Triple Innominate Osteotomy

Dennis R. Wenger

Maya E. Pring

Vidyadhar V. Upasani

DEFINITION

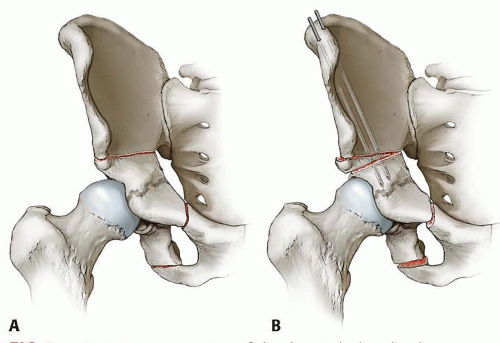

Triple innominate osteotomy (TIO) is a surgical procedure that includes osteotomy of the ilium, ischium, and pubis, allowing rotation of the acetabulum around the femoral head (FIG 1). This greater freedom of rotation allows it to be used in more severe cases where the Salter innominate osteotomy would not provide enough rotation to cover the femoral head.

Because the procedure does not damage the triradiate cartilage, it can be used in skeletally immature patients without the risk of disrupting acetabular growth. The volume of the acetabulum remains constant, but the weight-bearing surface is reoriented to improve femoral head coverage.

TIO is most commonly used for correction of acetabular dysplasia. Dysplasia may be a primary disorder or result from incomplete treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH).5 It is also seen as a result of neuromuscular conditions such as cerebral palsy, myelomeningocele, Down syndrome, Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome, etc.

TIO can also be used to improve coverage/containment of a malformed femoral head and for a combination of acetabular and femoral head deformities such as in patients with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease19 (Perthes disease), avascular necrosis (AVN), epiphyseal dysplasia, or an irregular femoral head resulting from a previous septic hip.

The TIO has the advantage of maintaining hyaline cartilage contact between the femoral head and acetabulum.17 This is in contrast to other procedures sometimes used to correct severe hip dysplasia/instability (shelf procedure, Chiari osteotomy) which must rely on fibrocartilage to maintain a joint surface.

ANATOMY

The acetabulum is formed by the ilium, ischium, and pubis, which in the immature pelvis are joined by the triradiate growth cartilage. This complex, triflanged growth center allows the acetabulum to grow properly, providing a deep, stable hip joint.

The femoral head should be covered by the roof of the acetabulum. The center-edge angle of Wiberg (angle between a line from the center of the femoral head to the lateral edge of the acetabular roof and a vertical line drawn through the center of the femoral head) should be greater than 25 degrees.20

Lateral subluxation of the femoral head can be measured as the percent of the femoral head not covered by the acetabulum.

The acetabulum should be concave with a transverse sourcil (“eyebrow”—French) above the femoral head. Patients with hip dysplasia frequently have a very flat acetabulum with an up-turned sourcil. This results in shear forces on the joint that leads to early degenerative joint disease.

The normal hip joint has a spherical femoral head that is congruent with a well-formed acetabulum. Sphericity of the femoral head can be measured with Mose templates (concentric circles). Deformity in Perthes or AVN can be measured as a percentage of the femoral head (lateral pillar) that has collapsed when compared to the contralateral side.7 Conditions that change femoral head sphericity lead to abnormal hip development and increased wear patterns within the joint.

PATHOGENESIS

Hip dysplasia: Many factors play a role in the etiology of hip dysplasia. The high concordance between twins and studies noting that babies with parents or siblings with dysplasia have a much higher DDH incidence than the general population confirm a genetic component. Mechanical factors also contribute to the risk for dysplasia. First babies and babies that are large have a higher risk thought to be secondary to inadequate space in the uterus during development. There also appears to be a hormonal component, as females and babies with increased joint laxity are at greater risk of hip dysplasia.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease: The etiology of Perthes disease remains obscure and can be thought of as idiopathic AVN of the hip in childhood. Some have postulated a deficiency in protein C leading to a hypercoagulable state with thrombosis triggered by prothrombotic insults.11

As most Perthes patients have a delayed bone age, some have suggested that Perthes may represent a form of epiphyseal

dysplasia. Delayed skeletal maturation, is a routine finding in a typical Perthes case. The delay in maturation of the femoral head preossific nucleus may not adequately protect the vessels that ascend the femoral neck to the epiphysis, predisposing to AVN.

NATURAL HISTORY

Hip dysplasia

Untreated hip dysplasia is the leading cause of premature hip arthritis that results in early total hip replacement.

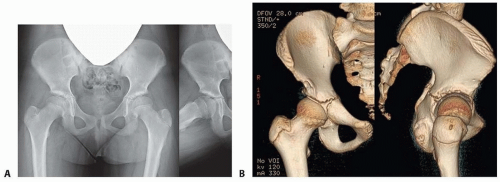

Abnormal sheer stresses on the hip lead to early osteoarthritis, and the more severe the dysplasia, the more likely the development of arthritis (FIG 2).

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

The natural history for younger patients (younger than age 8 years at onset) and patients with milder disease (Herring A classification) is more benign with little long-term disability.

Children who are older at onset and who have more severe disease (Herring B or C classification) are more likely to develop femoral head deformity which predisposes to early osteoarthritis.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Hip dysplasia

Hip dysplasia is often asymptomatic in childhood and adolescence. Patients may have decreased abduction on examination or pain with internal rotation of the hip.

When symptoms are present, they are likely due to increased shear stresses, labral damage, and later to osteoarthritis. The pain is usually groin pain rather than lateral or trochanteric pain.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Perthes may present as hip or knee pain. Early pain may be episodic.

Patients with severe disease may have subluxation and more severe pain. A Trendelenburg gait is often noticed.

Decreased abduction can be mild or severe. A marked loss of abduction with the hip in the fully extended position (pelvis rotates rather than hip abducting) suggests hinge abduction and is a bad prognostic sign.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

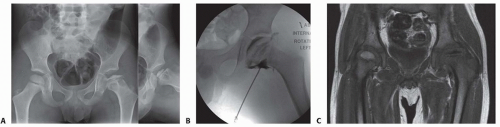

Plain radiographs: Anteroposterior (AP) and frog lateral views provide two orthogonal views of the femoral head. However, to get two views of the acetabulum, a false-profile x-ray should be taken in addition to the AP view (FIG 3A). Always image both hips (to allow comparison).

We advise a surgeon performed arthrogram to evaluate the hip deformity and to assess for hinge abduction as well as the desired limb position following surgical correction (FIG 3B).

Three-dimensional (3-D) computed tomography (CT) scans with reconstructions provide a better understanding of pathologic bony anatomy.2

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with arthrogram helps to evaluate the labrum and joint space (FIG 3C).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hip dysplasia

DDH

Dysplasia secondary to neuromuscular disease (cerebral palsy, myelomeningocele, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, etc.)

Dysplasia, subluxation secondary to syndromes (Down syndrome)

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

AVN secondary to Perthes disease

AVN secondary to steroid use, chemotherapy, metabolic disruption, infection, sickle cell disease

Epiphyseal dysplasia with poor femoral head coverage

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Hip dysplasia

From infancy to childhood (up to 18 months of age), if the hip is located within a dysplastic acetabulum, a Pavlik harness or abduction orthosis can be worn to treat the dysplasia.3

From age 18 months to 5 years, abduction bracing has not been found to predictably improve dysplasia, although nighttime brace use is occasionally recommended. Most advise monitoring during this period with hope that the acetabular growth centers will mature and correct the dysplasia.14

Older children with hip dysplasia are typically asymptomatic until the hip begins to have degenerative changes or a labral tear. Anti-inflammatory medications and activity modification can be used to decrease pain, but these do not correct the underlying problem, and by masking symptoms may delay surgical correction.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Children younger than 8 years and patients with hips classified as Herring A can be treated conservatively with predictable results. Conservative treatment includes activity modification and observation, abduction exercises, abduction bracing, and percutaneous adductor longus lengthening followed by Petrie casting (FIG 4) or bracing to maintain abduction.

FIG 4 • Petrie casts, which provide containment of the femoral head, are often used in patients with Perthes disease in preparation for TIO.

Older children and those with Herring B and C hips require prolonged Petrie casting or bracing (rarely practiced) or surgical containment.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Hip dysplasia

Dysplasia before age 4 years is treated nonoperatively unless the hip is dislocated and requires open reduction or the dysplasia is very severe.

Patients aged 4 to 10 years can be treated with an acetabular redirecting osteotomy16 or an osteotomy that bends through the triradiate cartilage.12

From the age of about 10 years until triradiate cartilage closure, a TIO is preferred for correction of dysplasia. Once the triradiate cartilage closes, TIO can still be performed but a periacetabular osteotomy may be preferred because the posterior column remains intact, providing greater stability and earlier weight bearing.4

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Children older than age 6 to 8 years or with more severe disease can be treated with a variety of surgical procedures aimed at containing the capital femoral epiphysis during the early fragmentation phase when the biologically plastic femoral head is at risk for subluxation, hinge abduction, and the development of permanent femoral head deformity. The simplest surgical treatment is adductor lengthening followed by Petrie casting or bracing. This can be used alone for very mild cases or in preparation for containment surgery.

Formal containment procedures include varus proximal femoral osteotomy designed to direct the capital femoral epiphysis into the acetabulum. A Salter innominate osteotomy can also be performed, but Rab15 has clarified that the degree of acetabular rotation achieved with the Salter procedure is often not enough to cover the femoral head in more severe Perthes disease. A combined femoral and Salter procedure may be a better choice.

TIO, which rotates the entire acetabulum around the femoral head, allows containment in more severe cases18 while avoiding the problems of femoral osteotomy (limp, limb shortening). A shelf (labral support) osteotomy or Chiari procedure may be a better choice for a severely deformed femoral head that cannot be congruently centered in the acetabulum.

Preoperative Planning

Hip dysplasia

Radiographs and a 3-D CT scan (if available) helps to better understand the nature and location of the acetabular deficiency.

Typical dysplasia patients have an anterolateral deficiency.

Children with neuromuscular disorders such as cerebral palsy, due to muscle imbalance around the hip joint and flexion contracture, often have a posterior deficiency.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree