Treatment of Anterior Femoroacetabular Impingement through Mini-Open Anterior Approach

Diana Bitar

Javad Parvizi

DEFINITION

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a mechanical hip disorder defined as abnormal abutment between the femoral head or the femoral head-neck junction and the acetabulum. It was initially described as a distinct physiologic entity by Myers et al,28 who noted abnormal contact between the femoral neck and the acetabular rim in a cohort of patients undergoing periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) to correct hip dysplasia.

One of the earlier descriptions of this condition was by Smith-Petersen35 in 1936, when a case of malum coxae senilis was described. The case in that original article resembled what we now describe as FAI. Another description of this condition came in 1970s when the term pistol grip deformity was introduced. The latter was a description of aberrant morphologic features of the femoral head and neck on anteroposterior (AP) radiographs of patients with early idiopathic hip osteoarthritis (OA).24

FAI can be anterior or posterior, with anterior abnormalities being more frequent. The estimated prevalence of FAI in the general population is 10% to 15%38 and is increasingly being recognized as a cause of hip pain in young, active individuals. Repetitive anterolateral impingement produces acetabular articular cartilage delamination, labral disease, and eventually secondary OA. Establishment of a correlation between clinical picture, physical findings, suggestive radiographic structural abnormalities, and positive magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) is crucial for diagnosis and appropriate treatment of this condition.

ANATOMY

Establishing an accurate diagnosis and selecting the optimal surgical treatment strategy relies on a thorough understanding of the pathoanatomy of hip impingement disorders.

Two different structural impingement types have been described:

Femoral-based abnormality (ie, cam impingement) is more common in the young, athletic male16 (M:F ratio = 14:1).38 Cam is a term applied to an eccentric prominence in a rotating mechanism which converts rotary motion into linear motion.26

It is important to note that most FAI cases are likely to be a combination of cam and pincer impingement. In this state, both the proximal femur and the acetabulum present with distorted structural characteristics. Isolated cam or pincer deformities are rare; in 86% of cases, a combined deformity is present.38 In one study of 149 hips with FAI lesions, only 26 hips presented with an isolated cam lesion and 16 hips presented with an isolated pincer lesion.1

Cam-type impingement syndrome can be primary (reduced femoral head-neck offset or an aspherical femoral head) with abnormal physeal development or secondary to previous pathologies (eg, slipped capital femoral epiphysis [SCFE], Perthes abnormalities, developmental dysplasia of the hip [DDH], or as a result of a prior trauma to the proximal femur and/or acetabulum).

Morphologically, cam lesions can result from an osseous bump or from angular deformities of the proximal femur (eg, femoral retrotorsion or coxa vara). The osseous bump location further divides cam lesions into lateral-based prominence (pistol grip) or anterosuperior-based prominence, which is only detected on lateral radiographic views of the hip. Cam impingement owing to femoral angular deformities is uncommon.

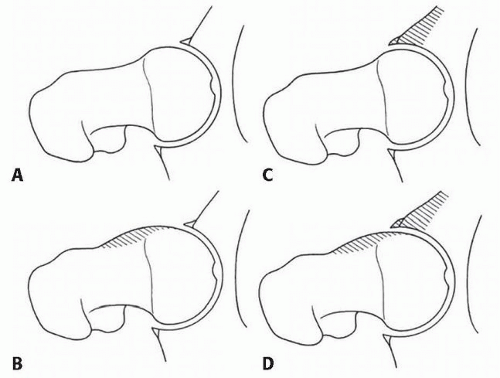

Pincer-type impingement syndrome consists of an overcoverage abnormality, which can be focal or global. Focal overcoverage can be anterior (acetabular retroversion with or without a deficient posterior wall) or posterior (prominent

posterior wall). Global overcoverage consists of concentric deepening of the acetabulum (acetabular dome breaching the pelvic brim) which presents as coxa profunda or protrusio acetabuli, with the latter being the most severe form.

PATHOGENESIS

If left untreated, the process of FAI is likely to lead to hip joint degeneration.13, 23, 39 Mechanical impingement is most noticeable with hip flexion alone or hip flexion combined with internal rotation.

In pincer impingement, a linear contact occurs between the acetabular overcovering rim with a labrum, which acts like a bumper.1 The head-neck junction, with the maximal impact force tangential to the joint surface,38 leads to a full tear of the labrum, which is the first structure to fail in this situation. Sustained mechanical abutment results in degeneration of the labrum with intrasubstance ganglion formation; ossification of the injured labrum leads to further deepening of the acetabulum and worsening of the overcoverage.24

In cam impingement, a jamming of the aspherical head portion (shear stress) into the acetabulum occurs, with the maximal impact force perpendicular to the joint surface, leading to an undersurface tear of the labrum fibrocartilaginous separation,38 which more accurately should be called separation of the acetabular cartilage from the labrum.1

Based on this pathophysiology, the typical location of femoral cartilage damage is circumferential in pincer impingement with contrecoup lesion and is localized between 11 o’clock and 3 o’clock positions in cam impingement.38 A contrecoup lesion is acetabular cartilaginous damage in the opposite part of the femoroacetabular abutment. It is seen in one-third of all cases of pincer impingement and is associated with slight joint subluxation.38 Therefore, the cartilaginous lesions are more benign in pincer impingement than those seen in cam impingement with an average depth of 4 mm in the former and 11 mm in the latter.1, 38

ETIOLOGY

Genetics

Numerous studies conducted on family members, especially sets of twins, have demonstrated a genetic component to OA, which is mostly seen in Caucasians. Furthermore, it has been shown that genetic factors are largely responsible for variations in hip and acetabular morphology and cartilage thickness.26

Based on one genetic study, cam deformity tends to be more prevalent in the family members of affected patients than pincer deformity. There is a relative risk of 2.8 and 2, respectively, that a sibling will have the same abnormal anatomy. Likewise, a positive family history increases the risk of bilateralism of the deformity.18

Geographical Variation

FAI is more prevalent in the Western world where the majority of hip OA, previously labeled primary OA, is currently considered to be the consequence of abnormal hip joint anatomy.

In contrast, in a retrospective study of 946 primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) conducted in Japan, Takeyama et al37 identified FAI as an underlying pathology in only six hips.

Underlying Hip Pathologies

In some cases, FAI is secondary to childhood hip disorders such as SCFE, DDH, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or femoral neck fracture complicated by malunion.

In one study that followed patients for 15 years, those formerly treated for SCFE subsequently displayed signs of FAI.18

As reported by Eijer et al,9 previous femoral neck fractures may result in secondary FAI, specially if the reduction is not completely anatomic.

Snow et al36 reported four cases of anterior cam impingement which occurred after an asymptomatic period following reossification of the femoral head in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.

NATURAL HISTORY

Because FAI is a newly identified condition, the natural history of its development has not been clearly defined in the literature. However, there is an association between morphologic deformities and secondary OA of the hip.

Not all patients with FAI will progress to end-stage disease that requires intervention. It is estimated that one-third of patients with mild OA in the presence of FAI will take more than 10 years to develop end-stage OA, if at all.26

Symptomatic impingement disorders most likely progress to secondary OA, making surgical treatment a rational option.

Close observation and follow-up or prompt and timely conservative surgical treatment should be tailored to each case, taking into consideration clinical presentation, radiographic findings, family history, and especially, the rate of disease progression. Clinicians should be aware that delay of surgical correction may lead to chondral damage and disease progression to a stage where joint preservation procedures may be of little benefit.26

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

History

FAI usually affects active young adults and begins with slow onset of activity-related anterior inguinal (groin) pain that is often preceded by a minor traumatic event.24

Associated lateral (trochanteric) and posterior hip (gluteal) pain is common but the pain is most commonly felt in the groin (83% of cases).26 The pain is often manifested after sitting for a prolonged period.24

In the early stages of the disease, the pain or aching is intermittent and could be aggravated by excessive physical demands on the hip, such as prolonged walking or high-demand athletic activities, including running, cutting, pivoting, and repetitive hip flexion.

Labral disease or unstable articular cartilage flaps3 may cause mechanical symptoms of locking and catching. Anterior FAI is almost always associated with labral tears,5 which are rarely isolated and most likely indicate underlying bony pathologies. Acetabular labral tears should be considered in active patients with a history of groin pain that is exacerbated by activity without radiologic evidence or other hip pathology.3

Stiffness is common, with reductions in the range of hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation in particular,26 whereas overall hip function is almost unaffected.24

After inquiring about the overall performance of the patient (including age, activity level, and comorbidities), a detailed hip-focused history should be conducted to determine any trauma, childhood hip disease, previous surgeries and treatments as well as the impact of hip pain on quality of life.

Physical Examination

After assessment of overall health and body habitus, the hip clinical examination should be done with great care because it provides the most reliable diagnostic information. Physical findings will dictate further tests and necessary management.

Observation of sitting posture, gait, palpation of the hip, abductor strength testing, careful hip range-of-motion (ROM) assessment, and specific provocative tests should be performed.

Anterior FAI commonly provokes discomfort/pain in an upright sitting position, which involves hip flexion greater than 90 degrees.

The gait pattern over short distances and abductor strength are usually normal in the early stages of the disease. A limp, secondary to mild abductor weakness, and positive Trendelenburg test may develop as labral disease and joint degeneration progress.

Hip ROM testing should be performed carefully with stabilization of the pelvis to accurately define motion end points. Passive flexion is often limited to approximately 90 degrees and reduced compared with the contralateral hip. Internal rotation may be severely restricted to just a few degrees. Hip discomfort is often reproduced at the end points of passive motion.

Surgical scars from any previous procedures are inspected to aid in planning of any subsequent surgery. When in doubt, infection should be ruled out.

The anterior impingement test and Patrick test are sensitive maneuvers to detect intrinsic hip disease and usually reproduce hip symptoms in patients with anterior FAI.

The anterior impingement test, also known as the flexion, adduction, and internal rotation test, is performed by flexing the patient’s hip to 90 degrees, adducting and internally rotating it simultaneously.

Patrick test, which is also known as the flexion, abduction, and external rotation test, is performed by crossing the examined limb on the other in a figure-of-four (the ipsilateral heel resting on the contralateral knee) and by applying downward pressure to the knee. If pain is elicited on the ipsilateral side anteriorly, it is suggestive of a hip joint disorder on the same side. If pain is elicited on the contralateral side posteriorly around the sacroiliac joint, it is suggestive of pain caused by dysfunction in that joint.

Moreover, the distance from the ipsilateral knee to the bed should be noted. The test is positive if this distance is greater than the corresponding measurement on the opposite side, if the contralateral hip is considered normal.26

For posterior FAI, an impingement test (performed in the prone position) is considered positive if forced external rotation in full extension is reproducibly painful. Posterior impingement results from focal acetabular overcoverage (pincer); it is manifested radiographically by a posterior wall sign where the too prominent posterior acetabular wall runs lateral to the femoral head center (normally, the posterior rim runs approximately through the femoral head center).38

A posterior impingement test can also be positive in anterior FAI when the disease progresses and posteroinferior traction osteophytes develop, producing clinical symptoms of posterior impingement in extension.

The Drehman sign is positive if hip flexion produces unavoidable passive external rotation of the hip.38

Logroll test is also a useful provocative test in patients with FAI. With the patient in supine position and with the hip and knee in full extension, the foot on the affected extremity is externally rotated. Positive sign is present if this maneuver results in pain in the anterior hip of the rotated extremity.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Investigation of FAI requires a combination of roentgenographic examination and more sophisticated cross-sectional studies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/MRA and sometimes a computed tomography (CT) scan.

Roentgenography

Is the first-line investigation and ideally may include five views: a supine AP view of the pelvis, an axial cross-table lateral view (surgical profile of Arcelin and Danelius-Miller view), a frog-leg lateral view, a false profile (Lequesne view), and a Dunn-Rippstein view in 45 or 90 degrees of flexion.4, 27, 31

The AP and axial cross-table views are crucial and should be taken with the legs in 15 degrees of internal rotation to adjust for femoral antetorsion and fully expose the femoral neck length.

Obtaining an AP view in the supine position allows for a direct comparison with intraoperative and immediate postoperative roentgenograms.38 Standing AP views are important to accurately evaluate and follow joint space narrowing and to apply coxometric measurements.

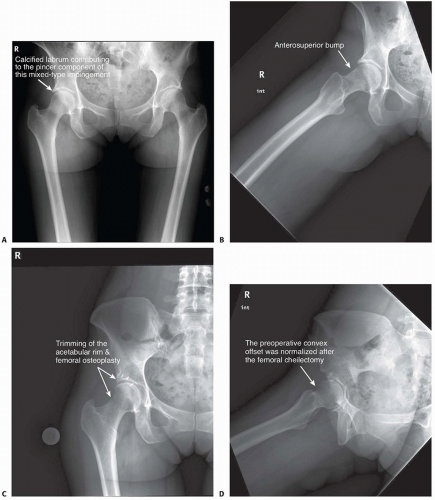

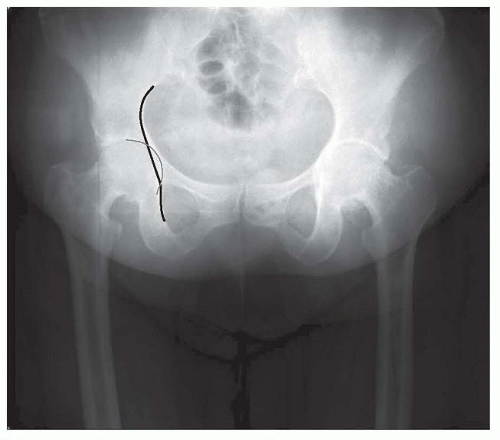

The AP view of the pelvis mainly detects pincer lesions and laterally based cam lesions (pistol grip). Anterosuperior cam lesion can be missed on AP views and should be investigated on at least one, if not all, of the three lateral views (FIG 2).

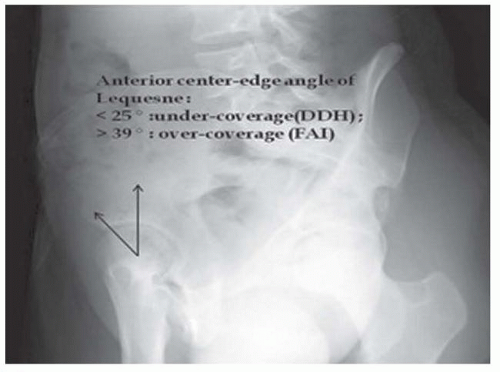

Lequesne view (false profile) is not used for diagnosing FAI because it does not show the relationship between the anterior and posterior acetabular walls. However, it is more likely used for the diagnosis of early joint degeneration in the posteroinferior part of the acetabulum, which is a relative contraindication for joint-preserving surgery.38 The Lequesne view should be included in a thorough radiologic evaluation to exclude associated mild hip dysplasia because it highlights anterior femoral head coverage (anterior centeredge angle of Lequesne) (FIG 3). Attention should be paid to radiographs where the pelvic tilt, rotation, and inclination are seen. X-ray beam centralization should be taken into consideration for correct interpretation of the radiologic hip parameters. The film-focus distance is different for each view: It should be 120 cm in AP and cross-table views but 102 cm in Dunn, frog-leg, and Lequesne views.38

AP view of the pelvis can identify the following:

Lateral cam lesion, which is a pistol grip deformity that has a prominent, convex head-neck junction with reduced head-neck offset26 and an aspherical femoral head (alpha angle measurement)

Acetabular depth, where the acetabular fossa location is noted relative to the Kohler line to look for general acetabular overcoverage. Normally, the fossa is lateral to the Kohler line; coxa profunda is noted when the fossa is medial to this line and protrusio acetabuli when the medial aspect of the

femoral head is medial to this line. Acetabular version: look for the following:

The crossover sign or figure-of-eight sign (first described by Reynolds)26 in anterior acetabular overcoverage (ie, acetabular retroversion)

The prominent wall sign in posterior acetabular overcoverage. Normally, the posterior wall passes approximately through the femoral head center.

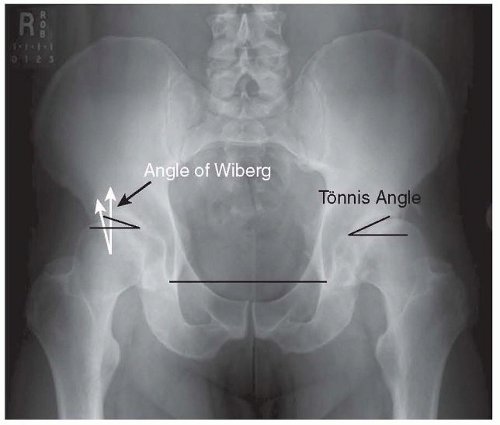

Often, with so-called acetabular retroversion, the ischial spine is abnormally prominent into the true pelvis medially.38 Acetabular inclination is quantified by the Tönnis angle (acetabular index and acetabular roof angle), which is normally 10 degrees or slightly less.

Other coxometric measurements noted on the AP view that quantify acetabular depth include the following:

The lateral center-edge (LCE) of Wiberg: normally varies between 25 and 39 degrees38

The femoral head extrusion index, where the uncovered horizontal portion of the femoral head is quantified, should not exceed 20% to 25%.

The lateral views are examined to assess the following (FIG 6):

Femoral head sphericity: either by gross visual inspection or using the Mose template. Asphericity can be quantified by measuring the alpha angle of Nötzli (abnormal if >50 degrees in women and >68 degrees in men38). However, this angle measurement is subject to poor intraobserver reliability, with 30% of reliability based on an MRI study.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree