CHAPTER 72 Thoracic Spinal Pain

INTRODUCTION

Disorders of the thoracic spine are as disabling as those in the cervical and lumbar spine and therefore deserve wider recognition than they often receive. As a consequence of having a low incidence, diagnosis and treatment often remain a challenge. Thoracic pain accounts for less than 2% of spinal pain.1 Pain may be due to soft tissue, visceral, disc or structural etiologies.2,3 Pain from thoracic spine lesions may present as pain in the anterior and/or posterior thorax, lumbar spine, and extremities.4 In a study by Acre and Dohramm, 57% were found to present with non-specific pain, 24% present with sensory changes, and 17% present with motor changes.5 The thoracic spine is relatively immobile due to the unique anatomy6 and is stabilized and strengthened by the rib cage.7,8

ETIOLOGY

There are numerous etiologies for thoracic spinal pain as outlined in Table 72.1. One cause of thoracic pain is thoracic disc disease. The incidence of thoracic disc disease is less than 2%.5,9,10 This low incidence may be due to the orientation of the thoracic facet joints in the coronal plane, restraint of the thoracic spine by the ribs and sternum, and the small size of the thoracic discs. Thoracic spine disc herniations account for only 0.2–5% of all disc herniations and have a male predominance. The lower, more mobile segments (T11–12) are affected with greater frequency.5,11–13 The youngest reported case of thoracic disc herniation was in a child 12 years of age.5 Although trauma may contribute to thoracic disc herniation,12 degenerative changes are the most common cause of thoracic disc herniation.5

Table 72.1 Etiology of Thoracic Spine Pain

Most major thoracic disc lesions occur in the lower thoracic spine, but minor thoracic disc lesions occur in the upper and middle regions. Thoracic disc disease usually affects adults in the fourth through sixth decades of life,5,10 in some cases following spinal trauma. The intervertebral discs of the thoracic spine increase in height and width from cranial to caudal. The spinal canal is relatively small, and the epidural space is narrow. The narrowest point is between T4 and T9. The intradiscal pressure is very high in the ventral segment of the thoracic spine, while dorsally the support is mainly by the vertebral joints. Nevertheless, parts of the intervertebral discs can displace towards the spinal canal.14 Seventy percent of these herniations occur in a posterolateral direction. Onset can be acute, subacute, or chronic.10 Ninety percent of patients have signs of spinal cord compression at the time of diagnosis.5

Another cause of thoracic spinal pain is canal stenosis, often stemming from osteoarthritis with facet hypertrophy combined with hypertrophy of the posterior longitudinal ligament and/or ligamentum flavum with or without facet joint hypertrophy.15–17 Thoracic facet joint disease is most common at the T3–5 segment.4 The incidence of thoracic canal stenosis is approximately 2%.18 Infectious causes of thoracic spinal pain include tuberculosis (Pott’s disease), discitis, or osteomyelitis.

This etiology is of particular relevance in the immunocompetent and immunocompromised patient. A retrospective review of 33 patients with tuberculosis of the spine revealed that the majority of the lesions involved the thoracic spine (30%), followed by lumbar spine (27%). Skip lesions were seen in 12% of the patients. Neurological involvement was seen in 50% of patients. The concomitant pulmonary tuberculous rate was 67%.19 In those who are immunocompromised, such as patients with HIV, steroid use, organ transplant, i.v. drug use, or cancer, there may be a delay in diagnosis due to the fact that they may not present with signs and symptoms as evident as in immunocompetent patients.20 Back pain accompanied by fever may be the presenting symptoms of discitis. Septic discitis is inflammation of the intervertebral disc and discovertebral junction. The inflammatory process may extend in to the epidural space, posterior vertebral elements, and paraspinal musculature21 Spondylodiscitis accounts for 2% of all cases of osteomyelitis.22 In a study done by Hopkinson et al., the spectrum of septic discitis was studied. They found that the incidence was 2 per 100 000. Seventy-three percent were 65 years or older; 91% had back pain, with lumbar, thoracic, and then cervical as the most common areas affected. Predisposing factors included cancer, diabetes, and invasive spinal procedures.23

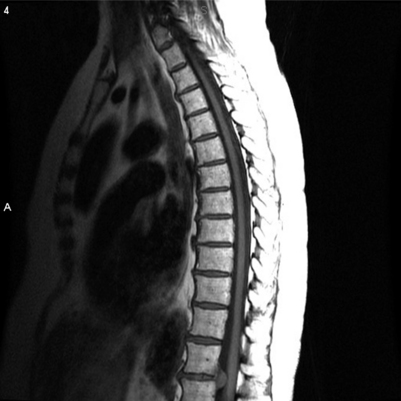

Thoracic spine fractures of various causes may also lead to significant thoracic spinal pain. Thoracic spine fractures are unique due to the anatomy of the thoracic spine and its biomechanics. Fractures can cause neurological compromise because of the small size of the thoracic spinal canal relative to the spinal cord.7,8 Fractures may be due to compression of the vertebral body compounded with or without compression of neural elements as seen in Figure 72.1. Disorders known to contribute to fractures include osteoporosis, tumor such as primary spinal cord lesions, systemic disease such as multiple myeloma, metastatic disease such as those most commonly found from breast, lung, or prostate cancer, or from trauma itself. Not only do the etiologies differ, they may also have varying physical findings, treatments, and functional outcomes.24

Fig. 72.1 Sagittal magnetic resonance image revealing large disc herniation at T11–T12.

(Courtesy of MD Anderson Cancer Center.)

Osteoporosis can lead to significant back pain, kyphosis, impaired respiratory function, and quality of life, as well as morbidity. Fractures due to osteoporosis occur in the spine (especially thoracolumbar), hip, and distal forearm. The lifetime risk of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures is approximately 15% in Caucasian women.25 Vertebral fractures are the most common skeletal injury from osteoporosis, with an incidence of 700 000 per year in the United States.26 Vertebral body height reduction by 20% or 4 mm can be considered a vertebral compression fracture (Fig. 72.2).27 Three types of vertebral fractures in osteoporosis are described: wedge, crush, and biconcave. Most common are wedge fractures (collapsed anterior border with almost intact posterior border), which occur mostly in the midthoracic and thoracolumbar regions.28 In crush fractures, the entire vertebral body is collapsed. Crush fractures are also usually located in the midthoracic or thoracolumbar areas. Biconcave fractures collapse in the central portion of the vertebral body and are more commonly seen in the lumbar region. Those who have wedge fractures tend to experience severe, sharp pain, which usually gradually decreases over 4–8 weeks, although chronic pain is common in this patient group. Patients with superior endplate discontinuity have progression to complete collapse of the vertebral body and have dull, less severe pain. Those with more severe pain initially and a well-defined wedge fracture may have better functional outcomes with pain management and early mobilization.29 Pain due to vertebral fractures is due to a combination of a reduction in body weight, decreased compressive spinal loading, and decreased bone mass.30 Risk factors include lack of hormonal replacement in the perimenopausal period, chronic illnesses, smoking, and alcohol use.31,32

Thoracic-region pain in the adolescent or athlete may be due to muscle strain, stress fractures, or costochondritis. Stress fractures occur when there is overloading of the bone. Common areas of stress fractures include the ribs, especially the first rib. Patients usually complain of pain and shoulder discomfort with radiation into the sternum. Costochondritis is an inflammation (without swelling) and Tietze’s syndrome (with swelling) at the costochondral junction where two different tissue types merge, especially in an area stressed by repetitive movement. Costochondritis usually occurs in ribs two through five and is provoked by movement.33 Scoliosis is another abnormality that may also contribute to thoracic pain. Adult scoliosis usually patterns with more rigid deformity than adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.34

Back pain due to metastatic bone disease can lead to fractures, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord compression, all of which can adversely affect a patient’s functional status and quality of life. Metastatic bone disease leads to increased osteoclastic activity and impaired bone metabolism. Patients with neoplastic diseases such as breast, prostate, or lung cancer, and multiple myeloma may experience some of the sequelae of skeletal complications.35

In rare cases, spinal cord compression may be idiopathic. Saito et al. described a 68-year-old female who had chronic midback pain with slowly progressive weakness over 34 years when she became paraplegic. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed idiopathic spinal cord herniation at T6–7. She underwent T5–8 laminectomy, and her pain improved although she continued to have some lower extremity weakness.36

Post-thoracotomy pain and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) are both causes of thoracic pain of radicular origin. In these cases, the pain referral pattern is neuropathic in nature and not usually due to axial pain.37

Anterior and middle column injuries may contribute to thoracic spinal pain. Posterior column injuries are commonly reported; however, anterior and middle column injuries are often missed and not reported. Katz and Scerpella reviewed seven gymnasts’ reports of back injuries, finding a relatively high incidence of thoracic anterior column pathology in a young patient population. All subjects had tenderness to palpation and were neurologically intact. Two had pain with provocative tests (straight-leg raise or single-leg hyperextension test). Each subject had plain roentgenograms. Three of them were normal. Four subjects had MRIs with findings consistent with disc herniation or degeneration. Of those with abnormal MRI findings, two subjects had vertebral body compression fractures. One subject had a compression fracture of T12 with a 30% loss of height, multiple Schmorl’s nodes, and fractures at L4 and L5. The other one had T11 anterior wedging and T11–12 disc space narrowing. All subjects were treated by physical therapy; two had interventional epidural or facet blocks, and none had surgery. In all cases, practice time was lost. Only one continued to remain competitive. Therefore, anterior and middle column abnormalities from injuries should be included in the differential diagnosis of the thoracic back in athletes.38

Another cause of thoracic back pain may be myofascial pain syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by regional pain, usually in the neck and upper back, with presence of trigger points. The most commonly affected areas of pain and trigger points include the levator scapulae muscles and the upper and lower trapezius.39

Rare causes of thoracic pain may be associated with other pain syndromes such as complex regional pain syndrome-1 (CRPS-1),40 rheumatoid arthritis (RA),41 the T4 syndrome,3 and thoracic nerve root dysfunction (TNRD).42,43 TNRD is most often seen in diabetics who present with chest or abdominal pain, sensory polyneuropathy, or weight loss.42,43 Other causes of TNRD include herpes zoster, scoliosis or osteoarthritis of the thoracic spine, thoracic disc disease, or carcinoma of the thoracic spinal nerve roots.44,45 Rheumatoid arthritis may be associated with thoracic back pain although diffuse joint pain and neck pain may be more prevalent41 The spinal area most commonly affected is the atlantoaxial region; however, thoracic spinal pain may also be present.46 Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) may also be another cause of thoracic back pain. Back pains with sacroiliitis along with other features of spondyloarthropathy (ethesitis and uveitis) are highly suggestive of AS.47

PHYSICAL EXAM

In addition to a thorough history, a general physical exam with a focus on the thoracic spine should be performed. The thorax and back should be examined for any signs of trauma, infection, lesions, or other skin abnormalities. The inspection should also include any overt deformity of the spine such as scoliosis or kyphosis. Abnormalities in posture, biomechanics, and mobility should be noted. The axial spine and ribs should be palpated for any evidence of tenderness. Sensory deficits (hypoesthesia or allodynia) along the back and thorax should be noted. Any abnormalities in the range of motion should be documented. Manual muscle testing in the upper and lower extremities along with reflex testing should be performed.48 The chest should be auscultated to ensure that there are no other physical signs of a systemic disorder. If an infectious etiology is suspected, then examination of lymph nodes and glands may be beneficial. If an inflammatory disease is suspected, then examination of joints and overall musculature is warranted.49 If malignancy is suspected, then the exam should be centered on a systematic approach.

Symptoms of thoracic disc disease may be reported as vague and poorly defined.10,11,50,51 The location of the disc herniation may present with different physical findings. For instance, a central disc herniation may present with pyramidal tract signs, whereas lateral discs may present with radicular pain.6,10–12,52 Common symptoms include motor and sensory deficits with radicular pain or numbness. Bowel and bladder dysfunction may also be present. Examination may reveal upper motor signs such as hyperreflexia, spastic paraparesis, and Babinski signs. If sensory dysfunction is present, it is usually decreased sensation.5,10,12,50,52–54 Symptoms may not present for several years.5,10,12,53 Local pain may be due to distention of the nerve fibers in the anulus fibrosus and posterior longitudinal ligament.10,12 Small disc herniations may also produce spinal cord compression because of the anterior placement of the spinal cord with respect to the thoracic canal.55 Radicular pain may be due to impingement on the short thoracic nerve root by the disc or from traction or stretching of the root by the thecal sac.12

Neurologic symptoms from disorders of the thoracic and lumbar spine can present with upper motor or lower motor findings, cauda equina syndrome, or nerve root lesions.5 In a retrospective review of 26 symptomatic patients, Tokuhashi et al. reviewed different levels of disc herniations and the physical findings for each level. They found that for those with T10–11 and T11–12 disc herniations, the clinical presentation was consistent with upper motor neuron disorders (increased patellar tendon and ankle tendon reflexes), positive Babinski signs, and bowel and bladder dysfunction. In those patients with T12–L1 disc herniations, the physical findings were suggestive of a lower motor neuron disorder (muscle weakness/atrophy, decreased patellar and ankle tendon reflexes, and negative Babinski signs). For the L1–2 disc herniations, mild disorders of cauda equina and sensory disturbance at the anterior or lateral aspect of the thigh were noted. In the L1–3 group, most had severe thigh pain, sensory deficits, and weakness in the quadriceps and tibialis anterior, and decreased or absent patellar tendon reflexes.56

Sometimes, thoracic disc herniations may have unusual presentations or pain referral patterns. Wilke et al. reported a case of thoracic disc herniation that presented with chronic shoulder pain. In this report, a 44-year-old female with shoulder pain underwent acromioplasty. However, symptoms and pain became progressive. She then developed urinary retention. MRI of thoracic spine revealed an extradural space-occupying lesion at T10–11 (sequestered prolapsed intervertebral disc). The patient was treated with costotransversectomy and nucleotomy at T10–11, and her symptoms improved immediately.57

Thoracic disc herniation may also present like acute lumbosacral radiculopathy. Compression of the lumbosacral spinal nerve roots at the lower thoracic level after their exit from the lumbar enlargement may contribute to this physical finding. Lyu et al. reported such a case. A 49-year-old woman was found to have sudden low back pain with radiation into the left buttock and lateral aspect of the left leg and foot. MRI with contrast was consistent with T11–12 midline disc bulge and posterior osteophytes. When she was treated with a laminectomy, her symptoms resolved immediately. A 3-year follow-up revealed normal neurological function with mild low back soreness.58

Thoracic back pain may also present with paresthesias, numbness, or upper extremity pain with or without headaches. DeFranca and Levine described the T4 syndrome where patients presented with upper back stiffness, headaches, and paresthesias without gross neurological deficits. Thoracic joint dysfunction appeared to be the cause of the symptoms.3

For the immunocompromised patient with spinal disease, the most common presenting symptom is back pain (thoracic or lumbar) with radiculopathy, myelopathy, or sensory deficits.20 If discitis is suspected, the patient may have focal back pain, with possible radicular involvement, as well as neurological compromise. The presentation of symptoms may be acute or chronic.21 In the study of septic discitis in the immunocompetent patient by Hopkinson et al., 45 had neurological symptoms such as weakness, urinary retention, diminished reflexes, and sensory deficits. Therefore, focal back pain in a patient with constitutional symptoms and/or neurological sequelae may be indicative of discitis.23 Although many cases of spondylodiscitis may present acutely, some present after years with the disease. In a case report by Finsterer et al., a 65-year-old female had recurrent, localized thoracic back pain for over 2 years. Approximately 9 months after pain onset, she developed sensory deficit of the left lower extremity. Fourteen months prior to admission, she had recurrent fever, mild weakness, and numbness of the lower extremities.59

In patients with osteoporotic vertebral fractures, the spine may appear kyphotic. These patients become shorter as a consequence of vertebral compression and flexed posture. An exaggerated thoracic kyphosis and a protuberant abdomen may compromise and reduce lung capacity.60 Pain is exacerbated by standing erect or with a change of position or movement. Pain may also be reproduced by palpation of the spinous process at the involved level. Neurological deficits are rare, but should be ruled out by a thorough examination of motor and sensory function.61

Patients who have post-thoracotomy pain syndrome have a history of chest and/or spine surgery several weeks or months prior to development of pain. Examination can reveal muscular tenderness, sensitivity to touch, with either decreased or increased sensation. Tenderness is usually along a dermatome near the incision. Upper extremity range of motion may be decreased due to pain.37 Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) may have similar physical findings. Pain is usually unilateral. Pain in PHN is a common presenting symptom. Pain from acute herpes zoster may last a few weeks or persist longer.62 Pain in a dermatomal pattern usually presents 7–10 days prior to the rash. Nerves commonly affected include T4–6, cervical, and trigeminal. Pain is produced by inflammation associated with movement of the virus from sensory nerves to skin and subcutaneous tissues.63 Pain may present in 90% of the patients with allodynia (pain evoked by nonpainful stimuli) or with deafferentation (sensory loss without allodynia).64 Management and treatment should begin immediately after symptoms begin.63

In those patients suspected of having an inflammatory disease such as RA, physical findings in addition to those related to back pain may be beneficial in assisting with the diagnosis. For instance, most patients with RA have symmetrical swelling of small joints and have morning stiffness of at least 1 hour. Extra-articular synovitis along with malaise, fatigue, fever, and weight loss may be seen.41 In patients with AS or suspected AS, there is loss of spinal mobility, especially with restrictions of flexion and extension of the thoracic and lumbar spine, as well as restrictions of chest expansion. Ankylosis along with muscular spasms and limitation of motion may contribute to pain. The spine may be stiff or fused and there may be sacroiliac joint dysfunction along with limitations of bilateral hip involvement, peripheral arthritis, and extra-articular manifestations. Postural abnormalities also contribute to pain. In severe cases, lumbar lordosis is destroyed, the buttocks atrophy, thoracic kyphosis is exaggerated, and the neck is flexed. Thoracic kyphosis may contribute to restricted chest wall motion with concomitant decreased vital capacity.47 If a stress fracture or costochondritis is suspected, patients will experience tenderness with pressure over the affected ribs, especially since the painful area tends to be focal.33

In the myofascial pain syndrome, diagnosis is made by clinical presentation of regional pain, referred pain, taut bands in muscles, tenderness, and restricted range of motion as described by Simons. On examination, pain is due to muscle tension within or over muscles or their attachments. Trigger points are also elicited.65

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree