Treatment of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talar Dome

James W. Stone MD

Although osteochondral lesions can occur over any portion of the talar dome or the tibia, the talar lesions typically occur over the anterolateral or the posteromedial talar dome.

Medial lesions tend to be deeper and cup shaped. Patients tend to present with more chronic symptoms of ankle pain, rather than acute injury. They are found to have an osteochondral lesion on plain radiograph or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the ankle.

Lateral lesions tend to be thinner and more wafer shaped. Patients frequently present with an acute injury and positive radiographic findings.

In the absence of a discrete lesion on plain radiograph, MRI examination is the most appropriate follow-up examination for patients with persistent symptoms despite a period of nonoperative management.

Treatment decisions are based upon the site and size of the lesion, the skeletal maturity of the patient, the quality of the articular cartilage, and the quality of the associated bone fragment.

Surgical approaches include simple excision; excision with curettage; and excision, curettage, and drilling.

Drilling of an intact lesion may be appropriate if arthroscopic evaluation reveals perfect articular cartilage congruity in the absence of a mobile subchondral bone fragment, particularly in the skeletally mature patient.

Internal fixation is usually only appropriate for acute anterolateral lesions with a bone base which is sufficient to support internal fixation with pins or screws.

Most of the lesions requiring surgical treatment are posteromedial in location, have poor quality articular cartilage, a loose bone fragment, necrotic bone beneath the lesion, and are poor candidates for healing with internal fixation. Excision of the loose fragment with treatment of the base by curettage, abrasion, or microfracture has been the most commonly recommended treatment for these lesions.

Newer techniques such as osteochondral autograft, osteochondral allograft, and autologous chondrocyte transplantation are promising; however, long term results are unknown.

The term osteochondritis dissecans was originally applied to lesions of the talar dome of the ankle by Kappis (1) in 1922 referring to abnormalities of the articular cartilage and underlying subchondral bone which can result in fragment separation and loose body formation. Although the term might imply an inflammatory etiology for this lesion, no such association has been noted on pathologic examination of specimens. Indeed, most studies have suggested a traumatic etiology for the majority of these lesions (2,3,4,5). More generic terms such as flake fracture, transchondral fracture, or talar dome fracture have been used in the modern literature on the subject to reflect the fact that the etiology is uncertain in many cases. The most generic term, osteochondral lesion of the talar dome, will be used in this chapter.

Although osteochondral lesions can occur over any portion of the talar dome or the tibia, the talar lesions typically occur over the anterolateral or the posteromedial talar dome. The medial lesions tend to be deeper and cup shaped whereas the lateral lesions tend to be thinner and more wafer shaped (2). The vast majority of lateral lesions are associated with a distinct traumatic episode and patients frequently present with an acute injury and positive radiographic findings. The patients with medial lesions tend to present with more chronic symptoms of ankle pain rather than an acute injury, and are found to have an osteochondral lesion on plain radiograph or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the ankle. The more chronic nature of the medial lesions along with the absence of a definite traumatic association with many medial talar dome lesions supports the possibility that they are either due to low level repetitive trauma or perhaps to another cause such as avascular necrosis, steroid use, embolic event, endocrine abnormality, or hereditary factors (6). In addition, although the lateral lesions are usually unilateral, the medial lesions are found to be bilateral in up to 10% of patients (2).

Most studies have suggested that the lesions are traumatic in nature. They can occur after a single specific injury, or be the result of repetitive microtrauma. The repetitive trauma events may be in the form of recurrent ankle sprains, where joint deformation causes direct impact of the talar dome on the adjacent tibia or talus. This is the theory supported by the early study of Berndt and Harty (3) where a small number of talar dome lesions were created in cadaver ankles by applying inversion or eversion forces combined with ankle dorsi or plantar flexion. The lateral talar dome lesion could be produced with a combination of ankle dorsiflexion and inversion. The medial lesion could be produced when the plantarflexed foot was subjected to an inversion force. Although their numbers were very small (only a total of three lesions were created in a total of 15 ankles), their study suggested that the lateral lesion resulted when the anterolateral talar dome impacted the articular surface of the fibula with the ankle in a dorsiflexed position. In contrast, when the externally rotated ankle was in a plantar flexed position, inversion of the joint resulted in physical contact of the posteromedial talar dome with the tibial articular surface. Stauffer (7) refined the biomechanical explanation of causation of these lesions, suggesting that relatively small tangential or shear forces resulted in bony fracture with the articular cartilage remaining intact, whereas failure of both bone and articular cartilage occurs with application of larger forces.

A patient with an osteochondral lesion of the talar dome will most commonly present with a chief complaint of ankle pain, sometimes poorly localized and nonspecific. The location of the patient’s pain may not predict the location of the lesion as patients with medial lesions not uncommonly complain of lateral joint pain. Although one might expect a loose lesion to cause mechanical symptoms, complaints of locking, catching, or swelling are less common, except when a lateral lesion has caused an acute loose body to be formed. Pain with weight bearing and a sensation of giving way are more common but nonspecific complaints. The patient will usually report a distinct episode of trauma when a lateral lesion is present, but with medial lesions there may be no specific injury or the common historical association of one or more ankle sprains in the past.

Swelling is commonly found in acute injuries, although it may be absent in chronic cases especially with medial lesions. Tenderness localized to the joint line may be noted in the plantar flexed ankle laterally in the case of an anterolateral talar dome lesion and posteromedially in the dorsiflexed ankle in the case of a posteromedial lesion. Either lesion may be associated with clinical evidence of joint laxity, so the examiner should compare the effected joint to the normal joint and check for evidence of anterior or lateral laxity. Because the history and physical examination findings are often nonspecific and the differential diagnosis includes multiple other entities such as tendonitis, instability, impingement lesions, neurological causes such as neuroma or tarsal tunnel syndrome, subtalar symptoms including os trigonum, a careful physical examination must be performed to assess these possibilities.

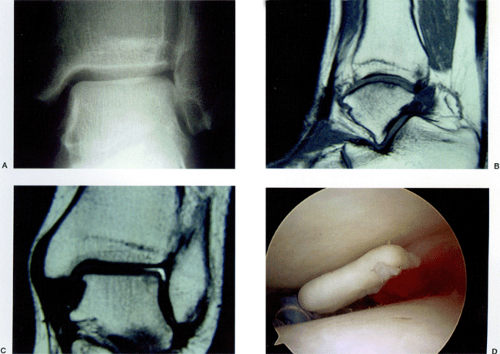

Plain radiographs are indicated in the evaluation of any patient with acute or chronic ankle pain. Routine views include anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and mortise views. In addition, the mortise view may be obtained in plantar flexion to better assess a posteromedial lesion or in dorsiflexion to assess an anterolateral lesion. The staging system proposed by Berndt and Harty (3) as applied by them combined both radiographic and surgical findings, but in the modern literature has been applied only to plain radiographic findings (Table 49-1).

In the absence of a discrete lesion on plain radiograph, MRI examination is the most appropriate follow-up examination for patients with persistent symptoms despite a period of nonoperative management. MRI is sensitive in detecting osteochondral lesions of the talar dome and may also aid in the evaluation of other soft tissue and bony entities on the differential diagnosis. If an osteochondral lesion is noted on plain radiographs, the MRI may be useful in evaluating the lesion itself for articular cartilage congruity, whether there is fluid signal beneath the bony fragment to suggest a loose lesion and to evaluate the degree of edema in the surrounding talus. Because the MRI is very sensitive in

detecting bone edema, it may actually overestimate the size of the lesion. Several classification schemes for MRI evaluation have been suggested (8). They tend to mimic the plain radiographic evaluation suggested by Berndt and Harty (3), but add the evaluation of the cystic component which is present in may of the osteochondral lesions (Table 49-2). The MRI also has the advantage over both plain radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scanning in its ability to detect the true Stage I lesion where the only finding may be edema in the body of the talus without a discrete bony lesion.

detecting bone edema, it may actually overestimate the size of the lesion. Several classification schemes for MRI evaluation have been suggested (8). They tend to mimic the plain radiographic evaluation suggested by Berndt and Harty (3), but add the evaluation of the cystic component which is present in may of the osteochondral lesions (Table 49-2). The MRI also has the advantage over both plain radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scanning in its ability to detect the true Stage I lesion where the only finding may be edema in the body of the talus without a discrete bony lesion.

TABLE 49-1 Berndt and Harty Classification: Osteochondral Lesions of the Talar Dome | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

TABLE 49-2 Anderson et al. MRI Classification: Osteochodral Lesions of the Talar Dome | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

CT is the most precise means of evaluating the bone lesion itself. CT staging again mimics the plain radiographic and MRI evaluations and also incorporates evaluation of the cystic component (9) (Fig 49-1). Primary axial and coronal

thin section CT scanning combined with sagittal reconstructions give the best bony detail.

thin section CT scanning combined with sagittal reconstructions give the best bony detail.

There is no universally accepted treatment algorithm for osteochondral lesions of the talar dome. This lack of consensus stems from several factors, including the absence of controlled, randomized studies comparing various treatment alternatives, lack of studies documenting the natural history of untreated lesions of various stages, the addition over time of new diagnostic modalities such as CT and MRI which have expanded our ability to define the lesions preoperatively, and the addition of arthroscopy to the surgeon’s armamentarium. Treatment decisions are based upon the site of the lesion, the size of the lesion, the skeletal maturity of the patient, the quality of the articular cartilage, and the quality of the associated bone fragment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree