Traumatic Anterior Instability: Open Solutions

Philippe H. Clavert

Peter Millett

Jon J. P. Warner

P. H. Clavert: Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s Hospitals, Boston, Massachusetts.

P. Millett: Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s Hospitals, Boston, Massachusetts.

J. J. P. Warner: Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s Hospitals, Boston, Massachusetts.

THE “GOLD STANDARD”

Arthroscopic treatment of instability has evolved into an accepted method used by many surgeons to treat shoulder instability. This treatment method is now the preference for some surgeons because many recent studies have clearly demonstrated that this type of surgical stabilization procedure is the equal of open capsulolabral repair, as long as the patient selection is appropriate and the surgical procedure is performed with skill.32,78,79,124 Nevertheless, some surgeons choose to treat primary instability with open repair techniques, and, historically, because the success rate with these methods is so proven, it has been called the “Gold Standard.”49,97,134,138

In the case of primary repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability, whether performed arthroscopically or openly, careful preoperative determination of relevant pathology is critical to surgical success. In open repair, there are two basic concepts of surgical stabilization: “anatomical” and “nonanatomical.” In the former group, the surgical philosophy is to repair the capsulolabral injury with a variant of the Bankart and capsular shift procedures. Most surgeons are familiar with these methods, some of whom have revised and modified these methods.4,7,10,49,93,134,138,150,170,178

In the latter group, the surgeon attempts to compensate for capsulolabral injury and bony injury by using procedures, which include the Bristow,62 Latarjet,81 Magnuson-Stack,96 and Putti-Platt procedures121, that substitute for these injured structures. A sequela of these procedures has been loss of motion, higher recurrence rate, and, in some cases, acceleration of arthritis.41,66,74,95,96,101,138 For these reasons, many surgeons in North America tend to avoid them.49,138,184,186 Nevertheless, many series2,8,35,92,159 have reported excellent outcome with some of these procedures, and they may be of value in certain revision situations.

This chapter will present the authors’ preferred indications for open repair in the treatment of primary recurrent anterior instability as well as in the setting of failed prior surgery.

ANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

Mechanisms of Stability: What the Surgeon Should Know

It is important to distinguish “laxity” from “instability.” Laxity is an inherent passive quality of the joint required for the large, full range of motion, which permits overhead use of the shoulder in work, recreation, and sports. Instability

is a dynamic event, which represents the inability of the patient to maintain the humeral head in the glenoid during active shoulder motion.1,17,19,98,104

is a dynamic event, which represents the inability of the patient to maintain the humeral head in the glenoid during active shoulder motion.1,17,19,98,104

Since the larger humeral head is articulated with a smaller glenoid fossa, the surface contact of the glenohumeral articulation represents only a small portion of the humeral head. Indeed, less than one-third of the humeral head articulates with the glenoid; thus the joint is inherently unstable. Factors that control stability are both dynamic and static and function in combination during all aspects of daily living and sport.14,33,56,166,167,171

Many other articles and chapters31,106,164 have elegantly presented these factors, but they will be briefly listed here from their standpoint of surgical relevance in treatment of recurrent anterior shoulder instability.

Static Stability

Static stability is provided by the bony anatomy of the humeral head and glenoid,63,76,91,144,145 as well as the cartilage and labrum, which enhance glenoid depth and breadth.67,91 The glenohumeral joint capsule and its ligaments function as limits to excessive translations and rotations at the end-ranges of joint motion.1,19,116,155,168

Dynamic Stability

Dynamic stability is conferred by the rotator cuff and biceps actively contracting during joint motion. An added level of dynamic stability is also provided by coordinated scapulothoracic motion during glenohumeral motion. This positions the glenoid underneath the humeral head and is important in limiting forces, which might otherwise add to shoulder instability.33,77,85,171 This concept is presented further in the chapter on scapular winging due to serratus anterior palsy.

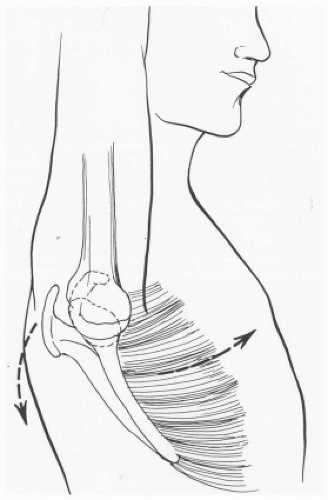

It is very important to understand that static and dynamic factors work together to maintain stability. One example of this is the concept of “Concavity-Compression,” described by Lippitt et al.91 Contraction of the rotator cuff and biceps provide a force that compresses a convex humeral head into a glenoid-labrum articulation with a matched concavity. This may be one of the most important mechanisms of stability during forceful overhead use of the arm.166 As noted previously, proper scapular rotation is imperative to position the glenoid underneath the humeral head to provide a platform on which the humeral head may rotate (Fig. 2-1).

Another mechanism in which static and dynamic factors work together is afferent feedback provided by proprioceptive nerve endings in the joint capsule and tendons, which modulate muscular contraction so that the joint is actively splinted against excessive translation during overhead shoulder motions.86,87

Mechanisms of Instability: What the Surgeon Should Know

Just as normal shoulder stability is an interplay between multiple factors, dynamic and static, instability occurs when the stabilizing structures fail; and this may often involve more than one anatomical structure. Indeed, many studies have observed that instability cannot occur without a combination of dynamic and static failure.5,9,12,146 When traumatic anterior instability occurs, this is usually a sudden explosive event that exceeds the strength of the capsulolabral structures and dynamic stabilizing effect of the intrinsic muscles around the joint. This may be due to a sudden force applied when the ligamentous structures are taught and the muscles are momentarily at a mechanical disadvantage or unable to contract fast enough to splint the joint.17 The result is usually a Bankart lesion; however, many surgeons believe that there is also a significant plastic deformation or stretch of the anterior and inferior joint

capsule.3,9,125,146,163,164,169 Clinically, the degree of plastic deformation is hard to assess. Lippitt et al.,90 in an in vitro study, found no difference in laxity between patients with or without glenohumeral instability.

capsule.3,9,125,146,163,164,169 Clinically, the degree of plastic deformation is hard to assess. Lippitt et al.,90 in an in vitro study, found no difference in laxity between patients with or without glenohumeral instability.

In the majority of cases, a capsulolabral repair can be performed by either arthroscopic or open methods, and many surgeons have accepted the concept of not only repairing the Bankart lesion but also performing some kind of controlled capsular shift as well to deal with capsular stretch.

The rotator interval is the region between the cranial border of the subscapularis tendon and the anterior edge of the supraspinatus.29,30,55,73 The capsular components of this region include the superior and middle glenohumeral ligaments as well as the coracohumeral ligament.14,119 The chapter on multidirectional instability will consider management of capsular lesions and laxity of this portion of the capsule; however, capsular deficiency here has been recognized in the setting of anterior instability.4,10,108,136,170 It is likely that capsular deficiency in this region may be due to a combination of constitutional development (dysplasia of capsular structures) and recurrent trauma with stretching. In any case, when present as a defect, this portion of the capsule should be closed.

Less commonly, pathology may be present in addition to capsulolabral injury, which is significant in recurrence of instability. The relevance of this other pathology is that it may mandate an open treatment approach because anatomical repair using arthroscopic methods cannot restore adequate biomechanical stability. These lesions include glenoid rim fracture,11,128,149,169 glenoid erosion from recurrent instability,11,20,37,72,149,177 capsular rupture and capsular insufficiency after multiple failed surgeries,69,105,126,174 huge Hill-Sachs lesions20,182 (usually in combination with anterior glenoid erosion), and the so-called humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesion.16,141,163,180 Management of each case scenario is discussed in the following text; however, the biomechanical relevance of each is briefly presented here.

Bony Lesions of the Anterior Glenoid

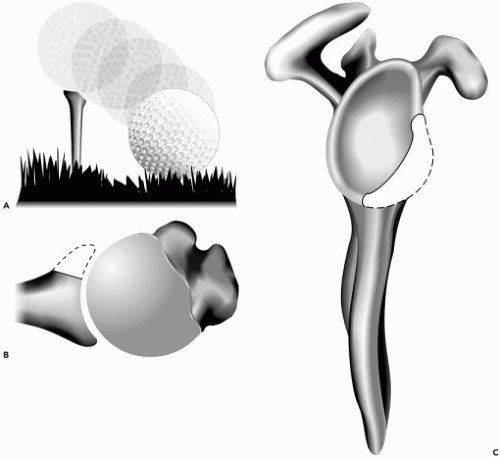

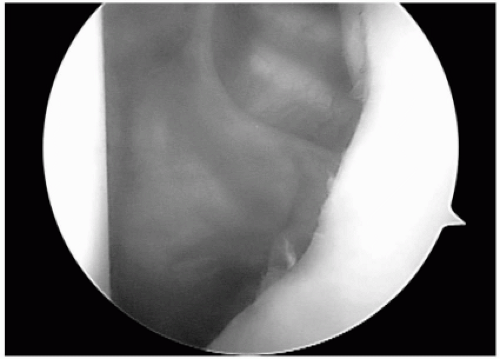

Either an acute traumatic anterior dislocation or recurrent anterior dislocations can cause an associated fracture or erosion of the glenoid rim. The consequence of such an injury is disruption of the normal Concavity-Compression mechanism of joint stability, discussed previously. In effect, the socket of the glenoid looses both its breadth and its depth. Howell and Galinat67 demonstrated that the glenoid socket is enhanced by the labrum and cartilage height, and Lippitt et al.91 demonstrated that this is important for glenohumeral stability (Fig. 2-2). Although Burkhart and DeBeer20 have provided clinical evidence for the consequence of missing this pathology, it seems that most literature has not considered this important factor for glenohumeral stability. Burkhart and DeBeer described the “inverted pear”20 appearance of the glenoid at time of arthroscopy (Fig. 2-3) and found that the recurrence rate of arthroscopic Bankart repair was greater than 80% in contact athletes. They recommended a Latarjet procedure to treat these kinds of patients.

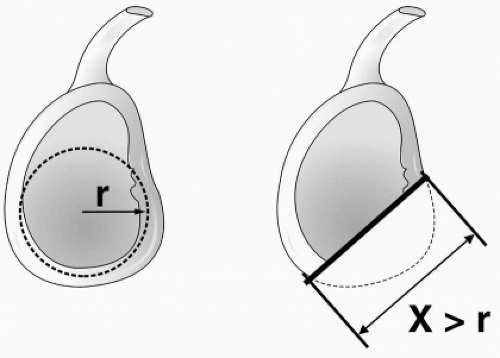

Several other authors20,71 have noted the incidence of anterior glenoid rim erosion being significant in cases of recurrent anterior instability; however, the exact threshold of bone loss, which requires bony restoration of the joint, was not clarified. More recently, Gerber et al.48 provided a quantitative method for determining biomechanically relevant anterior glenoid rim defects (Fig. 2-4). In cases where we suspect glenoid erosion or fracture, we image the shoulder to determine whether such pathology is present and relevant to treatment. This approach is described in the following text.

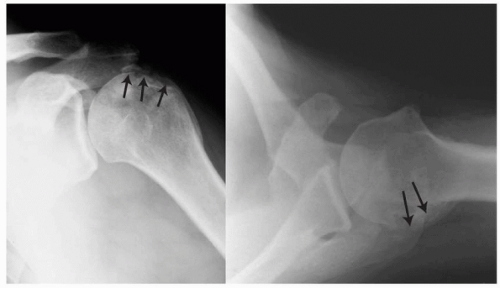

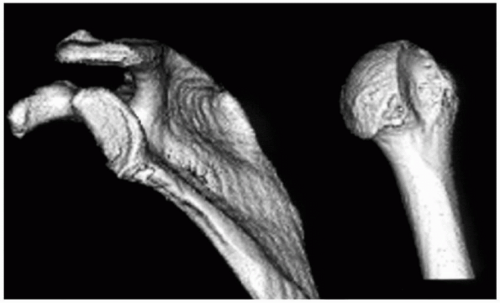

Large Hill-Sachs lesions, which contribute to shoulder instability, are rare. These are usually associated with chronic locked dislocations and accompany an associated anterior glenoid erosion (Fig. 2-5). This pathology requires open stabilization and is considered in the chapter on chronic locked dislocations.

Associated Rotator Cuff Tears

An associated rotator cuff tear can occur with traumatic anterior dislocation and usually occurs in individuals more than 40 years old.140 In the case where this is a tear of the supraspinatus, many surgeons will treat these arthroscopically at the same time that they repair the capsuloligamentous injury arthroscopically; however, complete tears of the subscapularis tendon may be difficult to repair arthroscopically for most surgeons.22 Furthermore, subscapularis insufficiency must be carefully assessed in individuals who have recurrent instability after a failed open anterior repair. In such cases, open surgical repair of the disrupted tendon is appropriate, in addition to capsulolabral repair.

HAGL Lesions

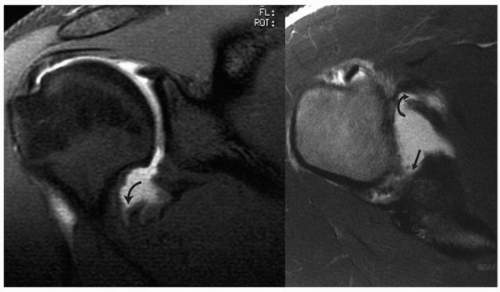

This injury was first recognized and reported as a case report by Bach et al.6 Subsequently, Wolf180 described the arthroscopic identification of this capsular lesion. Bigliani et al.13 studied the pattern of capsular failure with instability and found that a small percentage of experimental traumatic instability is associated with avulsion of the humeral insertion of the inferior glenohumeral ligament and middle glenohumeral ligament. Warner163 and Savoie39 have also recognized the combination of a humeral avulsion of the insertion of the inferior glenohumeral ligament in combination with a concomitant Bankart lesion (Fig. 2-6). Although some surgeons may attempt to repair this HAGL lesion arthroscopically, most prefer open reinsertion of the capsule on the neck of the humerus.

Figure 2-3 An arthroscopic view from the anterior-superior portalshows the anterior-inferior glenoid rim erosion corresponding to Figures 2-2, A and B. |

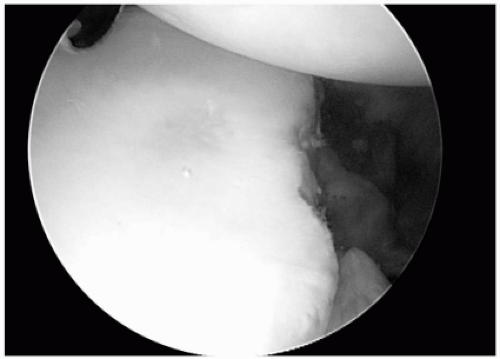

Capsular Rupture

Acute capsular rupture can occasionally occur with traumatic anterior dislocations, but it is quite rare. Bigliani et al.,13 in their experimental instability study, noted this occurrence in only a few cases of anterior dislocation. Occasionally, arthroscopic inspection may demonstrate capsular rupture in some cases of traumatic instability (Fig. 2-7). However, this rare pathology is mostly encountered in the setting of instability after many prior failed repairs, and sometimes after failed thermal capsular shift (Fig. 2-7). In this latter case, it is believed that the capsule is severely damaged by thermal necrosis and then fails with recurrent anterior instability.181 Open surgical repair is required in these cases, which is discussed in the following text.

Figure 2-5 A three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) scan reconstruction demonstrating a severe anterior glenoid erosion (left) and a corresponding large Hill-Sachs lesion (right). |

PATIENT SELECTION FOR OPEN REPAIR

As described previously, careful preoperative determination of pathology is critical in selecting the best method of treatment.20,153,163 Burkhart and DeBeer’s20 observation of such a high rate of recurrent anterior instability, when a glenoid erosion was missed, is evidence supporting this statement.

History

The history given by the patient can often give clues as to the pathology, which may be present. For example, a patient who described a traumatic event as the initial cause of instability and then multiple recurrences with lesser degrees of trauma or no trauma, should be suspected of having severe capsular laxity or loss of anterior glenoid through either fracture or erosion.

The complaint of instability developing by simply placing the arm in a position of abduction should suggest the possibility of constitutional laxity. This concept is discussed further in the chapter on multidirectional instability. Complaint of instability with the arm at the side may be consistent with a rotator interval lesion and multidirectional instability as well.

In some instances, the patient may report a fall with loss of memory but without documented seizure activity. In such cases, a neurological cause should be suspected, and proper consultation with a neurologist is appropriate.

Physical Examination

A detailed discussion of the shoulder examination for instability is beyond the scope and purpose of this chapter. Many other chapters3,99,100 in other textbooks have dealt with this topic, and there are many videos173 available on the subject. Several important findings should be highlighted, however.

The first step of any physical examination should be an adequate neuromuscular assessment because axillary nerve injury is not uncommon with traumatic anterior instability. Moreover, loss of axillary nerve sensation may not be an accurate representation of nerve injury, so it is important to assess motor strength carefully. External rotation strength may be weak due to either an associated rotator cuff tear or a rare suprascapular nerve injury. Visual inspection may also detect atrophy from either rotator cuff tear or nerve injury. In some patients this can be quite subtle.

In the case of documented anterior dislocation, the physical exam should focus on determining other lesions, such as rotator cuff and superior labrum lesions, but it is not necessary to forcefully externally rotate the abducted arm to elicit apprehension. Indeed, dislocation can be caused by such an examination. Assessing active and passive motion, mechanical symptoms, such as catching, and patterns of pain are important. For example, marked weakness of active forward flexion may indicate a rotator cuff tear, and the classic findings of a subscapularis tendon disruption include painful passive external rotation, increased passive external rotation of the adducted shoulder, weak internal rotation, a positive lift-off and belly press sign.46,47 O’Brien117 has described a sign felt to be sensitive for an associated superior labrum injury, pain felt with resisted flexion of the pronated hand but not of the supinated hand. We and others64,148 have found this to be sensitive but not specific for superior labrum tears.

In cases where subtle anterior instability is suspected, when there has not been a documented episode of dislocation, the apprehension and relocation tests are valuable.147 Most surgeons understand how to perform these tests. We perform this test with the patient supine and the arm slowly brought into abduction, external rotation, and extension. Posterior pressure is then applied to the humerus when the patient becomes apprehensive. Speer147 has shown that true apprehension, not simply pain, is required for this test to be specific as well as sensitive.

Inferior laxity is always assessed as well; however, we have found that in an office setting, patients often guard against pain by contracting their muscles, making it difficult to truly assess symptomatic instability. Nevertheless, an observable inferior translation of the humeral head, when the adducted arm is pulled inferiorly, suggests inferior instability, which is the hallmark of multidirectional instability.108,109 If such inferior laxity and symptoms are observed when the arm is in external rotation as well, this suggests pathologic laxity of the rotator interval capsular region.27,38,61,150,156,175

Imaging

Plain Radiographs

Orthogonal views of the shoulder are very important to document the direction of instability and to look for relevant osseous lesions. A standard trauma series, which we employ, consists of a true anterior-posterior view of the glenohumeral joint with the shoulder in internal and external rotation, an axillary view (standard or West Point), and a Stryker-Notch view.123,129,130 The combination of these views has been shown to be very accurate for detecting glenoid fractures and Hill-Sachs lesions123 (Fig. 2-5). The appearance of static anterior subluxation of the

humeral head on the axillary radiograph should suggest severe disruption of the glenoid concavity or a subscapularis rupture (Fig. 2-8). In some cases, an associated anatomic neck fracture or greater tuberosity fracture, which is not displaced, may be identified as well (Fig. 2-9). Furthermore, inferior dislocation of the adducted humerus, the so-called subglenoid dislocation, has a high association with rotator cuff tears (Fig. 2-10).

humeral head on the axillary radiograph should suggest severe disruption of the glenoid concavity or a subscapularis rupture (Fig. 2-8). In some cases, an associated anatomic neck fracture or greater tuberosity fracture, which is not displaced, may be identified as well (Fig. 2-9). Furthermore, inferior dislocation of the adducted humerus, the so-called subglenoid dislocation, has a high association with rotator cuff tears (Fig. 2-10).

Three-Dimensional Imaging

If the surgeon considers the range of pathology described previously, it will be impossible to detect all lesions simply using two-dimensional plain radiographs. In all cases, we perform additional imaging to better visualize the three-dimensional nature of the injury. This is either by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or by computed tomography (CT).

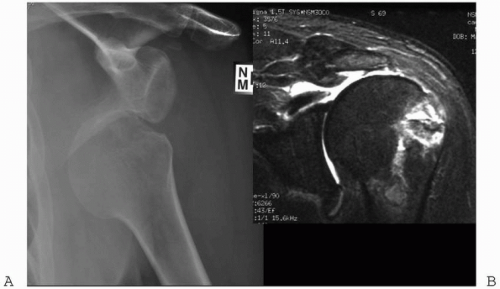

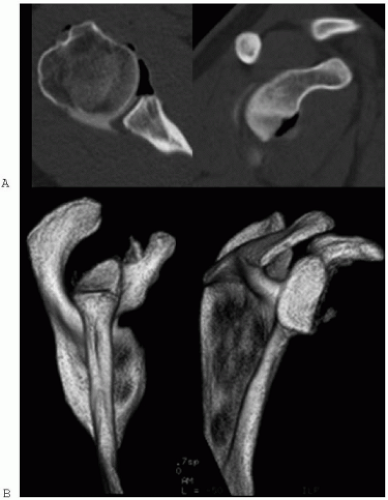

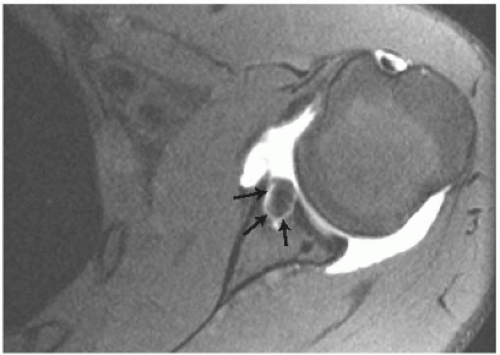

Magnetic resonance imaging is ordered with intra-articular gadolinium in cases where a capsulolabral injury is suspected. Bankart lesions and superior labrum anterior posterior lesions (SLAP) may be accurately identified, but, occasionally, HAGL lesions and capsular ruptures are also identified (Fig. 2-6). Furthermore, anterior glenoid fractures and erosions may also be seen (Fig. 2-11); however, we do not feel that quantitative assessment of the degree of bone loss is always accurate with this method. Moreover, in the case of failed prior surgery where metal or absorbable anchors have been placed in the anterior glenoid, artifact signal may obscure the degree of glenoid injury (Fig. 2-12). In cases where an anterior glenoid lesion and/or a large Hill-Sachs lesion are suspected, we obtain a CT-arthrogram.51,70,80,143

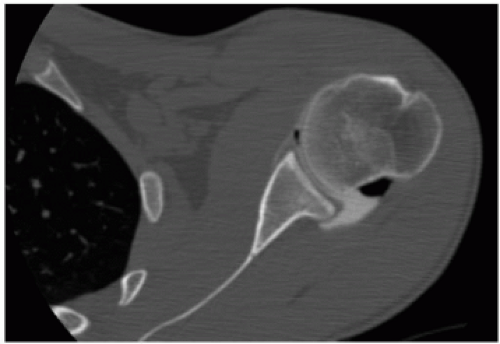

A CT-arthrogram will accurately define the glenoid articular surfaces because the dye will outline cartilaginous erosion (Fig. 2-13). In some circumstances, a three-dimensional reconstruction can give more accurate representation of the degree of osseous injury.

Method for Assessing Anterior Glenoid Erosion

Gerber et al.48 have demonstrated a method of measuring either oblique sagittal images of the glenoid surface or three-dimensional reconstructions of the glenoid surface (Fig. 2-4). In this method, if the length of the glenoid defect exceeds the maximum radius of the glenoid, then the force required for anterior dislocation is reduced by 70% from an intact glenoid. In such cases, a standard Bankart repair is likely to fail, and some kind of bony augmentation is recommended.

Radiographic evaluation should include plain radiographs. Magnetic resonance imaging or CT with contrast can demonstrate labral tears, capsular injuries, or bony deficiencies. Patients with concomitant glenoid fractures, large Hill-Sachs lesions, or bony erosions will benefit from three-dimensional reconstruction of the glenoid for preoperative planning. These imaging studies are also needed to identify coexisting pathology (i.e., rotator cuff tears), the degree of capsular laxity, and the extent of labral pathology preoperatively so that the appropriate surgical procedure can be selected and planned.51,70 Computed tomography is preferred if osseous pathology is suspected.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR OPEN ANTERIOR STABILIZATION—AUTHORS’ PREFERENCE

In most cases, traumatic anterior instability is associated with a Bankart lesion with some degree of associated capsular stretch. In these cases, we prefer to perform arthroscopic capsulolabral repair. This surgical technique is discussed in another chapter. In some cases where there is constitutional laxity and prior arthroscopic surgery has failed, we then perform an open capsular shift. In cases

where there is significant anterior glenoid erosion, according to the criteria described previously, we perform an osseous reconstruction. In rare cases, when we feel a huge Hill-Sachs lesion is playing a role in instability recurrence, open surgery is performed as well. When there is a significant disruption of the subscapularis, usually in the setting of prior surgery, an open repair is performed.

where there is significant anterior glenoid erosion, according to the criteria described previously, we perform an osseous reconstruction. In rare cases, when we feel a huge Hill-Sachs lesion is playing a role in instability recurrence, open surgery is performed as well. When there is a significant disruption of the subscapularis, usually in the setting of prior surgery, an open repair is performed.

Figure 2-11 (A) A severe anterior glenoid rim erosion is demonstrated on standard axial CT and oblique-sagittal reconstruction as well (B) as on a three-dimensional reconstruction. |

Figure 2-12 An artifact due to an anterior anchor in the glenoid (arrows) obscures articular anatomy on this MRI arthrogram. |

Figure 2-13 A CT-arthrogram of a normal joint demonstrates congruity of the articular surfaces with a normal concavity-convexity match. |

In cases of concomitant severe arthritis, open instability repair may not be effective. Depending on the status of the osseous glenoid and surrounding rotator cuff, arthroplasty or arthrodesis may be more appropriate. Paralysis may also be associated with chronic instability and, in such cases, arthrodesis may be more successful in eliminating pain.26,36,50,132

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree