Total Hip Arthroplasty in Very Young Patients

Muyibat A. Adelani

Gregory G. Polkowski

John C. Clohisy

Total hip arthroplasty is an effective treatment for end-stage hip disease, and is known to dramatically improve pain and function of affected patients. Although originally intended for use in elderly, low-demand patients, total hip replacement can also offer symptomatic relief to younger patients who develop advanced hip disease early in life. Nevertheless, total hip arthroplasty in very young patients (30 years of age or less) warrants special considerations, because of the spectrum of diseases affecting the hip in this population, deformities that may accompany these conditions, and the need for long-lasting results from surgical intervention. This chapter will review the etiology of hip failure in young patients, discuss perioperative considerations unique to total hip arthroplasty in this population, and summarize clinical outcomes.

End-Stage Hip Disease in the Very Young Patient

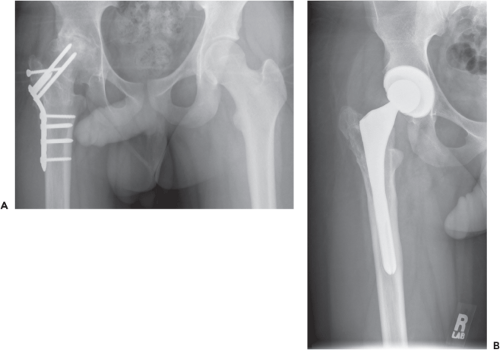

Historically, total hip arthroplasty was performed in young patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In fact, a significant number of reports in the orthopedic literature on total hip arthroplasty in young patients focus on this population (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9). However, with the advent of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, this group of patients is less frequently encountered. Modern case series demonstrate that avascular necrosis and secondary osteoarthritis (related to developmental dysplasia of the hip or other sequelae of childhood hip conditions, such as slipped capital femoral epiphysis, Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease, or septic arthritis) have become more frequently reported than rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 76.1) (10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17). Less frequently encountered diagnoses include other inflammatory arthropathies like ankylosing spondylitis and rare skeletal dysplasias such as spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia. See Table 76.1 for a complete summary of diagnoses.

Preoperative Considerations

The primary goals of total hip arthroplasty—pain relief and improved function—continue to be priority, despite the patient’s young age. However, functional goals in this population can widely vary from those of the typical hip replacement patient. Although some young patients may be limited because of their underlying conditions (i.e., polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis or the minimally ambulatory patient with cerebral palsy and acetabular dysplasia), most patients 30 years of age or less are typically very active, continuing to pursue school, work, and/or recreation (18,19,20). An essential preoperative task is patient education. It is important that young patients have appropriate expectations regarding the function and the durability of their prosthetic hip. In general, patients should be discouraged from participating in activities which put the hip at risk for early failure. Specifically, they should expect to limit high-impact activities in favor of activities like swimming and biking, to maximize the life of the implant (20,21,22). But even with activity modification, young patients should expect to have at least one revision arthroplasty in their lifetime, as the average life expectancy exceeds typical THA survivorship (23,24).

An important secondary objective specific to total hip arthroplasty in young patients is bone and soft tissue preservation. Conservation of surrounding bone and soft tissues is crucial to hip function and the success of future surgeries, as there is a high likelihood of revision arthroplasty in this population. This goal may be complicated by the presence of deformity as well as previous surgeries. Thus, the complexity of THA in young patients demands a careful preoperative surgical plan, often more comprehensive than templating for a typical THA.

Deformities, such as acetabular deficiency, proximal femoral deformity, and leg-length discrepancy, are not uncommon in this population (Fig. 76.2) (8,9,25,26,27). In addition, young patients frequently have undergone previous surgery, potentially leading to retained hardware, scarring, and heterotopic ossification about the hip (11,15,17,19,28). Such hips may suffer from abductor deficiency, osteopenia, and/or severe joint stiffness, further complicating the planned arthroplasty procedure. All of these circumstances need to be identified preoperatively. Physical examination, plain radiographs, and occasionally, advanced imaging, can be helpful in that regard.

Once any of the aforementioned conditions are identified, they must be addressed in the surgical plan. Any previous

incisions about the hip should be identified, as previous approaches to the hip can give clues as to the condition of the underlying soft tissues. Use of previous incisions depends on the exposure needed, which is often dictated by other circumstances, such as heterotopic ossification, retained hardware, and the need for a more extensile approach of the pelvis or femur to treat associated deformities or any anticipated complications. Extensive heterotopic ossification from a previous surgery suggests a propensity for more bone formation after arthroplasty. Consideration may be needed for pre- or postoperative radiation or medical prophylaxis. Retained hardware often necessitates additional equipment for removal, which should be requested. In addition to standard small and large fragment sets, burrs and trephines should also be available to help remove incarcerated or broken implants. Pre-existing bony deficiencies may require additional procedures to accommodate THA. For example, in cases of acetabular dysplasia or severe acetabular protrusio, bone graft materials may be necessary to supplement implant fixation and/or restore bone stock. Severely dysplastic hips associated with complete dislocation may require a shortening subtrochanteric femoral osteotomy to bring the hip center down to the newly implanted acetabular component (Fig. 76.3). Hips with proximal femoral deformity may also require an osteotomy to correct the angular deformity to allow for instrumentation of the femoral canal with a straight stem. Patients with marked osteopenia, such as those with osteogenesis imperfecta, or those with retained femoral hardware that is being removed at the time of arthroplasty, have a high risk for intraoperative fracture, which must be addressed, should it occur. Thus, a surgical plan should be created in anticipation of such circumstances. A surgical approach should be selected that is extensile

and allows access to the pelvis and femur. Any additional equipment, such as allograft bone, porous metal augments, cables, plates, and sagittal saws, may need to be requested in advance.

incisions about the hip should be identified, as previous approaches to the hip can give clues as to the condition of the underlying soft tissues. Use of previous incisions depends on the exposure needed, which is often dictated by other circumstances, such as heterotopic ossification, retained hardware, and the need for a more extensile approach of the pelvis or femur to treat associated deformities or any anticipated complications. Extensive heterotopic ossification from a previous surgery suggests a propensity for more bone formation after arthroplasty. Consideration may be needed for pre- or postoperative radiation or medical prophylaxis. Retained hardware often necessitates additional equipment for removal, which should be requested. In addition to standard small and large fragment sets, burrs and trephines should also be available to help remove incarcerated or broken implants. Pre-existing bony deficiencies may require additional procedures to accommodate THA. For example, in cases of acetabular dysplasia or severe acetabular protrusio, bone graft materials may be necessary to supplement implant fixation and/or restore bone stock. Severely dysplastic hips associated with complete dislocation may require a shortening subtrochanteric femoral osteotomy to bring the hip center down to the newly implanted acetabular component (Fig. 76.3). Hips with proximal femoral deformity may also require an osteotomy to correct the angular deformity to allow for instrumentation of the femoral canal with a straight stem. Patients with marked osteopenia, such as those with osteogenesis imperfecta, or those with retained femoral hardware that is being removed at the time of arthroplasty, have a high risk for intraoperative fracture, which must be addressed, should it occur. Thus, a surgical plan should be created in anticipation of such circumstances. A surgical approach should be selected that is extensile

and allows access to the pelvis and femur. Any additional equipment, such as allograft bone, porous metal augments, cables, plates, and sagittal saws, may need to be requested in advance.

Table 76.1 Indications for THA in Patients 30 Years of Age and Younger—Review of the Literature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|