Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the use of continuous interscalene brachial plexus block with bupivacaine to treat complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type 1 of the shoulder in adult patients who were refractory to standard therapies.

Patients and methods

We performed a prospective, cross-sectional study of 59 cases of treatment-refractory CRPS type 1 of the shoulder. The patients were treated with one week of continuous interscalene brachial plexus block with bupivacaine and concomitant rehabilitation in a specialist centre. After withdrawal of the catheter, rehabilitation was continued for a further 3 weeks.

The outcomes at 1, 6 and 12 months were evaluated in terms of the Constant score, the verbal numeric rating scale (VNRS) for pain, joint range of motion and medication use. Patients were later interviewed by telephone and asked to state their professional situation, the current VNRS score for pain and the status of their CRPS.

Results

In the first month of treatment, the mean VNRS pain score fell from 7.4 to 3.6, the Constant score rose from 21.7 to 56.6% and the joint range of motion increased from 5.4 to 29.9° for external rotation (ER) position 1 and from 38.6 to 74.2° for abduction. These improvements persisted over time, despite a very slight reduction at 6 months. 86% of the interviewed patients reported that the treatment protocol had improved or greatly improvement their condition. 46% of the respondees had been able to return to work.

Conclusion

Treatment with a combination of a 1-week continuous interscalene brachial plexus block and rehabilitation may be a good option for patients with CRPS type 1 of the shoulder and who are refractory to standard therapies.

Résumé

Objectifs

Évaluer les résultats d’une prise en charge par bloc interscalénique du syndrome douloureux régional complexe (SDRC) de type 1 de l’épaule chez l’adulte résistant aux thérapeutiques usuelles.

Patients et méthode

Étude prospective multidisciplinaire de 59 cas de SDRC de type 1 de l’épaule en échec thérapeutique, traités par bloc interscalénique continu à la marcaïne d’une semaine associée à une rééducation en centre. Poursuite de la rééducation pendant trois semaines à l’ablation du cathéter. Évaluation des résultats à un, six et 12 mois à l’aide du score de Constant et d’une échelle numérique verbale de la douleur (ENV). Suivi de l’évolution des amplitudes articulaires et de la prise médicamenteuse. Les patients ont ensuite été contactés par téléphone pour évaluer leur situation professionnelle, l’ENV et leur appréciation quant à l’évolution du SDRC.

Résultats

Dès le premier mois, diminution de l’ENV de 7,4 à 3,6. Amélioration du score de Constant de 21,7 à 56,5 %, des amplitudes articulaires qui passent de 5,4 à 29,9° pour la rotation externe (RE) position 1 et de 38,6 à 74,2° pour l’abduction ( p < 0,001). Ces résultats se maintiennent dans le temps malgré une discrète régression à six mois. Quatre-vingt-six pour cent des patients contactés par téléphone se disent améliorés ou très améliorés par la prise en charge. Quarante-six pour cent ont pu reprendre leur activité professionnelle.

Conclusion

Le bloc interscalénique continu couplé à la rééducation peut-être une alternative thérapeutique pour les patients adultes présentant un SDRC de type 1 de l’épaule rebelle aux traitements usuels.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

At its 1993 meeting in Orlando, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defined the characteristics of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) types 1 and 2 . The criteria for CRPS type 1 are an initiating noxious event and continuing pain, allodynia or hyperalgesia for which the pain is disproportionate to the inciting event (associated or not with dystrophic phenomena). This definition assimilates adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder “frozen shoulder” to CRPS type 1 .

Management of this shoulder syndrome remains problematic and treatment outcomes are often inconsistent and only partially satisfactory . The natural history of CRPS is usually considered in three stages . In the acute stage, neuropathic-type pain and vasomotor dysfunction (with oedema and sweating disorders) predominate. In the dystrophic stage (after 3 to 6 months of disease progression), motor and trophic phenomena intensify, in parallel with an increase in pain levels. Lastly, in the atrophic stage, pain levels decrease but trophic and motor disorders persist. In fact, the boundaries between these three stages are not usually so clear and it is now accepted that the presence and intensity of the different symptoms can vary . Stage II CRPS of the shoulder usually presents as neuropathic-type pain and greater shoulder stiffness during external rotation and abduction. This stage often provides the physician with a dilemma: lack of mobilization accelerates the shoulder stiffness but mobilization during rehabilitation is often prevented by the induction or accentuation of pain.

We have developed a protocol that aims at both alleviating pain and increasing joint range of motion for patients with CRPS stage II of the shoulder and for whom previous treatments have not provided sufficient relief.

This was a multidisciplinary patient management process involving physicians from the Lorient-Quimperlé Pain Clinic, orthopaedic surgeons and rehabilitation physicians.

The patient was fitted with an interscalene catheter for one week, in order to implement a continuous brachial plexus block for at least partial pain control. Rehabilitation sessions were initiated concomitantly (with a view to gaining joint range of motion) and continued for 2 to 3 weeks after catheter removal.

From 2003 to 2008, 59 patients were prospectively evaluated 1, 6 and 12 months after the block procedure. All patients were interviewed by telephone at the end of 2008.

One month after treatment, we noted significant improvements in both pain and the joint range of motion. These improvements were still present after 6 months.

1.2

Patient and methods

1.2.1

Study inclusion criteria

The study inclusion criteria were the presence of pain with a neuropathic component (according to the DN4 questionnaire) and the progressive appearance of scapulohumeral stiffness, which was defined as at least a 50% loss in joint range of motion for passive external rotation (position 1) and abduction, compared with the contralateral (and supposedly healthy) joint. All patients were aged 18 or over and had been consulting with a multidisciplinary care team in the pain clinic. All were refractory to standard treatment approaches, which variously combined World Health Organization (WHO) step 2 or 3 analgesics, gabapentin or pregabalin for the neuropathic pain component, arthroscopy-guided intra-articular infiltration of a cortisone derivative and kinesitherapy sessions (including pain relief physiotherapy and sub-pain-threshold, active-passive mobilization of the scapulohumeral joint). Pain must have been continuously present for at least 3 months and no surgery was permitted until at least 6 months after the onset of pain.

The patients had to obtain the agreement of three specialist physicians (a pain management specialist, an orthopaedic surgeon and a rehabilitation physician) seen individually, with a two-week “cooling-off” period between consultations. During each interview, the physician explained the technique to be used and the potential complications. Consent was noted in the patient’s medical records but he/she remained free to withdrawn from the study at any time. Pregnant women were excluded, as were:

- •

patients with an unsuitable psychological profile (following systematic psychological evaluation by the pain clinic’s psychologist);

- •

those who gained relief from treatments initiated during a pain consultation or during rehabilitation and;

- •

those who were suffering from a stiff but non-painful shoulder or from CRPS type 2.

Lastly, in view of the possible neurotoxic effects of bupivacaine, we excluded patients with known neurological damage to the shoulder.

1.2.2

The nerve block protocol

The nerve block protocol was developed by the Lorient-Quimperlé Pain Clinic. It involved the electrostimulation-guided, pre-sternocleidomastoid interscalene insertion of a catheter into the brachial plexus. The catheter was affixed firmly (to ensure that it remained in place for a week) and connected to a syringe pump delivering a 0.0625% bupivacaine solution at a rate of 5 mL/hour (with a peak rate of 18 mL/hour, if required). If this bupivacaine concentration was not sufficiently effective, a 0.125% solution could be used instead. The aim was to use the low-dose local anaesthetic to block the C fibres, which carry the pain signals and sympathetic stimuli. The lowest effective dose was used, in order to obtain pain relief in the absence of motor block and, if possible, sensory block. The device was left in place for a week. The basal flow rate was progressively reduced over this period. However, the flow rate was occasionally increased before rehabilitation (in order to make the latter less painful) and then reset to the baseline value once the session had been completed.

1.2.3

The rehabilitation protocol

The rehabilitation protocol was developed at the Kerpape centre. It comprised four phases.

1.2.3.1

Phase one

Phase one started with placement of the catheter. Next, with the patient lying in the supine position in a recovery room, the anaesthetist injected a bolus of bupivacaine and moved the shoulder joint twice (passive antepulsion and external rotation), in order to free any adherences.

1.2.3.2

Phase two

Phase two took place in the rehabilitation centre. The patient was treated by the same physiotherapist throughout his/her stay. In order to take advantage of the effect of the low-dose bupivacaine, the treatment was continued throughout the week. The goal was to recover joint range of motion for all types of movement. However, the rehabilitation had to remain below the pain threshold and not disturb the catheter’s positioning. The patient underwent two one-hour rehabilitation sessions per day, with gentle, progressive manipulation for all types of shoulder movement. We focused on a combination of frontal elevation, abduction and external rotation for smoothing out the inferior capsular recess. At this point in the rehabilitation programme, no rhythmic, passive movements or active work were employed. Additional muscle relaxation techniques, heat therapy and cold therapy were used sparingly (10 min per session, at most). The two hours of daily rehabilitation were mostly devoted to postural work for improving shoulder joint range of motion. Any analgesics taken by the patient for the CRPS were withdrawn during the rehabilitation period.

1.2.3.3

Phase three

Phase three began with removal of the catheter on day 8. The subsequent treatment consisted of 2 daily, 1 h sessions and was always based on sub-pain-threshold rehabilitation. Each session comprised 50 min of passive mobilization, active assisted mobilization and active mobilization and then 10 min of physiotherapy. The range of motion work continued, together with exercises for recentering the humeral head, pain relief massage therapy, electrotherapy (endorphin release with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation), thermotherapy and contracture release. We also initiated active work on the muscles involved in stabilizing the scapula and recentering the humeral head. The exercises were initially static but progressed to eccentric and then concentric dynamic work. At this point, we tacked control of pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi co-contraction by progressing the arm elevation from 0 to 60° and then 120 and 160° and, lastly, focusing on the 60 to 120° range (typically the most painful, due to potential conflict).

1.2.3.4

Phase four

Phase four completed the course of treatment in the rehabilitation centre, with renewed use of the arm in motor activities, muscle strengthening and proprioceptive retraining. This was complemented by 1 h of balneotherapy in the presence of a physiotherapist.

Hence, the various treatment phases constituted a progression from solely scapulohumeral work towards more general arm exercises at the end of the rehabilitation programme.

1.2.4

Evaluations

Patients were assessed before the block and then 1, 6 and 12 months later by using the Constant score according to the author’s recommendations and a verbal numeric rating scale (VNRS) ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable). We measured passive abduction in the scapulohumeral plane and passive external rotation (in position 1) three times. The patient’s medication use and professional situation were noted. All the follow-up evaluations were performed by physicians who had not been involved in treating the patient. However, each patient was examined by the same physician each time. One of the investigators (a rehabilitation physician) performed the telephone survey in late 2008 and asked the patients to state their current professional situation, pain level (on the VNRS) and opinion concerning the progression of the CRPS (i.e. whether they felt worse, the same, better or much better after the treatment). They were also asked whether they would wish to undergo the same course of treatment again, if indicated.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

The study population

A total of 59 patients (19 men and 40 women) were included in the protocol between 2003 and 2008. The mean age was 50 years (range: 31 to 72). The mean time since onset of the CRPS was 14 months (range: 3 to 60 months) and affected the right shoulder in 34 cases and the left shoulder in 25 cases. Fifty-four patients were seen at 6 months and 52 were contacted by telephone after an average follow-up period of 3 years. Only 23 patients could be evaluated in a consultation 12 months after the treatment.

1.3.2

Pain levels

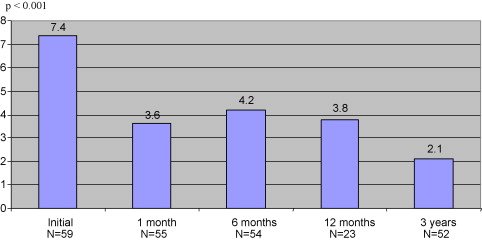

Over the first month, the initial pain VNRS score fell from 7.4 to 3.6 ( P < 0.001). There was a very slight rebound at 6 months (with a VNRS score of 4.2; P < 0.001) but the results were stable over time (with a pain VNRS score of 3.8 at 12 months and 2.1 at the time of the phone survey; P < 0.001) ( Fig. 1 ).

1.3.3

The Constant score

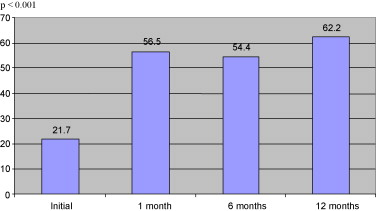

The Constant score rose from 21.7 to 56.5% at 1 month ( P < 0.001). This improvement persisted over time (54.4% at 6 months and 62.2% at 12 months; P < 0.001) ( Fig. 2 ).

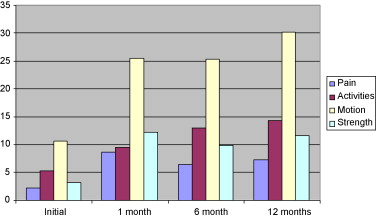

The improvement concerned all four items of the Constant score, which were evaluated individually ( Fig. 3 ). Strength gains were modest but remained statistically significant ( P < 0.001).

1.3.4

Passive mobility

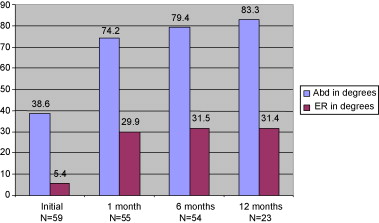

The shoulder joint’s external rotation range rose from 5.4° before treatment to 29.9° at 1 month, 31.5° at 6 months and 31.4° at 12 months. The joint’s abduction range increased from 38.6° at baseline to 74.2° at 1 month, 79.4° at 6 months and 83.3 at 12 months ( P < 0.001 at all time points) ( Fig. 4 ).

1.3.5

Medication use

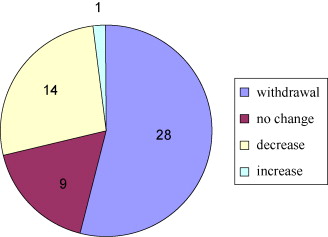

At the l-month evaluation, 50 of the 59 patients were only taking step 1 analgesics. The remaining nine were on step 2 analgesics. Twenty-eight patients had been able to abandon analgesic treatment after three years and 14 others had been able to reduce their dose or move to a lower WHO step ( Fig. 5 ).

1.3.6

The telephone survey

Fifty-two of the 56 patients were contacted; of these, 86% said that they felt better or much better as a result of the treatment. Almost 70% were ready to renew treatment with the nerve block catheter, if required. In terms of professional activity, 24 patients had been able to return to work and seven had retired in the meantime. Thirteen of the 51 patients remained on long-term sick leave ( Fig. 6 ).

1.4

Complications

During the treatment period, we noted 13 complications:

- •

five catheter occlusions;

- •

two cases of partial paresis;

- •

one case of pneumothorax;

- •

one catheter displacement;

- •

one case of deep vein thrombosis of the leg;

- •

ne case of haematoma at the puncture point;

- •

one episode of major anxiety and;

- •

one case of a catheter-related increase in pain.

These complications all occurred during the first month of treatment and did not have long-term, harmful consequences for the patients.

The occlusions prompted catheter repositioning and did not require the treatment to be interrupted. There were no negative effects on the outcome.

The two cases of partial paresis (in the C5 and C6 segments) were related to the catheter’s positioning and bupivacaine’s neurotoxic effects. Full motor recovery took just 2 months for one patient but over a year for the second.

The case of pneumothorax during catheter placement did not require drainage but did prompt the operation to be postponed.

Movement of the catheter during rehabilitation required repositioning and did not cause the treatment to be interrupted.

There was no clear causative link between our treatment protocol and the case of deep vein thrombosis of the leg.

The hematoma at the puncture point did not have any impact other than a week-long increase in pain levels.

Lastly, it should be noted that the episode of major anxiety and increased pain in one patient throughout the period of catheter use led to a disappointing treatment outcome.

1.5

Discussion

It is important to note that the patients included in this study presented CRPS type 1 of the shoulder with intense pain (a baseline VNRS score of 7.4) and significant stiffness (external rotation in position 1 of 5.4° and abduction of 38.6°), despite multidisciplinary follow-up in a pain clinic and the initiation of standard treatments for this pathology (as specified in the inclusion criteria) . Our study had the advantage of only including patients who were refractory to other therapies. Despite these “difficult cases”, our method produced significant decreases in pain and increases in joint range of motion within the first month. The results were slightly less good at 6 months but remained stable thereafter. This type of change over time has also been reported in the literature . Even though improvement is usually significant and rapid, it is only partial in most cases – regardless of the type of therapy . Manipulation under anaesthesia , arthroscopic release , hydraulic capsule distension and non-surgical treatments all fail to resolve residual pain or loss of mobility. Massoud et al. compared manipulation under anaesthesia, arthroscopic release and open arthroscopy and found residual pain in half of the cases . In a series of 45 patients treated with arthroscopy, Gerber et al. observed that most experienced some residual pain and loss of mobility and that a return to work was often delayed or prevented . Doddendorff et al. found that after more than 5 years, pain and stiffness persisted in 53% of his 75 patients treated with manipulation under general anaesthesia . The improvement observed in the present study had professional repercussions because of the 52 patients on long-term sick leave before the treatment, only 13 were professionally inactive 3 years afterwards. This outcome appears to be better than in other studies . Almost all the patients had been able to reduce their analgesic use after removal of the catheter and over half had stopped using analgesics after 3 years. Unfortunately, a lack of full data on the medication intake at 6 and 12 months prevented us from performing a valid analysis for these time points.

It is noteworthy that neither the initial professional situation (workplace accident, work-related disease, etc.) nor the occurrence of complications during the study period had an effect on the treatment outcome. The only statistically significant, negative predictive factor was the absence of a decrease in pain during the first phase of treatment (i.e. when the nerve block catheter was in place).

To the best of our knowledge, only four groups have reported on studies in which bupivacaine was used to treat painful, stiff shoulders . The nerve blocks were suprascapular in two studies, interscalene in the third study and intra-articular in the fourth study. However, these results are difficult to interpret because the series were small and very heterogeneous and did not difference between and evaluate CRPS types 1 and 2 or between the various disease phases. Continuous perfusion was only used in one case.

Bupivacaine is known for its preferential effect on the smallest fibres, including C fibres and sensory fibres. At the concentrations used in our treatment protocol, bupivacaine mainly targets the C fibres. It is interesting to note that in the great majority of cases, interscalene block enables pain control and, above all, that the pain level hardly increases when the block is removed.

This could be due to continuous, prolonged blockade of the C fibres by bupivacaine.

The lack of a control group means that our results must be interpreted with a degree of caution. Although the significant progress made by treatment-refractory patients in the first month post-block emphasizes the efficacy of our treatment programme, the assessments are at 1 and 3 years are more delicate, given the natural history of CRPS type 1. Moreover, we were only able to assess 23 patients at 1 year post-block. However, during the telephone interview at 3 years (with 52 of the 59 patients), it is interesting to note that the great majority said that their condition had been improved or very much improved by our treatment programme. Despite the burdensome nature of the protocol, 70% said that they would undergo the same treatment again, if needed. Patients who failed to respond adequately to the continuous interscalene brachial plexus block were provided with follow-up treatment in the Lorient-Quimperlé Pain Clinic.

1.6

Conclusion

Although the long-term outcomes in the present series do not appear to differ fundamentally from those reported in the literature, our treatment protocol significantly decreased pain and increased shoulder joint range of motion (from the first month of treatment onwards) in CRPS stage II patients who were refractory to conventional therapies. Despite a slight deterioration at 6 months, these initial gains were stable over time.

Conflict of interest

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree