Chapter 213 Vaginitis

General Considerations

General Considerations

In addition to causing physical discomfort and embarrassment, vaginitis is medically important for several reasons. It may coexist with cervicitis and may be related to a sexually transmitted infection; some of these organisms may be able to ascend and cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID may in turn lead to tubal scarring, infertility, or ectopic pregnancy. Chronic asymptomatic vaginal infections have been implicated in recurrent urinary tract infections through their action as reservoirs of the infectious agent.1,2 Some types of vaginal infections, such as bacterial vaginitis (BV) during pregnancy, are associated with preterm delivery, premature rupture of membranes, amnionitis, chorioamnionitis, and postpartum endometritis; if present at delivery, they may be associated with an increased incidence of neonatal infection, with potentially serious or fatal consequences.

The vaginal ecosystem is an environment consisting of an important relationship between normal endogenous microflora, metabolic products of the microflora and the host, estrogen, and the pH level. The normal microflora of a healthy vagina is made up of numerous microorganisms, including Candida, Lactobacillus species, gram-negative aerobic bacteria, and facultative organisms (Mycoplasma species and Gardnerella vaginalis) as well as obligate anaerobic bacteria (primarily Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus species, Eubacterium species, and Mobiluncus). Lactobacillus species dominate the healthy vagina of a reproductive-age woman, and although it is difficult to say with certainty which species are most common, molecular biology methods and at least one study have found that Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus rheuteri, and Lactobacillus acidophilus are the most often present.3 Yet another study has found that the most frequent Lactobacillius species were L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. jensenii, and L. rhamnosus.4

The normal microflora of the vagina, dominated by lactobacilli, is capable of inhibiting the adhesion and growth of pathogens; it depletes nutrients available to pathogens and modulates the host immune response and vaginal environment.5,6 Lactobacilli act via at least three mechanisms: (1) they help to produce lactic acid and other acids as a by-product of glycogen metabolism in the vaginal vault cells and provide a normal vaginal acidic environment of 3.5 to 4.5. Many pathologic microbes cannot survive or flourish in this pH. (2) Many species of lactobacilli produce hydrogen peroxide, which also inhibits microbial growth. (3) The lactobacilli are competitive with the pathogenic microorganisms for adherence to the vaginal epithelial cells.

Types of Vaginitis

Types of Vaginitis

Vaginitis is commonly classified as being caused by yeast, bacterial vaginosis (BV), Trichomonas vaginalis, or atrophic vaginitis. However, these traditional classifications have left gaps in the proper diagnosis and treatment of several atypical scenarios of vaginitis. Experts in this field have proposed three additional categories, which include desquamative vaginitis (DIV), Mobiluncus vaginitis and lactobacillosis. Even with the addition of these three categories, there still appear to be two patterns of altered flora in symptomatic women that do not fall into any of the other designated categories. Stuart Fowler of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona, had proposed two additional categories of altered flora: the first he describes as noninflammatory vaginitis (NV) and the second as inflammatory vaginitis (IV). With the recognition of these two patterns of altered flora, clinical presentations that do not fit the usual criteria for the diagnosis of BV, Trichomonas, Candida, atrophic vaginitis, DIV or lactobacillosis can now be recognized and treated. Details regarding these additional types of vaginitis can be found in Fowler’s published paper.7

Infectious Vaginitis

Infectious vaginitis (e.g., trichomoniasis) may be sexually transmitted or may arise from a disturbance to the delicate ecology of the healthy vagina (e.g., Candida and BV). Vaginal “infections” frequently involve common organisms found in the cervix and vagina of many healthy asymptomatic women.8

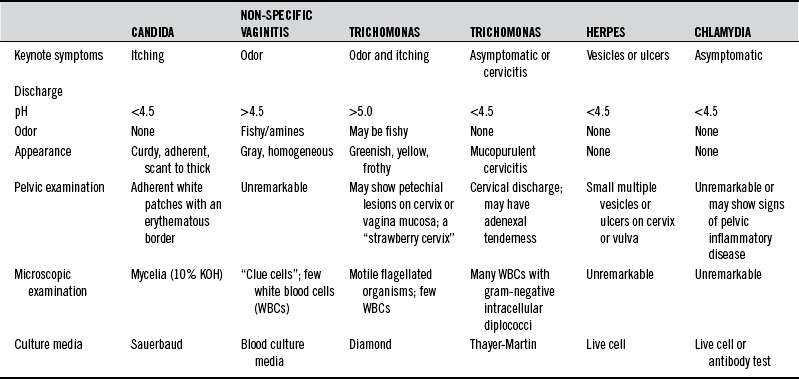

Predisposing factors for sexually transmitted infections include a higher number of sex partners, unsafe sex, birth control pills, steroids, antibiotics, tight-fitting garments, occlusive materials, douches, chlorinated pools, perfumed toilet paper, and decreased levels of lactobacilli in the vagina. Table 213-1 summarizes the diagnostic differentiation of the most common causes of infectious vaginitis.

Trichomonas vaginalis

Trichomonas vaginalis is a flagellated protozoan slightly larger than a leukocyte. It may be found in the lower urogenital tract of both men and women. Humans appear to be its only host, and sexual transmission appears to be its primary mode of dissemination. Trichomonas does not invade tissues and rarely causes serious complications. The most common symptom is leukorrhea associated with itching and burning. The discharge is frequently malodorous, greenish yellow, and frothy. The “strawberry cervix” with punctate hemorrhages is found in only a small percentage of patients with Trichomonas infection. Trichomonads grow optimally at a pH of 5.5 to 5.8.9 Thus, conditions that elevate the pH, such as increased progesterone, will favor overgrowth of Trichomonas. Conversely, a vaginal pH of 4.5 in a woman with vaginitis is suggestive of an agent other than Trichomonas. A saline wet mount of fresh vaginal fluid demonstrates the presence of small motile organisms to confirm the diagnosis in 80% to 90% of symptomatic carriers.10,11

Candida albicans

Both the relative frequency and the total incidence of candidal vaginitis have risen dramatically, 2.5-fold, in the past 20 years. This increase parallels a declining incidence of gonorrhea and trichomoniasis.12 Several factors have contributed to this increased incidence, chief among them being the greater use of antibiotics. The alterations that antibiotics make in both intestinal and vaginal ecology favor the growth of Candida. In the 1970s, Miles et al11 found a 100% correlation between genital and gastrointestinal Candida cultures, leading to the suggestion that significant intestinal colonization with Candida may be the single most significant predisposing factor in vulvovaginal candidiasis. However, this suggestion has not been confirmed by adequate research.

Steroids, oral contraceptives, and the continuing rise in incidence of diabetes mellitus all contribute to the problem. Candida is 10 to 20 times more common during pregnancy owing to the elevated vaginal pH, increased vaginal epithelial glycogen, elevated blood glucose, and intermittent glycosuria. Yeast infections are three times more prevalent in women wearing pantyhose than those wearing cotton underwear because the pantyhose prevent drying of the area.13

A woman who has four or more episodes of vulvovaginal candidiasis within 1 year is classified as having recurrent disease. Many cases of recurrent yeast infections may be caused by non-albicans strains of Candida. These resistant strains have become more problematic in recent years as women have been using more and more antifungal agents (see Box 213-1). There are three main theories to explain why women have recurring yeast vaginitis: (1) the intestinal reservoir theory, which hypothesizes that a patient’s reinoculation is due to Candida populating in the gastrointestinal tract and migrating into the vagina; (2) the sexual transmission theory, which points to the possibility that the sex partner is the source of the recurrence; and (3) the vaginal relapse theory, which maintains that some women retain small numbers of yeasts, even after treatment, that later cause a resurgence of symptoms. A considerable body of research supports this last theory.14,15 These studies include immunologic research suggesting that women with recurrent infections have an abnormal immune response to infection, which leaves them susceptible to further episodes.16

Bacterial Vaginosis

Three main factors have been identified to explain how the shift from a lactobacilli-dominant environment to one in which the anaerobes and facultative bacteria dominate and therefore why some women experience BV—sexual activity, douching, and the absence of peroxide-producing lactobacilli in the vagina. A new sex partner and frequent sexual activity are associated with an increased incidence of BV. Overall, sexual transmission of BV is not well understood. It may not be truly sexually transmitted but rather may occur by various mechanisms other than the sexual transmission of pathogens. Routine douching is associated with a loss of vaginal lactobacilli and the occurrence of BV. Women who douche regularly have BV twice as often as women who do not.17 It is possible that women with an absence of peroxide-producing lactobacilli in the vagina did not have the normal inhabitation of lactobacilli at menarche, or perhaps the lactobacilli were present but were eliminated through the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Other factors have been associated with the development of BV. Cigarette smoking is associated with BV but may be related to the downregulation of the immune response. Racial background has also been associated with BV. Hispanic women are 50% more likely to have BV, and African American women are twice as likely.18 Although the reasons for these differences are not clear, we do know that African American women practice douching twice as often as white women and that African American women are less likely to have lactobacilli in the vagina.

• Thin, dark or dull gray, homogeneous, malodorous discharge that adheres to the vaginal walls

• Positive KOH (whiff/amine) test result

• Presence of clue cells on wet mount microscopic examination

The pH is elevated to 5 to 5.5 in most cases, and there appears to be a correlation between elevated pH and the presence of odor.19

When a patient has four or more BV episodes in a year, her underlying problem is most likely an inability to re-establish a normal vaginal ecosystem with the dominant lactobacilli. There is no definition of recurrent BV, but most clinicians would probably agree that more than four episodes in a year would define the disorder. About 30% of women experience a recurrence of symptomatic BV within 1 to 3 months, and about 70% have a recurrence within 9 months.20 It is not always clear whether the recurrence represents a relapse or a reinfection. Another possibility is that a woman may be asymptomatic at times but, because of the abnormal vaginal ecosystem, she has a chronic underlying condition, so that she is sometimes symptomatic and at other times is not. Women who are asymptomatic yet have no lactobacilli are four times more likely to experience BV. Unfortunately we do not have a proved treatment for asymptomatic women.

There are potential significant consequences of altered vaginal flora in addition to susceptibility to BV. Women with BV and without sufficient lactobacilli are more susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and gonorrhea.21,22 PID is also associated with BV. There is also now good evidence that the organisms in pregnant women with BV can ascend the genital tract and cause preterm delivery, and such women are more likely to have postpartum endometritis. Women with BV are also at increased risk for infection after gynecologic surgery.

Therapeutic Considerations

Therapeutic Considerations

Dietary Considerations

The internal milieu of the vagina is a reflection of the condition of the entire body. Vaginal secretions are continuously released that affect and are affected by the microbial flora. These secretions contain water, nutrients, electrolytes, and proteins, such as secretory immunoglobulin (Ig) A. The quantity and character of these components are altered by hormonal and dietary factors. A general healthful diet is recommended in all cases to ensure the availability of all nutrients in sufficient quantity to optimize the body’s ability to respond to changing conditions. A well-balanced diet low in fats, sugars, and refined foods is particularly important in vaginitis due to infectious organisms, particularly Candida. Patients with depressed immunity are susceptible to higher rates of infection, particularly those due to Candida, Trichomonas, and herpes (see Chapter 56 for further discussion of the effects of diet on immune function).

No other food can be considered as specifically medicinal as Lactobacillus yogurt. A 1992 study investigated the effects of the daily ingestion of yogurt containing L. acidophilus on 33 women with five or more episodes per year of candidal vaginitis. Thirteen women completed the study. The women were randomized into two groups, with the first group receiving 8 oz of L. acidophilus yogurt daily for 6 months and then no yogurt for 6 months. The other group consumed the yogurt-free diet for the first 6 months and then the diet including yogurt for the second 6 months. There was a threefold reduction in infections and in candidal colonization during the yogurt diet compared with the non-yogurt diet.23

There are also studies that do not support a role for yogurt in the prevention of recurrent candidal vaginitis.24

Nutritional Supplements

Vitamin A and Beta-Carotene

Both vitamin and beta-carotene are necessary for the normal growth and integrity of epithelial tissues, such as the vaginal mucosa. Vitamin A is essential for adequate immune response and resistance to infection. Secretory IgA, a major factor in resistance to infection, is lower in vitamin A–deficient subjects.25 Beta-carotene is a source of nontoxic vitamin A precursors. In addition, it has been shown to enhance T-cell numbers and to favorably alter their ratios.26 Excessive vitamin A can be toxic and teratogenic. This is of particular concern in women of reproductive age. Total vitamin A intake should be limited to 5000 IU/day. If larger doses of vitamin A are used, patients should be cautioned to be particularly careful about contraception. Mixed carotenoids rather than synthetic beta-carotene should be used.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree