Abstract

Introduction

Pressure ulcer (PU) is a common complication in chronic affection, especially neurological disorders and diseases commonly diagnosed in the elderly. For a long period of time, the prevention of skin lesions was taught only in an empirical manner. The development of therapeutic patient education (TPE) sheds a new light on care management for patients with chronic pathologies.

Objectives

Determine the place of TPE in persons at risk of and/or already suffering from pressure ulcer (PU) as of 2012.

Methods

The methodology used is the one promoted by SOFMER, including: a systematic review of the literature with a query of the PASCAL Biomed, PubMed and Cochrane Library databases for data from 2000 through 2010; a compendium of prevailing professional practices and advice from a committee of experts.

Results

The review of the literature found six studies including four controlled trials in patients with chronic neurological impairments (most of them with spinal cord injury). No studies were found regarding the elderly. The level of evidence for efficacy in persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) is moderate. The clinical practice study focuses on programs currently underway, dedicated to SCI patients or elderly populations.

Discussion

The approach proposed through TPE has its role in a strategy aimed at preventing PU in persons at chronic risk of developing PU. The educational objectives and techniques used must be adapted to the clinical and psychological context and are debated in this review. The co-construction of programs, recommended in the official texts on therapeutic education in France, should help to tailor these programs to the patients’ needs.

Conclusion

TPE is relevant in care management or prevention of PU in persons at chronic risk, patients with spinal cord injury (Grade B) or elderly subjects (Grade C).

Résumé

Introduction

L’escarre est une complication fréquente dans certaines pathologies chroniques, notamment neurologique ou chez les personnes âgées. L’apprentissage de la prévention cutanée a été pendant longtemps réalisé de manière empirique. Le développement de l’éducation thérapeutique du patient (ETP), apporte un éclairage nouveau sur la prise en charge des personnes atteintes de pathologie chronique.

Objectifs

Déterminer la place de l’ETP chez les personnes à risque et/ou porteurs d’escarres en 2012.

Méthode

La méthodologie utilisée est celle de la SOFMER, comprenant : une revue systématique de la littérature avec interrogation des bases de données PASCAL Biomed, PubMed et Cochrane Library entre 2000 et 2010 ; un recueil des pratiques professionnelles et l’avis d’un comité d’expert.

Résultats

La revue de la littérature a retrouvé six essais dont quatre contrôlés sur des chez le sujet atteint de déficience neurologique chronique (lésé médullaire surtout). Il n’existe aucun essai chez le sujet âgé. Le niveau de preuve d’efficacité est modéré chez le lésé médullaire. L’enquête des pratiques révèlent des programmes en cours de développement, s’adressant aux personnes lésées médullaires ou âgées.

Discussion

L’approche proposée par l’éducation thérapeutique du patient trouve sa place dans la stratégie de prévention des escarres chez les personnes à risque chronique d’escarre. Les objectifs pédagogiques ainsi que les techniques pédagogiques utilisées doivent être adaptées au contexte clinique et psychologique et sont discutés dans cet article. La co-construction des programmes, préconisée par les textes régissant l’éducation thérapeutique en France, permet de s’assurer de l’adéquation des programmes aux besoins des patients.

Conclusion

L’ETP a un intérêt dans la prise en charge ou la prévention de l’escarre chez les patients à risque chronique, sujets âgés (Grade C), lésé médullaire (Grade B).

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Therapeutic patient education (TPE) in chronic diseases is a form of learning that allows the patient to get to know his disease and its treatment in such a way as to take care of himself to the greatest possible extent . Patients presenting with chronic diseases necessitate a form of care management promoting balance between the practical training required for self-care and the psycho-affective adjustments engendered by any chronic affliction. Therapeutic education allows for pedagogical choices favoring acceleration of skill development in health care while respecting their appropriation by the patient. To sum up, therapeutic education is aimed at the acquisition of competences contributing to preservation and growth of the patient’s “health capital”.

In France, TPE development is part and parcel of public policy meant at once to improve the quality of life of patients with chronic illnesses and to master the health-related expenses arising from the latter. The annual rise in the number of long-term illnesses (ALD, in French) is estimated at 6.7%, and additional expenses over the coming years are to be expected, given the aging of the population and the steepened costs connected with modern medical technical wizardry.

The first mention of TPE in a French quality context may be found in the February 1999 health establishment accreditation manual: “The patient should be able to benefit both from educational action as concerns his illness and its treatment, and from health-related educational, action adapted to his needs”. A law dated 4 March 2002 known as the “Kouchner law” and pertaining to patients’ rights and health system quality, recognizes the patient’s right to information on his state of health, and casts him as “actor/partner, beside the professionals, with regard to his health”. In June 2007, the French high health authority (HAS) published a methodological guide aimed at “structuring a TPE program in the field of chronic illnesses”. The role of TPE in the French health care system entered into French jurisprudence in 2009 with enactment of the “HPST” law, which mandated hospital reform and explicitly referred to patients, health and territories. The law follows the guidelines put forward by the HAS and goes on to define a regulatory framework along with the modes of financing.

Pressure ulcer (PU) is not a chronic disease, but rather a complication in cases of immobility. The highly diversified contexts in which such ulcers occur contribute in different ways to their evolution. For instance, in the event of transitory immobility, prognosis for the ulcer is connected with prognosis for the pathology leading to immobility. On the other hand, prognosis is multifactorial for persons presenting chronic neurological deficiency or for the aged. Indeed, these persons present at least one chronic pathology exposing them permanently or regularly to pressure ulcer (PU) risk. The chronic pathology context necessitates adaptation of medical caretaking procedures, which means that the patient has got to be accompanied with regard to understanding and acceptance of the pathology along with the complications it entails. More precisely, the patient’s role in prevention and treatment of the ulcer should be enhanced in such in a way that he may effectively do something about the disease. TPE is one possible approach.

Through the PU consensus organized in 2011, the work group bringing together four French specialized medical associations (SFGG, SOFMER, SFPC, PERSE) endeavored to discuss the role of TPE in the management of PU patients. The analysis of the literature and exchange of ideas that was to follow would be limited to persons at chronic risk of PU sore such as the aged and individuals with chronic neurological deficiencies. These types of patients require long-term, highly complex health care management, and since aggravation of their chronic disorders is virtually inevitable, their cases render necessary an ongoing adaptation of usual medical care and management techniques.

1.2

Objective

The objective of this article is to draw up recommendations for clinical practice with regard to therapeutic education in the prevention and treatment of pressure sores in chronic diseases.

1.3

Material and methods

Elaborated by SOFMER , the method employed involves three main steps: a systematic review of the literature, a compendium of prevailing professional practices and validation by a multidisciplinary panel of experts.

1.3.1

Systematic review of the literature

The methodology of the systematic review was established on the basis of recommendations from the Cochrane Library .

1.3.1.1

Inclusion criteria

Only clinical trials were included in this study. Cross-sectional studies, case-control and cohort studies, case reports and case series were rigorously excluded. The articles had to be written in English or French. The population under consideration had to consist of human adult subjects. The “PU” variable was taken into accounts whatever the criteria of judgment applied (clinical or questionnaire-based), and it was described with regard to each study, as were the intermediate clinical or psychosocial judgment variables.

1.3.1.2

Bibliographic research strategy

A systematic interrogation of databases constituted from 2000 through 2010 was carried out by two professional documentarians. The databases used were: PASCAL Biomed, PubMed and Cochrane Library.

The English key words were: pressure sore; pressure ulcers; prevention and control; risk reduction behavior; patient education; individual patient education; collective patient education; family education; health education; evaluation; practice guidelines; evidence-based medicine and evidence-based nursing. Their French counterparts were: escarres ; patient ; famille ; éducation thérapeutique ; programme individuel ou en groupe ; évaluation ; médecine fondée sur les preuves .

1.3.1.3

Steps and stages of the review

1.3.1.3.1

Article selection

The articles selected by the documentarians were proposed to a medical bibliography selection committee consisting in doctors representing PERSE, SFGG, SFFPC and SOFMER.

An initial selection of articles was carried out independently by the same committee in order to pinpoint those relevant to the general theme. The complete articles in an electronic or paper format were then transmitted to two experts.

A second selection was then performed by the two experts, one from the SOFMER and the other from the SFGG, on the basis of their readings of the “materials and methods” paragraphs and with the objective of retaining articles dealing with TPE. Lastly, the apparently pertinent abstracts of the articles cited as references were analyzed.

1.3.1.3.2

Data extraction and assessment of methodological quality

The studies meeting the inclusion criteria were analyzed by two readers using a standardized reading grid, which pertained to the type of study, the population selected, the health and education models employed, the data collection method, definition on the variables analyzed, statistical analysis and the results and the biases found for each study. The methodological quality of the articles chosen for analysis was determined on the basis of the ANAES grid through which studies are classified according to four levels. The studies presenting poor methodological quality (inadequate randomization, insufficient number of subjects, imprecision as to the interventions) were excluded.

Since there exists no well-founded proof that “blind” data extraction eliminates the biases of a systematic review , it was not carried out. The two readers subsequently compared their evaluations and diminished their disagreements through discussion.

1.3.1.3.3

Data analysis

The data originating in clinical trials were analyzed according to population profile and the sub-jacent health-based and educational models.

Schematically speaking, we distinguished two health-based models: a biomedical model (being in good health means not being ill) and an overall or global model (being in good health means a state of physical and moral well-being), along with two educational models according to the objectives set: observational (the physician decides), shared responsibility (the patient and the physicians set the objectives together) and self-determination (the patient sets his own objectives).

1.3.2

Compendium of prevailing professional practices

The compendium of professional practices dealing with the role of TPE in PU care management was carried out with a representative sample of the participants at the nationwide congresses of the four participating societies (PERSE, SOFMER, SFGG and SFFPC) in the form of a yes/no or multiple choice questionnaire ( Appendix 1 ), the responses being recorded through an electronic system.

1.4

Results

1.4.1

Review of the literature

1.4.1.1

Bibliographic research

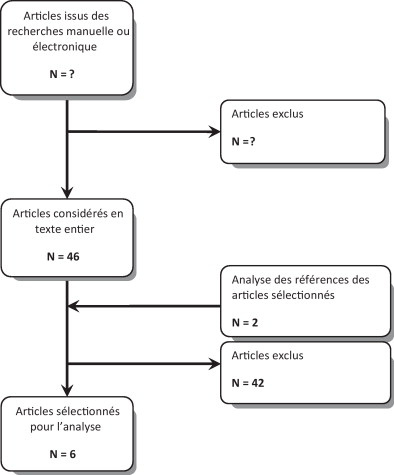

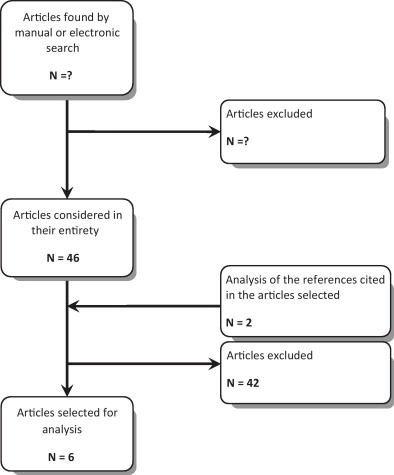

Initial analysis of the articles selected for interrogation of the data bases from the titles and the abstracts resulted in preliminary inclusion of 46 articles ( Fig. 1 and Table 1 ). Analysis of the references led to the addition of two supplementary articles. A second analysis, which pertained to the complete texts, resulted in exclusion of 41 articles. All and all, analysis of the literature involved six articles.

| Title HAS quality | Type of trial Health model Educational model | Population | Protocol | Criteria used and analyzed | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 Phillips Level 2B | Open RCT Biomedical Compliance | 111 SCI Average age 35 years Initial phase Follow-up over 1st stay and 1 year after discharge | G1 ( n = 36) Individual education (1/week, 5 weeks) by telemedicine Themes = PU, nutrition, bladder-sphincter and elimination, psychosocial, technical assistance) G2 ( n = 36) Individual education (1/week, 5 weeks) by telephone Themes idem G3 ( n = 39) control | Depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale) QoL (Quality of Well Being Scale) | NS S (G1 + 2 versus G3) |

| 2002 Garber Level 2B | Open RCT Biomedical Compliance | 41 SCI Age = 53 Tetra = 39% Initial phase Follow-up admission-discharge | G1 ( n = 20) Theme-based education (pressure ulcer [PU]): 4 × 1 h individual Information booklet Monthly motivational telephone follow-up G2 ( n = 20) = control | Pressure ulcer Knowledge Test (not validated) | NS |

| 2003 Jones Level 4 C | Free trial Biomedical Compliance | 12 SCI Secondary phase Repeated PU sore | Individual educational evaluation with outpatient nurse after-care, treatment contract Outpatient nurse after-care (rhythm changing according to PU development) Financial reward with skin result (max 50 $ by visit, bonus 250 $ if no PU, every 4 months until 2 years) | Number of sores and severity (PUSH v3) Health care cost before/during/after program | Improvement during program, aggravation following the end Before: $ 6263/month/person During: $$235 After: $ 2305 |

| 2004 Ward Level 2B | Open RCT Biomedical Compliance | 114 Patho ND (including 55 PKD, 45 MS) Age = 63 years | G1 ( n = 57) Individual educational evaluation by OT Themes: fall and pressure ulcer sore Meeting of professionals to target objectives Home visit by OT (standardized information; individualized brochure) Motivational telephone conversation on D15 G2 ( n = 57) control Simple telephone follow-up every 2 months for 1 year | Annual incidence of PU or fall Functional independence NEADL Perceived well-being GHQ (patients and assistants) | S: aggravation in study group for the 2 criteria NS to M12 NS to M12 |

| 2005 May Level 4 C | Free trial Biomedical Compliance | 23 SCI Tetra = 30% Initial phase Follow-up M0-M6 | Group workshop, twice a week for 8 weeks, 12 themes (spinal cord functioning, pressure ulcer core, bladder-sphincter, elimination, the autonomic system, blood circulation, sexuality, technical assistance, the wheelchair, home adjustments and accommodations, etc.) | Knowledge questionnaire (29 items, not validated) Problem-solving (Life Situation Scenario) Perceived importance of the themes | S NS No modification |

| 2008 Rintala Level 2B | Open randomized controlled trial Biomedical Compliance | n = 41 SCI Secondary phase (Postoperatory pressure sore surgery) Tetra = 39% Follow-up over 2 years | G1 ( n = 20) 4-hour individual workshop (theme: PU) Information booklet Monthly motivational telephone follow-up G2 ( n = 11) Simple monthly telephone follow-up G3 ( n = 10) Quarterly follow-up by mail | PU recurrence 2 years after Time lapse before recurrence | 33%/60%/90% P = 0.007 19,6/10,1/10,3 P = 0.002) |

1.4.1.2

Characteristics of the studies excluded

Among the studies excluded, 14 dealt with caretaker training, nine consisted in recommendations for clinical practice with regard to PU, eight were reviews of the literature on PU, seven had to do with health psychology, five took up the organization of pressure sore treatment, one clinical trial was irrelevant, and the last was an editorial along with a series of TPE cases.

1.4.1.3

Characteristics of the studies included

Analysis of the literature was brought to bear on six studies: four randomized controlled trials and two free clinical trials . The number of patients included varied from 12 to 114 for a total of 342 patients.

The population consisted in either person with spinal cord injuries during the initial stage or the chronic stage or persons presenting with degenerative neurological (multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease) but in this particular case, only one study had been collected . No study was performed in the elderly subject.

The health model subjacent to the trials was always biomedical. The educational model was invariably built around an objective of patient compliance; the pedagogical objectives were decided upon by the caretakers, and not consented to by the patients.

1.4.1.4

Methodological quality of the studies

Rating of the methodological quality of the studies through application of the relevant ANAES criteria showed no inconsistency or discrepancy between the two authors. Among the studies selected, four articles presented level of evidence 2 and level of recommendation B, while two articles showed level of evidence 4 and level of recommendation C.

1.4.1.5

Data analysis

1.4.1.5.1

Trials dealing with therapeutic patient education in elderly persons

In the literature, no study has been found on elderly persons suffering from chronic medical pathologies and at risk of PU.

1.4.1.5.2

Trials dealing with therapeutic patient education in persons suffering from neurological deficiency

Clinical variables . Among persons presenting with a spinal cord wound, the clinical impact of a TPE program was found in two clinical trials. Jones et al. carried out a non-comparative trial of limited power in aged persons repeatedly presenting with PU sores. Financial incentives were proposed. The impact was positive in a before/after comparison with regard to PU occurrence and severity. The second study , a controlled randomized therapeutic trial of limited power, was carried out postoperatively with a musculo-cutaneous flap in spinal cord PU patients. Two years after the intervention, the recurrence rate and the time lapse prior to recurrence demonstrated the beneficial effects of an educational approach (33% recurrence in the treated group vs. 90% recurrence in the control group; P = 0.007 and 19.6 months versus P = 0.002 and 10.2 months).

As regards persons presenting with a progressive neurological condition (multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson disease (PKD)…), we have found a comparative trial of limited power. Ward et al. noted significantly higher PU occurrence in the intervention group than in the control group. There was no secondary analysis taking into account the patients’ cognitive disorders.

Functional variables . In a controlled randomized trial of limited power , quality of life was assessed one year after an educational program addressed to newly injured spinal cord patients. The authors noted a perceived improvement in the intervention group of quality of life, which was assessed in accordance with the Quality of Well Being Scale.

In the just-mentioned comparative trial, Ward et al. did not find any effect on quality of life, which was assessed in patients and family caretakers in accordance with the General Health Questionnaire. As for functional autonomy, which was evaluated through use of the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living scale, it underwent no modification in the intervention group.

Psychological variables . One year after the conclusion of an educational program addressed to newly injured spinal cord patients, Philips et al. did not note any impact on depression.

Cognitive variables . The effect of a TPE program on patients’ knowledge levels has been discussed. In a free trial of limited power , May et al. noted improvement in this respect following a multi-themed workshop addressed to newly injured spinal cord patients. On the other hand, in a comparative trial of limited power, likewise addressed to newly injured spinal cord patients, Garber et al. found no improvement in knowledge level following a single-themed program on PU sores. The knowledge questionnaire failed to be validated in either case.

In a previously described trial, May et al. did not note any effect on problem resolution strategies.

Medico-economic aspect . In a non-comparative trial of limited power addressed to spinal cord patients presenting with repeated PU, Jones et al. carried out a medico-economic demonstration pertaining to the impact of an observational, behaviorist study with financial incentives for observing patients. While the program was underway, medical expenses incurred in skin care were divided on the average by 30, only to rise again once the program was over.

1.4.2

Compendium of prevailing professional practices

Questioning by the audience at nationwide congresses has shown that in the participating associations, TPE is far from widespread; in fact, formalized TPE programs exist in less than one third of the associations’ structures. When they function, they are addressed to spinal cord patients and/or elderly persons.

1.5

Discussion

In France, the methodological framework published in 2007 by the high French health authority and the national institution of health prevention and education is less prescriptive than advisory, and it is aimed at accompanying treatment teams as they build and follow up on an appropriate program. The present article pursues this objective, with regard to primary or secondary PU prevention in persons at chronic risk, as the relevant literature is reviewed and practices on the ground are taken into account. The following observations ensue.

Firstly, we have noted the low level of evidence as regards therapeutic education in the management of persons suffering from chronic illnesses and at risk of PU. The weakness is due to the small number of studies found, to the low number of participants, and also to pervasive methodological shortcomings. The small number of studies may be partially explained by the relative newness of TPE, especially as concerns chronic illnesses in dependent persons requiring the support and care management provided by a family aide or caregiver. The first relevant study dates back only to 2001, and it confirms the newness of the approach. Moreover, most of the studies since that date have involved only a limited number of patients, which means that their statistical power is equally limited, and usually does not suffice to underscore any therapeutic effect in the absence of preliminary calculation of minimum trial sample size.

The second observation has to do with the subjacent health and education models; all of the studies were carried out according to a biomedical model and with the objective of therapeutic compliance, and this was duly noted in an overview of the contexts in which an educational approach has been developed . Biomedical models are intuitively adopted by the medical profession when physicians think in terms of “educating” a person suffering from chronic illness, and this inclination most likely stems from their initial training. That said, up until now medical studies have generally been lacking in programs focused on pedagogy, techniques in health education or on therapeutic education itself. The development a patient’s ability, in conjunction with his entourage, to effectively combat his disease under different circumstances is known as empowerment, and it constitutes a key dimension of therapeutic education that was not taken up in any of the studies under consideration.

The third observation involves learning models, many of which may be found in the literature. It is not our objective in this paper to define an optimal model; we simply wish to draw the attention of the reader to a key point, which is that the model chosen for use must be tailored to the person to whom it is addressed. Some people learn by experience, as is the case, for instance, in the open study conducted by Jones et al. The authors employed a behaviorist model, with a financial reward being given to patients with skin in satisfactory condition as reinforcement of their suitable behavior. The persons included were spinal cord patients with repeated PU occurrence, and their psychosocial profile was stereotyped (single man, jobless, low skill level). The results were encouraging; while the study was underway, American insurance companies were spared numerous expenses, the patients enhanced their income levels and their skin condition improved. Other people are likely to seize the interest of cutaneous prevention based on discussion and exchange between professionals and peers, as may be seen in the Phillips trial. The learning model he and his team implemented was characterized as constructivist, as it was focused on how the person’s representations of the sore and its prevention came to evolve. The hypothesis put forward was that once the latter are modified, health-based behavior such as proper skin care will likewise change.

The literature does not supply precise answers to questions concerning the pedagogical objectives to be proposed to patients at long-term risk and/or to their family caregiver. As of today, these objectives are often drawn from the experience of the health care professionals accompanying persons at risk in physical medicine and rehabilitation establishments. With regard to spinal cord patients, for example, we classically make distinctions between:

- •

what needs to be known (pressure sore mechanism, risk-heightening situations, locations to be closely monitored;

- •

what needs to be technically mastered (skin care surveillance practices, prevention equipment quality, garment adequacy, urinary catheter positioning…);

- •

what needs to be behaviorally mastered, that is to say how to adapt in a timely way (showing reactivity in the event of rash or redness, altering surveillance routine according to perceived risk, knowing when to contact a health care professional…).

The TPE conceptual framework is designed to promote confrontation between on the one hand specific objectives as determined by professionals, and on the other hand the needs and wishes expressed by patients; to our knowledge, this type for pooled building or co-construction has yet to come into being.

Lastly, the objectives and modalities of a TPE program have got to be tailored to the population involved. As regards elderly persons, the studies reviewed do not presently suffice to circumscribe the interest of TPE care management for pressure sore. The possible inclusion of caregivers was dealt with in only one, non-contributive study, and no work has been carried out in aged individuals. For these reasons, extrapolation towards actual case management appears hard to envision, and it bears mentioning that one of the studies under consideration yielded negative results in patients presenting chronic neurological pathologies at times associated with cognitive disorders, which are quite frequent in the aged subjects for whom these recommendations are likely to be relevant. And yet, in the context of Alzheimer’s disease and related illnesses, therapeutic education is one of the non-drug treatments showing a high level of evidence and having a positive effect in terms of delaying loss of autonomy and institutionalization, as well as caregiver depression . It would appear worthwhile to develop these educational programs in the elderly subject, and involvement of the family caregiver would be particularly helpful. When associated with neurodegenerative pathologies, old age progressively leads to greater and greater dependency, which cannot possibly be managed by the professionals alone. And it should once again be stressed that from initial orientation onwards, these programs should include caregivers, that is to say the persons of first resort in home assistance; in the research carried out up until now, they have been largely neglected .

As for the persons presenting stable neurological deficiency, with spinal cord patients constituting the main example, studies have been more numerous. Educational programs have been proposed in two different contexts. The first one takes place in the initial treatment phase for newly injured spinal cord patients in physical medicine and rehabilitation. The programs go into different aspects of the wound along with its possible medical complications, including pressure sore, and its psychosocial consequences . The main aim of these programs is to facilitate construction of health-based images or representations of the neurological wound and, more particularly, of secondary complications in view of better enabling the patients to effectively combat their disease. The pedagogical techniques to be employed need to be fully thought out, as does their psychological impact during a period of adjustment to a handicap. As concerns PU, it would appear necessary to instill the ABCs of prevention without dramatizing or shaming the patient; that is why it does not seem useful to show him photos of the sore for educational purposes. The psychological shock that is frequently reported in “exposed” patients may have unexpected consequences ranging from perpetual anxiety with regard to the sore to blanket denial of any risk. As for the second context, it involves patients in a chronic phase with regard to the wound and who run the risk of contracting sores. The programs that have been developed are focused on this complication, and they generally consist in a series of group sessions followed up by motivational actions (regularly scheduled phone discussions, the occasional financial reward…). They are addressed to persons generally already in possession of a clearly defined image of the sore, and that is one of the reasons why they are long-term. Their impact has been demonstrated as regards sore recurrence (level of evidence B) and has been studied to a lesser extent from a medico-economic standpoint (level of evidence C). On the other hand, there exists no conclusive element on the psychological impact of this type of program, especially as pertains to anxiety, not to mention cognitive impact and a sense of perceived effectiveness.

1.6

Conclusion

TPE is of interest in PU management or prevention in patients at chronic risk, elderly subjects (Grade C) and/or spinal cord patients (Grade B). The attendant programs’ pedagogical objectives have got to be closely adapted to the needs of both the ailing person and his or her family caregivers (professional agreement). It is preferable to employ several educational and pedagogical models so as to tailor them to the person’s preferred way of learning (professional agreement). Last but not least, motivational follow-up is recommended (professional agreement).

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Appendix 1

- •

In your structure, do you run a formalized therapeutic education program for patients? Yes, No

- •

Your formalized therapeutic education program is addressed to:

- ∘

Spinal cord patients A

- ∘

Elderly subjects B

- ∘

Others C

- ∘

- •

You implement your program:

- ∘

For patient groups A

- ∘

For individuals B

- ∘

Both C

- ∘

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’éducation thérapeutique dans les maladies chroniques est l’apprentissage qui permet l’appropriation de sa maladie par le patient, lui permettant de connaître mieux son traitement et sa maladie . Les patients présentant des maladies chroniques nécessitent une prise en charge permettant un équilibre entre l’apprentissage pratique nécessaire pour réaliser des autosoins, et les réaménagements psychoaffectifs qu’engendre toute maladie chronique. L’éducation thérapeutique permet des choix pédagogiques favorisant l’accélération des transformations des compétences de santé tout en veillant à respecter leur appropriation par le patient. Le but de l’éducation thérapeutique est donc d’acquérir des compétences pour entretenir et développer son capital santé.

En France, le développement de l’éducation thérapeutique du patient (ETP) s’inscrit dans une politique publique d’amélioration de la qualité de vie des patients atteints de pathologies chroniques, et de maîtrise des dépenses de santé liée à celles-ci. L’augmentation annuelle du nombre d’affections longue durée (ALD) est estimée à 6,7 %, avec une augmentation du coût prévisible dans les années à venir, compte tenu du vieillissement de la population et de l’augmentation des coûts liés à la technicité de la médecine.

La première mention faite à l’ETP dans la démarche qualité française se trouve dans le manuel d’accréditation des établissements de santé en février 1999 : « le patient doit pouvoir bénéficier d’action d’éducation concernant sa maladie et son traitement, ainsi que d’action d’éducation pour la santé adaptée à ses besoins ». La loi du 4 mars 2002 relative aux droits des malades et à la qualité du système de santé, dite « loi Kouchner » reconnaît le droit à l’information du patient concernant son état de santé, et le place en « acteur partenaire de sa santé avec les professionnels ». La Haute Autorité de santé (HAS) publie en juin 2007, le guide méthodologique de « structuration d’un programme d’ETP dans le champ des maladies chroniques ». La place de l’ETP dans le système sanitaire français sera inscrite dans le droit français en 2009 par la loi portant réforme de l’hôpital, et relative aux patients, à la santé et aux territoires, dite loi HPST. La loi reprend les grandes lignes proposées par le guide de la HAS et définit un cadre réglementaire, ainsi que les modalités de financement.

L’escarre n’est pas une maladie chronique, mais une complication de l’immobilité. Le contexte clinique très divers dans lequel survient une escarre détermine en grande partie son évolution. Pour exemple, en cas d’immobilité transitoire, le pronostic de l’escarre est lié au pronostic de la pathologie responsable de l’immobilité. En revanche, le pronostic est plurifactoriel pour des personnes présentant une déficience neurologique chronique ou des personnes âgées. Ces personnes présentent une ou des pathologies chroniques qui les exposent de manière permanente ou régulière au risque d’escarre. Cela nécessite une adaptation de la prise en charge médicale au contexte de pathologie chronique, avec un accompagnement du patient dans la compréhension et l’acceptation de sa pathologie et de ses complications et dans l’amélioration de sa participation à la prévention ou au traitement de l’escarre, en développant par exemple sa capacité d’agir sur sa maladie. L’ETP peut être une réponse à cette problématique.

À travers le consensus formalisé sur l’escarre organisé en 2011, le groupe de travail regroupant quatre sociétés savantes médicales françaises (SFGG, SOFMER, SFPC, PERSE) a souhaité abordé la question de la place de l’ETP dans la prise en charge de patients porteurs d’escarre. L’analyse de la littérature et la réflexion qui suivra se limitera aux personnes à risque chronique d’escarre que constituent les personnes âgées et les personnes porteuses de déficiences neurologiques chroniques, ces patients demandant une prise en charge au long cours et très lourde, avec l’aggravation des troubles chroniques inéluctable, rendant nécessaire l’adaptation de la prise en charge médicale classique.

2.2

Objectif

L’objectif de cet article est d’élaborer des recommandations pour la pratique clinique concernant l’éducation thérapeutique dans la prise en charge ou la prévention de l’escarre dans les maladies chroniques.

2.3

Matériel et méthode

La méthode utilisée, développée par la SOFMER comporte trois principales étapes : une revue systématique de la littérature, un recueil des pratiques professionnelles et une validation par un panel pluridisciplinaire d’experts.

2.3.1

Revue systématique de la littérature

La méthodologie de la revue systématique a été établie à partir des recommandations de la Cochrane Library .

2.3.1.1

Critères d’inclusion

Seuls les essais cliniques ont été retenus dans cette étude. Les études transversales, cas–témoins et de cohorte, les cas rapportés et séries de cas ont été exclues. Les articles devaient être écrits en anglais ou en français. La population concernée devait être constituée de sujets adultes humains. La variable « escarre » a été prise en compte quel que soit le critère de jugement utilisé, clinique ou issu d’un questionnaire, et a été décrit pour chaque étude. Les variables de jugement intermédiaires cliniques ou psychosociales ont également été décrites pour chaque étude.

2.3.1.2

Stratégie de recherche bibliographique

Une interrogation systématique des bases de données de 2000 à 2010 a été effectuée par deux documentalistes professionnels. Les bases de données utilisées ont été : PASCAL Biomed, PubMed et Cochrane Library.

Les mots clés utilisés ont été en anglais : pressure sore, pressure ulcers, prevention and control, risk reduction behaviour, patient education, individual patient education, collective patient education, family education, health education, evaluation, practice guidelines, evidence-based medicine, evidence-based nursing et en français : escarres, patient, famille, éducation thérapeutique, programme individuel ou en groupe, évaluation, médecine fondée sur les preuves.

2.3.1.3

Déroulement de la revue

2.3.1.3.1

Sélection des articles

Les articles sélectionnés par les documentalistes ont été proposés au comité médical de sélection de la bibliographie constitué de médecins représentants PERSE, SFGG, SFFPC, SOFMER.

Une première sélection d’articles sur résumé a été réalisée de façon indépendante par ce même comité afin de retenir les articles traitant bien de la thématique. Ces articles sous forme de texte intégral ont été transmis sur support électronique ou sur papier à deux experts.

Une deuxième sélection a alors été faite par les deux experts, l’un de la SOFMER et l’autre de la SFGG afin de retenir les articles traitant d’éducation thérapeutique à partir de la lecture du paragraphe de matériel et méthode des articles déjà sélectionnés. Enfin, une analyse des résumés des articles cités en références dans les articles retenus et qui apparaissaient pertinents a également été faite.

2.3.1.3.2

Extraction des données et évaluation de la qualité méthodologique

Les études remplissant les critères d’inclusion ont été analysées par deux lecteurs à l’aide d’une grille de lecture standardisée. Cette grille de lecture comprenait le type d’étude, la population sélectionnée, les modèles de santé et éducatifs utilisés, le mode de recueil des données, la définition des variables analysées, l’analyse statistique, les résultats ainsi que les biais pour chaque étude. La qualité méthodologique des articles retenus pour analyse est faite à partir de la grille de l’ANAES qui permet de classer les études selon quatre niveaux. Les études de très faible qualité méthodologique (randomisation inadéquate, nombre de sujets, intervention imprécises) sont exclues.

L’extraction des données n’a pas été réalisée en aveugle, car il n’y a aucune preuve fondée que cette pratique diminue les biais d’une revue systématique . Les deux lecteurs ont ensuite comparé leur évaluation et réduit leur désaccord par discussion.

2.3.1.3.3

Analyse des données

Les données issues des essais cliniques ont été analysées en fonction du profil de population, du modèle de santé et du modèle éducatif sous-jacents.

De manière caricaturale, nous avons distingué deux modèles de santé : le modèle biomédical (être en bonne santé signifie ne pas être malade) et le modèle global (être en bonne santé signifie un état de bien-être physique et moral), ainsi que trois modèles éducatifs selon les objectifs fixés : observationnel (le médecin décide), responsabilité partagée (le patient et le médecin fixent ensemble des objectifs) et autodétermination (le patient fixe ses propres objectifs).

2.3.2

Recueil des pratiques professionnelles

Le recueil des pratiques professionnelles concernant la place de l’ETP dans la prise en charge de l’escarre a été réalisé auprès d’un échantillon représentatif de participants aux congrès nationaux des quatre sociétés participantes (PERSE, SOFMER, SFGG et SFFPC) sous la forme de questionnaire ( Annexe 1 ) à choix simple ou multiple, les réponses étant enregistrées à l’aide d’un système électronique.

2.4

Résultats

2.4.1

Revue de la littérature

2.4.1.1

Recherche bibliographique

La première analyse des articles sélectionnés par l’interrogation des bases de données à partir des titres et résumés a retenu 46 articles ( Fig. 1 et Tableau 1 ). L’analyse des références a permis de rajouter deux articles supplémentaires. La seconde analyse en texte entier a exclu 41 articles. Au total, l’analyse de la littérature s’est portée sur six articles.