors specific to the uniqueness of each client that will interact and affect wound healing. Wounds in younger clients tend to heal more quickly than wounds in older clients. This is generally due to the presence of medical conditions, medications, and inadequate nutritional intake more likely to be found in older clients. However, when these factors are present in younger clients, the effect on wound healing is the same. Chronic diseases, such as peripheral vascular disease and diabetes, will slow wound healing. Clients with cancer or AIDS or those with autoimmune disorders who require immunosuppressive drug therapy will also demonstrate slower wound healing.8 Additionally, clients with chronically poor nutritional intake will demonstrate less efficient wound healing because malnutrition affects cell production, collagen synthesis, and wound contraction.9 There is one more thing to mention about preparing the wound for healing through the removal of unwanted tissue. A healthy wound bed is pink-red. However, there is a certain type of tissue that forms in the wound bed that is red-colored but undesirable. This tissue develops when there is an overgrowth of granulation tissue, possibly due to infection or excessive moisture in the wound.10 It is called hypergranulation tissue. Hypergranulation tissue normally looks like shiny, deep-red balls of tissue that grow taller than the wound margins. Some therapists think it looks like little red raspberries (Figure 21-5). The tissue is soft and will often bleed easily when touched. This tissue must be treated in order for the wound to heal normally. An effective way to treat this tissue is to apply silver nitrate to the hypergranular areas.10,11 Use silver nitrate sticks and roll the treatment end of the stick over the abnormal tissue. As you treat the tissue, it will turn gray in color. After treating with silver nitrate, you can bandage the wound as you normally would. Repeat the procedure at each dressing change until the hypergranulation tissue is controlled. The best solutions for cleansing wounds in the hand clinic include normal saline, sterile water, and drinkable tap water.12 Avoid using solutions such as hydrogen peroxide, Dakin’s solution, povidone iodine/Betadine, soap, or bleach on clean wounds. These solutions contain chemicals that are toxic to granulation tissue, and use of these solutions will slow wound healing. Using a product like hydrogen peroxide is really only appropriate in the home setting for cleaning cuts and scrapes immediately after an injury. Hydrogen peroxide is fine for cleaning a dirty superficial wound at home once or twice. However, once that wound is free of injury-related debris like dirt, asphalt, and grass, it should be cleansed with saline, sterile water, or drinkable tap water so as not to impede the healing process. The method you use to apply the cleansing solution is also important. You want to use enough pressure to remove surface debris and contaminants without causing trauma to any new tissue forming in the wound bed. To date, research has failed to identify the ideal method of wound cleansing.13 However, most practitioners have discarded the practice of whirlpool wound cleansing and replaced that method with syringe irrigation. Syringe irrigation is more convenient and carries less risk of cross-contamination between clients than whirlpool cleansing. Much of the available literature indicates that wounds seen by the hand therapist should be irrigated with pressures at or below 8 psi.13,14 A 35 mL medical syringe with a 25-gauge needle will produce 4 psi, and a 35 mL/19 gauge combination will produce 8 psi.15 This equipment is readily available in most health care settings. You can cleanse all wounds in the clinic with either of these syringe/needle combinations filled with saline, sterile water, or drinkable tap water. When occlusive dressings first arrived on the scene, many physicians feared that their use would cause infection. This myth is still prevalent in some settings. However, research has shown that occlusive dressings do not increase the risk for infection.17 The goal is to find a dressing that will keep bacteria out, retain some moisture, but still absorb any excess fluid if needed. Standard dressing choices generally fall into the following categories: transparent films, impregnated low-adherence dressings, hydrogels, hydrocolloids, gauze, foams, and alginates. There are other types of specialty dressings available, but the typical hand therapist will make his or her selection from these standard dressing choices. Every medical supply company has these types of dressings available, but they will be identified by different brand names. When looking for a specific type of dressing, ask your supplier for the names of the available dressings in that category. The dressing categories described below are listed in order from least absorptive to most absorptive.18–21 These versatile dressings are exactly what they sound like: thin, see-through films (Figure 21-2). Films come in a variety of shapes and sizes and easily conform to the contours of the hand. They adhere right to the skin and can be used either as a primary dressing (making contact with the wound) or as a secondary dressing (holding a primary dressing in place). Transparent films are semi-occlusive in that they are permeable to water vapor, but impervious to liquids and bacteria.19 Therefore, they are waterproof in the shower and good at keeping bacteria out of the wound. Another advantage of transparent film dressings is our ability to see the wound without removing the film. Films are non-absorptive, and because these dressings hold most moisture in, they are excellent for promoting autolytic debridement of slough or moist eschar. Transparent films must be changed if too much fluid builds up under the film and starts to leak out the edges. However, dry or very low draining wounds can tolerate a film dressing in place for up to 7 days.

Wound Care

Introduction

Diagnosis

Timelines and Healing

Normal Wound Healing

Factors Affecting Wound Healing

Non-Operative Treatment: Basic Wound Management

Wound Debridement

Wound Cleansing

Maintenance of Moisture Balance

Transparent Films

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Wound Care