Ulnohumeral Arthroplasty

Bernard F. Morrey

Samuel A. Antuña

INTRODUCTION

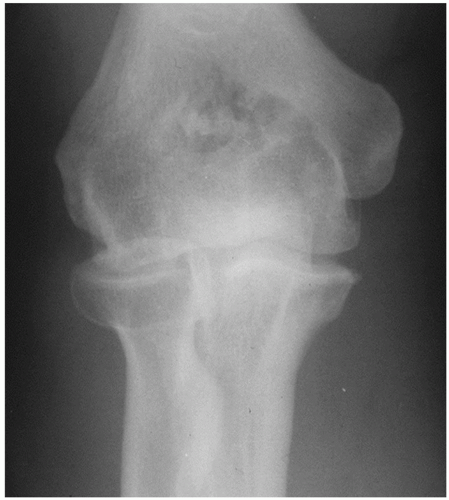

The existence of degenerative arthritis involving the elbow is well recognized (1,2 and 3). The process typically limits extension to a minimal or moderate extent. Most symptomatic is impingement pain with terminal extension and, less commonly, terminal flexion with or without ulnar nerve involvement. A debridement procedure termed ulnohumeral arthroplasty has proven to be effective and reliable for such conditions, especially if ulnar nerve involvement is an issue or the disease is associated with a marked hypertrophic response (Fig. 20-1). With increasing experience, we have come to realize the significance of ulnar nerve involvement in those with degenerative arthritis especially with a high degree of flexion loss (4).

PRESENTATION

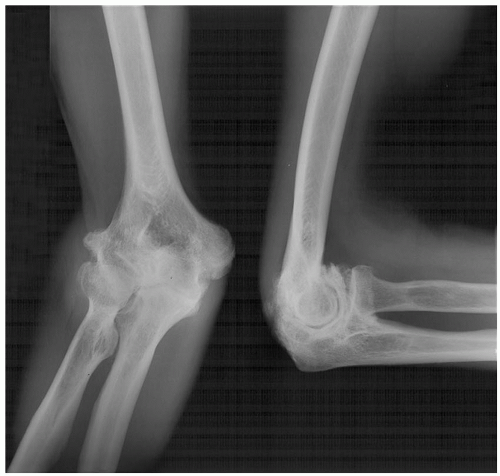

The patient with primary osteoarthritis is the ideal candidate for ulnohumeral arthroplasty. The characteristic of this process is that it occurs predominantly in males by at least a 5-to-1 ratio (3,5,6). The mean age is approximately 55 years, range 25 (uncommon) to 65. Chief complaint is terminal extension pain; a painful midarc is uncommon. Radiohumeral involvement occurs in approximately 50%, and in some, this articulation may be disproportionately advanced and the focus of most symptoms (Fig. 20-2). Loose body formation occurs in approximately 30%. Over half of the individuals will have an occupation or lifestyle associated with repetitive use, such as a carpenter, a laborer, or individuals requiring a wheelchair or crutches for ambulation (6). The dominant side is affected in over half the patients, and about 25% will have some changes in the contralateral elbow. About one in four will have symptoms of ulnar nerve irritation.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

This procedure is particularly indicated in patients presenting with terminal extension pain, radiographic evidence of coronoid or olecranon osteophytes, and ossification of the olecranon foramen. If ulnar nerve symptoms are present, the nerve is inspected and decompressed in situ. If ulnar neuropathy is present, or if flexion motion is less than 90 degrees, the nerve is decompressed but not translocated.

This procedure is contraindicated in the patient with pain throughout the arc of motion, marked limitation of motion with an arc of less than 30 to 40 degrees, or severe radiohumeral involvement indicating an advanced and generalized process. Isolated symptoms of catching associated with loose bodies are best dealt with by arthroscopy (7,8). If high-grade (less than 45-degree arc present) motion loss is the principal concern, we prefer the column decompression procedure (9) (Chapter 19). In those with complaints of motion loss as well as impingement pain, we also prefer the column procedure or perform the debridement through the scope (Chapter 15). If the ulnar nerve is symptomatic, as in those with less than 90-degree flexion, we decompress the ulnar nerve.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

It is most important to properly select patients for this procedure. This operation is not primarily designed to gain motion but rather to relieve the pain associated with the impingement

arthritis, especially in terminal extension. If the impingement is associated with mild osteophyte formation, an arthroscopic debridement has been effective in the hands of the experienced (7,8). However, particular attention should be paid to the presence of ulnar nerve symptoms. This must be addressed at the time of decompression and prompts this open rather than the arthroscopic procedure.

arthritis, especially in terminal extension. If the impingement is associated with mild osteophyte formation, an arthroscopic debridement has been effective in the hands of the experienced (7,8). However, particular attention should be paid to the presence of ulnar nerve symptoms. This must be addressed at the time of decompression and prompts this open rather than the arthroscopic procedure.

Since approximately 30% of the patients will have loose bodies, it is important to assess this before surgery, in addition to routine anterior-posterior and lateral radiographs. A CT scan may be useful to define the precise size of the osteophytes as well as allows identity of any loose bodies. Specific care is taken not to overlook any loose bodies, as these may cause mechanical symptoms later. Other imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging are expensive and totally unnecessary.

FIGURE 20-1 In those with extensive hypertrophic changes, the UHA or a column procedure is preferred over an arthroscopic debridement. |

SURGERY

With the patient supine and a sandbag under the shoulder, general anesthesia is administered and the elbow is brought across the chest.

Exposure

A posterior incision courses just medial to the tip of the olecranon. This extends distally approximately 4 cm and proximally about 6 cm (Fig. 20-3). The subcutaneous tissue is reflected from the medial aspect of the triceps.

The ulnar nerve is identified at the cubital tunnel and carefully inspected. Its possible involvement with an osteophyte or from degenerative changes in the medial epicondylar region should be assessed before surgery (Fig. 20-4). The nerve has been a source of irritation for a growing number of patients, so we have a lower threshold to decompress than we once had. The nerve is carefully inspected, but the cubital tunnel retinaculum is released in all instances when doing this procedure.

Joint Exposure Two approaches to the posterior joint are possible. A simple triceps splitting technique was originally described and is still used in very muscular individuals (Fig. 20-5). Otherwise, approximately one-third to one-half of the triceps attachment may be elevated from the medial tip of the olecranon releasing Sharpey fibers by sharp dissection (Fig. 20-6). The triceps is elevated from the posterior aspect of the distal humerus by blunt dissection using a periosteal elevator. The capsule is excised, and any loose bodies are removed from the posterior compartment.

Debridement The tip of the olecranon is identified (Fig. 20-7). Usually, there is a prominent osteophyte present that may extend across the joint and into the medial and lateral margins of the greater sigmoid notch. The tip of the olecranon with the osteophyte is resected first using an oscillating saw to define the exact amount to be resected. A 13-mm osteotome is used to complete the resection (Fig. 20-8), and the olecranon process with its osteophyte is removed (Fig. 20-9). The level should be such that the posterior aspect of the ulna is flush with the midportion of its articulation. The orientation of the osteotome should be parallel to each face of the trochlea rather than directed straight across the olecranon to avoid damage to the trochlea (Fig. 20-10).

An 18- to 20-mm-diameter trephine (Cloward) is then used to open the ossified olecranon fossa (Fig. 20-11). Often, there are osteophytes originating from both the medial and the lateral column. Proper

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree