Intra-Articular Lesions

Aaron A. Bare MD

Carlos A. Guanche MD

When a pathologic process alters the function of the homeostatic chemical and mechanical forces within the hip joint, articular cartilage breakdown can occur and joint deterioration may follow.

Disruption of the articular surface dynamics usually responds best to surgical debridement, repair, or removal of the offending lesion or lesions.

Arthroscopy offers a minimally invasive solution compared to traditional open techniques.

Open exposure of the joint remains an option for conditions not amenable to arthroscopic technique, such as fixation of large osteochondral lesions.

Loose bodies within the joint can cause pain and may mimic the snapping hip phenomenon.

A disruption of the acetabular labrum alters the biomechanical properties of the hip. The forces acting on the hip in the setting of a torn labrum often cause pain during sports participation. Patients with labral tears often present with mechanical symptoms, such as buckling, clicking, catching, or locking.

The most commonly reported cause of a traumatic labral tear is an externally applied force to a hyperextended and externally rotated hip. However, a specific inciting event often is not identified, and the patient presents for evaluation after failed attempts to management of groin pulls, muscle strains, or hip contusions.

Femoroacetabular impingement is a structural abnormality of the femoral neck which can lead to chronic hip pain and subsequent acetabular labral degenerative tears. The repetitive microtrauma from the femoral neck abutting against the labrum produces degenerative labral lesions in the anterior-superior quadrant.

Impingement often occurs in extreme ranges of motion. While in flexed position, patients exhibit a decrease in both internal rotation and adduction, often accompanied by pain.

Osteonecrosis can cause severe pain and disability in young patients. It occurs most commonly between the third and fifth decades of life. Osteonecrosis can be the result of trauma that disrupts the blood supply of the femoral head. Nontraumatic risk factors include: corticosteroid use, heavy alcohol consumption, sickle cell disease, Gaucher and Caisson disease, and hypercoaguable states.

Instability of the native hip is much less common than shoulder instability, but can cause a significant amount of disability. The labrum provides a great deal of stability at extremes of motion, particularly flexion. With a torn or absent labrum, a great deal of force is transmitted through the capsule.

Traumatic dislocations of the hip can lead to capsular redundancy and clinical hip laxity.

Hip instability has been recognized in sports with repetitive hip rotation with axial loading, such as golf, figure skating, football, gymnastics, ballet, and baseball. A common injury pattern for athletes is labral degeneration combined with subtle rotational hip instability. This has been successfully treated with labral debridement and thermal capsulorrhaphy.

Rheumatoid arthritis is a common inflammatory arthritis that can affect the hip. Arthroscopic synovectomy has been used as a treatment aimed to improve symptoms and slow progression of the disease.

Patients with underlying chronic conditions, such as osteonecrosis or connective tissue disorders, may benefit from a diagnostic and therapeutic arthroscopy, when mechanical symptoms are present.

Approximately 2.5% of all sports related injuries are located in the hip region, and this figure increases to 5% to 9% of high school athletes (1). Painful hips in the young and middle-aged patients impose a diagnostic challenge. With improved imaging modalities and an increasing capacity to treat intra-articular pathology, more diagnoses and treatments are available than a decade ago. Arthroscopic treatment of intra-articular and extra-articular lesions of the hip continues to expand, with recent advances providing an invaluable diagnostic as well as treatment vehicle for hip pathology. As a result, our awareness of many hip problems has increased. We now have more definitive answers for the active patient without radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease and less commonly must formulate vague diagnoses such as generalized hip sprains, strains, or tendonitis.

The hip joint often functions without problems for 7 or 8 decades under normal physiologic loads, which include loads of up to five times body weight. When a pathologic process alters the function of the homeostatic chemical and mechanical forces within the joint, articular cartilage breakdown can occur and joint deterioration may follow. Unfortunately, a large percentage of patients are not evaluated or diagnosed until the process affecting the joint is established. Once bony changes have occurred, the process of joint deterioration becomes progressive and usually irreversible. While aging defines a large portion of patients with hip degenerative joint disease, younger patients with intra-articular disruptions have acute symptoms and are at risk of developing a chronic disability. Improved imaging modalities and arthroscopic techniques have introduced the ability to identify and treat intra-articular pathology in hopes of preventing the degenerative cascade.

The majority of intra-articular pathology does not respond well to conservative treatment. Disruption of the articular surface dynamics usually responds best to surgical debridement, repair, or removal of the offending lesion or lesions. Treatment of intra-articular lesions can be performed either open or arthroscopically. Arthroscopy, however, offers a minimally invasive solution compared to the traditional open techniques. It spares extensive surgical dissection and violation of the hip capsule. While the range of pathology amenable to arthroscopic treatment in the hip continues to expand, open exposure of the joint remains an option for conditions not amenable to arthroscopic techniques such as fixation of large osteochondral lesions. The goal of surgical treatment of intra-articular lesions is to restore near normal intra-articular anatomy and biomechanical forces. Inferior arthroscopic results, therefore, should not be accepted from inexperienced surgeons.

Burman (2) first introduced arthroscopic surgery of the hip in 1931. While procedures for the shoulder and knee flourished in the 1980s, hip arthroscopy received relatively little attention. Within the last 10 years, a variety of studies have documented the success of treating a wide range of intra-articular pathology of the hip. Current indications for intra-articular hip arthroscopy include removal of loose bodies, treatment of acetabular labral tears, avascular necrosis (AVN), synovial and connective tissue disorders, chondral lesions, and the treatment of impingement.

Loose bodies within the joint can cause pain and may mimic the snapping hip phenomenon. Anterior groin pain, episodes of clicking or locking, buckling, giving way, and persistent pain during activity suggest an intra-articular loose body. McCarthy and Busconi (3) showed that loose bodies within the hip, whether ossified or not, correlated with locking episodes and inguinal pain.

In cases of traumatic injury or dislocation, suspicion should be high for loose bodies to explain hip symptoms. Besides hip trauma, other diseases known to be associated with loose bodies include Perthes disease, osteochondritis dissecans, AVN, synovial chondromatosis, and osteoarthritis. When identified by computed tomography (CT) scanning during closed treatment of an acetabular fracture or a hip dislocation, Keene and Villar (4) advocate early arthroscopic retrieval of traumatic loose bone fragments from the joint to eliminate additional insult to the articular surface.

Radiographs often identify loose bodies, but noncalcified lesions may not appear on standard radiographs. CT scans are highly sensitive for detection of suspected loose bodies and are more sensitive than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (5). Loose bodies may occur as an isolated lesion following trauma or may present with many intra-articular lesions as seen in synovial chondromatosis.

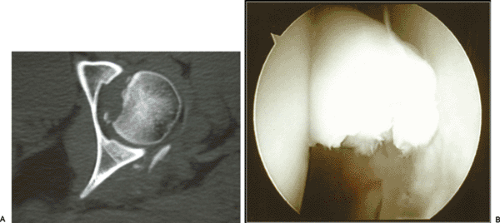

Although arthrotomy remains the gold standard for direct observation and removal of intra-articular and extra-articular objects or loose bodies, the morbidity of an open approach and hip dislocation is significant. Hip arthroscopy offers an excellent method for removal of the lesions. McCarthy and Busconi (3) reported that radiographs did not visualize 67% of loose bodies in the hip. When persistent symptoms of locking or catching are present, further work-up for loose bodies should be performed. A CT scan is the imaging modality of choice to pursue, followed by a diagnostic or therapeutic hip arthroscopy (Fig 27-1). A history of trauma followed by mechanical symptoms suggests either an articular loose body, chondral injury, or a labral injury. While CT scans best evaluate loose bodies, an MRI offers the best imaging modality for labral injures, therefore occasionally both studies are required for the diagnosis.

Osteoarthritic changes in the hip can be caused by intra-articular bone and chondral frag ments or from a step-off at the articular surface. Osteoarthritis has been documented to

occur at a rate of approximately 25% to 55% following all native hip dislocations at a follow-up of 10 years, with simple dislocations having a better prognosis (6). Upadhyay et al. (7) reported osteoarthritic changes at 5 years following traumatic posterior dislocation of the hip. Yamamoto et al. (6) evaluated 11 hips arthroscopically after major hip trauma. In seven cases, small osteochondral or chondral fragments visualized arthroscopically were not seen on radiographs or CT scans. Even though the patient series was small, because over half of the patients had free fragments documented on arthroscopy, there is a broadening indication for diagnostic arthroscopy and lavage following hip trauma.

occur at a rate of approximately 25% to 55% following all native hip dislocations at a follow-up of 10 years, with simple dislocations having a better prognosis (6). Upadhyay et al. (7) reported osteoarthritic changes at 5 years following traumatic posterior dislocation of the hip. Yamamoto et al. (6) evaluated 11 hips arthroscopically after major hip trauma. In seven cases, small osteochondral or chondral fragments visualized arthroscopically were not seen on radiographs or CT scans. Even though the patient series was small, because over half of the patients had free fragments documented on arthroscopy, there is a broadening indication for diagnostic arthroscopy and lavage following hip trauma.

Fig 27-1.A: Axial CT illustrates loose bodies within the hip joint along with a humeral head defect following a posterior hip dislocation. B: Arthroscopy of the joint allows for loose body removal. |

The presence of a loose body within the articulating surfaces of any joint theoretically will result in destruction of the hyaline cartilage, and ultimately result in premature arthritic degeneration. The significance of a symptomatic loose body in the hip should not be understated, and the treatment, arthroscopically or open, should not be delayed. When hip disease or a pathologic condition results in loose body formation, symptomatic improvement can be expected after arthroscopic removal, but the effect on the future of the joint remains dependent on the natural history of the underlying condition. The minimally invasive nature and low morbidity associated with hip arthroscopy make the procedure ideal for establishing an early preventive strategy to treat symptomatic patients with loose bodies in the hip.

The acetabular labrum is a rim of triangular fibrocartilage that attaches to the base of the acetabular rim. It surrounds the perimeter of the acetabulum and is absent inferiorly where the transverse ligament resides. The labrum provides structural resistance to lateral motion of the femoral head within the acetabulum, enhances joint stability, and preserves joint congruity (8). Similar to the meniscus, it also functions to distribute synovial fluid and provides proprioceptive feedback (9).

A disruption of the acetabular labrum alters the biomechanical properties of the joint. The forces acting on the hip in the setting of a torn labrum often cause pain during sports participation in athletes. Altenberg (10) in 1977 was the first to describe tearing of the acetabular labrum as a source of hip pain. Patients with labral tears often present with mechanical symptoms, such as buckling, clicking, catching, or locking. Athletes may present with subtle findings, including dull, activity-induced, positional pain that fails to respond to rest. The most commonly reported cause of a traumatic labral tear is an externally applied force to a hyperextended and externally rotated hip (11). However, a specific inciting event often is not identified and the patient presents for evaluation after failed attempts at conservative management for groin pulls, muscle strains, or hip contusions.

The mechanism of labral tearing can be either traumatic and acute, or chronic and degenerative. Hip impingement chronically loads the anterosuperior labrum and leads to degenerative tears in that region of the acetabulum. The location of labral tears has varied based on different regions. North American series have reported that the vast majority of tears are located anteriorly and acute tears result from sudden pivoting or twisting motions (12). In contrast, in Asian populations, tears are found more frequently posteriorly and are associated with hyperflexion or squatting (11).

Lage et al. (13) have described an arthroscopic classification of labral tears. Labral tears were divided into four groups: radial flap tears, radial fibrillated tears, longitudinal peripheral tears, and mobile tears. Radial flaps were the most common, followed by radial fibrillated, longitudinal peripheral and

mobile tears. They also classified degenerative tears based on location and the extent of the tear. Stage I degenerative tears are localized to one segment of an anatomic region, anterior or posterior. Stage II tears involve an entire anatomic region, and stage III tears are diffuse and involve more than one region. They found that the extent of the degenerative tear correlated to the degree of degenerative changes within the joint. The degree or increasing stage of degenerative labral tears correlated with erosive changes of the acetabulum or femoral head. The articular lesions are most often located adjacent to the labral tear, often at the labrochondral junction.

mobile tears. They also classified degenerative tears based on location and the extent of the tear. Stage I degenerative tears are localized to one segment of an anatomic region, anterior or posterior. Stage II tears involve an entire anatomic region, and stage III tears are diffuse and involve more than one region. They found that the extent of the degenerative tear correlated to the degree of degenerative changes within the joint. The degree or increasing stage of degenerative labral tears correlated with erosive changes of the acetabulum or femoral head. The articular lesions are most often located adjacent to the labral tear, often at the labrochondral junction.

Labral tears secondary to trauma generally are isolated to one quadrant depending on the direction and extent of the trauma. For instance, patients with a known posterior subluxation or dislocations most frequently have posterior labral tears. If a bone fragment is avulsed as a result of a dislocation, the labral injury most often occurs on the capsular or peripheral region of the labrum and may be amenable to an arthroscopic repair (14). Patients with minor trauma often have anterior and more central tears, located in the same region as those for impingement and those seen in athletes.

Idiopathic tears are often seen in the athletic population. Chronic, repetitive loading of the hip can subject the labrum to tensile and compressive forces and lead to tearing (Fig 27-2). Often, no specific recognizable injury is reported. The majority of patients participate in sports requiring repetitive pivoting or twisting, such as football, soccer, basketball, or ballet. It has been theorized that recurrent torsional maneuvers subject the anterior portion of the articular-labral junction to recurrent microtrauma and eventual mechanical attrition (14). McCarthy et al. (14) performed arthroscopic labral debridement on 13 hips in ten competitive athletes with mechanical symptoms stemming from labral tears. All hips had anterior labral tears, with two hips having additional posterior tears. Twelve of thirteen patients had successful results following arthroscopy and returned to competitive activities. Of note, four of the twelve hips had associated chondral lesions requiring debridement. Stated in their conclusion, “hip arthroscopy is the new gold standard for treating the elite athlete with intractable hip pain with mechanical symptoms.”

Fig 27-2. A T1 (A) (arrow) and a T2 (B) (circle) MRI sagittal oblique illustrate a degenerative labral lesion in the anterosuperior quadrant. Arthroscopy (C) reveals the degenerative lesion. |

Radiographs are often unremarkable when evaluating for a labral tear. Specific attention should be given to the superior neck, looking for subtle irregularities in the femoral head-neck offset and decreased neck concavity compared to the contralateral side, which would suggest impingement.

Contrast enhanced MRI arthrography is more sensitive than standard MRI at detecting intra-articular lesions of the hip (15). Czerny et al. (15) compared conventional MRI with MR arthrography in the diagnosis of labral lesions. They reported a sensitivity and accuracy of 80% and 65% for conventional MRI compared with 95% and 88% with MR arthrography. However, hip MR arthrograms are not without frequent misinterpretation. Byrd and Jones (16) found an 8% false-negative rate and a 20% false-positive interpretation of MR arthrograms for all types of intra-articular pathology of the hip. While MR arthrograms offer a diagnostic advantage over conventional MRI for labral tears and other intra-articular pathology, their reported false-positive rate dictates cautious interpretation. Newer MR imaging modalities such as fast spin echo have improved the imaging capability of articular cartilage and may obviate the need for intra-articular gadolinium in the future (5).

Contrast enhanced MRI arthrography is more sensitive than standard MRI at detecting intra-articular lesions of the hip (15). Czerny et al. (15) compared conventional MRI with MR arthrography in the diagnosis of labral lesions. They reported a sensitivity and accuracy of 80% and 65% for conventional MRI compared with 95% and 88% with MR arthrography. However, hip MR arthrograms are not without frequent misinterpretation. Byrd and Jones (16) found an 8% false-negative rate and a 20% false-positive interpretation of MR arthrograms for all types of intra-articular pathology of the hip. While MR arthrograms offer a diagnostic advantage over conventional MRI for labral tears and other intra-articular pathology, their reported false-positive rate dictates cautious interpretation. Newer MR imaging modalities such as fast spin echo have improved the imaging capability of articular cartilage and may obviate the need for intra-articular gadolinium in the future (5).

Not only should imaging studies be interpreted with caution but physical exam findings are often inconsistent. Farjo et al. (17) did not find specific exam findings to correlate with labral injuries. However, Fitzgerald (18) found the Thomas test correlated with surgical pathology. Bilateral hip flexion, followed by abduction and extension of the involved hip with a palpable or audible click along with pain defines a positive Thomas test. Another available test, similar to the Thomas test, is the McCarthy test: Both hips are flexed; the affected hip is then extended, first in external rotation, then in internal rotation. Hip extension in internal rotation will stress the anterior labrum, and extension with external rotation will elicit posterior pathology.

MRI may confirm the diagnosis, but the decision to proceed with operative intervention should be heavily weighted on refractory, mechanical symptoms. The majority of labral tears are treated by debridement; however some tears are amenable to arthroscopic repair. Petersen et al. (19) studied blood supply to the labrum and found blood vessels enter the labrum from the adjacent joint capsule. Vascularity was detected in the peripheral one-third of the labrum and the inner two-thirds of the labrum are avascular, similar to the meniscus. Thus, peripheral tears have healing potential and repairs should be considered (Fig 27-3). Peripheral tears, however, are a rarity. McCarthy et al. (14) reported 436 consecutive hip arthroscopies performed over 6 years and treated 261 labral tears, all of which were located at the articular junction.

For articular or centrally based as well as degenerative tears, the goal of arthroscopic debridement is to relieve pain and mechanical symptoms while preserving healthy, intact portions of the labrum. Kelly et al. (20) reviewed the results of more the 500 acetabular debridements and found nearly 90% good to excellent results at short-term follow-up. Farjo et al. (17) reported good to excellent results for debrided acetabular tears without concomitant arthritis and only 21% good or excellent results for patients with articular cartilage damage discovered intra-operative. McCarthy et al. (14) published good to excellent results for debridement of labral lesions without articular cartilage involvement and less than 40% good to excellent results for patients with associated articular cartilage lesions. Therefore, patient outcomes are significantly more favorable after operative treatment for labral lesions without concomitant degenerative joint disease.

Whether acetabular labral tears lead to degenerative joint disease has yet to be determined. McCarthy et al. (21) reported that labral tears might contribute to the progression of degenerative disease of the hip. They found an association between the progression of labral lesions and the progression of anterior acetabular articular cartilage lesions. The frequency and severity of acetabular articular degeneration was statistically significantly higher in patients with labral lesions than those without. This association, however, does not offer a definitive causal relationship. Currently, arthroscopic findings have supported the theory that labral disruptions and degenerative joint disease are linked as part of a continuum. Labral tears, idiopathic, traumatic, or degenerative in nature, can progress to articular cartilage delamination adjacent to the labral lesions and slowly progress to more global labral and articular destruction. Therefore, treatment of patients with mechanical symptoms with underlying labral pathology will not only alleviate symptoms but may prevent the development of degenerative cartilage lesions.

Femoral neck impingement against the acetabular labrum or femoroacetabular impingement has been described as a structural abnormality of the femoral neck which can lead to chronic hip pain and subsequent acetabular labral degenerative tears. The repetitive microtrauma from the femoral neck abutting against the labrum produces degenerative labral lesions in the anterior-superior quadrant of the labrum. This mechanical impingement is believed to originate from either

a “pistol grip” deformity of the femoral neck or a retroverted acetabulum.

a “pistol grip” deformity of the femoral neck or a retroverted acetabulum.

A “pistol grip” femoral neck is a neck with a decreased femoral head-neck offset on the superior or anterolateral neck. A decreased offset of the anterolateral head-neck junction causes a reduction in joint clearance and can lead to repetitive contact between the femoral neck and the acetabular rim. Several recent studies (21,22,23) have shown an association between labral tears and osteoarthritis as well as labral tears in the setting of impingement. Therefore, a specific subset of patients may be predisposed to the development of labral lesions and osteoarthritis based on an altered morphology of the anterolateral femoral neck. Evidence to support this theory remains circumstantial, but treatment of symptoms by attempting to correct the structural abnormality often allows patients to return to normal activities.

Impingement often occurs in extreme ranges of motion. Abutment from the superior neck occurs in flexion, often with a variable degree of adduction and internal rotation. The repetitive trauma not only damages the labrum, but can create adjacent chondral injuries. Beck et al. (24) noted all patients treated operatively for impingement had labral lesions in the anterosuperior quadrant and that labral and cartilage lesions correlated with an absent anterolateral offset of the head-neck junction.

The etiology of the abnormal neck morphology is not completely understood. The pistol grip deformity has been attributed as a form of mild or subclinical slipped capital epiphysis (25). Nonspherical heads with a wide neck have also been described as the result of a growth disturbance of the proximal femur (26). Recently, Siebenrock et al. (27) reported an increase in the lateral epiphyseal extension in patients with decreased head-neck offset and a larger extension of the epiphysis onto the neck in the anterosuperior quadrant. They showed that an increased physeal extension into the cranial hemisphere of the femoral head neck is associated with a decreased head-neck offset. This suggests that a growth abnormality of the capital physis is a possible cause of the development of a decreased head-neck offset in patients with anterolateral impingement. Overall, several theories exist to explain the femoroacetabular impingement phenomenon but the inciting event has not been agreed upon.

Currently, evidence suggests that femoroacetabular impingement may play a role in the cascade of hip osteoarthritis in some patients: those with structural proximal femoral head-neck abnormalities (21,22,23,24,28). This entity usually appears in younger and more physically active adults and can be physically debilitating. Subsequent labral and chondral lesions have been linked to repetitive microtrauma caused by the pistol grip deformity of the femoral neck (29). The operative management of these lesions offers two benefits. First, for symptomatic patients: who fail conservative treatment, the removal of the structural abnormality will provide significant pain relief. Because labral and chondral lesions are seen more frequently in early osteoarthritic hips, early recognition and treatment of this entity may curb or halt the unfortunate progression to osteoarthritis in these younger patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree