Transmetatarsal Amputation

James Brodsky

Nathan Bruck

Transmetatarsal amputation (TMA) is the partial foot amputation that is most easily accommodated in footwear, requiring the least complexity in terms of special insoles and modification of footwear (1, 2, 3 and 4). It has the limitation of being applicable only for cases with the most distal level of trauma or dry or wet gangrene. Many patients with infection or local tissue death have involvement far too extensive to be treated with this procedure. Choosing this procedure inappropriately only condemns the patient to additional, possibly unnecessary operations. The choice of a TMA should be made based on examination and diagnostic studies, but the presence of margins of bleeding and viable tissue at the time of closure is not only particularly important but also an easily applied clinical criterion.

If the amputation is done through the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joints themselves, rather than more distally at the transmetatarsal level, the nature of the amputation and the function of the residual foot are significantly altered. The loss of the attachments and thereby the functions of the peroneus brevis, peroneus longus, and the tibialis anterior tendons create a less functional foot with a notable muscle imbalance. The triceps surae, through the attachment of the Achilles tendon, gradually produce an equinus deformity of the ankle. If a TMA is extended proximally and thus converted to a Lisfranc TMT disarticulation, the surgeon should try to transfer the insertions of the midfoot tendons proximally to the residual skeletal structure. In addition, it is usually advisable to lengthen the Achilles tendon at the same time.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The primary indication for a TMA is the presence of nonviable toes with or without loss of viability of the most distal forefoot. In practice, this usually translates into the clinical diagnosis of gangrene. Distal forefoot means involvement of tissue no more proximal than the distal one half of the metatarsals. The multiple or variable causes of the gangrene include, but are not limited to, diabetes, arteriosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, nondiabetic peripheral neuropathy, severe trauma, and embolic phenomena from sepsis or other causes.

The most common indications for TMA, in decreasing order of frequency, are diabetic foot problems, vascular insufficiency in the absence of diabetes, and trauma. Because many of these procedures are done because of tissue death due to poor circulation, a special set of circumstances are presented with regard to the applicability of the operation. Patients who need the amputation because of trauma (e.g., from a boating accident) or because of embolism frequently do not have the problems with healing that the former group demonstrates.

TMA may be a good procedure to salvage other, more distal procedures that have failed. Examples include failed toe amputations that have not healed because of inadequate circulation or persistent infections, recurrent soft tissue breakdown, ulceration, or severe metatarsalgia after resection of two or more rays (i.e., metatarsal plus corresponding toe).

This operation is also indicated as a salvage procedure in selected diabetic or other patients with insensitive feet, who have recurrent neuropathic ulcerations, even in the absence of the other factors of infection, gangrene, or vascular insufficiency discussed earlier. These patients also may be candidates for a modified Hoffmann procedure to remove all of the lesser (and possibly the first) metatarsal heads. A patient may be a candidate who has had two or three metatarsal heads resected for recalcitrant ulceration or localized infection, now resolved, who is experiencing yet another ulceration

because of the concentration of loading on the remaining metatarsals. Although a modified Hoffmann procedure has the advantage of saving the toes, these toes are “floppy” and can be subjected to other recurrent infection and pressure in the shoe, especially if they are elevated by contraction of dorsal scars. The patient with a TMA, especially if it is a proximal one, may have more difficulty in holding a shoe on, but the procedure obviates the risk of further recurrent toe lesions.

because of the concentration of loading on the remaining metatarsals. Although a modified Hoffmann procedure has the advantage of saving the toes, these toes are “floppy” and can be subjected to other recurrent infection and pressure in the shoe, especially if they are elevated by contraction of dorsal scars. The patient with a TMA, especially if it is a proximal one, may have more difficulty in holding a shoe on, but the procedure obviates the risk of further recurrent toe lesions.

Age is not an important factor in patient selection for the procedure, provided that the general criteria of adequate perfusion and preexisting ambulatory function are met. Patients with an equinus contracture should not have a TMA because of the excessive pressure applied to the end of the stump by the plantarflexed ankle, unless a concomitant Achilles lengthening is done. If the equinus deformity is of recent onset and is still relatively flexible (i.e., not yet a true fixed contracture), the procedure can be followed by stretching by placement of the limb in serial holding casts or by the use of a dorsiflexion ankle-foot orthosis. However, it is easier, and rather prophylactic, to proceed with Achilles lengthening at the time of the TMA. Occasionally, a severe equinus contracture may require release of the posterior ankle and subtalar joint capsules as well. The surgeon should decide if it is worth performing extensive soft tissue releases to provide a plantigrade foot with a TMA, especially if the release requires flexor tendon lengthening. In this case, it may be better to do a more proximal amputation.

TMA is not indicated for the nonambulatory patient when the level of healing is doubtful. For a patient who cannot weight bear because of paralysis, dementia, or severe debility, a more proximal amputation is indicated if the diminished circulation makes the prospect of healing questionable. One of the principal indications for the TMA is to preserve the length of the foot so that the patient has maximum potential walking and mobility and can wear an easily modified shoe rather than a prosthesis.

Another contraindication for a TMA is extensive gangrene or infection of the plantar skin (i.e., more proximal plantar than dorsal soft tissue loss) because of the loss of the plantar flap, which is most often used to cover the end of the resected bones. It is relatively contraindicated in patients who have little or no function of the anterior compartment and lateral compartment muscles to oppose the pull of the triceps surae. In these patients, it is necessary to do lengthening of the Achilles tendon, and the permanent use of a polypropylene ankle-foot orthosis will be required. Even with these caveats, this procedure is still preferable to a proximal amputation, which requires the use of a prosthesis. It is relatively contraindicated in patients who have instability or deformity at Lisfranc joint, especially diabetics with peripheral neuropathy who have had a Charcot midfoot joint.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

In diabetic and in nondiabetic dysvascular patients, it is essential to evaluate the preoperative vascular status of the limb (5). As in all cases of amputation surgery, the foot should be carefully examined to determine adequacy of vascularity and integrity of the skin. The foot should be palpated to detect the presence of posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses. Additional diagnostic studies may be useful, particularly in the patient with nonpalpable pulses. Screening is most easily and most widely done using the Doppler ultrasound. The ankle-brachial index (ABI) is determined by measuring the ankle systolic pressure and dividing it by the brachial systolic pressure using Doppler detection of the pulse. The severity of arterial disease is relative to decreasing values of ABI, and a value less than 0.45 or 0.50 is considered abnormal in diabetics. However, this is only a screening test, and there are valid questions regarding the sensitivity and specificity and predictive value of the test (5,6). It is only a test. It may underestimate the severity of the arterial insufficiency. The ABI is affected by upper extremity disease and even more by stiff, calcified vessels in the lower extremity, which are common in diabetics. These lead to falsely elevated values of the ABI. When additional evaluation is required in patients with marginal vascularity, a vascular surgery consultation may be considered and other testing may be performed, such as arteriography. The vascular surgeon may also provide an opinion regarding the role of preoperative revascularization.

Transcutaneous oxygen tension measurement (TcPO2) has been advocated as useful for evaluation of the viable level of amputation. The amputation is likely to heal at the level tested if the TcPO2 is greater than 20 mm Hg. The TcPO2 depends on the temperature, and an electrode surface temperature of 44°C to 45°C is considered a standard testing condition. It is a slow and often difficult to standardize test, exacerbated by being temperature dependent.

The absolute toe systolic pressure measurement is the most useful and practical noninvasive vascular study that has been used as a predictor for amputation in diabetics with foot ulcers. Values less than 40 mm Hg can be considered abnormal, but healing may occur with values between 30 to 40 mm Hg.

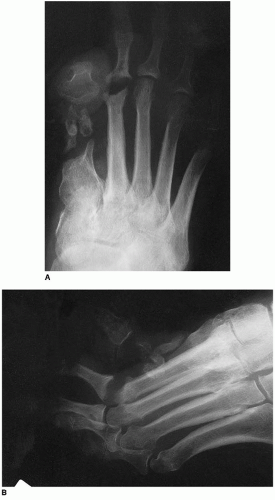

Radiographs are important in the preoperative routine planning to rule out the extension of osteomyelitis to a level that might preclude the use of this amputation (Fig. 16.1). Other special studies to

determine the presence and extent of deep infection may be useful such as the technetium bone scan combined with a white cell-labeled indium scan, or, occasionally, a magnetic resonance imaging. The latter may be falsely positive if there are changes of Charcot neuroarthropathy, a condition in diabetics that predominately affects the midfoot (7).

determine the presence and extent of deep infection may be useful such as the technetium bone scan combined with a white cell-labeled indium scan, or, occasionally, a magnetic resonance imaging. The latter may be falsely positive if there are changes of Charcot neuroarthropathy, a condition in diabetics that predominately affects the midfoot (7).

As noted above, it is important to examine the patient for a preoperative equinus contracture. This is frequently a subtle finding, and the testing needs to be done with the knee both in flexion and extension positions, to distinguish between a tight Achilles tendon and a gastrocnemius contracture. Release may be of one or both, depending on physical findings. Also worthy to note is the presence of forefoot equinus that is in addition to and separate from the ankle equinus. Forefoot equinus is caused by plantarflexion contracture at Chopart joint (i.e., calcaneocuboid and talonavicular joints), and this is frequently overlooked.

The TMA is not commonly performed, but it is not technically difficult. Like all operative procedures, proper attention to detail enhances the quality of the result. Gentle handling of the soft tissues, especially in diabetic and dysvascular patients, should be practiced. This translates into gentle retraction and minimal handling of the skin edges with the forceps.

TMAs may be performed at different levels or length. In general, it is preferable to produce the longest possible stump that is likely to heal with primary closure of the soft tissue. It is not worthwhile to try to create a slightly longer stump if the skin and soft tissue will be closed under tension or if the edges are not viable.

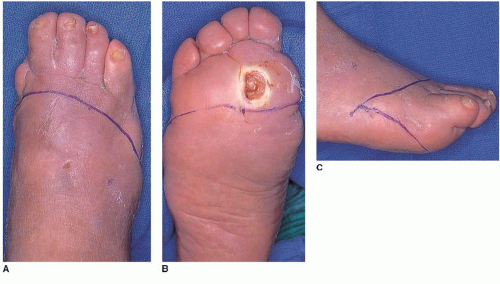

It is helpful to plan the flaps with a skin marker, designing a longer plantar flap to correspond to the length of the residual metatarsals. These are basically fish-mouth flaps, as illustrated in Figure 16.2. Although these can be of various lengths, the relative proportion is roughly the same. The plantar flap is generally longer, so that it can wrap up and around the end of the stump. The plantar flap should be long enough to bring the suture line to the dorsal-distal stump. It is also helpful to angle the contour of the flaps slightly from medial-distal to lateral-proximal, so that the lateral side of the soft tissue flaps is slightly shorter, corresponding to the pattern of bone resection described below.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

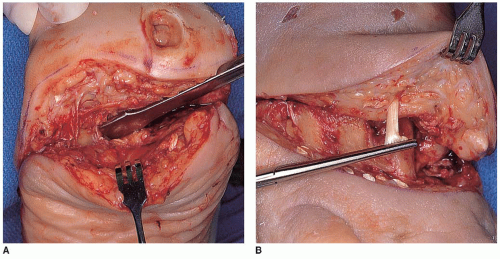

Full-thickness flaps are developed with incisions extending from the skin level down to the bone (Fig. 16.3A). The dorsal flap is fashioned first. Using a large blunt elevator, the soft tissue is elevated in a proximal direction beneath the flap (Fig. 16.3B). The interosseous muscles are not yet divided because they are located between the metatarsals below the level of the dorsal cortices. At this point, the dorsalis pedis artery is usually ligated.

The plantar flap is fashioned next. In a long or more distal TMA, the flap begins at the base of the toes on the plantar foot. The incision is carried down to the bone, and soft tissue dissection is performed with an elevator right on the level of the plantar cortices of the metatarsal shafts to create a full-thickness flap (Fig. 16.4A). Hemostasis is usually achieved with electrocautery at this level.

FIGURE 16.4 A: The plantar flap is developed with a similar incision down to the bone and then dissected as a single flap. The plantar flap is thicker than the dorsal flap, which may require thinning (see Fig. 16.6). B: Tension is placed on the flexor and extensor tendons with a clamp, which are then divided, allowing them to retract; the extensor tendons are shown here.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree