Valgus Osteotomy of the Proximal Femur

Wudbhav N. Sankar

DEFINITION

Valgus osteotomy of the proximal femur can be performed for a number of different conditions including (among others) congenital or acquired coxa vara, fracture nonunion, avascular necrosis (AVN), or Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD).

Coxa vara is a deformity of the proximal femur associated with a neck-shaft angle of less than 110 degrees.11 It can be congenital or developmental in origin.

Femoral neck fracture nonunions can result (in part) from a vertically oriented fracture plane. A valgus osteotomy can improve mechanical loading at the fracture site and aid in fracture healing.

AVN of the femoral head typically affects the anterosuperior region of the femoral head while sparing the medial and posterior regions. In certain cases, a valgus osteotomy (with flexion) can rotate better parts of the femoral head into the weight-bearing zone.

In LCPD, valgus osteotomy can help those hips in which the primary goal of containment is no longer possible owing to hinge abduction. Under these circumstances, a valgus osteotomy can relieve the hinging and improve congruency of the joint.

ANATOMY

Valgus osteotomy creates an apex medial angulation in the proximal femur.

In doing so, the medial aspects of the femoral head are rotated more centrally into the joint and, correspondingly, the lateral aspects of the head are rotated away from the joint.

Adding flexion or extension at the osteotomy site similarly rotates the posterior (flexion) or anterior (extension) aspects of the femoral head into the joint.

Valgus osteotomy increases a patient’s effective hip abduction by the amount of correction and similarly reduces the patient’s adduction by an equivalent amount.

Length of the limb is increased by a valgus correction, which can be useful in cases of mild limb shortening (eg, LCPD).

Valgus correction moves the greater trochanter distally, which improves abductor mechanics.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of the deformity to be treated by valgus osteotomy is specific to the underlying condition.

The exact cause of developmental coxa vara is unknown, but one theory postulates that the varus deformity is due to a primary ossification defect in the medial femoral neck that results in a more vertical physis. The physiologic shearing stresses that occur during weight bearing fatigue the dystrophic bone in the medial femoral neck, resulting in progressive varus.7

AVN of the femoral head is the final common pathway of a spectrum of disease processes that disrupt circulation to the femoral head including embolism from deep sea diving, alcohol use, corticosteroid use, hemoglobinopathies, chemotherapy, LCPD, and traumatic injuries to the hip.1

Hinge abduction in LCPD can result from fragmentation and extrusion of the epiphysis, which can create coxa magna and/or a ridge of lateral bone. As a result, the lateral aspect of the deformed femoral head may impinge on the acetabulum with attempted abduction. Continued abduction creates a lateral hinge, which pulls the inferomedial portion of the head away from the acetabulum.8

NATURAL HISTORY

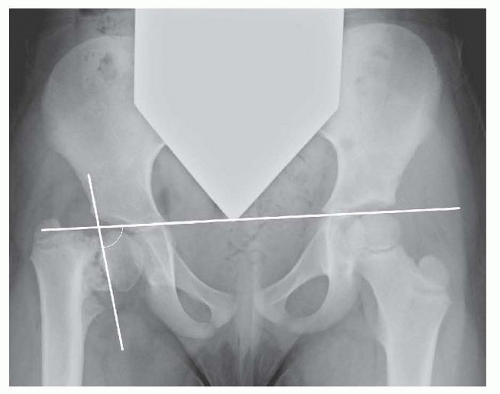

As described by Weinstein et al,11 the most reliable factor for progression of coxa vara is the Hilgenreiner-epiphyseal angle (HEA), measured between the line of Hilgenreiner and a line parallel to the proximal femoral physis (FIG 1).

Patients with HEAs more than 60 degrees will invariably progress, whereas those between 45 and 60 degrees have a less defined prognosis and must be followed for progression of varus deformity or increased symptoms.

AVN of femoral head typically results in progressive collapse, pain, and stiffness often necessitating total hip arthroplasty.1

At maturity, patients with LCPD and unrelieved hinge abduction would generally be classified as Stulberg category IV

(flattened femoral head with congruent acetabulum) or category V (flattened femoral head with a round acetabulum), both of which have been found to be associated with early-onset osteoarthritis.10

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

History and physical findings are specific to the underlying condition.

Typically, patients who would benefit from a valgus osteotomy have pain with ambulation that is relieved by rest.

There is generally 1 to 2 cm of limb shortening.

Abductor weakness often causes a Trendelenburg gait.

Limited abduction is common, and occasionally, patients have frank adduction contractures.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs are generally diagnostic for the conditions that may require a valgus osteotomy.

Anteroposterior (AP) x-rays of the hip in coxa vara will demonstrate a reduced neck-shaft angle and a wider more vertically oriented proximal femoral physis. Classically, a triangular metaphyseal fragment will be seen in the inferior neck surrounded by physis, giving an inverted Y pattern11 (see FIG 1).

Femoral neck nonunions typically result in medial collapse and varus deformity. Subtle nonunions can be confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scan.

On the AP view, AVN typically results in sclerosis and/or collapse of the lateral and superior regions of the femoral head. On the frog view, the anterior head is more commonly affected.

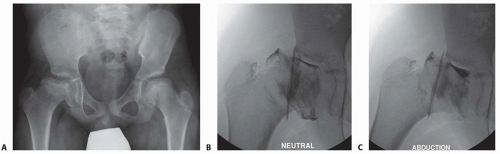

Hinge abduction in LCPD is best diagnosed using dynamic arthrography. Although pooling of dye medially is often considered diagnostic for hinge abduction, this can simply reflect an area of flattening of the epiphysis. It is most accurate to determine whether the lateral edge of the femoral head is able to rotate underneath the lip of the acetabulum and labrum with abduction (FIG 2). Congruency is generally improved when the hip is adducted.

The arthrogram should also be studied in AP and lateral projections with abduction, adduction, and internal and external rotation to determine the position that maximizes congruency and relieves impingement.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Congenital or acquired coxa vara

Femoral neck nonunion

AVN

LCPD with hinge abduction or poor congruency

Pathologic bone condition causing progressive varus deformity (eg, fibrous dysplasia, osteogenesis imperfecta, renal osteodystrophy)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Mild forms of coxa vara, precollapse AVN, and early-stage LCPD may be managed conservatively.

Depending on the circumstance, short courses of antiinflammatory medications, protected weight bearing, and/or activity modification can be helpful.

In LCPD, if hinge abduction is seen on radiographs but the patient is symptom-free, an osteotomy can still improve the prognosis. In that scenario, it would be reasonable to wait until the patient is symptomatic before proceeding with surgery.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The valgus osteotomy is indicated for unacceptable varus deformity, fracture nonunion, and certain cases of AVN among others.

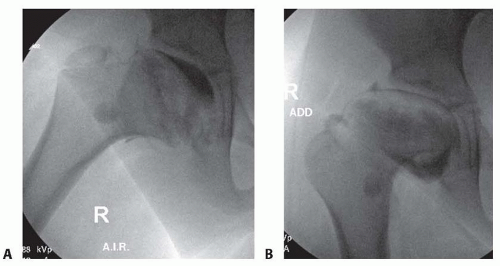

In LCPD, valgus osteotomy is considered a salvage operation for late cases in which the femoral head has developed a lateral ridge that can no longer be brought under the acetabulum (hinge abduction) or to improve congruency of an aspherical hip (FIG 3).

Preoperative Planning

Clinically or radiographically assess limb lengths to determine if concomitant shortening is necessary.

Carefully evaluate preoperative range of motion including flexion, extension, and rotation.

Specifically evaluate a patient’s adduction and abduction prior to surgery to guide the amount of correction. Keep in

mind that adduction will be decreased and abduction will be increased by the amount of osteotomy correction. Generally, it is preferable to achieve at least 20 degrees of abduction after surgery.

FIG 3 • A. Arthrogram of the hip in a patient with healed LCPD. Note the poor congruence in the neutral position. B. Congruence is improved when the hip is adducted.

If an arthrogram was performed, it should be reviewed carefully. In cases of hinge abduction, extension, flexion, or rotation may be required in addition to valgus to fully relieve impingement and maximize congruency.

Review preoperative AP and frog lateral radiographs to determine the native neck-shaft angle and size of bone.

Based on range-of-motion measurements and preoperative radiographs, one should determine the desired amount of valgus correction.

Implant choice is critical as the placement and shape of the implant, rather than the saw cut, will determine the final position of the osteotomy.

The author prefers a 130-degree nonoffset blade plate, which lateralizes the femoral shaft and preserves head-shaft offset (FIG 4A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree