Abstract

Introduction

The Melbourne unilateral upper limb assessment evaluates upper limb function in children with neurologic impairment aged from 5 to 15 years old. Its validity and reliability have been well demonstrated for the English version, which supports this tool as a reference tool.

Objectives

To present the French version of the Melbourne, its validity and reliability in order to offer French-speaking clinicians a relevant tool.

Patients and methods

The criterion validity was studied in a group of 46 children (mean age 10.6 years, gross motor function classification system in cerebral palsy [GMFCS] 1 to 4) in comparison with Box and Block test; the intra-rater and inter-rater reliability was studied in a group of 11 hemiplegic children (mean age 9.8 years, GMFCS 1 or 2).

Results

The French version of the Melbourne test has a good criterion validity, with a good correlation between the score of Melbourne and the score of Box and Block test; the intra-rater reliability is very high or excellent, the inter-rater reliability is good on the whole, from moderate to excellent depending on the items.

Conclusion

The Melbourne test is a tool which has good psychometric properties. The French version is usable and reliable.

Résumé

Introduction

Le test de Melbourne est une échelle d’évaluation de la fonction du membre supérieur chez les enfants de cinq à 15 ans présentant une pathologie neurologique. Sa validité et sa fiabilité ont été largement démontrées en langue anglaise et en font un outil de référence.

Objectifs

Présenter la validité et la fiabilité de la version française du test de Melbourne pour offrir aux cliniciens francophones un outil pertinent.

Matériel et méthode

La validité critériée a été étudiée sur un groupe de 46 enfants (âge moyen 10,6 ans, gross motor function classification system in cerebral palsy [GMFCS] allant de 1 à 4) en comparaison au Box and Block test ; la fiabilité intra- et interexaminateur a été étudiée sur un groupe de 11 enfants hémiplégiques (âge moyen 9,8 ans, GMFCS 1 ou 2).

Résultats

La version française du test de Melbourne présente une bonne validité critériée, avec une bonne corrélation entre le score de Melbourne et le score de Box and Block test ; la fiabilité intra-examinateur est très bonne ou excellente, la fiabilité interexaminateur est globalement bonne, variant de modérée à excellente selon les items.

Conclusion

Le test de Melbourne est un outil de bonne construction psychométrique, fiable et utilisable dans sa version française.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The variety of tasks involving upper limb function is probably partly responsible for the difficulty to assess this function in a reliable manner. It is indeed hard to suggest one or two stereotyped tasks representative enough for numerous functions of the upper limb. Pointing, pressing, pushing, pulling, grasping, holding, releasing, manipulating… are all functions that need complicated movements in the upper limb.

In children with cerebral palsy, upper limbs movements generally present pathologic motor patterns, showing muscle tone troubles (dystonia, spasticity) often associated with muscle deficiency, whose natural evolution we don’t really know.

Moreover, the upper limb has often been neglected compared to the lower limb, as treatment priority often tends to get children walk.

But the use of new therapeutic methods, as for example botulinum toxin, becomes now more and more usual and requires a reliable assessment of upper limb function, in order to measure its evolution and the treatment’s effects.

To be reliable, evaluation should be adapted to the assessed population and use tools with good psychometric properties . Until now, no French quantified tool was available to assess upper limb function in children with cerebral palsy. Validated assessment tools in French language are very few, often fragmented and not really adapted to upper limb function in cerebral palsy . We can indeed not reduce functional abilities to a dexterity score obtained with a standardized test in normal children. Neither can we settle for subjective observations made by the therapist, even if his/her clinical judgement is very good, to measure one treatment’s effects and efficacy. It seems therefore essential to get some valid assessment tools, reliable and responsive to change, especially after a therapeutic intervention. Some English scales do already exist and give evidence, but we need to translate and validate them in French language to use them. The Melbourne unilateral upper limb assessment was developed since 1986 until 1994 by Melinda Randall’s team at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne . This tool was created to measure upper limb function in children with neurological impairment aged from 5 to 15 years, and designed to evaluate motor function as well in spastic forms as in dystonia, hypotonia, ataxia or athetosia. Its validity and reliability have been wildly demonstrated and the test is commonly used in English-speaking studies.

The aim of this paper is to present the French version of the test de Melbourne , its validity and its reliability in children with congenital hemiplegia.

1.2

Material and methods

1.2.1

The Melbourne unilateral upper limb assessment – test de Melbourne

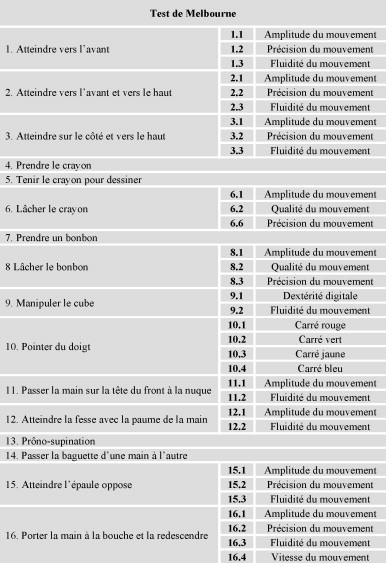

The Melbourne test is an unilateral assessment of the upper limb function, that is to say that each upper limb is assessed separately. The child’s performance is filmed according to a video protocol, and the video is scored afterwards, following the specific instructions of the manual. For each of the 16 items and each subskill, scoring criteria have been defined to take in account all movement’s aspects. Each subskill is scored on a three, four or five point scale.

The 16 items of the Melbourne test are representative for most important aspects of upper limb function, and call upon decisive functions in children with cerebral palsy (as for example supinate forearm, or reaching the back of the head…).

Items are not strictly analytical but are all connected with functional tasks (as putting something to mouth…), while pointing motor abilities. Language, cognition and perception are solicited as few as possible to make the test passation easier in children with moderate to severe neurological impairment.

Items are accurately scored, subskill after subskill, according to the scoring criteria defined by the manual, to let the smallest importance to the tester’s subjectivity. The test kit includes the manual and all material required for the evaluation. Fig. 1 presents the 16 items of the Melbourne test.

The total score of the Melbourne is obtained by adding scores of the evaluated items and is converted then in a percentage score. The higher the percentage score obtained by the child, the better the quality of movement in the evaluated upper limb. A normal child obtains 100%.

The test lasts about 30 minutes, but it depends on child capacities and cooperation. For the administration, one person gives instructions to the child and presents the material while another person is in charge of the video. Thirty minutes more are then necessary to see and score the video.

The reliability studies conducted between 1995 and 1997 on the English version showed that the Melbourne test is a valid tool to evaluate upper limb function in children with cerebral palsy, that it objectively evaluates this function by giving a numeric score to the quality of movement.

In the English version, intra- and inter-rater reliability of the items’ scores was moderate to high; intra- and inter-rater reliability of the total scores was high; test–retest reliability of the items’ scores for the same rater was moderate to high; test–retest reliability of the total scores for the same rater was high .

The Centre médico-chirurgical de réadaptation des massues takes the entire responsibility for the translation of the Melbourne test into French, which was made with translation/back translation with Royal Children’s Hospital’s approval, in preparation for clinical and research use in French-speaking countries.

The translation of this toll was in line with the development of our assessment protocols for botulinum toxin treatment in children’s upper limb. “The Melbourne assessment of unilateral upper limb function”, widely quoted in English-speaking literature, seemed to suit French therapists’ needs and we began to translate items and administration procedure from 2006. The French version was then studied for its psychometric validity.

1.2.2

Population and methods

Validity studies for the French version were conducted in different groups.

For the criterion validity, the study was about a group of 46 children with neurological impairment (5% quadriplegia, 9% triplegia, 76% hemiplegia and 10% monoplegia), mean age 10.4 (5 to 16 years old, median 9.5 years); 26 boys and 20 girls. All children who benefited from both Melbourne and Box and Block tests during the years 2006 and 2007 were retrospectively included in the study. According to the gross motor function classification system in cerebral palsy (GMFCS) , the children included in the studied group were as a majority GMFCS 1 or GMFCS 2, with yet few children GMFCS 3 or GMFCS 4. Melbourne scores varied between 23.5 and 95% (median 72%). The Melbourne score was compared to the Box and Block test’s score obtained by the same upper limb; this global dexterity test is normed in children between 6 and 19 years old , is easy to administer, doesn’t prone to different viewpoints and is routinely used. The child must in 1 minute put as many cubes as possible from one side to the other side of a compartmentalized box.

For the internal consistency, the intra-rater reliability, the inter-rater reliability and the total score reliability, the study was about a group of 11 children with hemiplegia, GMFCS 1 or 2, mean age 9.8 years (5.5–15.5 years old); five boys and six girls; eight right hemiplegia and three left hemiplegia. Functional levels of the 11 children were well representative, as the Melbourne scores obtained varied from 38 to 94%.

Two experienced occupational therapists looked at the videos. For the intra-rater reliability, the same video was analyzed by the same rater at 3 months interval. For the inter-rater reliability, the same video was analyzed by the two raters separately, without any exchange.

Data were first collected on papers and then collected on computer with double check. Statistical analysis was made with Excel and SPSS 16.0, using Cronbach’s alpha, Pearson correlation coefficient, Kappa’s weighted coefficient, Bland-Altman’s agreement .

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Internal consistency

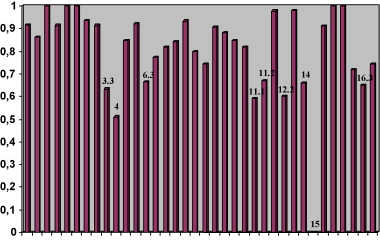

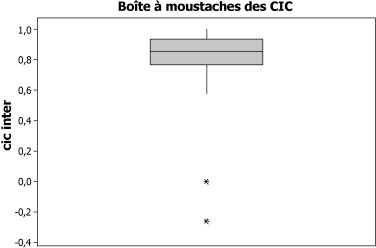

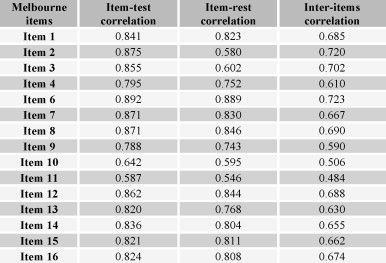

Studying internal consistency for a test intends one side to prove that there is a real homogeneity between test’s items, that is to say that all measured parameters are linked to each other and that the results found for the different parameters are not contradictory; on another side, test’s items should not exactly measure the same parameters to avoid redundancy. Melbourne test claims measuring upper limb function. If all items effectively measure upper limb function, we can suppose that there is a correlation between each item and all other items of the test, and that there is a correlation between each item and the total score. The importance of the link between items, that is to say internal consistency or homogeneity, was studied with Cronbach’s alpha. Fig. 2 shows that inter-items correlations are moderate (mean 0.65) and that item–rest correlations are high, which attests the good internal consistency of the French version of the Melbourne test. Item 5 (drawing grasp) was not taken in account in the study because of all missing values. This item is indeed not very relevant when assessing affected upper limb in children with hemiplegia, who always use the dominant hand to write. In children with quadriplegia, upper limb is most of the time too much affected to let the child use a pencil to write.

1.3.2

Criterion validity

Criterion validity is established by assessing the same phenomenon by both the Melbourne test and another criteria as reference, and by measuring the intensity of the link between the two assessments.

This aspect of validity is particularly difficult to evaluate… actually is the Melbourne test a functional scale which allows to quantify the quality of movement for different kinds of movements in the upper limbs. As far we know, we could not have assessed our patients with another comparable tool and found afterwards a good statistical link with the results obtained with the Melbourne test. Valid tools which are routinely used often give only a dexterity score, more representative for “productivity” than for “movement quality”… We yet have stated the hypothesis that movement quality influences productivity… and we chose to compare the results obtained with the Melbourne test to the results obtained with the Box and Block test. The score obtained with the Box and Block test matches the number of moved cubes. The Box and Block test is thus mainly based on abilities for global grasping, holding, carrying and releasing. It does not need precise handling, as for example the Purdur Pegboard test , which seems to be too demanding for children suitable to be assessed with the Melbourne test.

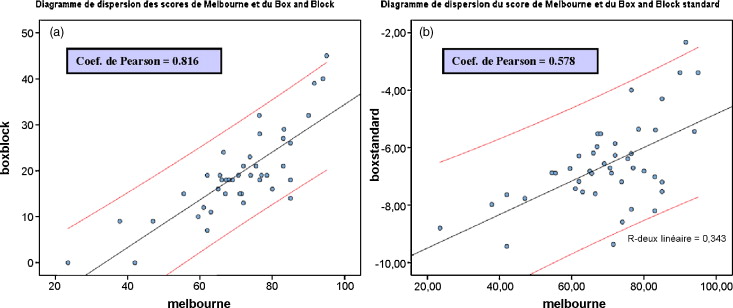

The score obtained with the Box and Block test can be given as a raw score, or expressed with standard deviations to a mean for a specific age group. Fig. 3 presents the scatter diagrams comparing the Melbourne scores to the raw Box and Block scores first, and to the standard Box and Block scores secondly, with the Pearson’s correlation coefficients comparing these quantitative variables.

These coefficients show a good correlation between the Melbourne score and the raw Box and Block score ( p = 0.816) and a moderate correlation between the Melbourne score and the standard Box and Block score ( p = 0.578).

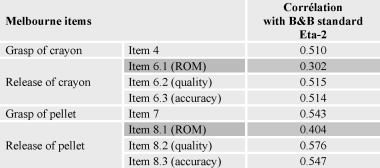

We then isolated Melbourne test’s items representing “grasping–releasing” function (item 4, item 6, item 7, item 8) and looked for correlations between these items’ scores and standard Box and Block score. Results are presented in the table ( Fig. 4 ) and show a moderate correlation between grasping items and Box and Block score, a moderate correlation between items specifying the precision of release and Box and Block score, and a poor correlation between the release’s range of movement and the Box and Block test.

1.3.3

Intra-rater reliability

Kappa’s coefficient was used to measure the agreement between two evaluations of the same video by the same rater. This coefficient is routinely used to measure agreement between matched qualitative judgments. Weighted Kappa’s coefficients were used here to take into consideration the severity of judgment error; a one point-difference was considered as less severe than a two-, three- or four-points difference.

The agreement is said excellent if Kappa ≥ 0.81, good if 0.81 > Kappa ≥ 0.61, moderate if 0.61 > Kappa ≥ 0.41, poor if 0.41 > Kappa ≥ 0.21, bad if 0.21 > Kappa ≥ 0, very bad if Kappa < 0.

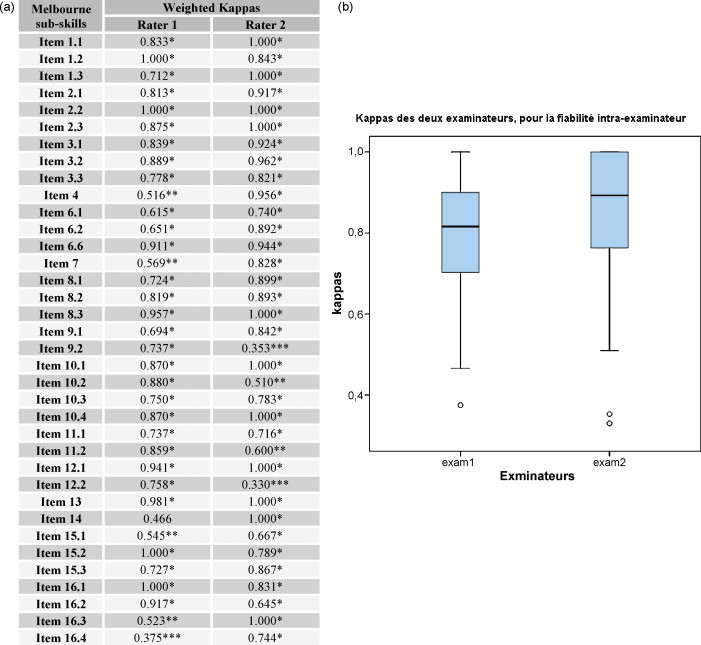

Fig. 5 a and b present weighted Kappas obtained by comparing two similar evaluations’ series made by rater 1 and two similar evaluations’ series made by rater 2, for each subskill. On the whole, Kappas show a good reliability for rater 1 and an excellent reliability for rater 2, with yet a poor reliability in few items or subskills for each rater (poor reliability for subskills 9.2: fluency in manipulation; 12.2: fluency in palm to bottom; 16.4: speed in hand to mouth and down).

1.3.4

Inter-rater reliability

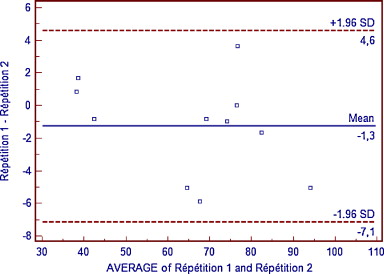

Kappa’s coefficient was used again to measure agreement between raters for each subskill. Fig. 6 sums up results and shows that inter-rater reliability is globally good, with a majority of subskills obtaining a good to excellent agreement, a moderate agreement for subskills 4 and 11.1 and a bad agreement for subskill 15.1. These results were confirmed by using the intraclass correlation coefficient, which shows a good inter-rater reliability for all items, except subskills 15.1 and 16.3 ( Fig. 7 ). The Fig. 8’s graph represents Bland-Altman agreement’s limits and shows differences between rater’s scores, with a mean line and a confidence interval to 95%.