Triceps Tendon Repair and Reconstruction

Bernard F. Morrey

INTRODUCTION

Addressing triceps insufficiency in acute and chronic settings requires several different techniques. All methods used by the author for managing these conditions are presented here.

ACUTE RUPTURE

Indications/Contraindications

Indications

Acute rupture with functional extension weakness or fatigue pain and weakness in a patient who requires extension strength (this includes almost everybody)

Failure to regain extensor strength after several weeks of nonoperative management

Contraindications

Few, if the patient is symptomatic and if the diagnosis has been confirmed

Willingness to perform rehabilitation

Ongoing or generalized enthesopathy and morbidity that will not be addressed by triceps reconstitution

DELAYED RECONSTRUCTION

Indications/Contraindications

Indications

Weakness that has become a major limitation of one’s daily activities

No improvement over the last 3 months after acute injury

Pain rarely a major factor

Inability to extend against gravity after TEA that limits activity

Contraindications

Unclear or unreasonable expectations of the reconstruction

Inability or unwillingness to participate in the postoperative program or to accept the period of postoperative recovery

PREOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Presentation

The most common etiology is after elbow replacement, often seen in body builders or middle-aged males or, conversely, in debilitated states (1,2 and 3). The dominant extremity is involved in only 33% in our experience (4). Approximately 80% have some residual active extension due to the fact that the most common lesion, avulsion of the central attachment, leaves extensor function medially and laterally—the anconeus.

Examination

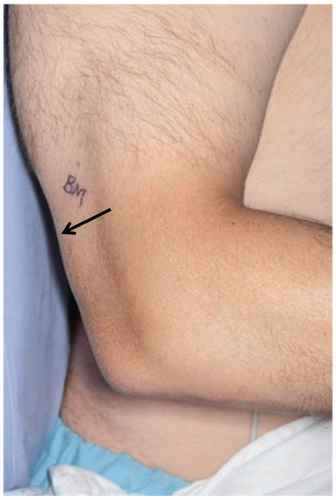

A palpable or visible central defect is present in about 67% (Fig. 23-1). Some weakness is present in all, but complete loss of extension is observed in less than 20% if untreated. Acute avulsion with fleck of bone is seen in only about 15% (4,5). Pain subsides after 10 to 14 days, leaving residual weakness, fatigue, and pain as the major findings. Ability to extend against gravity is occasionally preserved, but not commonly.

IMAGING

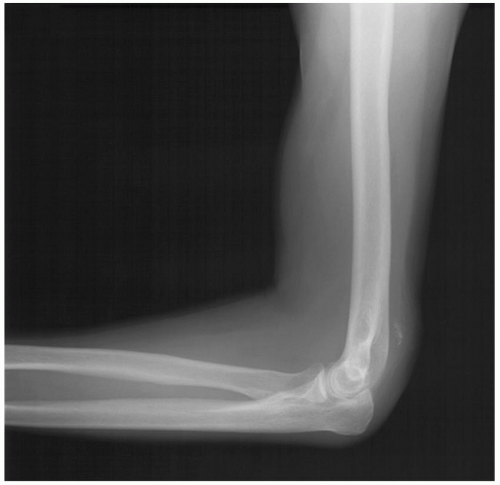

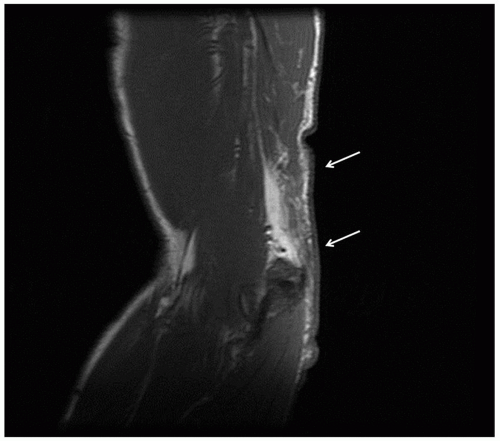

The best evidence is an osseous fleck on the lateral radiograph (Fig. 23-2). An MR examination clearly documents the lesion, but in my practice, it is not required to make the diagnosis. There may be some merit in localizing the disruption, which is usually at the site of attachment of the central slip (6) (Fig. 23-3). The defect is palpable in about two-thirds of cases.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Carefully assess the defect. Palpate the anconeus muscle as the patient extends against resistance. Usually the anconeus expansion is intact, so some extension is possible. The integrity of the anconeus is important to document, as the muscle may be used for rotational reconstruction in chronic cases. Observe the contour of the olecranon process.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE—ACUTE REPAIR

Surgical Repair

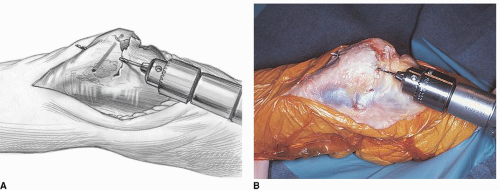

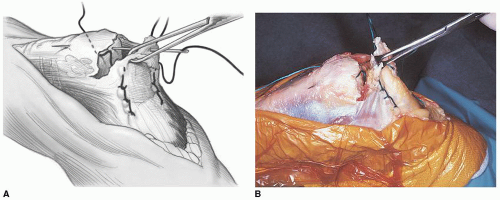

Acute Repair The patient is placed supine on the operating table. The arm is prepped and draped, but the tourniquet is not inflated. A straight posterior skin incision is made and centered just medial to the tip of the olecranon (Fig. 23-4). The dissection carries through the triceps fascia, and the defect is identified. As noted, in most instances, the avulsion is from the central attachment to the olecranon. The precise site of disruption is roughened with a rongeur to enhance healing. Cruciate drill holes are placed in the proximal ulna (Fig. 23-5). A No. 5 Mersilene suture is introduced from distal to proximal. The triceps disruption is mobilized and penetrated laterally by the suture. Three to four throws of a Krackow type of stitch is then placed on each side of the triceps midtendinous locking region. The suture is then brought back through the opposite cruciate hole (Fig. 23-6). This results in a very firm and adequate repair, but a second transverse suture may be placed if there is any question about the security of the attachment. Sutures are tied at the margin of the subcutaneous border of the ulna with the elbow in near full extension (Fig. 23-7).

The arm is elevated, and an anterior splint is applied with the elbow in approximately 15 to 20 degrees of flexion.

FIGURE 23-6 A,B: A Krackow stitch secures the tendon as the suture is being brought back across the olecranon. Note: The tissue is handled with an Allis clamp to avoid crush injury. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree