CHAPTER 6 Vascular assessment

Purpose of a vascular assessment

The vascular status of the lower limb bears a direct relationship to tissue viability. Furthermore, peripheral arterial disease has been shown to be associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality (Criqui et al 1992, Lange et al 2005, Leibson et al 2004). Accordingly, the assessment of the peripheral circulation may perform a useful screening function by detecting previously unidentified vascular abnormalities.

Information gained from a vascular assessment can be used to identify:

• whether the blood supply to and from a limb is adequate for normal function and tissue viability.

• vascular problems and the functional site, that is, is it an arterial venous, insufficiency or a combination lymphatic.

• whether there are any vascular abnormalities which could affect healing or the choice of treatment for another condition.

• those patients in whom vascular conditions require further investigation, treatment or referral to a specialist.

Overview of the cardiovascular system

Anatomy of the cardiovascular system

Peripheral circulation

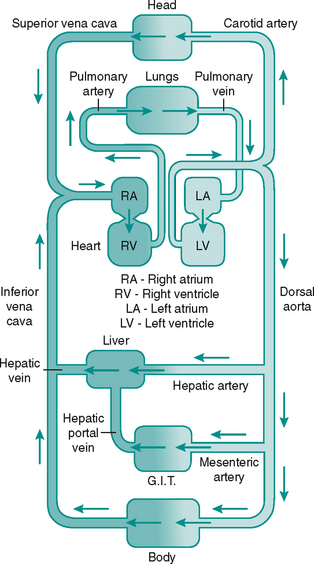

The blood flows via a system of vessels of varying diameters (Table 6.1). The major arterial and venous vessels in the lower limb are shown in Figure 6.2.

Table 6.1 Anatomy of peripheral vessels

| Vessel | Diameter | Wall thickness |

|---|---|---|

| Aorta | 25 mm | 2 mm |

| Artery | 4 mm | 1 mm |

| Arteriole | 30 μm | 20 μm |

| Capillary | 6 μm | 1 μm |

| Venule | 20 μm | 2 μm |

| Vein | 5 mm | 500 μm |

| Vena cava | 30 mm | 1.5 mm |

Arterial tree

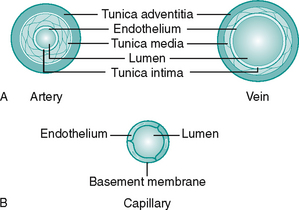

Blood is transported to the tissues is via arteries. These branch into consecutively smaller vessels called arterioles which eventually supply the capillary beds. The walls of arteries consist of three layers, from inner to outer, the tunica intima, tunica media and tunica adventitia (Fig. 6.3A). The interface of the vessel with the streaming blood is lined with endothelial cells to form a smooth surface to prevent adhesion of blood components. These cells secrete a variety of substances essential for maintenance of the vessel wall and circulatory function. All the vessels have some smooth muscle in the tunica media to enable them to change diameter, but arterioles have the greater proportion (primarily under sympathetic control).

Venous tree

Blood is drained from the tissue beds by venules, which join to form the veins, a system with larger capacitance than the arteries. The three layers seen in the arterial wall are also present in veins but the proportions differ, as can be seen in Figure 6.3A. Veins are found either in the superficial fascia or deep to the muscle. Communicating veins allow drainage from the superficial to deep veins. The vascular endothelium is specialised to form semilunar valves. These prevent backflow of blood and are especially important in the perforating veins. The systemic veins of the lower limb drain into the inferior vena cava and return the deoxygenated blood back to the heart.

Capillary bed

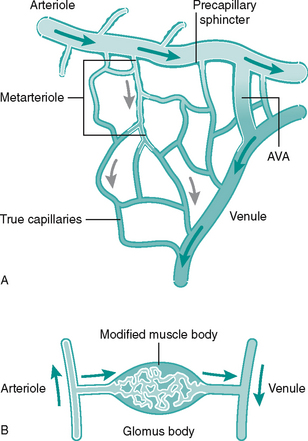

Networks of capillaries link the arterioles and venules. They are the smallest and most numerous vessel, having only a thin-walled endothelium (Fig. 6.3B). Capillaries facilitate delivery of oxygen and nutrients to local tissues and no cell is far from a capillary bed. Precapillary sphincters in short vessels called metarterioles control capillary bed perfusion. Capillaries can be bypassed by arteriovenous (AV) anastomoses or ‘shunts’ which are vessels forming a direct link between an arteriole and a venule (Fig. 6.4A). At cutaneous sites exposed to extremes of temperature, such as fingertips, apices of toes, nose and earlobes, the AV anastomoses are numerous and form specialised structures under the nail beds called glomus bodies or Sucquet–Hoyer canals (Fig. 6.4B). Shunting of blood from the superficial to deep, thus bypassing cutaneous regions, helps to preserve core body temperature.

Tissue fluid

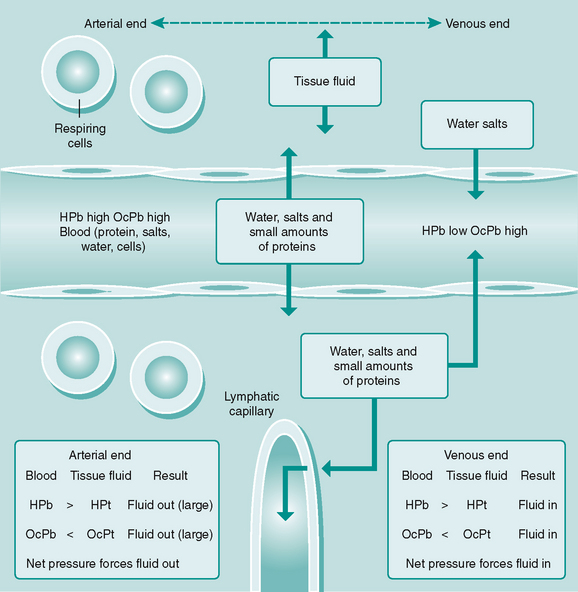

While capillaries bring blood close to all body cells, a diffusion medium is needed to enable nutrients, waste products and gases to be exchanged between the cells and the blood and lymph. This medium is tissue fluid, which is continuously forming from blood at capillary and postcapillary venular sites as a result of hydrostatic and oncotic pressures (Fig. 6.5). Some tissue fluid is reabsorbed back into these vessels, the remainder draining into the lymphatic capillaries to be returned to the general circulation.

The vascular assessment

![]() The assessment of each part of the vascular tree includes the following:

The assessment of each part of the vascular tree includes the following:

General overview of the cardiovascular system

Central problems such as congestive heart failure, ischaemic heart disease (angina and/or myocardial infarction), as well as systemic problems such as the anaemias may all influence the circulation to and from the lower limb (Box 6.1).

Box 6.1 Cardiac conditions which may affect lower limb perfusion

History and medication

History taking is discussed in detail in Chapter 5. Any factors which compromise tissue perfusion will deprive the tissue of not only oxygen but also nutrients and prevent removal of waste products. This causes hypoxia to the associated tissues, referred to clinically as ischaemia. The most common cause of ischaemia is atherosclerosis and associated complications, which produce ischaemic heart disease (IHD) (coronary vessels), cerebrovascular accidents (cerebral vessels) and peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Atherosclerosis is predominantly a disease of large and medium-sized arterial vessels, although the distribution and progression of atherosclerotic disease is different in the diabetic population, with some small arteries affected (Aboyans et al 2006). Prognosis is thought to rely more on the predisposition of plaque erosion and/or rupture, than on the extent of atheromatous disease (Falk et al 1995, Libby 2001).

The presence of atheromatous disease anywhere in the body should alert the clinician to consider atherosclerosis in other areas, that is, the presence of angina may predict atherosclerosis in the vessels supplying the lower limb (Fisicaro 2003). The segments between the descending aorta and the popliteal artery are most likely to develop such disease. Below the level of the knee, the vessels are small arteries, which are generally not affected by clinically relevant atherosclerosis in the non-diabetic population. However, the majority of studies performed have been in the Caucasian population, and an extensive review of PAD and ethnicity indicated that prevalence of more distal disease may occur in black and Asian populations (Hobbs et al 2003).

The medical history enquiry should elicit information regarding IHD, as well as the presence of risk factors for atherosclerosis, such as smoking, hypertension or dyslipidaemia (Case history 6.1). Primary diabetes mellitus is strongly associated with earlier and more advanced atherosclerosis (Kallio et al 2003). The surgical history enquiry should include any intervention to cardiovascular structures, for example angioplasties (coronary, iliac, etc.), bypass surgeries and vein operations, for example sclerosis or stripping of veins.

Relevant social history includes smoking, alcohol, lifestyle, psychosocial stresses and socioeconomic circumstances. Smoking has numerous deleterious effects on blood vessels with the mechanism of action(s) not yet fully understood. Pathologies include increased platelet adhesion, endothelial lining damage, increased vasoconstriction and reduced antioxidant plasma levels and reduced fibrinolysis (Newby et al 2001, Tsuchiya et al 2002). Moreover, there may be damage to the endothelial lining by passive smoking as well (Barnoya & Glantz 2005, Otsuka et al 2001), therefore close contact with a smoker and occupation may be pertinent.

The effects of alcohol intake on circulation are less clear. Moderate drinking is associated with a lowered cardiovascular mortality (Mukamal et al 2005) for both genders, possibly linked to an anti-inflammatory effect (Albert et al 2003). However, a high intake has been linked to increased risk, associated with impaired fibrinolysis (Mukamal 2001). Lifestyle factors such as diet (e.g. salt, fat intake), exercise, occupation and stress levels should help form a picture of general mental and physical health, mobility and risk levels. Socioeconomic risk factors for cardiovascular disease include low socioeconomic status (Steptoe et al 2002) and low education levels (Grazuleviciene et al 2002).

Drugs may indicate cardiovascular disease is present (e.g. diuretic therapy), or influence circulation as a side effect. Many of the antihypertensive drug regimens such as diuretics, beta-blockers and calcium antagonists can affect the peripheral circulation. Diuretics act on various parts of the nephron in the kidney to reduce water and salt reabsorption, initially reducing preload and cardiac output and later affecting peripheral resistance, with both mechanisms reducing blood pressure. Beta-blockers prevent the stimulatory action of endogenous catecholamines on the heart, again reducing cardiac output and blood pressure. Even selective agents, such as atenolol, may cause some peripheral vasoconstriction. Calcium antagonists act by interfering with the process of vascular smooth muscle contraction, reducing peripheral resistance and so reducing blood pressure. Some act more peripherally than centrally, for example amlodipine and have some vasodilatory influence (currently not licensed for PAD).

Lipid-lowering drugs indicate risk factors for thrombotic disease, given the relationship between dyslipidaemia (high low-density lipoprotein (LDL), low high-density lipoprotein (HDL), high triglycerides, low apolipoproteins) formation of atheroma and cardiovascular disease (Hobbs 2003). The most common are the statin and fibrate drug groups. Anti-platelet drugs are most commonly taken for IHD (to prevent and/or to manage), and are also used for management of transient ischaemic attacks, stroke, PAD, and after some vascular surgeries e.g. angioplasty stunt. Taking an anti-platelet indicates risk of, or the presence of thrombotic disease and should alert the clinician to enquire about the nature of the problem. The most common drug is aspirin, but clopidogrel and dipyridamole are also used. Anticoagulation therapy, usually warfarin (non-acute), indicates cardiovascular disease such as atrial fibrillation, valve disease/replacement, history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, and it is sometimes used for the management of stroke.

Central symptoms

Angina and myocardial infarction (MI)

The chief distinguishing feature of an acute MI, as opposed to an angina pectoris attack is that the latter lasts only minutes and is usually relieved within 5 minutes of rest or by sublingual glyceryl trinitrate. There are many other causes of chest pain and while few closely mimic angina, indigestion and other gastrointestinal disorders may be confused with angina (Ch. 5). It is noteworthy that diabetic autonomic neuropathy, as well as age can mask symptoms of IHD, and silent heart attacks do occur (Fornengo et al 2006).

Signs

Pallor

A pale appearance, noticeable in the face, palmar or plantar areas, the conjunctiva or nail bed may indicate anaemia, but this is not a sensitive observation (Nardone et al 1990).

The nails

Iron-deficiency anaemia may cause koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails), a sign also associated with connective tissue disease (Fawcett et al 2004). Clubbing of the finger nails may be due to subacute infective endocarditis or congenital cyanotic heart disease. It is also associated with a variety of other, primarily respiratory causes (Fawcett et al 2004). Splinter haemorrhages appear as subungual small brown/black splinters and can be associated with vasculitis (inflammation of a blood vessel(s)), although trauma is a common cause. If pathological, a local cause such as a digital septic thrombosis should be considered, as should widespread involvement of arteries of all organs, including coronary, splanchnic and cerebral, which can occur, for example in aggressive rheumatoid arthritis. Splinter haemorrhages may also indicate subacute bacterial endocarditis (Fawcett et al 2004).

Clinical tests

Heart rate and rhythm

Heart rate and rhythm are normally assessed by taking the pulse at the wrist (radial artery), with a normal adult resting rate at between 60 and 80 beats per minute. Arrhythmias are abnormal heart rates/rhythms and can be physiological or pathological, depending on the cause. A change in pace, but where sinus rhythm is sustained, may reflect a physiological response by the pacemaker for the heart, the sinoatrial node. Heart rates of less than 60 beats per minute are classified as bradycardia and those over 100 beats per minute as tachycardia. Athletes are an example of physiological bradycardia, whereas the bradycardia due to a complete heart block in the atrioventricular septum is pathological. Thyroid hormones, if present in excess, increase the affinity of beta1-receptors to catecholamines and so induce tachycardia, as seen in hyperthyroidism. Rhythm is denoted as regularly regular (sinus rhythm), regularly irregular (a repeating irregularity, for example ectopic beats) or irregularly irregular, for example atrial fibrillation.

Blood pressure

Manual (see Box 6.2) or automated equipment may be used to obtain readings, with equally good repeatability, but with the precaution that differences in readings between devices may seem clinically relevant (Sims et al 2005). The British Hypertension Society recommend several readings are taken before ‘persistent’ high blood pressure is diagnosed. It is now commonplace for people to monitor their own blood pressure at home or have ambulatory blood pressure monitoring via a 24 hour tape, thus obtaining a more accurate mean value taken over 24 hours. The upper normal limit is lower in children and higher in elderly people. Assessment also includes determination of risk factors e.g. bodyweight, salt intake etc.

Box 6.2 Taking blood pressure – manual technique

• The brachial pulse should be palpated.

• A sphygmomanometer cuff is wrapped around the arm, 2–3 cm above the elbow crease.

• The pressure cuff should be inflated until the brachial pulse can no longer be palpated. The value of this pressure should be noted and the pressure released rapidly.*

• The diaphragm of the stethoscope is placed on the brachial artery in the antecubital fossa and the pressure cuff re-inflated to the same value as previously obtained. Nothing will be heard at this stage. All vessels will be occluded so that no blood can flow through the artery.

• The pressure should be released slowly and steadily (2 mm/s), watching the needle on the manometer face. As the pressure falls to the level of the patient’s systolic blood pressure a knocking sound will be heard in the stethoscope. At this stage the pressure in the cuff is sufficient to prevent flow of blood during diastole, but not during systole, so that systolic flow can be heard. The value when the first sound returns is recorded as the systolic blood pressure.

• The pressure should continue to be released. The sounds will first increase then decrease in intensity and finally disappear. At this stage the pressure in the cuff is insufficient to occlude the artery at any stage in the cardiac cycle and this point is taken as the value for the diastolic blood pressure.

• The practitioner should ensure that the cuff is deflated completely.

Peripheral vascular system

Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) in the singular is often taken to mean the manifestations of atherosclerosis distal to the aortic arch. PAD or peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) are more accurate terms. The plural term peripheral vascular diseases refers to all anatomically relevant vascular pathologies. It is important to distinguish between an impoverished arterial supply, reduced venous drainage and impaired lymphatic drainage, although more than one pathology may be present.

Many authors have emphasised the central role of the clinical examination, which when performed competently, can provide information both sensitive and specific for PAD diagnoses (Boyko et al 1997, Criqui et al 1992). Of the non-invasive tests, the ABPI remains the global gold standard (Collins et al 2006, Hiatt et al 1995, Hirsch et al 2001, McDermott et al 2000, Newman et al 1993). Invasive tests are usually reserved for presurgical evaluation. The non-invasive assessment yields information to help confirm the presence of PAD, determine the extent and distribution of stenoses, monitor changes following interventions and/or over time, and make clinical judgements regarding healing potential. Despite the poor prognostic outlook and the plethora of clinical methods applied to PAD assessment, it remains under-diagnosed (Hirsch et al 2001).

One of the most important indicators for undertaking an assessment of lower limb circulation is the condition of diabetes mellitus. While the approach is broadly the same, it has been demonstrated that the reliability of key tests such as the ABPI, the toe brachial index and pulse waveform analysis may be compromised, particularly in the presence of diabetic neuropathy (Williams et al 2005). This will influence the interpretation of the test results.

Arterial insufficiency

Medical history

Conditions which can affect the arterial supply to the lower limb can be viewed as acute, chronic or transient (Table 6.2). Most arterial problems affecting the lower limb are chronic and involve the progressive narrowing of peripheral arteries, most commonly the aortoiliac bifurcation and the iliac segments. While this can result in claudication pain and to varying degrees poor tissue viability, only a small percentage of people (1–6% in 5 years, rising to 18% in 10 years) require surgery (Andreozzi & Martini 2004). Up to 5% develop critical ischaemia requiring amputation (Dormandy et al 1989, McDaniel & Cronenwett 1989), although this figure may double over 10 years (Andreozzi & Martini 2004). Age-related and generalised vessel disease is referred to as arteriosclerosis, involving thickening and hardening of the vessel wall.

Table 6.2 Causes of arterial insufficiency in the foot

| Acute | |

| Transient (usually lead to acute problems but may progress to chronic) | |

| Chronic |

The most common cause of PAD is atherosclerosis. This is a pathological process involving formation of a fatty plaque (atheroma) in the subintimal space of large and medium-sized arteries (Murphie 2001a). The atheroma itself may protrude into the lumen and reduce or obstruct flow. However, the greatest risk arises from predisposition of the overlying fibrous cap to ulcerate, promoting thrombus formation. This may cause further narrowing (stenosis) or even complete blockage of the vessel. In addition, fragments of the thrombus can embolise and be swept away, causing obstruction further down the arterial tree. Global risk factors for systemic atherosclerosis are similar and recognised in descending order as hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and diabetes, with obesity and tobacco usage being other key factors (Bhatt et al 2006). A clinical history that indicates atherosclerotic complications assists in the assessment of vascular health. Angina, MI and coronary or peripheral bypass surgery all indicate the extent and stage of atherosclerotic disease. Aneurysm must also be taken into consideration, as the most frequent underlying pathology is atherosclerosis (Fig. 6.6). Furthermore, an association exists between aortic and popliteal aneurysms, so this must always be checked.

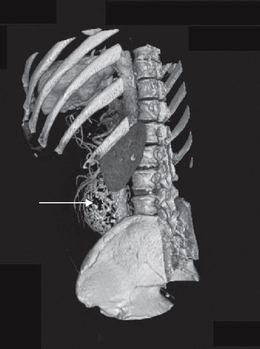

The clinician should be aware of pathological vascular calcification, as high levels in coronary vessels are linked to an increased risk of sudden death and MI (Greenland et al 2004, O’Rourke et al 2000). The clinical relevance in the lower limbs is poorly understood, but there are implications for test selection (see the sections on ABPI and toe pressures) and management of vasculopathies. Vessel wall calcification (Fig. 6.7) is most commonly seen in advanced atherosclerotic plaques, giving the ‘sclerotic’ or hardening component of the plaque in the subintimal space. The resulting rigidity will alter vascular resistance and elasticity. Normally mechanisms are in place to prevent abnormal calcium deposition in non-osseous tissues, for example via protective matrix proteins such as osteopontin. More research is needed to discover the pathogenesis of calcific damage.

A distinct process of dystrophic calcification can affect the smooth muscle layer of the vessel wall, often referred to as medial arterial calcification or Mönckeberg’s sclerosis. The condition is associated with atrophy of the smooth muscle arising from autonomic neuropathy (Forst et al 1995, Gilbey et al 1989) and it follows that this is seen with age (Elliott & McGrath 1994) and diabetes (Chantelau et al 1997, Edmonds 2000, Watkins & Edmonds 1983). It generally affects arteries not associated with atherosclerosis, for example distal small arteries (Figs 6.7, 6.8) and breast and thyroid vessels, although it is found in the aorta. One study on a population of people with type 2 diabetes found medial sclerosis in 17% and intimal-type calcifications in 23% (Niskanen et al 1994). The calcium deposits are laid down upon the circumferential smooth muscle and it is this process which is attributed to non-compressible vessels in the diabetic population (Edmonds et al 1982). Atherosclerotic and medial wall calcification may coexist and both contribute to rigid and inelastic vessel walls.

Primary diabetes mellitus has deleterious effects on arteries, accelerating the atherosclerotic process and worsening the prognosis for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Kallio et al 2003). PAD is twice as likely to occur in the diabetic population (Wattanakit et al 2005). Amputation rates (Aksoy et al 2004, McAlpine et al 2005) and mortality associated with PAD are also increased (Leibson et al 2004). The pattern of diabetic atherosclerotic lesions varies from the non-diabetic population, in that extensive involvement of vessel segments is seen, as well as more distal occlusions, for example the posterior tibial artery (van der Feen et al 2002). Such multilevel disease not only has implications for tissue viability but also presents major problems for management (Faries et al 2001).

Renal disease has a number of effects on blood vessels and as a frequent complication of diabetes mellitus, kidney disease poses an additional threat to peripheral perfusion and tissue viability when these coexist. Medial arterial calcification is accelerated with significant renal disease (Leskinen et al 2002) and this is likely to be related to failure of calcium and phosphate regulation. Impaired vitamin D conversion and hyperparathyroidism will also contribute to disturbed mineral metabolism.

There appears to be little evidence for atherosclerosis in the microcirculation (Murphie 2001b). Although hyalinisation (arteriolosclerosis), thickening of basement membranes and functional abnormalities of small vessels have been observed, these changes occur mainly in renal and retinal vessels, and are not considered to have major effects on the vascular status of the foot. However, in the diabetic population, there has been considerable focus on abnormalities of the microcirculation, since this is suspected to contribute to the non-healing wound.

Raynaud’s disease and phenomenon (when linked to another disease) affects approximately 5% of the population and, in severe cases, may produce digital atrophy, necrosis and ulceration (Case history 6.2). Chilblains are also thought to rise from increased vasoreactivity to non-freezing cold. Arterial emboli can be composed of any obstructive body that lodges in the smaller vessels of the arterial tree, causing ischaemia distally. The most common embolus is formed by a thrombus fragment, for example from the heart during atrial fibrillation, from an aortic aneurysm or following an MI. Where smaller arteries branch or narrow, impaction occurs and in the lower limb, vulnerable sites include the common femoral bifurcation and the popliteal trifurcation.

Symptoms

An acute occlusion, for example femoral embolism, produces signs and symptoms known as the six Ps:

If the occlusion is prolonged (more than 6–8 hours), the tissues eventually suffer irreversible damage and this stage can be recognised by mottling, muscle tenderness, motor or sensory deficit and necrosis. Prompt embolectomy is required for limb salvage. Amputation may be required (Campbell et al 1998). Rarely, fat emboli may lodge in small/microvascular peripheral vessels causing vasculitis and necrosis, for example following vascular surgery. This can be seen in the foot.

Chronic PAD may share some of these signs and symptoms and certainly pain on walking (see intermittent claudication), at rest (see rest pain) and in the extremities, can arise from chronic ischaemia. However, PAD is asymptomatic in 80–93% of cases (Fowkes et al 1991, Newman et al 1993), with smoking and diabetes mellitus associated with a higher probability of symptom absence (Eason et al 2005). Pain may develop suddenly following thrombosis overlying a plaque, but if atherosclerosis has been present long-term, symptoms may be less severe than for an acute embolism, since collateral vessels will have formed. The following types of ischaemic pain can occur (also see Fontaine’s classification (Table 6.3)).

Table 6.3 Fontaine’s classification of peripheral vascular disease

| Stage | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 1 | Occlusive arterial disease but no symptoms (due to collaterals) |

| 2 | Intermittent claudication |

| 3 | Ischaemic rest pain (usually worse at night, relieved by dependency) |

| 4 | Severe rest pain with ulceration/necrosis (gangrene) |

Intermittent claudication

Just as angina pectoris indicates insufficient blood supply to the myocardium, so intermittent claudication indicates inadequate blood supply to the periphery. The deficiency will be accentuated on exercise, occurring at a reproducible distance (the claudication distance) with a characteristic cramping or aching pain. Sometimes the complaint will be tightness, fatigue or burning in the affected muscle group. The exercising muscles have to respire anaerobically and produce metabolites which are not cleared by the blood. These cause ischaemic pain, which forces the patient to stop the activity. Resting for a few minutes reduces the amount of metabolites produced and allows the patient to continue walking for a further period. It is typical of claudication pain to subside within 10 minutes of rest. The distance walked before onset of the pain is a good indication of the severity of the condition, which may affect mobility and quality of life (Dumville et al 2004). Accurate assessment and diagnosis of claudication may be achieved using the Edinburgh claudication questionnaire (Leng & Fowkes 1992), which has a high sensitivity and specificity of 91% and 99%, respectively.

The region of the ischaemic muscle pain can indicate the site of the occlusion (see Box 6.3), with symptoms typically one level below the constriction. Calf pain is common (Buckenham 2003), with thigh, hip, and buttocks affected when more extensive proximal lesions are involved. Non-arterial sources of pain should be considered, for example arthritis, degenerative spinal disease, not only as part of the differential diagnoses but also because such conditions may mask the presence of symptomatic PAD (Newman et al 2001). It should be borne in mind that patients with neuropathy may not complain of intermittent claudication.

Box 6.3 PAD distribution according to claudication symptoms

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree