Chapter 30 Treatment by Arthroscopy

Introduction

However, the management of elbow stiffness arthroscopically does demand complete confidence and skill in arthroscopic elbow surgery. The stiff joint has a poor capsular compliance and is more difficult to access.1 All standard and often many accessory portals are required to deal with all the restrictive lesions. Additional ‘technical tricks’ may be required to access and treat these lesions. Normal anatomy may be distorted by deformity and/or previous surgery. Nonetheless, once mastered the arthroscopic treatment of stiff elbows can be a rewarding and beneficial procedure for the patient and surgeon.

Background

In 1931 Burman2,3 performed a cadaveric elbow arthroscopy and concluded that the elbow was ‘unsuitable for examination’. One year later however after performing 10 arthroscopic procedures he changed his mind and described the elbow as a joint that could be visualized with the arthroscope.3 It took another 50 years before Carson4 demonstrated in a clinical study the utility and safety of elbow arthroscopy.

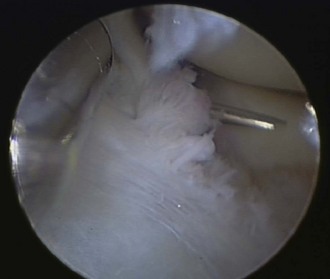

During its infancy, elbow arthroscopy was used primarily for loose body removal and synovectomy.4–10 As experience has grown, techniques and results have been published on using arthroscopy for the excision of osteophytes in arthritis11–14 capsular releases15–18 resection of symptomatic plicae19–21 and the excision of the radial head.22 This expansion in elbow arthroscopic procedures has only occurred since the early 1990s, and is still developing. The improved understanding of the relevant anatomy, and technological advances in instruments and hardware have made elbow arthroscopy significantly safer and have resulted in an expansion of treatment options.

Presentation and investigations

Patients present with disabling stiffness and pain or discomfort. Loss of elbow motion can be significantly disabling. Although Morrey23 described a functional arc of motion as 30 to 130° of flexion, this 100° arc of motion is the arc in which most activities of daily living (ADLs) can be performed. Many activities may require more motion than this, including tying shoes, eating, personal hygiene and sporting activities.

Plain radiographs are required for all patients and should include true lateral and anteroposterior views of the elbow joint. In cases of extreme stiffness it may be difficult to obtain an adequate anteroposterior radiograph. In these cases a computed tomography (CT) scan is required to assess the bony architecture of the elbow and identify calcified loose bodies (Fig. 30.1). In patients with normal X-rays we prefer a CT arthrogram or magnetic resonance (MR) arthrogram. These scans will help identify any cartilaginous or soft tissue blocks and synovial swellings. Often loose bodies, previously undetected can be seen24 (Fig. 30.2).

Preoperative functional assessment scoring is useful to objectively quantify and compare the level of elbow disability, pain and motion. We prefer the elbow functional assessment (EFA) tool and the Mayo performance indicator25 (Table 30.1).

Table 30.1 Elbow functional assessment tool25

| I. Pain (max = 30 points) | |

| Pain sensation at rest (10 cm VAS, no pain is 10 points) | |

| Pain sensation on motion (10 cm VAS _ 2, no pain is 20 points) | |

| II. ADLa (max = 35 points) | |

| Cup to mouth | |

| Eating with a spoon | |

| Lifting a kettle filled with 1 L | |

| Pouring water from a kettle to a glass | |

| Telephone receiver to ipsilateral ear | |

| Cutting with a knife | |

| Pulling an object over the table | |

| III. Motion (max = 35 points) | |

| Active range of motion (max = 25 points) | |

| Active flexion | ≥125° = 15 |

| 100–125° = 10 | |

| 75–100° = 5 | |

| <75° = 0 | |

| Flexion contracture | ≤20° = 10 |

| 20–40° = 5 | |

| ≥40° = 0 | |

| Combined movement (max = 10 points) | |

| Grasping ear lobe of contralateral side with arm in front of the body | Without difficulty = 10 |

| With difficulty = 5 | |

| Impossible = 0 | |

a On a self-reported questionnaire for the ipsilateral arm. Without difficulty = 5; with little difficulty = 3; with much difficulty = 2; with aid = 1; impossible = 0.

Indications and contraindications

The commonest indication is primary osteoarthritis of the elbow, where the causative factors can all be addressed arthroscopically.26 These include osteophytes, capsular contracture, loose bodies, synovitis, joint incongruities and intra-articular adhesions. Pain and stiffness due to posttraumatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, septic arthritis and osteochondritis dissecans can also be treated arthroscopically with excellent results.10,27–31

Jupiter et al described six features of the ‘simple’ stiff elbow.32 This was described for open surgery and elbows that may do well with soft tissue release alone. We have found this guide also useful and applicable for intrinsic stiffness and have modified it to define our indications for arthroscopic treatment of a stiff elbow (Table 30.2).

Table 30.2 Six features of the ‘simple’ stiff elbow (data from Jupiter et al)32

| 1 | Mild to moderate contracture (<80°) |

| 2 | No or minimal prior surgery |

| 3 | No prior ulnar nerve transposition |

| 4 | No or minimal internal fixation/hardware in place |

| 5 | No or minimal heterotopic ossification |

| 6 | Normal bony anatomy has been preserved |

Elbow arthroscopy is not recommended in patients who have undergone previous elbows procedures with changes to the normal anatomy.33 It is also contraindicated in the presence of infection or a non-distensile joint. Gallay et al31 demonstrated that the capsular compliance of stiff elbows is reduced to 15% of normal elbow joints. Therefore, the stiff elbow is already more difficult to access arthroscopically.

Elbow arthroscopy after ulnar nerve transposition remains a relative contraindication. Steinmann et al34 recommend extending the incision for the medial portal to identify and protect the nerve before inserting the arthroscope or instruments. An absolute contraindication for arthroscopic treatment of stiff elbows is a lack of experience with elbow arthroscopy. This procedure can be extremely difficult with a higher risk of nerve injury than other arthroscopic elbow procedures.

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

Position

The supine position was originally described by Andrews and Carson.4 The shoulder is positioned in 90° abduction with the elbow flexed in suspension and held by a traction device. In this position, the anaesthetist has easy access to the patient’s airway. Arthroscopic access to the anterior compartment of the elbow is easy, but the forearm is difficult to mobilize during the procedure due to the traction.

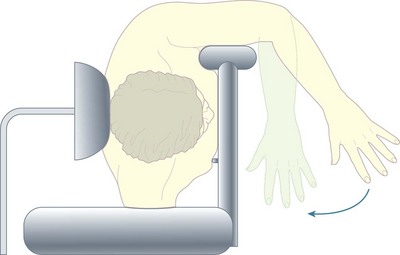

Poehling et al35 described the prone position with the shoulder abducted 90° and the elbow flexed 90°. The advantages of this position are that the elbow is free to move in a sagittal arc range of 0 to about 120° and access to the posterior compartment is easier. The disadvantages are the need to roll the patient and the difficulty to access the airway.

The lateral position (Fig. 30.3) was originally described by O’Driscoll and Morrey.36 It was originally described as an alternative, offering the advantages of the prone position, without the disadvantages. The upper arm, is positioned on a short arm support. We recommend a support designed for elbow arthroscopy, such as the Weston arm holder (Fig. 30.4). This will prevent obstruction of the camera and instruments by the arm holder during the procedure.

Figure 30.3 Lateral position for elbow arthroscopy, allowing full sagittal arc motion and high tourniquet.

(Courtesy of Orthoteers.com.)

Instruments

We prefer to use a 2.9 mm arthroscope with 30° angled lens (Conmed Linvatec) which provides the same wide field of view as a 4.0 mm arthroscope. An end-flow cannula sheath is preferential to a side-flow sheath, particularly for smaller spaces such as the elbow. If a 4.0 mm arthroscope is used, we recommend using a 2.7 mm arthroscope (wrist scope) for the posterior compartment and the radiocapitellar compartment, as these spaces will be narrower than usual in the stiff and arthritic joint (Fig. 30.5)

Both a large and small shaver can be useful and we would recommend having both available for an extensive anterior and posterior debridement and release. Curved shaver blades are extremely useful, but more difficult to triangulate in small spaces. A MacDonald’s retractor, broad trocar or Howarth elevator are useful as capsular retractors as they enable a better view to be obtained during the release procedure (Fig. 30.6).

Portals

The elbow joint is initially inflated with saline to increase the joint volume and aid placement of the arthroscope into the joint. The soft spot is located on the postero-lateral surface of the elbow and is at the centre of a triangle formed by the lateral epicondyle, the radial head and the olecranon. An 18-gauge needle is inserted and the joint distended with 20–40 mL of saline. With distension of the joint the neurovascular structure are displaced anteriorly allowing safer positioning of the instruments (Fig. 30.7).

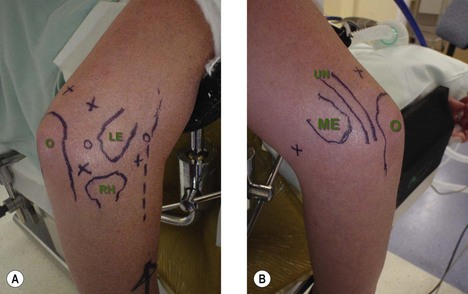

An accurate knowledge of neurovascular anatomy is fundamental to creating safe portals. Prior to proceeding it is essential to palpate the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel and ensure it is not subluxing on elbow flexion or has not previously been transposed. If this is the case then the nerve will need to be identified and protected with a larger incision. The relevant surface anatomy should be marked on the skin, these being the olecranon, radial head, medial and lateral epicondyles, and ulnar nerve. We also mark the course of the radial nerve on the lateral side (Fig. 30.8).

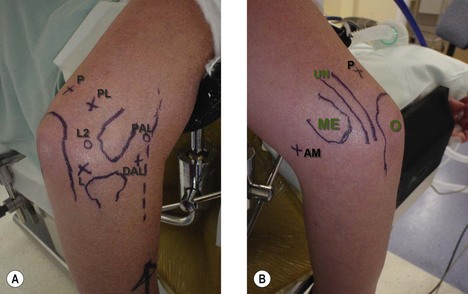

Numerous portals have been described for elbow arthroscopy, of these the most common used are the anterolateral, direct lateral, superomedial, anteromedial, direct posterior and posterolateral37 (Fig. 30.9). Either the medial or lateral portal can be used as the initial portal for the arthroscope. The choice depends on the surgeon’s preference and experience. For arthroscopic debridement and capsular release procedures we prefer the lateral portal for the initial viewing portal. This provides a good view of the coronoid and coronoid fossa, which are two key areas for debridement of elbows with a flexion block.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree