Unusual Instability Patterns

Waitin’ to climb a hill don’t make it smaller.

While the majority of glenohumeral instability is anterior, the arthroscopist must also be adept at recognizing and treating unusual patterns of instability including posterior instability, triple labral lesions, humeral-sided capsuloligamentous disruption, and multidirectional instability. Because these patterns are less common, they can often go unrecognized or be misdiagnosed. Furthermore, their repair techniques are less familiar to surgeons than techniques for standard Bankart repair. Each pattern presents unique technical challenges that are discussed below.

POSTERIOR INSTABILITY REPAIR

Patients with posterior instability commonly present with one or both of two major complaints: posterior pain and posterior instability. These two symptoms should be clearly delineated and may assist the surgeon in making the appropriate preoperative and intraoperative treatment decisions. Furthermore, many patients may present with similar symptoms but with diverse pathologies (e.g., nonlabral tear instability, osteochondral defects, and glenoid version abnormalities). Although the vast majority of patients with posterior instability may be treated arthroscopically, certain patients may not be reliably treated arthroscopically and may require open posterior bone grafting (e.g., glenoid version abnormality).

Patients with posterior pain commonly present with a history of an acute traumatic injury (e.g., defensive lineman with posterior translational load), complaints of pain along the posterior joint line with activities (e.g., bench press, overhead press, dips), a positive relocation sign for pain (i.e., similar to a posterior SLAP lesion), pain with posterior load and shift, and a tear of the posterior labrum but with minimal signs of true instability. In contrast, many patients with true posterior instability will demonstrate pain and general soreness, but with the predominant complaint of instability, generalized ligamentous laxity, a positive sulcus sign, a positive Jerk test, and the ability to demonstrate their instability. In many cases, the instability is voluntary but positional; that is, the patient’s shoulder is dislocated/subluxed in the position of forward flexion, pronation, and internal rotation but relocates with the arm brought into abduction and extension (circumduction sign).

In this scenario, it is critical to obtain a high-quality MR arthrogram to determine if a true posterior labral tear is present. Despite having voluntary, positional posterior instability, patients with concomitant posterior labral tears may benefit from posterior labral repair and capsular shift. In contrast, in patients with voluntary, habitual, positional posterior instability, without a labral tear, the arthroscopist should reemphasize the importance of nonoperative treatment and the regaining of dynamic muscular stability and control.

MR arthrogram and radiographs should also be evaluated for the presence of a posterior bony Bankart or degenerative changes of the glenoid. Posterior bony Bankart lesions are commonly associated with an acute instability episode. However, patients with pure cartilage damage and decreased glenohumeral joint space, particularly if associated with symptoms of pain and minimal history of trauma, may present with a degenerative posterior labral tear and early osteoarthritic symptoms. Management of arthritic posterior lesions with arthroscopic repair may not provide long-term relief of symptoms. Like all labral tears, posterior labral tears may also have associated paralabral cysts, which may be decompressed appropriately through the lesion. Unlike spinoglenoid cysts, posterior or posteroinferior labral cysts do not result in compression of the suprascapular nerve with suprascapular neuropathy.

Finally, patients who have experienced a true posterior dislocation episode will commonly present with pain and symptoms of instability. In this situation, careful evaluation of the MR arthrogram will usually demonstrate the presence of a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion indicative of a true instability episode. Chronic locked posterior dislocations or posterior dislocations associated with major traumatic injury (e.g., epilepsy, electrical shocks) may have large reverse Hill-Sachs lesions that require treatment (e.g., reverse remplissage).

Posterior Labral Repair (Knotted Suture Anchor Technique)

In patients with a pure posterior labral tear with minimal complaints of instability and without the presence of a major reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, a standard posterior labral repair is indicated. In this situation, because ligamentous laxity is usually not present, large capsular plication stitches in conjunction with posterior labral repair are not indicated.

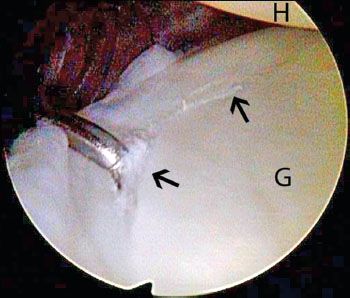

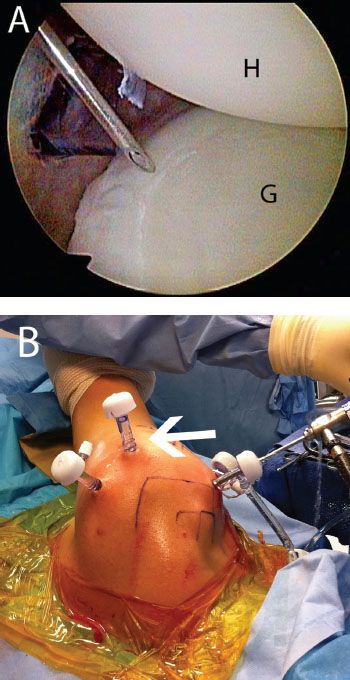

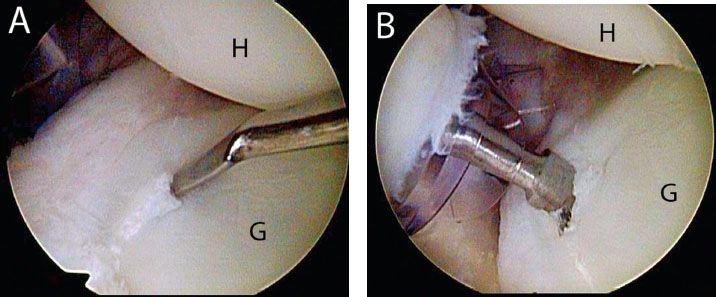

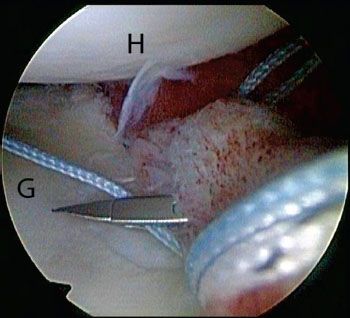

Standard three-portal access to the glenohumeral joint is initially established including anterior, anterosuperolateral, and posterior portals. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed and the glenohumeral joint is viewed through the anterosuperolateral portal to identify the posterior labral tear (Fig. 14.1). Since the standard posterior portal is tangential to the face of the glenoid, this portal does not provide an adequate angle of approach to the posterior glenoid for labral mobilization, glenoid neck preparation, and anchor insertion. A separate posterolateral portal is created approximately 4 cm inferior to the posterolateral corner of the acromion at approximately a 45° angle of approach toward the posterior inferior glenoid rim (Fig. 14.2).

Figure 14.1 Left shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal demonstrates a posterior Bankart lesion (black arrows). G, glenoid; H, humerus.

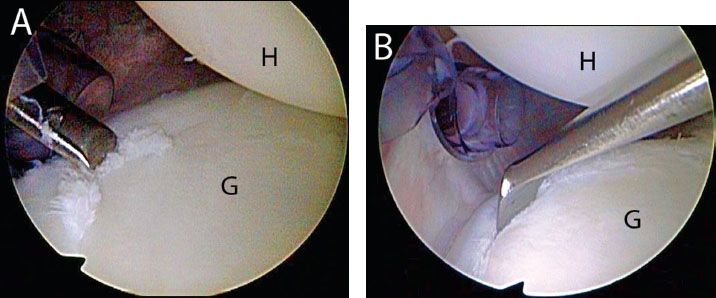

The posterior labrum is mobilized off the glenoid neck using an elevator or arthroscopic scissor. The correct angle of approach for mobilization of the posterior labrum is commonly and surprisingly through the anterior portal (Fig. 14.3). This portal is especially helpful for the initial release of the labrum off the rim of the glenoid followed

Figure 14.2 Left shoulder demonstrates placement of a posterolateral portal. A: Arthroscopic view from an anterosuperolateral portal shows the use of a spinal needle to determine an appropriate angle of approach to the posteroinferior glenoid. The cannula of the standard posterior portal is seen in the background. B: External view shows the location of the posterolateral portal (white arrow) relative to the posterior portal and the posterolateral acromion. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

Figure 14.3 Left shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal demonstrates mobilization of a posterior Bankart lesion. A: In this case, the angle of approach through the posterior portal is too acute to properly mobilize the labrum. B: A 30° elevator introduced from an anterior working portal provides a proper angle of approach to mobilize the posterior labrum. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

If the anterior portal does not provide a correct angle of approach, the posterolateral portal may provide the correct angle of approach while viewing through an anterosuperolateral portal (Fig. 14.5). The labrum is elevated off the posterior glenoid neck and the posterior neck is debrided with a shaver and curette (Fig. 14.6).

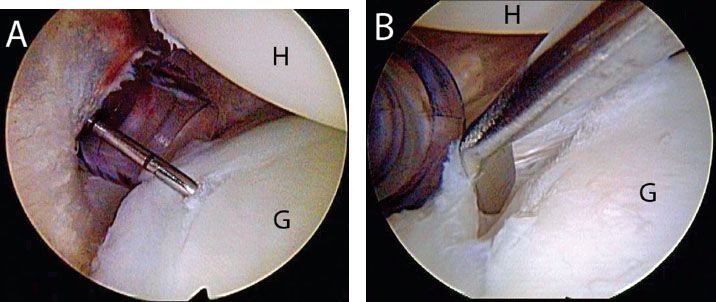

Anchors are then inserted along the posterior glenoid rim starting from inferior to superior. Anchors are inserted through the posterolateral portal just onto the articular surface of the glenoid. Usually two or three anchors are required and may be sequentially placed (Fig. 14.7). We prefer 3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak anchors double loaded with No. 2 FiberWire (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL). In patients with chondral damage leaving exposed glenoid bone, the anchors may be placed slightly further onto the glenoid face to advance the labrum over the chondral defect and provide a soft tissue interposition while repairing the labrum (see Chapter 22, “Glenohumeral Arthritis”).

Figure 14.4 Left shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal demonstrates (A) a hidden posterior Bankart lesion that is revealed with a probe. B: An elevator introduced from an anterior working portal shows that the labrum is not firmly attached to the posterior glenoid. When a posterior Bankart lesion is suspected, it is important to probe for hidden lesions that can be missed with a cursory examination. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

Figure 14.5 Left shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal demonstrates mobilization of a posterior Bankart lesion. A: In this case, the angle of approach through the anterior portal is too acute to properly mobilize the labrum. B: A 15° elevator introduced from a posterolateral working portal provides a proper angle of approach to mobilize the posterior labrum. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

Once anchors are placed, sutures are passed through the labrum. In patients with pain but with minimal complaints of instability, a standard labral repair may be performed without major capsular shift or plication. Similar to anterior labral repair, multiple options are available to pass sutures including antegrade suture passage (Scorpion; Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL), a shuttling technique (SutureLasso; Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) and retrograde suture passage (BirdBeak; Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL).

Antegrade suture passage does not require an extra step of shuttling and makes a small puncture hole through the capsule or labrum. If labral mobilization was performed through an anterior portal, this usually indicates that antegrade suture passage may be performed with a Scorpion suture passer in the anterior portal while viewing through the anterosuperolateral portal. Alternatively, if the anterosuperolateral portal was used for labral mobilization while viewing through the anterior portal, the Scorpion may be placed through the anterosuperolateral portal. Using either approach, the Scorpion can sometimes be used for suture passage in the posterior labrum (Fig. 14.8).

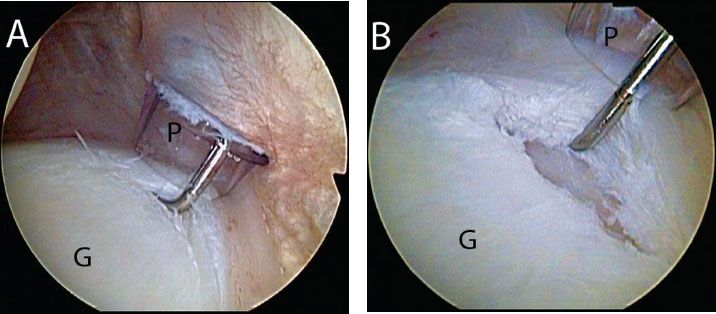

Figure 14.6 A: Right shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal demonstrates a hidden posterior labral lesion. B: Same shoulder following completed preparation for repair of the posterior Bankart lesion. A strip of bare bone has been prepared to facilitate healing of the labrum to bone. G, glenoid; P, posterior portal.

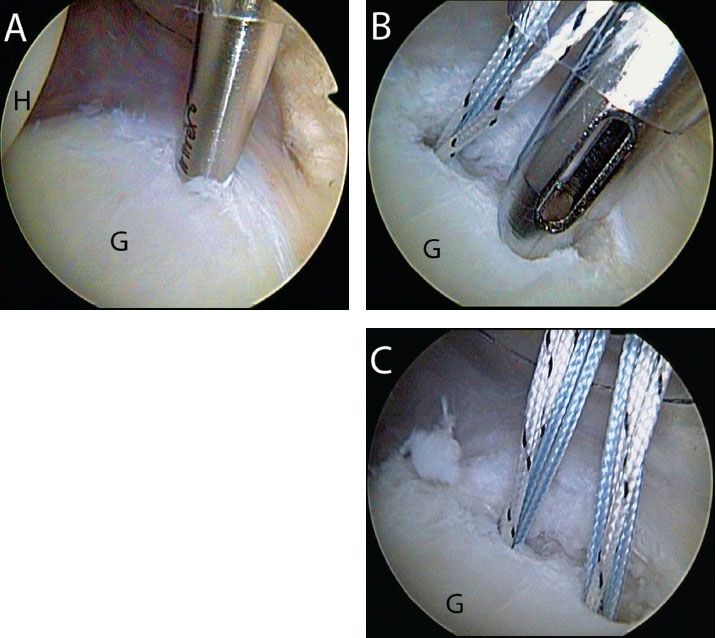

Figure 14.7 Right shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal demonstrates anchor placement for a posterior Bankart repair. A: An inferior anchor is placed slightly onto the face of the glenoid via a posterolateral portal. B: A second anchor is placed prior to passing sutures. C: Appearance after placement of both anchors. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

Figure 14.8 Right shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal. A Scorpion (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) is introduced from an anterior working portal and used to pass a suture through the posterior labrum. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

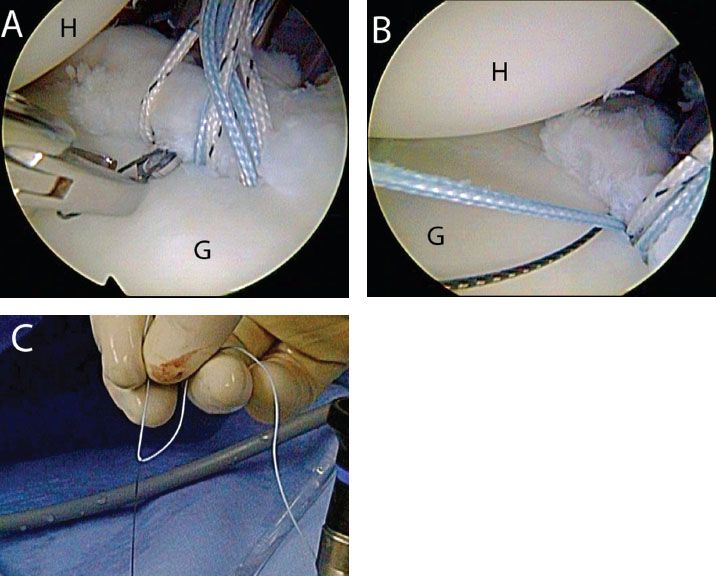

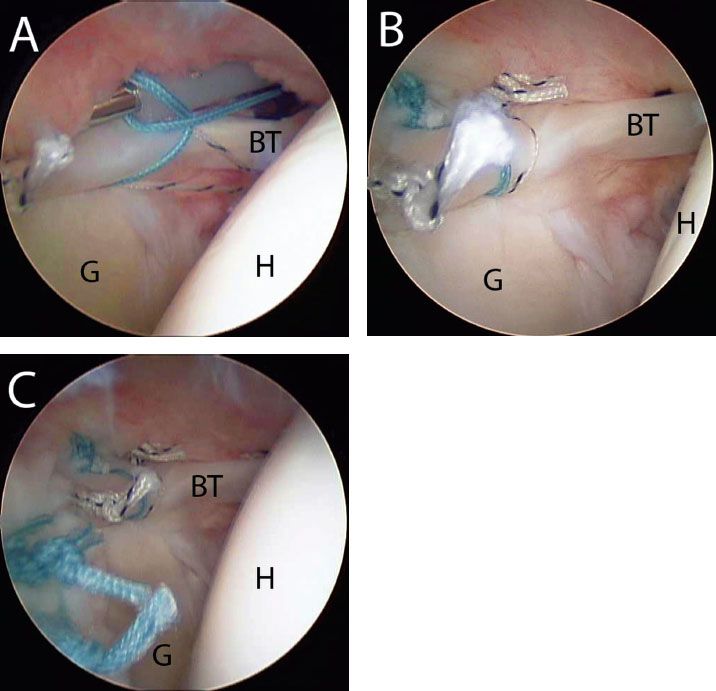

Figure 14.9 Right shoulder demonstrates suture shuttling for a posterior Bankart repair. A: A SutureLasso (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) is passed through the posterior labrum and (B) retrieved out an anterior working portal along with one of the sutures. C: Externally, the suture limb is threaded through the loop in the Nitinol wire so that it may be shuttled through the labrum. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

A shuttling technique is used when the angle of approach does not allow antegrade suture passage. In addition, the shuttling technique is useful when previous fixation (i.e., suture passage and fixation with knot tying) has bound the labrum and prevents the use of larger instruments (e.g., Scorpion). Shuttling is usually performed while viewing through an anterosuperolateral portal with instruments inserted through a posterior portal or posterolateral portal. The remaining portal is used as a suture management and suture shuttling portal.

The correct angle of approach for suture passage is usually obtained with a 25° Tight Curve SutureLasso (left curved for a right shoulder) in the posterior inferior quadrant, a Straight SutureLasso directly posterior, and an opposite25° Tight Curve SutureLasso (right curve for a right shoulder) in the posterior superior quadrant. After passing the SutureLasso, the suture and suture shuttle are retrieved through another portal and then relayed through the labrum (Fig. 14.9).

Retrograde suture passage using BirdBeak suture passers may also be used for labral repair. Retrograde suture passage is usually most valuable for suture passage directly posteriorly or for an anchor within close proximity of the utilized portal (Fig. 14.10). This is due to the limited angular change permitted by retrograde suture passing instruments. Furthermore, if significant capsular plication is indicated, the larger BirdBeak instrumentation may be contraindicated because it creates a significant hole through soft tissue, potentially damaging the more fragile capsule.

Figure 14.10 Right shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal, demonstrates use a BirdBeak (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) to pass sutures for a posterior labral repair. The BirdBeak is useful when the angle of approach to the sutures is in line with the posterior portal. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

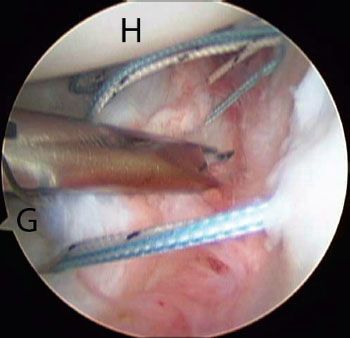

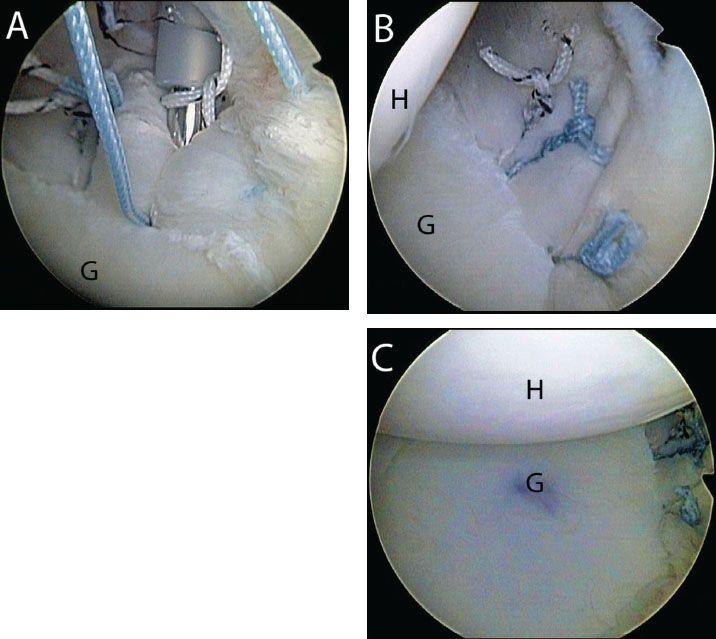

Figure 14.11 Right shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal. A: After suture passage knots are tied for a posterior Bankart repair using a Surgeon’s Sixth Finger Knot Pusher (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL). B: Close-up view of the final repair shows restoration of the posterior labral bumper. C: Profile view of the final repair demonstrates that the humeral head is centered over the glenoid. G, glenoid; H, humerus.

A “tie as you go” technique is used to sequentially pass and tie sutures from inferior to superior, securing the final repair construct (Fig. 14.11).

Combined Posterior Labral Tear and SLAP Lesion

A combined posterior labral tear and superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesion is commonly encountered in patients with posterior pain following a traumatic injury. Essentially the same repair technique may be performed as above. A standard four portal approach is again established. Both the superior labrum and posterior labrum are mobilized and the glenoid bone is prepared.

Usually the posterior labral tear is contiguous with the superior labral tear and the entire posterior half of the glenoid labrum is prepared (Fig. 14.12). In some cases, a small portion of posterior superior labrum may be intact. In this scenario, we will commonly complete the tear, making it contiguous to ensure adequate mobilization and repair.

In combined cases, the SLAP lesion anchors and sutures are passed first. Usually, this progresses with anchor insertion through the anterosuperolateral portal followed by passage through the labrum just posterior to the biceps root, followed by posterolateral anchor insertion through a percutaneous Port of Wilmington portal (Fig. 14.13). Usually, we delay passing the second suture from this posterior anchor until the posterior labral repair is completed. In this way, suture passage may be performed with reference to the final suture passed during the posterior labral repair. Additionally, in order to maintain working space in the glenohumeral joint, the SLAP lesion sutures are not tied until the posterior labrum is repaired.

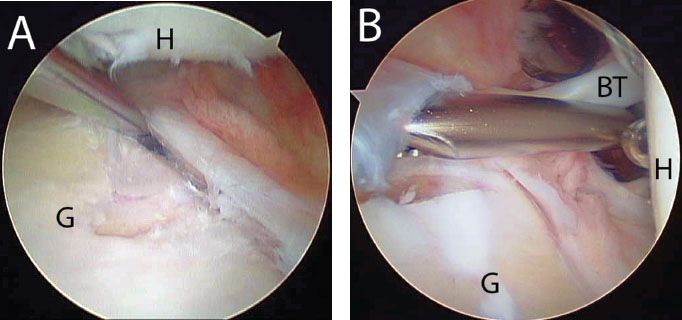

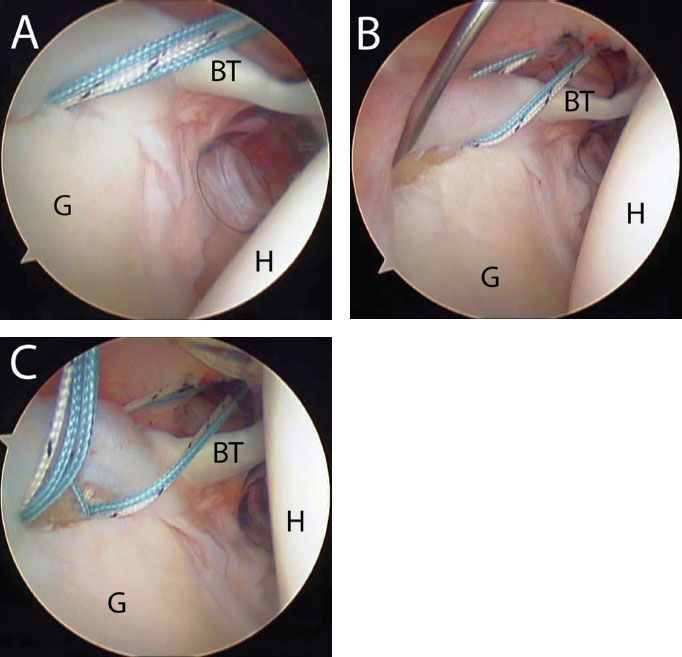

Figure 14.12 A: Right shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal, demonstrates a large posterior Bankart lesion that is mobilized for repair. B: Posterior viewing portal in the same shoulder demonstrates a SLAP lesion that extends posteriorly. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid; H, humerus.

Figure 14.13 A: Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal. An anchor has been inserted via an anterosuperolateral portal for a superior labral repair. B: In this case, the lesion extends posteriorly and there is also a posterior Bankart lesion (not seen). Thus, a Port of Wilmington portal is established using a spinal needle as a guide. C: View after placement of both anchors. Note: The three sutures have been passed, but not tied at this point because there is also a posterior Bankart lesion. The final suture is not passed until the posterior Bankart lesion is repaired because the location of the pass will be influenced by the posterior repair. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid; H, humerus.

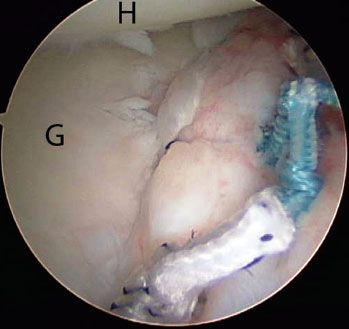

Figure 14.14 Right shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal, demonstrates a posterior Bankart lesion that was repaired with three anchors (compare to Fig. 4.12A). G, glenoid; H, humerus.

The posterior labrum is then repaired using the techniques as described above (Fig. 14.14). After the final posterior labrum suture is passed and tied, the final SLAP lesion suture from the anchor inserted through the Port of Wilmington portal is passed. The SLAP lesion sutures are then progressively tied, progressing from posterior to anterior (Fig. 14.15).

The posterior labrum is then repaired using the techniques as described above (Fig. 14.14). After the final posterior labrum suture is passed and tied, the final SLAP lesion suture from the anchor inserted through the Port of Wilmington portal is passed. The SLAP lesion sutures are then progressively tied, progressing from posterior to anterior (Fig. 14.15).

Posterior Labral Repair (Knotless Technique)

Any labral repair may be performed with a knotted or knotless technique, and thus may be performed for posterior labrum repair as well. The principles of labral repair are similar with mobilization, bone preparation, subsequent suture passage and anchor insertion. The steps for a knotless anchor were previously described in Chapter 12, “Repair of Anterior Instability without Bone Loss.” In the vast majority of cases, our preference is to tie knots during repair of a posterior labral tear.

Posterior Labral Repair with Reverse Remplissage

In some cases of posterior instability, a large reverse Hill-Sachs lesion may be encountered. This is usually present in patients with chronic locked posterior dislocations or in cases with a significant traumatic history (e.g., seizure disorder, electrical injury). Patients with positional posterior instability with ligamentous laxity usually do not present with significant reverse Hill-Sachs lesions.

With a shallow reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, it may be possible to do a reverse remplissage double-pulley technique with anchors placed transtendon to implant the subscapularis tendon into the humeral head defect. For large and deep reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, however, we caution against a reverse remplissage for two reasons. First, the thickness of the subscapularis tendon makes it difficult to inset the tendon into a deep lesion. Second, insetting the tendon into a large defect can result in an undesired change in the direction of the force vector produced by the subscapularis. In these cases, it is preferable to repair the middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments (which are disrupted in a large lesion) directly into the defect if possible. This creates a remplissage (filling) of the defect with the middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments rather than with the subscapularis tendon. This technique has the same advantage of creating an extra-articular defect, without the aforementioned potential negatives. Finally, for very large reverse Hill-Sachs lesions, a bone graft (e.g., iliac crest autograft) is required.

The decision as to which procedure to perform is guided by preoperative imaging and is ultimately based on arthroscopic appearance. Similar to our protocol for evaluating bone loss in anterior instability, we recommend a preoperative computed tomography scan with three-dimensional reconstructions. In addition, the posterior labral and the reverse Hill-Sachs lesions are evaluated arthroscopically before deciding on the definitive treatment. Unlike traditional Hill-Sachs lesions, reverse Hill-Sachs lesions are usually not accompanied by significant glenoid bone loss. Since these cases are rare, the pathology and position of reverse Hill-Sachs lesions are not as well defined as engaging Hill-Sachs lesions. Recommendations for implantation of the subscapularis tendon have been largely based on trauma literature regarding chronic locked posterior dislocations and may not be appropriate with today’s arthroscopic technology.

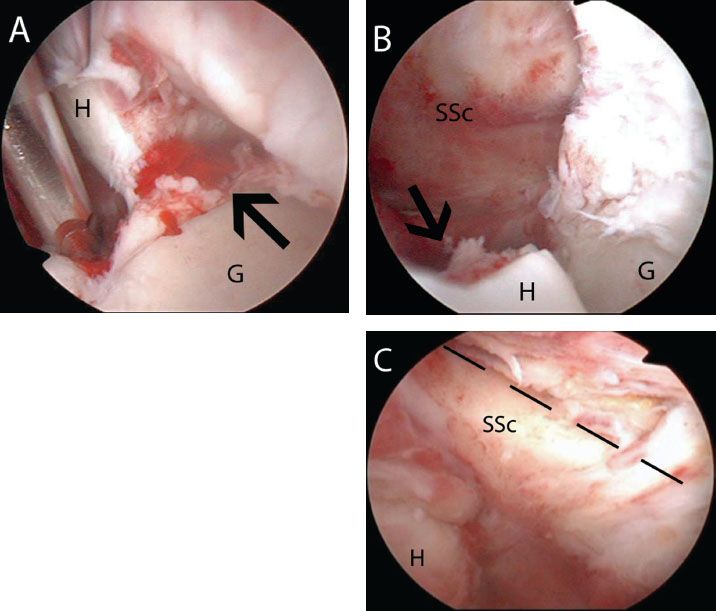

Using a 70° arthroscope from a posterior portal (after arthroscopic-assisted reduction of the posterior dislocation), an aerial view of the subscapularis tendon and the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion is obtained (Fig. 14.16). This view may be further enhanced by internal rotation, traction, and a posterior lever push similar to that used for subscapularis tendon repairs.

The bone bed in the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion is prepared in the same way as during subscapularis tendon repair, although in this scenario the upper border of the subscapularis tendon commonly obstructs direct access. Internal rotation will improve access, particularly to the inferior part of the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion.

Two anchors (5.5-mm BioComposite Corkscrew FT; Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) are inserted in the inferior and superior aspects of the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (Fig. 14.17). If a reverse remplissage is planned, both anchors are inserted percutaneously through the subscapularis tendon. For insetting of the glenohumeral ligaments, usually the superior anchor can be placed above the subscapularis tendon without a transtendon portal, but the inferior anchor always requires transtendon placement.

Figure 14.15 A: Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal. After a posterior Bankart lesion has been repaired, previously placed sutures for a superior labral repair are tied. Note: Soft tissue swelling above the superior labrum at this point in the procedure can be appreciated as well; this is why these sutures were placed at the beginning of the procedure. B: Final repair of the superior labrum. C: Profile view demonstrates the posterior extension. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid; H, humerus.

For reverse remplissage cases, knot tying is delayed at this point and attention is turned to the posterior labrum that is repaired using the previously described techniques. Then, attention is returned to the reverse remplissage. Using a double-pulley technique (see Chapter 4, “Complete Rotator Cuff Tears”), one suture from each anchor (of the same color) is then retrieved through the anterior portal. The sutures are then tied extracorporeally over an instrument and pulled into the joint using the anchors as pulleys. The matching suture limbs are then retrieved and a static knot is tied with a Surgeon’s Sixth Finger. The steps are repeated for the other suture pairs.

If an insetting of the inferior and middle glenohumeral ligaments is planned, we prefer to pass and tie these sutures immediately since swelling with subsequent surgery commonly limits visualization in the subcoracoid space. Sutures are passed through the inferior and middle glenohumeral ligaments with retrograde instruments. Static knots are then tied with a Surgeon’s Sixth Finger Knot Pusher (Fig. 14.18). After the insetting is complete, the posterior labrum is repaired using the techniques previously described.

TRIPLE LABRAL LESIONS

Triple labral lesions are combined tears of the labrum involving the anterior, posterior, and superior labrum. Loosely defined, tears of the anterior labrum are located from the 2 o’clock to 6 o’clock positions (Bankart lesion), tears of the posterior labrum (reverse Bankart lesion) are located from the 6 o’clock to 10 o’clock positions, and SLAP tears are located from the 10 o’clock to 2 o’clock positions. Although the principles of repair are relatively similar to isolated lesions, these complex tears require special consideration due to the extensive damage to the labrum circumferentially around the glenoid.

Figure 14.16 A: Left shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal, demonstrates a locked posterior glenohumeral dislocation with a large reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (black arrow). B: Posterior viewing portal in the same shoulder following arthroscopic-assisted reduction shows a large reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (black arrow). C: Up-close view demonstrates an intact subscapularis (superior border outlined by dashed black lines) insertion. Note: There is a large distance between the subscapularis tendon and the remaining humeral head. In this case, the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion is too large for a reverse remplissage. G, glenoid; H, humerus; SSc, subscapularis tendon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree