15

Exercise in a Pain-Free Range of Motion

| Exercise and Nociception | 331 | EPFRM Units | 333 |

| Which Exercises are Suitable? | 332 |

The concept of exercise in a pain-free range of motion (EPFRM) is based on the observation that exercise reduces pain. The exercise must not be of a type that worsens pain, i.e., parts of the body should be exercised that are not affected by the pain-producing process. In patients with severe, chronic pain at multiple sites, only a few parts of the musculoskeletal system can be activated without pain, and such individuals typically stop doing practically any physical activity, particularly sports and gymnastics. Patients with back pain and arthrosis, too, say things like, “Because of the pain, I’ve had to give up all types of sports, even my favorites, as they all make the pain worse.”

On the other hand, patients with pain commonly state that they have less pain overall when they are more physically active. They find, by experience, which kinds of movement are good for them and do not give rise to further pains that persist even after the activity is over. Thus, the first rule of back school is, “Thou shalt exercise.”

Controlled studies have shown that patients with acute low back pain are more likely to become pain-free if they exercise than if they rest in bed (Coomes 1961, Gilbert 1985, Deyo 1986, Postacchini 1998, Szpalski 1992, Malmivaara 1995, Wilkinson 1995). Exercise therapy integrated into a multimodal program is successful in patients with chronic back pain (Hildebrand 1994, Pfingsten 1997).

Exercise and Nociception

Exercise and Nociception

As long as exercise does not itself produce pain, it has multiple positive effects on the process of nociception in the musculoskeletal region (Table 15.1):

The increased perfusion accompanying all types of exercise promotes the peripheral degradation of inflammatory mediators.

The increased perfusion accompanying all types of exercise promotes the peripheral degradation of inflammatory mediators.

Muscle activity increases the transport of metabolic waste products out of the muscle tissue.

Muscle activity increases the transport of metabolic waste products out of the muscle tissue.

Patterns of movement that are beneficial for the spine and joints bring about positive changes in the central nervous pathways for nociceptive impulse conduction and processing.

Patterns of movement that are beneficial for the spine and joints bring about positive changes in the central nervous pathways for nociceptive impulse conduction and processing.

Neutralizes the effect of pain-producing substances by dilution Neutralizes the effect of pain-producing substances by dilution |

Quiets the activity of the nervous system’s nociceptive pathways Quiets the activity of the nervous system’s nociceptive pathways |

Promotes the secretion of endorphins Promotes the secretion of endorphins |

Defuses pain-promoting emotional processes and distracts from the pain Defuses pain-promoting emotional processes and distracts from the pain |

| “Exercise your pain away!” |

The latter is implied both by the gate control theory of pain and by the known mechanisms of neural plasticity. Exercise, like antalgic medication, can dampen or even totally interrupt the conduction and processing of nociceptive impulses.

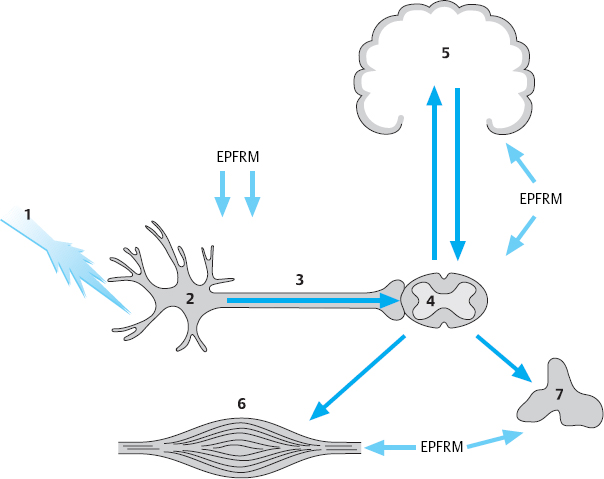

Exercise above a certain level of intensity causes the release of endogenous pain-relieving substances. The activation of endorphinergic neurons leads to the development of pain tolerance, ranging all the way to analgesia (Fig. 15.1).

Endogenous opioid peptides activate peripheral opioid receptors and inhibit nociception in damaged tissue. Endorphins travel from their site of production to their target organs in the same way as hormones. They inhibit the release of nociceptive neurotransmitter substances, such as substance P, thereby reducing the number of nociceptive action potentials traveling to higher centers. Synaptic activity, with excessive excitation of nociceptive neurons due to a high intracellular calcium concentration, is reduced (Waldvogel 1996).

The most important benefit of exercise in a pain-free range of motion (EPFRM) is psychological. It is highly useful both as a coping mechanism and as a treatment of pain: it distracts the patient from the pain and imparts the feeling of having done something to promote one’s own health, including reducing the consumption of medication. The patient’s self-esteem improves.

The most important benefit of exercise in a pain-free range of motion (EPFRM) is psychological. It is highly useful both as a coping mechanism and as a treatment of pain: it distracts the patient from the pain and imparts the feeling of having done something to promote one’s own health, including reducing the consumption of medication. The patient’s self-esteem improves.

Fig. 15.1 Points along the nociceptive pathway of the musculoskeletal system where the EPFRM program exerts its beneficial effects. Exercise increases perfusion and promotes the removal of inflammatory mediators away from the vicinity of the noxious stimulus (1), nociceptors (2) and afferent fibers (3). New patterns of movement quiet the activity of the pathways for nociceptive conduction (4) and nociceptive processing (5) and suppress pain-producing signals. The activation of endorphinergic neurons results in tolerance to pain and diminished pain perception. The ability to cope with pain (5) and pain processing (5) are both improved. Metabolic waste products are transported away from the musculature (6). The concentration of endogenous pain-producing substances is reduced. Better perfusion of the autonomic nervous system (7) (from Krämer and Nentwig 1999).

Which Exercises are Suitable?

Which Exercises are Suitable?

The EPFRM program differs from patient-oriented physiotherapy in three ways: it is not primarily intended to mobilize joints or strengthen muscles, the movements that are used are usually distant from the site of pain, and the purpose is purely that of a dynamic, isotonic exercise program.

The EPFRM program differs from patient-oriented physiotherapy in three ways: it is not primarily intended to mobilize joints or strengthen muscles, the movements that are used are usually distant from the site of pain, and the purpose is purely that of a dynamic, isotonic exercise program.

The EPFRM program is designed simply to promote exercise as such. It uses only dynamic exercises with isotonic muscle contraction in order to stimulate regional and global blood circulation and metabolism, as manifested by a faster pulse, more frequent respirations, and sweating.

In principle, a particular type of exercise can do no harm to the spine or joints if it is carried out with only minimal or no loading of the moving body part and when the joint is smoothly taken through its comfortable range of motion–i.e., without stretching of the joint capsule, torsional movements, or asymmetrical forces. The EPFRM program therefore stresses dynamic, “straight-line” types of exercise such as

swimming

swimming

running

running

cycling.

cycling.

The pattern of movement in these types of exercise is to be contrasted with that of “zig-zag” sports such as tennis, squash, soccer, and volleyball, in which movement is much more often of the stop-and-go variety and puts a greater strain on the joints.

Other types of physical activity besides sports can also be a part of the EPFRM program if they meet the following conditions:

The activity involves dynamic movement with measurable activation of blood circulation and metabolism.

The activity involves dynamic movement with measurable activation of blood circulation and metabolism.

Pain is not increased during the activity or afterward.

Pain is not increased during the activity or afterward.

There is no temporal limit to EPFRM if it is done properly according to these conditions. In other words, a lot of exercise helps a lot.

Exercise Points

Individual types of EPFRM activity have different intensities (Table 15.2). Intensity multiplied by duration yields so-called exercise points. The intensities of the typical kinds of spine- and joint-friendly sports and physical activities in the home, the garden, and the workplace were assessed by pulse measurement and by the associated energy use per 10 min period, and were then assigned point scores. Running and its variants rated highest for intensity. Dynamic garden work (raking, lawn-mowing), physical activity at work, dynamic housework (vacuuming, sweeping, etc.), and leisure-time activities such as dancing or walking/hiking were also assigned points that can be added up over the course of each day and logged by the patient in an “EPFRM diary.”

Stepwise Program

Patients can engage in different types of exercise and sport over the course of the day, depending on their underlying problem and on how they feel. Those who have severe musculoskeletal pain or are still in the rehabilitation phase after disk surgery, trauma, or acute treatment for spinal disorders must limit themselves to level 1 activities (see Table 15.2). As the progress, they can add activities from level 2, after discussion with the treating physician. Before taking up a ball game, for example, the patient can exercise alone with the ball (without an opponent). Tennis begins with long volleys, golf with short games of a few holes.

The intensity of exercise in an EPFRM program normally rises steadily, from a low level just after the acute illness all the way to full capacity. Patients with chronic pain generally stop somewhere along this continuum at an individually appropriate point, usually consisting mainly of level 1 activities.

| ESFR, level 1 | Intensity points |

|---|---|

| Running (jogging) | 10 |

| Walking (hiking) | 3 |

| Swimming | 5 |

| Cycling | 6 |

| Aqua-jogging | 5 |

| Aerobics | 6 |

| Gymnastics | 3 |

| Fitness training | 3 |

| Arm jogging | 4 |

| Dancing | 4 |

| Dynamic gardening | 3 |

| Dynamic housework | 3 |

| Dynamic occupational work | 3 |

| ESFR, level 2 | Intensity points |

| Soccer | 10 |

| Handball | 10 |

| Basketball | 10 |

| Volleyball | 7 |

| Golf | 2 |

| Table tennis | 5 |

| Tennis | 6 |

| Badminton | 8 |

| Squash | 10 |

| Downhill skiing | 4 |

| Cross-country skiing | 10 |

| Mountain climbing | 5 |

| In-line skating | 3 |

| Snowboarding | 4 |

| Water polo | 10 |

EPFRM Units

EPFRM Units

Running

Endurance running, or jogging, scores the largest number of exercise points per unit time, as it is one of the more intense forms of straight-line exercise. When an individual runs with a slightly bent posture and flexed arms, as most people automatically do, the lumbar motion segments are in their central functional position and subject to a regular, rhythmic alternation of mechanical loading and unloading. The same holds for the cervical motion segments as long as the head is bent slightly downward and the gaze is directed downward (Fig. 15.2). An important prerequisite for the beneficial effect of running on the spine is appropriate footwear with well-cushioned soles. All good running shoes on the market today are of this type.

Running is also the ideal form of exercise for individuals with chronic shoulder pain. The dependent arms take mechanical stress off of the subacromial space, and their swinging movements promote circulation in this area.

Running is not a suitable form of exercise for individuals with any sort of disease in the lower limbs, particularly hip, knee, or ankle arthrosis. Nor is it useful for individuals with acute spinal syndromes, as each impact with the ground causes pain. In this situation, the basic concept of “exercise in a pain-free range of motion” is not fulfilled.

Fig. 15.2 Running, an intense form of straight-line exercise, is a particularly suitable sport for patients with chronic back and shoulder pain. Recommended manner of running: mild inclination of the head and trunk, gaze straight ahead and down, short strides.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree