Treatment of Medial Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injuries in Athletes

Christopher S. Ahmad

Neal S. ElAttrache

INTRODUCTION

Frank W. Jobe developed the original MCL reconstruction and described the technique with initial results in 1986 (1). The original technique transected and reflected the flexor-pronator mass, transposed the ulnar nerve to a submuscular position, and created humeral tunnels that penetrated the posterior humeral cortex. Excellent exposure was achieved at the expense of morbidity to the flexor-pronator mass and handling the ulnar nerve. Since that initial report, modifications in the surgical technique have been made to ease technical demands and decrease soft tissue morbidity. A muscle-splitting approach has been developed to safely avoid detachment of the flexor-pronator mass with or without subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve. Modifications in bone tunnel creation have also been made, which direct the tunnels anterior on the humeral epicondyle to avoid risk of ulnar nerve injury while still allowing figure-of-eight graft passage (2). Further changes in bone tunnel configuration have reduced the total number of large tunnels and facilitate easier graft tensioning (3,4). Results have shown that these modified techniques have proven effective in returning high-level athletes back to throwing (5,6,7 and 8). In addition to advancements in surgical technique, the pathophysiology and diagnosis of MCL injuries have improved. This chapter describes MCL pathophysiology, patient evaluation, and surgical indications and details two popular surgical techniques.

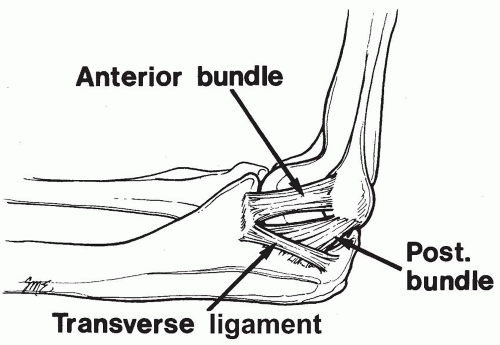

The anterior bundle of the MCL is the strongest component of the medial collateral ligament complex and the primary restraint and stabilizer to valgus stress (9) (Fig. 27-1). The anterior bundle is functionally composed of anterior and posterior bands that provide a reciprocal function in resisting valgus stress through the range of flexion-extension motion (10). Valgus stress is generated at the elbow during throwing maneuvers in baseball, softball, football, tennis serving, and volleyball spiking. The extreme valgus torque created during the acceleration phase of throwing, estimated as high as 64 N-m, exceeds the known ultimate tensile strength of cadaveric MCL specimens (33 N-m). Therefore, dynamic valgus stability also plays an important role, with the flexor carpi ulnaris as the primary and the flexor digitorum superficialis as a secondary dynamic stabilizer to valgus force (11). These muscles and others of the flexor-pronator group are enhanced in nonoperative programs or in postoperative rehabilitation. Morbidity to these muscles should be minimized during MCL reconstruction.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

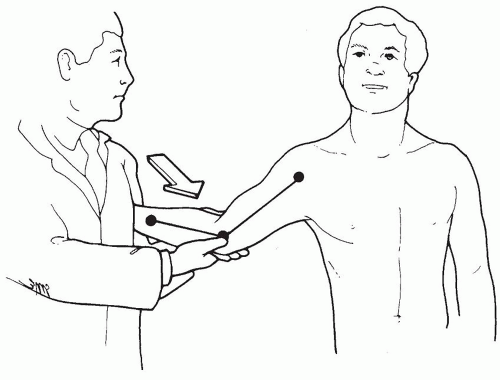

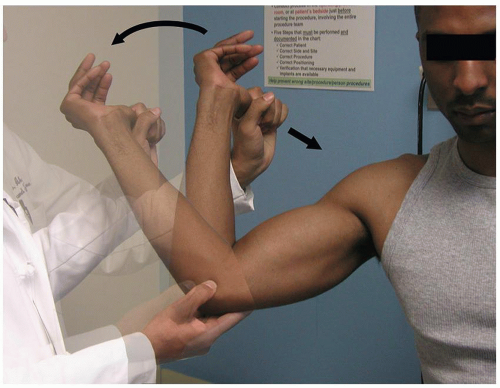

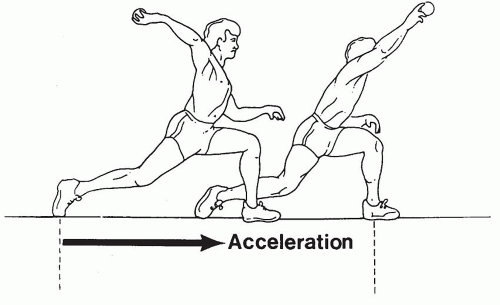

MCL injury diagnosis is established from clinical features and supporting imaging studies. Patients report medial elbow pain during the acceleration phase of throwing (Fig. 27-2). Chronic injuries present gradually and often with pain occurring only when throwing greater than 50% to 75% of maximal effort. Patients experience difficulty warming up, decreased velocity, and problems with pitching accuracy. Acute injuries also occur and may present suddenly with a pop, sharp pain, and inability to continue throwing. Physical examination indicating MCL injury includes point tenderness directly over the MCL or toward its insertion sites. Valgus instability is assessed with the elbow flexed between 20 and 30 degrees to unlock the olecranon from its fossa (Fig. 27-3). The examiner applies a valgus stress and assesses for medial ulnohumeral joint opening or the elicitation of pain. The moving valgus stress test is most sensitive and specific for MCL pathology and is performed by the examiner applying valgus torque while the elbow is then flexed and extended (12) (Fig. 27-4). The test is considered positive if elbow pain is reproduced at the MCL and the pain is maximum between 70 and 120 degrees of elbow flexion.

FIGURE 27-2 Arm and elbow position during acceleration phase of throwing producing high valgus force. |

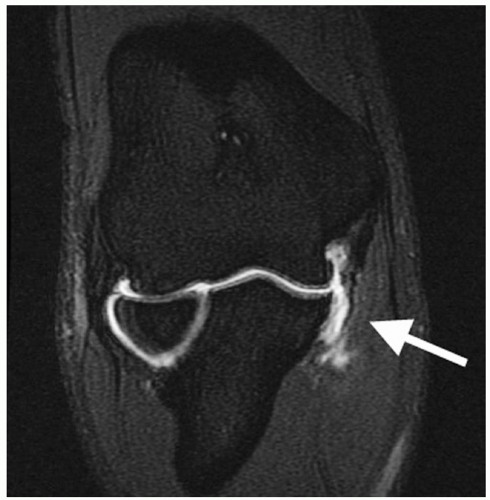

Anterior-posterior, lateral, and axillary views of the elbow are assessed for joint space narrowing, osteophytes, loose bodies, and calcification within the MCL. Valgus stress radiographs may be used to measure medial joint line opening, with opening greater than 3 mm compared to a nonstress view x-ray indicating valgus instability (Fig. 27-5). Conventional magnetic resonance imaging is capable of identifying thickening within the ligament from chronic injury or more obvious full-thickness tears, but MR arthrography improves the diagnosis of partial undersurface tears and is often the preferred imaging technique (Fig. 27-6).

Indications for surgery require consideration of the patient’s athletic demands, expectations, and MCL pathology. Nonthrowing athletes and low-demand recreational athletes are generally treated successfully with nonoperative management. Higher-demand athletes who have injury features with healing capacity are indicated for a trial of nonoperative treatment. These features include absence of chronic changes to the ligament, partial tears, and tears localized to the proximal insertion. Patient characteristics such as young age, modifiable weaknesses in their kinetic chain, and ability to improve throwing mechanics may also be favorable for nonoperative treatment. Seasonal timing that allows for a trial of nonoperative treatment without compromising future participation in an upcoming season also supports a trial of nonoperative treatment. Patients willing to change their sport or their position to decrease throwing demands may also do well with nonoperative treatment. Coexisting

ulnohumeral or radiocapitellar arthritis, flexor-pronator tears, bone deficiency at the sublime tubercle, prior elbow surgery, high school athletes, and failure of prior ligament reconstruction are relative negative factors for surgical success, which may factor into surgical decision making. Patient education is also essential for younger throwing athletes with unrealistic expectations of surgical treatment regarding the risks, benefits, indications, and recovery associated with MCL reconstruction surgery.

ulnohumeral or radiocapitellar arthritis, flexor-pronator tears, bone deficiency at the sublime tubercle, prior elbow surgery, high school athletes, and failure of prior ligament reconstruction are relative negative factors for surgical success, which may factor into surgical decision making. Patient education is also essential for younger throwing athletes with unrealistic expectations of surgical treatment regarding the risks, benefits, indications, and recovery associated with MCL reconstruction surgery.

NONOPERATIVE TREATMENT

Nonoperative treatment typically includes a 6-week period of rest from throwing and early use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cryotherapy. During this time, the elbow is protected with avoidance of valgus stress and flexor-pronator strengthening. Focused effort is made to correct abnormalities in leg and core strength and flexibility, scapular mechanics, rotator cuff and periscapular muscle strengthening, and glenohumeral range of motion restoration. When physical exam normalizes, a supervised progressive throwing program with optimization of throwing mechanics is initiated.

Patients who wish to continue competitive throwing, have failed nonoperative treatment, have an accurate diagnosis of MCL injury, and are willing to participate in the postsurgical rehabilitation are indicated for surgical reconstruction.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Graft Choices

The presence of the palmaris longus tendon should be assessed prior to surgery. The patient opposes the thumb and small finger while resisting wrist flexion to demonstrate a visible and palpable tendon ulnar to the flexor carpi radialis tendon. The palmaris longus is absent bilaterally in approximately 16% of patients and absent unilaterally in approximately 22%. When the palmaris is absent, our graft preference is the ipsilateral gracilis due to its predictable large size and ease of harvest. In addition, the large gracilis is often chosen in cases with significant soft tissue deficiency or bone deficiency making a larger graft preferable. Such deficiency may occur when large ossifications are removed from the injured native ligament.

Ulnar Nerve

Ulnar nerve symptoms are present in as much as 40% of patients with MCL insufficiency (13). Ulnar neuropathy may be secondary to repetitive traction forces from throwing, nerve subluxation, or compression at the cubital tunnel. Percussion along the nerve may elicit a Tinel sign. A positive elbow flexion compression test elicits tingling radiating toward the small finger or pain at the elbow or medial forearm when manual pressure is directly applied over the ulnar nerve between the posteromedial olecranon and the medial humeral epicondyle as the elbow is maximally flexed. Atrophy of the interossei or hypothenar eminence should be assessed but is uncommon. Ulnar nerve subluxation has been identified in 37% of normal elbows and can be determined by placing a finger at the posteromedial aspect of the medial humeral epicondyle of the patient’s actively flexed elbow with the forearm in supination and then having the patient actively extend the elbow. The nerve is noted to “dislocate” if trapped anterior to the examiner’s finger, to “perch” if beneath the finger, or to be stable if not palpable in the groove (14). We reserve ulnar nerve transposition for patients with ulnar neuritis that involves compromised motor function or ulnar neuritis combined with ulnar nerve subluxation.

Arthroscopy

Routine arthroscopic evaluation of the elbow joint prior to MCL reconstruction has been advocated by some, but we recommend arthroscopy when specifically indicated (4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree