Trigger fingers are common tendinopathies respresenting a stenosing flexor tenosynovitis of the fingers. Adult trigger finger can be treated nonsurgically using activity modification, splinting, and/or corticosteroid injections. Surgical treatment options include percutaneous A1 pulley release and open A1 pulley release. Excision of a slip of the flexor digitorum superficialis is reserved for patients with persistent triggering despite A1 release or patients with persistent flexion contracture. Pediatric trigger thumb is treated with open A1 pulley release. Pediatric trigger finger is treated with release of the A1 pulley with excision of a slip or all of the flexor digitorum superficialis if triggering persists.

Key points

- •

Stenosing flexor tenosynovitis is a debilitating, common condition affecting both the adult and pediatric populations, causing catching, clicking, and locking of the digits.

- •

Several nonsurgical options are used, including anti-inflammatory medications, splinting, and/or local corticosteroid injections.

- •

Open A1 pulley release remains the gold standard of treatment, but percutaneous, in-office techniques have been established with similar success rates.

- •

Pediatric trigger finger and thumb have a distinct pathology, natural history, and treatment algorithm.

Adult trigger digit

Stenosing flexor tenosynovitis of the hand, commonly known as trigger finger, is a potentially debilitating condition characterized by catching, clicking, or locking of the fingers. The etiology is any pathology between the flexor sheath and the underlying tendons that impedes smooth gliding during flexion. Early epidemiologic studies found a 2.6% lifetime risk of developing trigger finger, with an increased incidence in certain systemic conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and inflammatory arthridities. Women are more affected than men and the thumb is the most commonly involved digit.

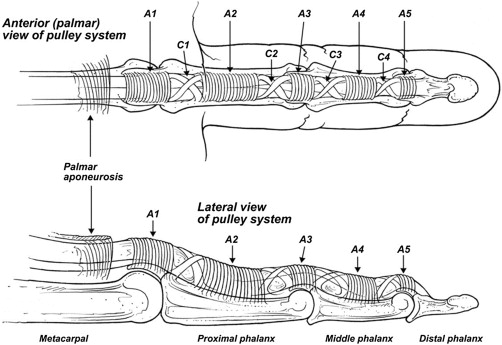

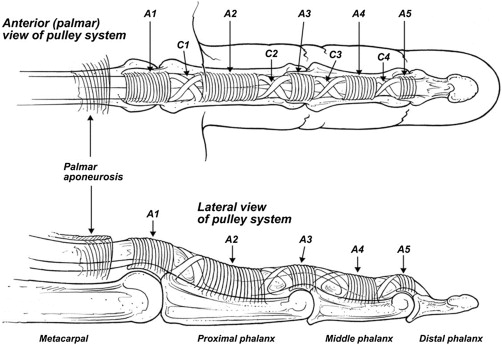

The flexor sheath, enveloping the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), is composed of 5 annular pulleys and 3 cruciate pulleys ( Fig. 1 ). In-between the sheath and the underlying tendon is a thin synovial membrane that decreases the friction during gliding. The etiology of trigger finger is chronic repetitive friction between the tendon and the A1 pulley, which imparts a high angular load on the underlying tendon during flexion. In the thumb, the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) enters the tendon sheath at a more acute angle, in contrast to the FDP and FDS tendons, providing a mechanical strength advantage; however, this is likely the reason it has the highest incidence of stenosing flexor tenosynovitis.

Histologic analysis of tissue biopsied from patients with trigger finger shows fibrocartilaginous metaplasia with positive staining for S-100 proteins, usually found in chondrocytes. Similarly, biopsies of tendons diagnosed with trigger finger demonstrate disrupted fibers and hypercellularity, with an increased number of chondrocytes and glycoaminoglycans. No significant amount of inflammatory cell or synoviocyte proliferation was discovered in these studies. These findings are consistent with tendinopathy and suggest that the term, flexor tenosynovitis , is actually a misnomer because there is no evidence of synovial inflammation. The term, flexor tendovaginosis , has been proposed to more accurately reflect the disease process.

Ultrasound examination in patients with symptomatic trigger finger has found that the A1 pulley is significantly thicker and stiffer than normal controls. Three weeks after corticosteroid injection, the thickness and stiffness return to values comparable with healthy A1 pulleys, whereas the cross-sectional area of the FDS and FDP tendons is unchanged. Whether the instigating factor behind the development of digit triggering is a pathologic pulley system or a pathologic tendon remains unclear. By the time clinical symptoms become noticeable, both the tendon and the pulley are likely involved.

The diagnosis of trigger finger is made based on clinical findings. The natural progression of symptoms is painless clicking, followed by painful triggering, and ultimately a flexed, locked digit. With more-advanced disease, patients may report pain radiating retrograde to the forearm. Although a patient may present with advanced symptoms in a single digit, the clinician must astutely examine all other digits because severe symptoms in 1 finger may mask early signs of triggering in other digits. It is prudent to treat all affected digits simultaneously regardless of severity. Further imaging or diagnostic studies are not necessary, unless unusual examination findings warrant ruling out concomitant conditions.

The Quinnell grading system, based on mechanical symptoms, is commonly used to classify trigger finger severity ( Table 1 ). Freiberg and colleagues proposed a 2-tier classification system based on the pattern of inflammation along the involved tendon – nodular or diffuse. The nodular group had a local, contained, palpable nodule within the tendon sheath and was found to have a much higher success rate with nonoperative management, 93%, compared with a diffuse inflammation group, 47%. The results between these 2 types of flexor tendon sheath inflammation, however, have not been reproduced in further investigations. As such, the Quinnell system is more frequently used in the clinical and research setting.

| Grade 0 | Pain with flexion, no mechanical symptoms |

| Grade 1 | Uneven motion during flexion/clicking |

| Grade 2 | Locked digit that is actively corrected |

| Grade 3 | Locked digit that is passively corrected |

| Grade 4 | Locked digit, uncorrectable/fixed flexion contracture |

Adult trigger digit

Stenosing flexor tenosynovitis of the hand, commonly known as trigger finger, is a potentially debilitating condition characterized by catching, clicking, or locking of the fingers. The etiology is any pathology between the flexor sheath and the underlying tendons that impedes smooth gliding during flexion. Early epidemiologic studies found a 2.6% lifetime risk of developing trigger finger, with an increased incidence in certain systemic conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and inflammatory arthridities. Women are more affected than men and the thumb is the most commonly involved digit.

The flexor sheath, enveloping the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), is composed of 5 annular pulleys and 3 cruciate pulleys ( Fig. 1 ). In-between the sheath and the underlying tendon is a thin synovial membrane that decreases the friction during gliding. The etiology of trigger finger is chronic repetitive friction between the tendon and the A1 pulley, which imparts a high angular load on the underlying tendon during flexion. In the thumb, the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) enters the tendon sheath at a more acute angle, in contrast to the FDP and FDS tendons, providing a mechanical strength advantage; however, this is likely the reason it has the highest incidence of stenosing flexor tenosynovitis.

Histologic analysis of tissue biopsied from patients with trigger finger shows fibrocartilaginous metaplasia with positive staining for S-100 proteins, usually found in chondrocytes. Similarly, biopsies of tendons diagnosed with trigger finger demonstrate disrupted fibers and hypercellularity, with an increased number of chondrocytes and glycoaminoglycans. No significant amount of inflammatory cell or synoviocyte proliferation was discovered in these studies. These findings are consistent with tendinopathy and suggest that the term, flexor tenosynovitis , is actually a misnomer because there is no evidence of synovial inflammation. The term, flexor tendovaginosis , has been proposed to more accurately reflect the disease process.

Ultrasound examination in patients with symptomatic trigger finger has found that the A1 pulley is significantly thicker and stiffer than normal controls. Three weeks after corticosteroid injection, the thickness and stiffness return to values comparable with healthy A1 pulleys, whereas the cross-sectional area of the FDS and FDP tendons is unchanged. Whether the instigating factor behind the development of digit triggering is a pathologic pulley system or a pathologic tendon remains unclear. By the time clinical symptoms become noticeable, both the tendon and the pulley are likely involved.

The diagnosis of trigger finger is made based on clinical findings. The natural progression of symptoms is painless clicking, followed by painful triggering, and ultimately a flexed, locked digit. With more-advanced disease, patients may report pain radiating retrograde to the forearm. Although a patient may present with advanced symptoms in a single digit, the clinician must astutely examine all other digits because severe symptoms in 1 finger may mask early signs of triggering in other digits. It is prudent to treat all affected digits simultaneously regardless of severity. Further imaging or diagnostic studies are not necessary, unless unusual examination findings warrant ruling out concomitant conditions.

The Quinnell grading system, based on mechanical symptoms, is commonly used to classify trigger finger severity ( Table 1 ). Freiberg and colleagues proposed a 2-tier classification system based on the pattern of inflammation along the involved tendon – nodular or diffuse. The nodular group had a local, contained, palpable nodule within the tendon sheath and was found to have a much higher success rate with nonoperative management, 93%, compared with a diffuse inflammation group, 47%. The results between these 2 types of flexor tendon sheath inflammation, however, have not been reproduced in further investigations. As such, the Quinnell system is more frequently used in the clinical and research setting.

| Grade 0 | Pain with flexion, no mechanical symptoms |

| Grade 1 | Uneven motion during flexion/clicking |

| Grade 2 | Locked digit that is actively corrected |

| Grade 3 | Locked digit that is passively corrected |

| Grade 4 | Locked digit, uncorrectable/fixed flexion contracture |

Nonsurgical treatment

Noninvasive treatment modalities are used for mild or early cases of triggering and in patients who are opposed to injections. Activity modification, especially symptom-provoking activities, should be avoided. Although there is no scientific evidence to support the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), this drug class is commonly recommended to alleviate the local inflammatory response secondary to triggering. Prolonged use, however, may contribute to peptic ulcer disease and kidney failure.

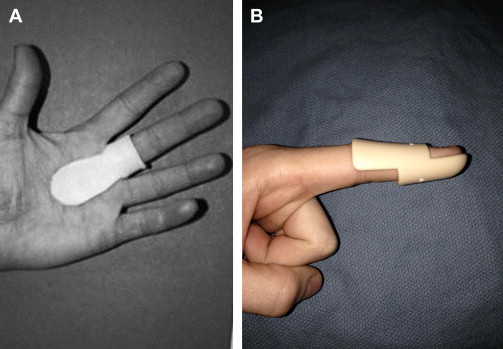

Splinting is a commonly used conservative treatment option with the theoretic concept that limiting tendon gliding allows time for inflammation to resolve ( Fig. 2 ). In a series of 28 patients placed in a metacarpophalangeal (MCP) blocking splint at 10° to 15° of flexion for a 6- to 10-week period, Colbourn and colleagues found that 93% of patients reported improvement in symptoms. Rogers and colleagues achieved 83% success with a distal interphalangeal joint blocking splint, limiting FDP excursion, in a small series of laborers. Tarbhai and colleagues compared these 2 splinting techniques in a randomized trial and found a higher percentage of patients had complete or partial relief of symptoms with the MCP blocking splint (77% vs 43%), although it was subjectively reported as more cumbersome. Immobilization is most effective in mild cases of triggering, with short duration of symptoms, and requires high level of splint compliance.

Local corticosteroids are routinely used as a first-line treatment of trigger finger of all severities. Although local steroid injections are more effective compared with a placebo injection, there is a significant number of patients who fail this modality or develop recurrence. Castellanos and colleagues performed a review of trigger fingers treated with corticosteroid injections with a mean follow-up of 8 years and found a success rate, defined as resolution of symptoms for at least 36 months, of 69%. A more recent review of the literature found that only 57% of patients had relief with corticosteroid injections. Rozental and colleagues found a recurrence of 56% up to 1 year after injections and found that younger age, type 1 diabetes mellitus, involvement of multiple digits, and history of other tendonopathies were associated with a higher rate of treatment failure. Patients with more than 6 months of symptoms are also less likely to have triggering resolution. The type of steroid has not been shown to affect long-term outcomes. Triamcinolone, however, a non—water-soluble medication, has shown more effective in the short term (6 weeks after administration) when prospectively compared with dexamethasone, a water-soluble steroid. Appropriate counseling should be provided to patients because patience may be required to see a beneficial effect from the steroid.

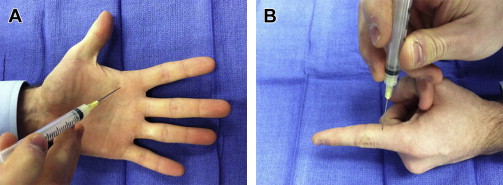

Delivery of the steroid into the tendon sheath is classically thought critical for effectiveness of the treatment. The 2 most commonly used injection techniques are the palmar and midaxial needle trajectories ( Fig. 3 ). The 2 techniques have been found equivalent in delivering medication into the sheath but have not been compared clinically. Kamhim and colleagues demonstrated that injections reach the intrasheath compartment in only 50% of attempts, giving rise to the notion that medication does not need to be in the sheath to be effective. Taras and colleagues compared groups of intrasheath and extrasheath injections and, in contrast to popular belief, found that the extrasheath cohort had better outcomes. Whether to apply the steroid into the tendon sheath or subcutaneously continues to be a topic of debate and a focus for further investigation.