10

Thoracic Syndrome

Definition and Prevalence

Definition and Prevalence

The term “thoracic syndrome” refers to all pathological clinical manifestations due to functional disturbances and degenerative changes of the thoracic motion segments.

The term “thoracic syndrome” refers to all pathological clinical manifestations due to functional disturbances and degenerative changes of the thoracic motion segments.

Disk disease is far less common in the thoracic spine than in the cervical and lumbar regions. Thoracic disk disease accounts for only 2% of all cases of disk disease and tends to be less serious than disk disease elsewhere in the spine. Thoracic nerve root irritation producing intractable intercostal neuralgia is a rare surgical indication. Massive disk prolapse resulting in spinal cord compression (occasionally even paraplegia) is also a rare event (Grote 1975, Awwad et al. 1991, Dietze 1993, Wilke et al. 2000, Borenstein et al. 2004, Endres 2005). Even though the degenerative process affects all disks in the spine, and the thoracic disks perhaps even more so than others, thoracic disk disease remains rare because of the special anatomical and biomechanical features of the thoracic motion segments.

Special Anatomy, Biomechanics, and Pathoanatomy of the Thoracic Motion Segments

Special Anatomy, Biomechanics, and Pathoanatomy of the Thoracic Motion Segments

Special anatomy. The thoracic disks become broader and higher toward the lower end of the thoracic spine. They are flatter than the cervical and lumbar disks in terms of the ratio of width to height. The thoracic spinal canal is relatively narrow, with only a thin epidural space between the spinal cord and the surrounding bone or disk. The canal is narrowest from T4 to T9.

The thoracic spine contains not only the intervertebral joints, but also the joints between the vertebral bodies and ribs, i.e., the costotransverse joints, which indent the lower portion of the intervertebral foramina; their upper portion is occupied by the exiting spinal nerve. Bony narrowing of the intervertebral foramina, such as is seen in the cervical spine,is hardly ever seen in the thoracic spine because the thoracic foramina are much wider.

In the thoracic spine, as in the cervical spine, the spinal cord segments become increasingly distant from the correspondingly numbered motion segments as one proceeds from cranial to caudal. This distance is the equivalent of two segments from T1 to T6, and of three segments from T7 to T10.

The ventral branches of the thoracic spinal nerves, i.e., the intercostal nerves, supply the wall of the rib cage: in particular, they supply the intercostal muscles, the costotransverse ligaments, the parietal pleura, and the skin. Irritation of a thoracic spinal nerve causes intercostal neuralgia.

Biomechanics and pathoanatomy. The dorsally convex curvature of the thoracic spine places the ventral portion of the thoracic motion segments under greater stress. The intradiscal pressure here is very high. In the lordotically curved cervical or lumbar spine an axial compressive force can be borne to a large extent by the intervertebral joints and interlaminar soft tissue, but in the thoracic spine the vertebral bodies and disks must bear the entire burden. This explains the frequency of thoracic vertebral compression fractures and of protrusions of disk tissue through the vertebral body end plates into the spongiosa. The continuously high intradiscal pressure induces premature regressive changes, particularly in the middle and lower thoracic disks, often involving extensive spondylosis and osteochondrosis. These changes are usually noted incidentally on radiological studies and are all the more surprising because they are asymptomatic. In the thoracic spine even more than elsewhere, spondylosis and osteochondrosis can be quite advanced, radiologically speaking, but still clinically insignificant. Symptoms arise only when these processes take place in the immediate vicinity of a nerve root, and when the motion segment is unstable. These preconditions are not present in the thoracic spine.

There are essentially two reasons why clinically significant disk disease is less common in the thoracic spine than elsewhere:

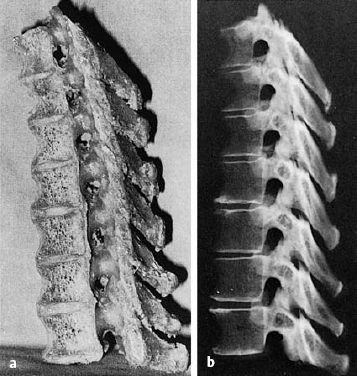

In the thoracic spine, as opposed to the cervical or lumbar spine, the intervertebral foramina are not located directly behind the disks, but rather at the level of the vertebral body (Fig. 10.1). Only a very large thoracic disk prolapse would be able to work its way upward or downward far enough to contact a spinal nerve root. In this rare event, the clinical manifestations of a thoracic disk syndrome may be produced, i.e., intercostal neuralgia.

In the thoracic spine, as opposed to the cervical or lumbar spine, the intervertebral foramina are not located directly behind the disks, but rather at the level of the vertebral body (Fig. 10.1). Only a very large thoracic disk prolapse would be able to work its way upward or downward far enough to contact a spinal nerve root. In this rare event, the clinical manifestations of a thoracic disk syndrome may be produced, i.e., intercostal neuralgia.

The thoracic motion segments move relatively little compared to the cervical and lumbar motion segments. Thus, the anatomical relationship of the sensitive neural structures to their surroundings, i.e., of the spinal nerves to the bone and connective tissue around them, remains relatively constant.

The thoracic motion segments move relatively little compared to the cervical and lumbar motion segments. Thus, the anatomical relationship of the sensitive neural structures to their surroundings, i.e., of the spinal nerves to the bone and connective tissue around them, remains relatively constant.

Fig. 10.1 a, b Parasagittal section of the mid-thoracic spine. The intervertebral foramina are not at the level of the disks, as in other regions of the spine (see Figs. 9.12, 11.3 ), but rather at the level of the vertebral body.

Acquired deformities of the thoracic spine (scoliosis, Scheuermann disease) develop gradually, allowing the nerve roots enough time to adapt.

Acquired deformities of the thoracic spine (scoliosis, Scheuermann disease) develop gradually, allowing the nerve roots enough time to adapt.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree