Triple Arthrodesis

R. Justin Mistovich

David A. Spiegel

James J. McCarthy

DEFINITION

Triple arthrodesis involves fusion of the talocalcaneal, calcaneocuboid, and talonavicular joints. The procedure is most commonly indicated for salvage in severe, rigid deformities of the hindfoot which are unresponsive to less invasive methods of treatment.

This procedure is typically considered in adolescents but has been reported in children as young as 8 years of age.

ANATOMY

Joints of the hindfoot: the ankle, subtalar, talonavicular, and the calcaneocuboid joints

Ankle joint motion: plantarflexion and dorsiflexion. Dorsiflexion is associated with outward deviation of the foot, whereas plantarflexion is associated with inward deviation.

Subtalar (talocalcaneal) joint components: anterior, middle, and a posterior facet. The anterior and middle facets are confluent in a subset of patients. Although there is considerable variation, this joint is usually oriented 23 degrees medially in the transverse plane and 42 degrees dorsally in the sagittal plane. The subtalar joint thus functions as a hinge along an inclined axis and serves as the linkage between the ankle and the distal articulations of the foot. During the gait cycle, the subtalar joint is everted at heel strike and then inverts progressively until push off.

The transverse tarsal joints: These include the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints. When the calcaneus is everted, these joints become parallel, and there is greater flexibility at the articulation. This aids in shock absorption during initial contact and early stance phase. In contrast, the transverse tarsal joints become nonparallel and more rigid when the calcaneus is inverted. Functionally, the calcaneus becomes inverted during late stance phase, which locks the transverse tarsal joints and provides a rigid lever for push off.

Muscles crossing the ankle and subtalar joints:

Ankle plantarflexors: gastrocnemius and soleus, tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus

Ankle dorsiflexors: tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, extensor hallucis longus

Subtalar inverters: tibialis anterior and posterior, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus

Subtalar everters: peroneus longus, brevis, tertius, extensor digitorum longus, extensor hallucis longus

PATHOGENESIS

Congenital conditions causing foot deformities: clubfoot, vertical talus, tarsal coalition

Neuromuscular diseases causing foot deformities: cerebral palsy, polio, myelomeningocele, hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies. The etiology involves muscle weakness and/or imbalance.

The most common deformities are equinovarus, equinovalgus, and cavovarus. Calcaneovalgus, calcaneovarus, calcaneocavus, and equinocavus may also be seen. This spectrum of deformities may result from soft tissue contractures, from bony malalignment, or from both.

Although some deformities have a structural component at birth, the majority develop gradually, are initially flexible, and only become fixed or rigid over time. Although a loss of passive motion may result from contracture of the soft tissue elements, progressive adaptive changes in the osteocartilaginous structures subsequently result in fixed bony malalignment.

Causes of equinovarus deformity: This deformity is present at birth in a congenital clubfoot. Although the etiology/pathogenesis of congenital clubfoot remains debated, it is most likely multifactorial. Equinovarus deformity may result from spastic muscle imbalance in patients with cerebral palsy (most often spastic hemiplegia) or flaccid muscle imbalance in poliomyelitis. The pathogenesis in neuromuscular diseases involves muscle imbalance (strong inversion/plantarflexion and weak eversion/dorsiflexion).

Causes of equinovalgus deformity: This deformity is most common in patients with a congenital vertical talus or cerebral palsy (most commonly spastic diplegia).

A valgus deformity of the hindfoot is common in patients with a tarsal coalition.

Pathogenesis of the cavovarus foot: This deformity is most commonly associated with hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies (Charcot-Marie-Tooth) and results from muscle imbalance. Weakness of the tibialis anterior relative to the peroneus longus is associated with plantarflexion of the first ray. This results in forefoot valgus, a deformity which is initially flexible. Over time, a contracture of the plantar fascia and neighboring intrinsic muscle groups develops. To compensate for forefoot valgus, the hindfoot aligns in varus during stance phase. Over time, both the forefoot valgus and the hindfoot varus become rigid. The hindfoot also appears to be in equinus due to plantarflexion of the midfoot on the hindfoot. A common mistake is to assume that the equinus occurs at the ankle and to perform a tendo Achilles lengthening.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history depends on the underlying disease process. Deformities associated with the neuromuscular diseases will usually progress (and become rigid) over time and will often recur despite treatment due to the underlying disease process.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients present with an abnormality or change in appearance of the foot, gait disturbance, pain in the region of the hindfoot, difficulties with shoe wear, or more than one of these. Although the deformities treated by triple arthrodesis may be diagnosed from birth to adolescence, and have often been treated previously, we focus on the older child or adolescent.

The history focuses on the presence of symptoms including functional limitations, cosmetic concerns, shoe wear, and on the family history (similar deformities, neuromuscular diseases) and previous treatment.

A detailed history is especially important in children of walking age, as a foot deformity may be the first clue to the presence of an underlying neuromuscular problem. Although unilateral foot deformities may be seen with tethering of the spinal cord (or other problems such as a spinal cord tumor), bilateral deformities may be the initial finding in patients with a hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy.

The location and character of pain should be determined, in addition to the activities which produce discomfort.

A comprehensive physical examination is required. The spine should be examined to rule out any deformity or evidence of an underlying dysraphic condition, and a careful neurologic examination should be performed. The extremities are evaluated for alignment, limb lengths, and range of motion. Observational gait analysis should be performed. The shoes should be inspected for patterns of wear, which indicate weight distribution during stance phase.

The physical examination of the foot and ankle: Focus on the skin, identifying the presence and location of callosities and points of tenderness. Examine the overall appearance in both the weight bearing and non-weight bearing positions, visualizing the relationship between the forefoot and hindfoot. Check the range of motion of the hindfoot joints. Perform a complete neuromuscular assessment.

Tests to perform during the physical examination include the following:

Range of motion at the ankle joint (plantarflexion and dorsiflexion) to diagnose and determine the magnitude of equinus contracture

Range of motion at the subtalar joint (inversion and eversion), which quantifies motion at the subtalar joint. Generally, the amount of inversion is twice the amount of eversion. The total range is 20 to 60 degrees.

Range of motion at the transverse tarsal joints

Relationship between forefoot and hindfoot alignment, which identifies any coexisting deformity of the forefoot, either varus (dorsiflexion of the medial column relative to the lateral column) or valgus (plantarflexion of the medial column relative to the lateral column)

Coleman block test, which determines if hindfoot varus is flexible or rigid

Manual muscle testing, which assesses relative strengths of motor units across the ankle and subtalar joints. This helps to diagnose muscle imbalance and to plan tendon transfers if appropriate.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Imaging studies complement the history and physical examination, and plain radiographs, specifically in a weight-bearing position are required in all cases. In addition to a standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiograph of the foot, a standing AP of the ankle should be obtained to determine whether the deformity affects the ankle joint, the subtalar joint, or both locations. Other imaging modalities such as a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be required in selected cases.

Plain radiographs are used to evaluate bone and joint morphology, and measuring the angular relationships between the tarsal bones (or segments of the foot) help to further define both the location and the magnitude of deformities.

On the standing AP radiograph, measurements include the talocalcaneal (Kite) angle (10 to 56 degrees) and the talo-first metatarsal angle (range −10 to +30 degrees). For the AP talocalcaneal angle, values less than 20 degrees suggest hindfoot varus, whereas an angle greater than 40 to 50 degrees suggests hindfoot valgus. For the talo-first metatarsal angle, values less than −10 degrees indicate forefoot varus and values greater than +30 degrees indicate forefoot valgus.

On the standing lateral radiograph of the foot, measurements include the lateral talocalcaneal angle, the tibiocalcaneal angle, and the talo-first metatarsal angle. For the lateral talocalcaneal angle (range 25 to 55 degrees), values greater than 55 degrees indicate hindfoot valgus or calcaneus, whereas values less than 25 to 30 degrees indicate hindfoot varus or equinus deformities. For the tibiocalcaneal angle (55 to 95 degrees), values greater than 95 degrees suggest equinus, whereas those below 55 degrees are suggestive of calcaneus. For the talo-first metatarsal, or Meary angle (0 to 20 degrees), values greater than 20 degrees indicate midfoot equinus (cavus), whereas values less than 0 degree indicate midfoot dorsiflexion (midfoot break). The angle of the calcaneus relative to the horizontal axis (calcaneal pitch) is increased with calcaneus or calcaneocavus or with cavovarus deformities.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Equinovarus: congenital clubfoot, poliomyelitis or other flaccid weakness/paralysis, spastic hemiplegia

Equinovalgus: congenital vertical talus, spastic diplegia or quadriplegia, tarsal coalition, flexible flatfoot with tight tendo Achilles

Cavovarus: hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies, poliomyelitis or other flaccid weakness/paralysis, myelomeningocele

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The goals of nonoperative treatment are to achieve and/or maintain mobility and normal alignment. The specific treatments are based on the underlying disease process.

Options include physical therapy, injection of botulinum A toxin, serial casting, and orthoses.

Physical therapy is directed toward improving range of motion and improving strength.

Serial casting may help to improve range of motion.

Botulinum toxin injections result in a chemical denervation of the muscle group lasting for 3 to 8 months. Botox has been used most frequently in patients with cerebral palsy to decrease spasticity and reduce dynamic muscle imbalance. Such treatment may prevent or delay the need for surgical intervention in patients with spastic equinovarus or equinovalgus.

Orthoses may be used to maintain alignment during ambulation or as a nighttime splint to prevent the development of contractures. The deformity should be passively correctable. Foot orthoses such as the University of California Biomechanics Laboratory (UCBL) may help to control varus/valgus alignment of the hindfoot during ambulation. An ankle-foot orthosis improves prepositioning of the foot during swing phase, provides stability during stance phase, and can be used as a night splint.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical treatment is offered when nonoperative measures have failed to alleviate the symptoms. Triple arthrodesis is a salvage procedure or “last resort” for rigid deformities in older patients, many of whom have been previously treated by both nonoperative and operative strategies.

The procedure often requires removal of bony wedges. As such, careful preoperative planning is required to determine the appropriate size and location of these wedges. Triple arthrodesis shortens the foot, which may be cosmetically objectionable especially when the deformity is unilateral.

Arthrodesis transfers additional stresses to neighboring joints, which may result in degenerative changes and pain. Although there are reports of the procedure being successful in children as young as 8 years of age, it has been suggested that surgery should be delayed until the foot has reached adult proportions. One recent study concluded that growth rates were no different in those children treated before or after 11 years of age.14

The deformity should be of sufficient severity that soft tissue releases and osteotomies would be unlikely to achieve correction or when painful degenerative changes are observed in the joints of the hindfoot. Indications include the recurrent or neglected clubfoot, cavovarus associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, and severe equinovalgus deformities in patients with spastic diplegia.

The goal of surgery is to achieve a plantigrade foot by restoring the anatomic relationships between the affected bones and/or regions of the foot and to relieve pain.

Additional procedures may be required. An equinus deformity of the ankle will require a lengthening of the tendo Achilles at the time of triple arthrodesis. In patients with neuromuscular diseases, lengthening or transfer of tendons may be required to restore muscle balance and prevent further deformity. Recurrence of deformity may occur when coexisting muscle imbalance has not been treated.4, 27

A hindfoot arthrodesis should be avoided in patients with insensate feet, such as myelomeningocele.

Although triple arthrodesis has been performed without fixation, or with minimal fixation such as Kirschner wires or staples, fixation with staples or screws reduces the chances of correction loss and pseudarthrosis.

Preoperative Planning

Weight-bearing radiographs are used to evaluate the relationships between the tarsal bones, to identify any morphologic abnormalities and/or degenerative changes, and to identify the location of the deformity. These radiographs help to plan the location of wedge resections.

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position.

Approach

Several skin incisions have been described for triple arthrodesis, and the specific choice depends on the type of deformity and the previous experience of the surgeon. These include the single lateral or anterolateral approach, the medial approach, and a combined lateral and medial approach.

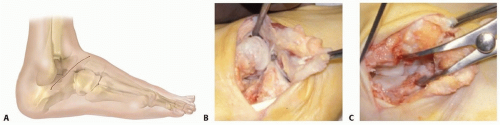

The lateral approach (Ollier) is used in triple arthrodesis for neglected clubfoot (FIG 1).

A medial approach has been used for the calcaneovalgus foot, especially if previous incision or surgery has made lateral aspect tenuous.

The Lambrinudi procedure is used for severe equinus deformity. A double-incision approach is used to do triple arthrodesis when no significant deformity is present.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Triple Arthrodesis for the Neglected Clubfoot (Modified Lambrinudi Procedure)

There are several unique features associated with the neglected clubfoot in adolescents which require special attention when performing a triple arthrodesis.8, 20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree