Ulnohumeral (Outerbridge-Kashiwagi) Arthroplasty

Loukia K. Papatheodorou

Alexander H. Payatakes

Filippos S. Giannoulis

Dean G. Sotereanos

DEFINITION

Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow is a relatively uncommon but disabling disorder that affects mostly middle-aged men who use the upper extremity in a repetitive fashion. Typically, patients are heavy manual workers or athletes. Osteoarthritis affects the elbow less frequently than other major joints.

Early stages of arthritis of the elbow may be characterized primarily by pain at the extremes of motion, with some loss of terminal extension and flexion. Some patients present with pain carrying an object with the arm in extension. More advanced stages may present with pain and crepitus throughout the range of motion, stiffness, or locking. Rotation of the forearm may be spared, depending on radiocapitellar involvement.

Radiographs show osteophyte formation on the coronoid and olecranon but relatively preserved joint space at the early stages. More advanced stages may be associated with significant joint space narrowing.

Multiple operative techniques have been described for treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the elbow: débridement arthroplasty, interposition arthroplasty, the Outerbridge-Kashiwagi procedure, arthroscopic débridement, and total elbow replacement.

Ulnohumeral (Outerbridge-Kashiwagi) arthroplasty was first described in 1978 and became popular a few years later. It is based on a posterior approach to the elbow, removal of any olecranon spur and bony overgrowth of the olecranon fossa, trephination of the fossa to expose the anterior capsule, and excision of the coronoid osteophyte.

Recent advancements allow the procedure to be performed with arthroscopic fenestration of the olecranon fossa, débridement, and removal of loose bodies.

ANATOMY

The elbow joint consists of three separate articulations: the ulnohumeral, the radiocapitellar, and the proximal radioulnar joints.

The elbow has two main functions: to position the hand in space and to stabilize the upper extremity for motor activities and power.

The normal range of elbow flexion-extension is 0 to 150 degrees, whereas normal forearm pronation-supination is 80 degrees of each.

A 100-degree flexion-extension arc of motion (30 to 130 degrees) is required for normal activities of daily living. Functional forearm rotation is quoted as 100 degrees (50 degrees pronation and 50 degrees supination).

The condyles articulate at the elbow joint, as the trochlea medially and the capitellum laterally. The articular surface is titled about 30 degrees anterior to the axis of the humeral shaft and aligns in approximately 6 degrees of valgus.

The coronoid fossa and the olecranon fossa, just proximal to the articular surface, accommodate the coronoid process and olecranon process of the ulna in the extremes of flexion and extension, respectively.

The olecranon and coronoid process coalesce to form the greater sigmoid notch, the main articulating portion of the proximal ulna. It is often not completely covered with articular cartilage centrally.

PATHOGENESIS

Symptomatic osteoarthritis of the elbow has been found to affect about 2% of the general population and represents only 1% to 2% of all patients diagnosed with degenerative arthritis.

It has a predilection for males, with a ratio of 4:1 or 5:1. It is most commonly seen in middle-aged and older patients.

The majority of patients experience symptoms in their dominant extremity.

The exact etiology of primary degenerative elbow arthritis is still unknown. It is generally attributed to overuse. About 60% of patients report employment or hobbies/sports requiring repetitive use of the limb. The few younger patients who present likely have a predisposing condition such as osteochondritis dissecans.

There are characteristic pathologic changes that occur within the elbow joint: osteophyte formation on the olecranon, olecranon fossa, coronoid, and coronoid fossa.

In early stages, the joint space is relatively well preserved. The periarticular bone is typically sclerotic.

Loose bodies frequently develop within the joint causing clicking or locking of the elbow.

Capsular fibrosis and contracture of the anterior capsule contribute to loss of extension.

NATURAL HISTORY

Early stages of primary osteoarthritis of the elbow are characterized by pain at the extremes of motion and some loss of terminal extension and flexion. As the severity of the arthritis progresses, pain and stiffness increase.

Surgical intervention is indicated when symptoms do not improve with nonoperative management.

As osteoarthritis is a progressive disease, symptoms may recur over time, typically in the form of impingement pain and flexion contracture.

Prognostic factors include the etiology of arthritis, the degree of motion loss, mid-arc versus end-range discomfort, the presence of loose bodies, mechanical symptoms, and the presence or absence of cubital tunnel syndrome.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The typical patient with primary degenerative elbow arthritis is a man older than 45 years of age, exposed to repetitive manual labor, and presenting with pain at the end ranges of motion, especially in extension.

Younger patients may provide a history of sports such as weightlifting, boxing, and other throwing-intensive activities. Arthritic elbows in athletes frequently will include a spectrum of pathologic changes, such as loose bodies and bone spurs.

Some patients report a history of chronic use of crutches or a wheelchair.

The chief complaint is pain, especially in terminal extension as a result of mechanical impingement.

Patients usually hurt while carrying objects with the elbow in full extension.

The intensity of pain is mild to moderate and only occasionally is described as severe.

Pain is usually not noted in the midrange of motion until later stages of arthritis.

Loss of motion is another common presenting symptom.

Loss of extension is often the result of posterior olecranon and humeral osteophytes and/or anterior capsule contracture.

Loss of flexion is secondary to osteophytes on the coronoid or its fossa and/or loose bodies.

Supination-pronation is preserved or is only minimally restricted, owing to limited involvement of the radiocapitellar joint.

Catching or locking may be present with articular incongruity or when loose bodies are present.

Crepitus may be present throughout the range of motion.

Swelling may occur but is not typical.

Ulnar nerve symptoms may also be present, owing to excessive osteophyte formation. They should actively be sought out because they may influence treatment decisions and even direct the surgical approach.

Physical examination may reveal a positive Tinel sign and a positive elbow flexion test, with decreased sensation and weakness in the ulnar nerve distribution. Cubital tunnel syndrome may be present in up to 20% of patients.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

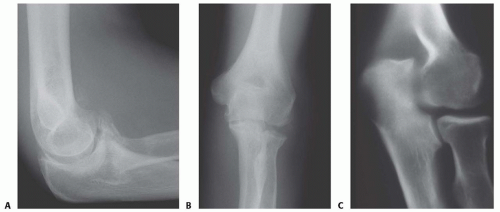

Anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique radiographs (FIG 1) are diagnostic and illustrate characteristic features of the condition.

The AP view should be taken with the beam perpendicular to the distal humerus for distal humerus pathology and perpendicular to the radial head for proximal forearm pathology. These views will show ossification and osteophyte formation of the olecranon and coronoid fossae.

The lateral view should be taken in 90 degrees of flexion with the forearm in neutral rotation. This view will show an anterior osteophyte on the coronoid fossa and process and a posterior osteophyte on the olecranon fossa and process.

The lateral oblique view provides better visualization of the radiocapitellar joint, medial epicondyle, and radioulnar joint.

The medial oblique view provides better visualization of the trochlea, olecranon fossa, and coronoid tip.

A cubital tunnel view may be useful if there is ulnar nerve symptomatology.

Computed tomography or a lateral tomogram are helpful for preoperative planning to assess the presence and location of loose bodies and subtle osteophyte formation (especially in earlier stages).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Posttraumatic arthritis

Rheumatoid (inflammatory) arthritis

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative treatment may be helpful in early stages.

Patients should limit activities that require heavy elbow use.

Physical therapy is used to maintain range of motion and strength. Modalities such as heat and cold may be effective.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can decrease pain and are of some value. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections may also improve symptoms, but their benefits are usually temporary.

Avoidance of pressure on the cubital tunnel and avoidance of prolonged elbow flexion are recommended if ulnar nerve symptoms are present.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical treatment is indicated when symptoms do not improve with appropriate nonoperative management.

The procedure is indicated in patients with pain in terminal extension or flexion (or both), radiographic evidence of coronoid or olecranon osteophytes (or both), ulnar neuropathy, and functional limitations due to pain or loss of motion.

The procedure is contraindicated in patients with pain throughout the entire arc of motion, marked limitation of motion with an arc of less than 40 degrees, or severe involvement of the radiocapitellar or proximal radioulnar joints.

The arthroscopic technique is relatively contraindicated in patients with previous elbow trauma or ulnar nerve transposition because of altered anatomy and potential risk of injury to adjacent neurovascular structures.

Preoperative Planning

It is very important to carefully review all radiographs (AP, lateral, oblique) before surgery to assess the severity of arthritic changes and evaluate for the presence of loose bodies. Computed tomography may assist in this evaluation. Care should be taken not to overlook any loose bodies, as these may lead to persistent mechanical symptoms postoperatively.

Specific attention should be paid to the presence of ulnar nerve pathology. If present, this must be addressed at the time of the procedure.

Positioning

Open or arthroscopic technique

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the elbow flexed at 90 degrees and resting on an armrest.

Open technique

Alternatively, the patient may be placed supine with a sandbag underneath the scapula. The elbow is flexed at 90 degrees and brought across the chest. The patient is rotated about 35 degrees for better access to the posterior aspect of the affected elbow.

APPROACH

Open technique

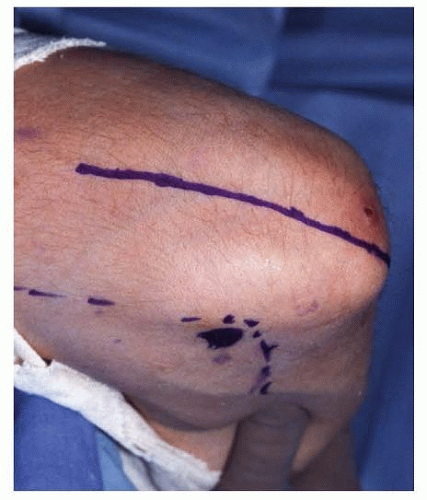

A posterior approach is used. The incision is longitudinal, starting 6 to 8 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon and extending 4 cm distal to the olecranon (FIG 2).

Dissection is carried down to the triceps fascia.

The triceps tendon can be split or reflected. In the original description, the triceps muscle is split along the midline, exposing the posterior aspect of the elbow to the lateral and medial supracondylar ridges. Alternatively, the medial margin of the triceps tendon may be reflected from the olecranon.

The decision to reflect or to split the tendon is determined based on the size of the distal aspect of the triceps and the need to explore and decompress the ulnar nerve. If the muscle is very bulky, reflection will not provide adequate exposure.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Open Humeral Arthroplasty

Exposure

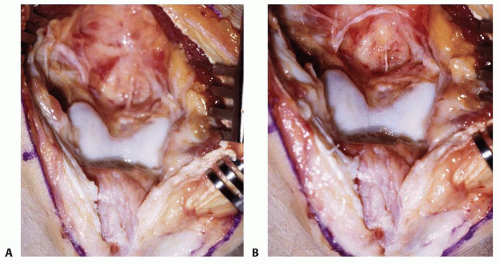

After skin incision, the subcutaneous tissue is reflected from the medial aspect of the triceps.

The ulnar nerve is identified and decompressed at the cubital tunnel if there is evidence of ulnar nerve pathology.

The triceps muscle-tendon unit is split longitudinally or reflected.

The triceps is elevated from the posterior aspect of the distal humerus by blunt dissection using a periosteal elevator.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree