Volar Plate Arthroplasty

Beverlie L. Ting

Philip E. Blazar

DEFINITION

Volar plate arthroplasty (VPA) is used in the treatment of both acute and chronic dorsal fracture-dislocations of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) or distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint.8

In VPA, local tissue (volar plate) is advanced to recreate a volar restraint to dorsal subluxation/dislocation and maintain concentric reduction of the PIP or DIP joint.

VPA has also been used to treat osteoarthritis, as advanced volar plate tissue resurfaces part of the degenerative volar portion of the joint.3

ANATOMY

The volar plate is a fibrocartilaginous structure that lies palmar to both the PIP and DIP joints and is the primary restraint to hyperextension and dorsal subluxation/dislocation of these joints.2,7,9

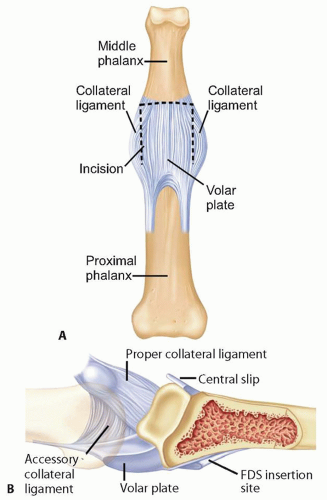

Proximally, the volar plate of the PIP joint is “swallowtail” shaped with two thickened lateral checkrein ligaments that attach to the volar periosteum of the proximal phalanx and the flexor tendon sheath (FIG 1A). A nutrient artery supplying the PIP joint emerges from the hiatus formed between the two checkrein ligaments.

Distally, the volar plate inserts centrally onto the volar periosteum and converges laterally with the collateral ligaments to form more robust attachments (FIG 1B).

The volar plate glides proximally and distally with joint motion.

The collateral ligaments originate dorsal to the interphalangeal joints and pass obliquely and volarly to their distal insertions: The proper collateral ligaments insert on the volar third of the base of the phalanx, whereas the accessory collateral ligaments insert on the lateral margin of the volar plate (see FIG 1B).

In subacute or chronic cases of dorsal joint subluxation or dislocation, these ligaments contract, thereby accentuating the deformity by virtue of their oblique orientation.

The flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) inserts just distal to the volar plate on the middle phalanx, which flexes the middle phalanx while the central slip dorsally subluxates the middle phalanx when volar restraints are lost.

PATHOGENESIS

Dorsal fracture-dislocations of the PIP and DIP are caused by hypertension or axial compression mechanisms. With hyperextension, rupture or avulsion-type injuries of the volar base of the middle phalanx occurs, whereas axial compression results in impaction or comminuted fracture patterns.

Dorsal fracture-dislocations of the PIP occur when an axial load drives the partially flexed middle phalanx into the head of the proximal phalanx, shearing the volar articular surface of the base of the middle phalanx.

Late presentation with chronic subluxation or dislocation (>6 weeks) is common, as these injuries are often misperceived as minor “sprains.”

NATURAL HISTORY

Chronic subluxation of the PIP joint leads to poor function and degenerative arthritis.

Flexion of the joint is limited and painful.

Despite optimal surgical treatment, PIP joint fracture-dislocations often result in some loss of PIP and/or DIP joint motion.

PIP joint injuries, even those that do not require surgical treatment, commonly result in a protracted period of symptoms (eg, swelling, stiffness, pain) beyond what patients expect from a “minor” injury.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

When taking the patient’s history, ask about the mechanism of injury, time since injury, any prior injuries, and the direction of deformity. Time since injury and mechanism of injury help determine the most appropriate treatment.

Inspect the finger for any swelling or deformity. Clinical deformity may be subtle, even with significant subluxation.

Examine range of motion, noting degrees of PIP motion. With joint subluxation, patients will have painful and limited flexion.

Examine joint stability; joints that are unstable will need intervention to restore stability (eg, extension block splinting, VPA).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

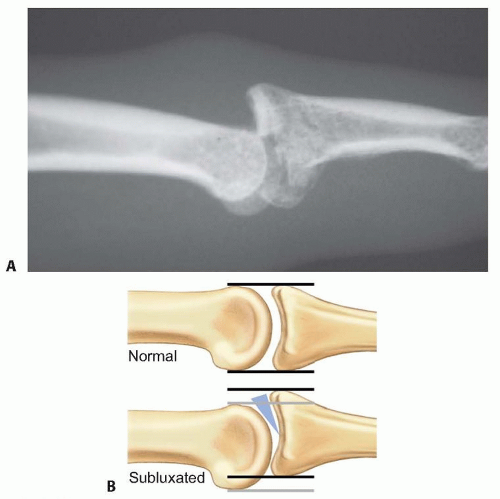

Every patient with a PIP injury must have anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs to evaluate for a PIP joint fracture or subluxation (FIG 2A).

The severity of the fracture and degree of involvement of the middle phalanx often are much greater than they appear on these radiographs.

In evaluating for a subluxation by radiographs, a true lateral view of the PIP joint is mandatory. A dorsal V sign at the joint indicates that the articular surfaces are neither congruent nor parallel (FIG 2B).

FIG 2 • A. Lateral radiograph of subluxation of the PIP joint. B. PIP joint subluxations typically display a signature dorsal V sign on the lateral radiograph, as described by Light11 (as depicted by the shaded triangle).

A lateral view is used to evaluate the percentage of articular surface involved.

Lateral views in both flexion and extension can be useful to detect hinging on the fracture margin, which can appear as normal motion on clinical examination.9

Fluoroscopy allows dynamic evaluation of the joint and its stability and often is also the best way to obtain magnified images and a perfect lateral view.

Computed tomography (CT) scans rarely are needed but can effectively evaluate the articular surfaces and define the bone loss.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Acute central slip injury (ie, boutonnière deformity)

PIP joint fracture

PIP dislocation

Volar plate or collateral ligament sprain without instability

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Closed reduction and extension block splinting are appropriate for PIP fracture-subluxations when a stable concentric joint reduction is maintained without evidence of hinging.

If more than 60 degrees of flexion is required to maintain reduction, surgical reconstruction should be strongly considered.

Articular defects will often dramatically remodel in a concentrically reduced, mobilized joint.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

For simplicity, the techniques here describe VPA for the PIP joint, but the same principles may apply to the DIP joint. The primary difference is that the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) insertion on the volar base of the distal phalanx makes exposure of the volar plate more complicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree