Chapter 4 Whole Medical Systems

Traditional or whole medical systems are defined by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) as those that “involve complete systems of theory and practice that have evolved independently from or parallel to allopathic (conventional) medicine.”1 They are practiced by individual cultures throughout the world. Examples of whole medical systems include Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) from the East, and homeopathy and naturopathy from the West. Other systems have been developed by Native American, African, Middle Eastern, Tibetan, and Central and South American cultures.1 Because entire books are dedicated to the description and evaluation of each of the whole medical frameworks, in this chapter the coverage of these systems is brief. Introductions to selected whole medical systems, specifically, Ayurveda, TCM, Native American medicine, and naturopathy, are presented here. These whole medical systems were selected to introduce the reader to ancient classical systems in contrast with a more modern system, such as naturopathy. Selecting four systems allows the novice reader to appreciate commonalities and differences between the rationale and approaches of whole medical systems and to contrast the evidence base for each system. Further, Ayurveda and TCM serve as the basis for many individual therapies used in rehabilitation (such as yoga and tai chi) and are reported among the most frequently used therapies in the United States.2 Homeopathy is covered in some detail in Chapter 6. Two excellent complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) books that cover all of the topics presented here in more detail are recommended for additional reading.3,4

Clinical decision making is influenced by health frameworks. Making clinical decisions is a shared responsibility between therapist and client. Therefore an understanding of the therapist’s and client’s health framework is important. The goals of the chapter are to provide enough background information on whole medical systems to aid therapists in (1) understanding specific complementary therapies described in the book (see, for example, acupuncture (Chapter 5), tai chi (Chapter 9), and qigong (Chapter 15), which are specific TCM approaches) and (2) understanding the client, who may be approaching care from a theoretical perspective different from the therapist’s. Each section in the chapter is organized the same way using the following headings: Background, Foundational Principles, Examination and Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Techniques. More detail is provided in the TCM section because the literature available in MEDLINE from 1996 to June 2007 used to evaluate TCM was greater (3420 citations) than Ayurveda (596 citations), naturopathy (281), or Native American Medicine (11). This format is designed to aid the reader in comparison and contrast of the whole medical systems described in the chapter.

AYURVEDA

Background

Ayurveda is a whole medical system that began in India and has evolved over 5000 years.5,6 The word Ayurveda is based on two Sanksrit words, ayur, meaning “life,” and veda, meaning “science” or “knowledge.”6 Ayurveda originated as a spiritual tradition with the evolution into a systematic approach to health and disease.6 Ayurvedic medicine was formalized by the writing of three major and several minor books. Three books in poem form (sutra) are considered the most important texts on Ayurvedic medicine.7 The oldest book, the Charaka Samhita, relates to internal medicine and contains a classification of diseases based on organ systems, including signs and symptoms of ill-defined conditions.6 The definition of health is anchored in a tripod of mind, spirit, and body. The second major text, the Susruta Samhita, was written by the surgery school. In addition to surgery and surgical equipment is a discussion of the human anatomy, including the musculoskeletal, circulatory, and nervous systems. Eight distinct branches of medicine are delineated in the book.6 The third text, the Astanga Hrdayam Samhita, also relates to internal medicine and describes human physiology in addition to therapeutic use of minerals and metals.7 Translation of these three texts in addition to other important books forms the basis of the West’s understanding of Ayurvedic practices.6 Reportedly the Vedic texts were translated into Chinese and influenced the development of TCM in addition to other systems of medicine in Europe and the Middle East.6

Foundational Principles

Ayurvedic practice connects people to a universal context. The universe was created by female and witnessed by male energy.7 This universe is composed of five elements: space, air, fire, water, and earth. All of these elements are believed to be in every human cell.7 Therefore people are a representation of the larger cosmos.8

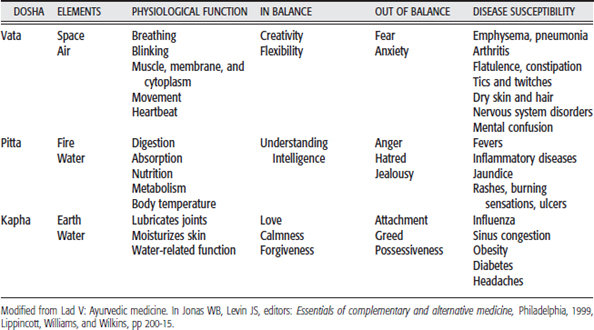

The five elements have three active forms or energies (doshas): vata, pitta, and kapha (Table 4-1).7 The energies are composed of elements found in varying amounts. Vata is composed primarily of space and air and is associated with movement. Pitta is composed primarily of fire and water and is considered the body’s metabolic system, and kapha is composed primarily of earth and water and forms the body structure that holds the cells together.7 Each of these doshas has a body function associated with physiological and personality characteristics in addition to a propensity for certain disease conditions (see Table 4-1). People are composed of the three doshas (tri-dosha) but may have a dominant dosha. The seven normal body constitutions are a combination of the three doshas. The rarest constitution (sama) is one in which the three doshas are balanced perfectly.9

In Ayurveda the anatomy and physiology of the body are organized by tissues, mental states, waste products, and channels. The physical constitution of the body is based on seven tissues: plasma, blood, fat, muscle, bone, nerve, or reproductive. The mental constitution or states are balance (sattva), energy (rajas), and inertia (tamas).9 The body produces three types of waste (malas): feces, urine, and sweat. The body is composed of thirteen channels through which all substances circulate. Knowing one’s own psychological and physiological constitution allows a person to make lifestyle decisions aimed at maintaining equilibrium to live a balanced, happy, and fulfilled life.7 When the doshas are balanced, the person is in a state of health.

Disease occurs when an imbalance exists between mind, body, and consciousness.8 This can be manifested as an imbalance in the doshas in addition to the accumulation of ama.9 Sources of disease can be classified into three categories: external (such as trauma or lifestyle), internal (such as hereditary), or supernatural causes (such as lightning or planetary bodies).9

Examination and Diagnosis

The examination process consists of interview, observation, and physical examination of the individual. Knowledge of the doshas is used as a basis for all aspects of examination. Interviewing includes gaining information about past actions to search for mental imbalances9 in addition to inquiry into a person’s lifestyle. The physical exam, according to Lad,7 has eight clinical modalities. These include examination of the pulse, urine, feces, eyes, touch, general physical exam, and observation of the voice and tongue.

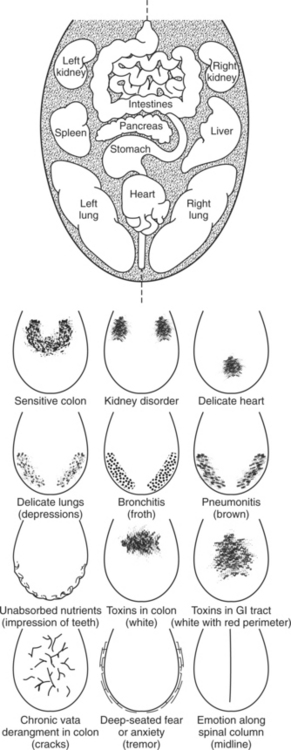

Tongue, pulse, and urine examinations are related to the doshas in addition to the condition of the body tissues. In the pulse examination, done with the ring, index, and middle fingers over the radial artery, each dosha has a distinct form. For example, a pulse resembling a snakelike movement under the index finger is considered a vata pulse.9 A person has 12 different radial pulses, six on each side; three are superficial and three are deep. These pulses correspond to organs and can be used to determine their physiological condition.8 In the tongue examination, the organ systems are mapped to a specific location in the tongue. Tongue discolorations and sensitivities correspond to specific diseases. For example, a black or brown discoloration indicates a vata tongue, whereas a white, pale tongue indicates a decrease in red blood cells and is a kapha tongue (Figure 4-1).8

Similarly, in the urine exam, color and odor are used to identify a dosha or body tissue imbalance. For example, intense yellow, reddish, or blue urine indicates pitta.9 The dropping of sesame oil into the urine also is used to determine the dosha (based on the shape of the drops as they move through the urine, again a snakelike shape is consistent with vata), in addition to the client prognosis (if the drop of sesame oil sinks to the bottom of the vessel, the disease may be very difficult to treat).8 Finally, the odor of the urine is also diagnostic. Foul-smelling urine is an indication of accumulation of toxins, whereas sweet-smelling urine indicates a diabetic condition.8 Many of the exam techniques used in Ayurveda persist in the physical exam even with the advent of new diagnostics.

Diseases are staged according to the balance of the doshas, from the least severe stage of accumulation (too much dosha in a particular organ system) through the provocation stage (irritation of the dosha in the local tissue), spread stage (dosha moving into other systems), deposition stage (dosha disrupting other organ systems), manifestation (signs and symptoms are apparent), and differentiation (tissue damage) stages.7 Interestingly, it is not until manifestation that the cardinal signs and symptoms of the disease are evident. Therefore diagnosis of the disease at the earlier stages can be viewed as preventive, and prognosis worsens as a person moves toward the manifestation and differentiation phases of disease.

Therapeutic Techniques

Interventions are categorized as preventive or therapeutic. Prevention includes a lifestyle that involves knowing a person’s constitution and how to maintain a balance between external and internal forces and then engaging in proper nutrition, exercise (yoga), and purification. The approach to intervention in Ayurvedic medicine is to rebalance the person’s doshas and then to identify the disease. Disease identification includes localization of the specific tissues and channels affected in addition to the staging of the disease.9 Treatment is applied at the physical, emotional, and spiritual level.7 The repertoire of interventions includes diet and herbs, massage, yoga, aroma, color, and music therapies.

Once disease has been identified, a person may go through two types of cleansing and restorative processes: palliation or panchakarma.7 Each of these processes involves the use of herbs, fasting, and exposure to the correct elements and breathing to strengthen the body and eliminate the ama, in addition to lifestyle changes to maintain the benefits of the treatment. Panchakarma, a five-step process, is recommended when individuals have the strength to remove the extra doshas and toxins from the body. After preparatory steps with oil massage and sweat therapy, an individual may undergo therapeutic vomiting, purgatives and laxatives, therapeutic enemas, nasal administration of medications, and blood purification.7 Palliation consists of toxin removal but in a more gentle manner than panchakarma; it includes herbal remedies, fasting, and sunbathing or windbathing.7

The use of herbs in Ayurvedic medicine is extensive. More than 2000 plant species are described in the ancient Ayurvedic texts.10 Herbs have properties just like the doshas. They often can be administered as antidotes to excess dosha. For example, the common cold has properties of kapha, which include mucus, congestion, thickness, and lethargy. Ginger is an herb considered to have the opposite qualities and is given as an antidote.7 Herbs also can be administered to strengthen a body tissue or restore balance in a dosha. Therapies involving exercise, massage, and yoga also are practiced in Ayurveda in addition to therapies that use color.

Evidence

A MEDLINE search (performed on February 12, 2007, of references from 1950 to the present) of the key term Ayurvedic medicine yielded 1290 references with approximately 100 additional references when the key word Ayurveda was searched. No Cochrane topic reviews, three evidence-based medicine reviews,11–13 and 70 clinical trials were found. Two reviews found support for Ayurveda in management of irritable bowel syndrome11 and selected menopausal symptoms.12 The evidence for the use of Ayurveda for the management of arthritis was lacking.13

A subset of articles dealt with the validation of the dosha concepts.14–16 The authors used different approaches to validate independently the existence of the doshas. Support for the construct of doshas was found by relating them to thermodynamics16 with use of an algorithmic heuristic approach,15 and identification of an invariant co-enzyme that the authors proposed was a unifying construct for all organisms.14 In each study the dosha identification of hundreds of subjects was compared with the independent measurement.

Many clinical trials were conducted to determine the efficacy of plant preparations and Ayurvedic herbs. Applications were to varied client populations or medical conditions such as Parkinson’s disease,17,18 hepatitis,19,20 diabetes,21–26 asthma,27–29 osteoarthritis,30 insomnia,31,32 acne,33,34 rheumatoid arthritis,13,35,36 obesity,37,38 and jaundice.39 Effects of herbs on memory,40 cognition,41 and decline of vision with aging42 also were studied.

Support for Ayurveda was reported in the treatment of insomnia, diabetes, asthma, acne, and cognition. Ayurvedic herbs were found to decrease sleep latency in healthy adults,32 whereas yoga was superior to an Ayurvedic herb for improvement of sleep in the elderly.31 In the management of diabetes, improvements were found in the HbA1c levels of a subgroup of clients who took pancreas tonic24; and cogent db (an Ayurvedic herbal supplement), when added to allopathic medicines, improved client’s blood profile without any adverse kidney effects.25 Asthma symptoms were alleviated completely in a group of children who discontinued their allopathic medication and replaced it with an herbal supplement27; anti-asthmatic effects also were reported for adults in a combined clinical study with a corroborating animal model.28 Acne preparations administered internally and externally were found to be superior to oral administration alone.33 Finally, aspects of cognition related to memory and retention of newly learned information41 also were reported.

Whole system or multimodality Ayurveda was studied in only two populations.43,44 Clients with type II diabetes who were treated with Ayurveda consisting of diet, exercise, meditation, and an herb supplement were compared to a control group who had standard diabetes education classes and a follow-up with a primary care health care provider. For a subset of clients with elevated glycosylated hemoglobin, Ayurveda had better outcomes, including reduced weight, cholesterol levels, and fasting glucose, than the controls.44 Similar findings were reported for elderly subjects with coronary heart disease (CHD) of varying risk levels. Three groups—multimodal Ayurvedic (labeled Maharishi Vedic Medicine, or MVM), modern, and usual care—were studied for 1 year. The MVM group participated in a program to promote health and decrease the risk of disease. The program included transcendental meditation, an herbal supplement high in antioxidants, Vedic diet (seasonal variation of low-fat high fruit and vegetable diet), yoga, and walking. The modern care group had modifications in their exercise and diet, and took a placebo vitamin. The usual care group did not receive interventions. On the primary outcome measure of intima-media thickness (IMT), a measure of atherosclerosis, there was a significant decrease for the high-risk CHD clients in the MMV group compared with the modern care and usual care groups. These studies are interesting because they focus on prevention of disease and present promising findings for a multimodal approach.

TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE

Foundational Principles

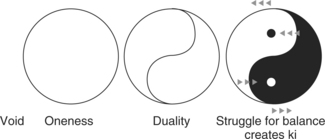

The first fundamental principle of TCM is based on the Taoist concept of yin and yang.45 Yin-yang theory is based on the philosophical construct of two polar but complementary opposites (Figure 4-2).

These complementary opposites are used to explain the continuous process of natural change and describe how things function in relation to one another and to the universe. In this system of thought all things are seen as part of a whole and can be explained only by relative relationships to other entities.46 This is demonstrated graphically in Figure 4-2, in which yin is signified by black relative to the white of yang; and yet within yin is a component of yang, and vice versa. The curve separ-ating yin and yang indicates that it is a gradual transition from yin to yang.

Some of the correspondences of yin and yang in nature and in the body are summarized in Table 4-2. This table demonstrates that yin-yang theory is used to describe the human body (organs, tissues, fluids) and its functions. Disease (or disharmony) in the body is caused by a relative imbalance of yin and yang, and therefore the aim of any treatment (either herbal or acupuncture) is to prevent an imbalance or rebalance of any disharmony. (See the section on the Eight Principle Patterns on p. 42.) A simple example of disharmony of yin and yang could be seen in the regulation of a client’s temperature. For example, from Table 4-2 yang is hot and thus provides heat or warmth for the body, whereas yin is cold, and this cools the body. Normally if yin and yang are balanced, the body should feel neither too hot nor too cold; however, if an excess of yang exists, as could happen in an acute sports injury, then part of the body will feel hot. By contrast, if an excess of yin exists because of a longstanding chronic illness, the person will feel cold, and parts of the body will feel cold to the touch.

Table 4-2 Yin-Yang Correspondences in Nature and the Body

| YIN | YANG | |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Night | Day |

| Cold | Heat | |

| Stillness | Movement | |

| Body structure | Internal | External |

| Solid organs | Empty organs | |

| Ventral | Dorsal | |

| Physiological function | Nutritive substances | Functional activities |

| Storage | Movement | |

| Pathological changes | Cold | Heat |

| Diagnosis | Interior | Exterior |

| Deficiency | Excess | |

| Cold | Heat |

This balance of yin and yang is controlled by a vital force or energy called qi (pronounced “chee”), which circulates between the organs along channels called meridians45 (see also Table 5-1, Chapter 5). Although the meridians are proposed to carry qi and blood through the body, they are not blood vessels but rather are an invisible network that links all the fundamental substances and organs. Fundamental substances are described by Kaptchuk46 and can be summarized as the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree